This week has certainly been not one to remember for US Big Techs and Facebook is the primary responsible, kicking off an unfortunate chain of events. The discovery that Cambridge Analytica - the data company hired by Mr Trump’s campaign - had obtained Facebook data harvested from about 50m people, has raised questions regarding data use and protection of privacy.

But the real question is: how can Facebook data be used to influence a political campaign? The mechanism is simpler than one may think. Back in 2015, Cambridge Analytica gained access to user data provided to a Facebook app called “thisisyourdigitallife”. Beside the data of those that downloaded it (approximately 300,000 people), they were able to extract data from about 50 million by exploiting the list of friends of those who actually used the app. Users were falsely told that the information would be used for academic purposes only. Instead, Cambridge Analytica was accused of using these data to develop personality profiles of users and turn them into targeted ads aimed at influencing the opinions of those that were classified as potentially swing voters.

Even though we cannot estimate for now how successful they were at this (and they still deny influencing any political campaign), this episode gives us an idea of the power of Big Data and of the possible consequences that can derive from its misuse. As far as Facebook’s reaction is concerned, it appears that as soon as they discovered – in 2015 – the use that Cambridge Analytica was making of the data, the requested the company to destroy these same data. Maybe given the importance of the subject, some more verifications should have been made. Or at least they should have notified to the users what was going on and not simply ask forgiveness when everything comes out three years later. This is not for sure the first privacy snafus hitting Facebook.

But is this time going to be different? The signals from Wall Street are clear. Investors have been worrying for some time about the incidence of new regulations on consumer tech platforms, without anything specific to pin their fears to. Now they have it.

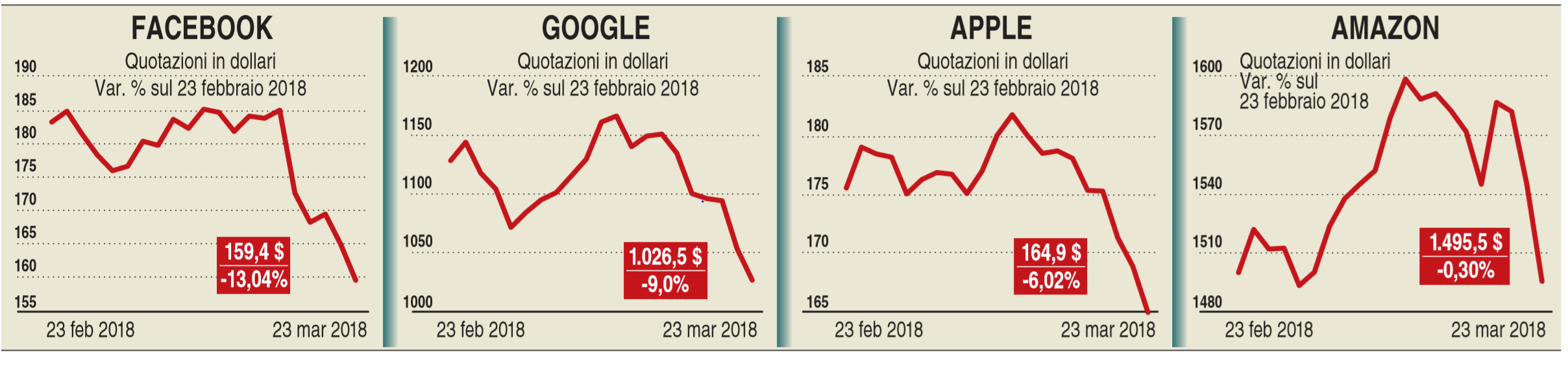

Following the controversy which was firstly announced on Friday 16th, Facebook’s stock price has plummeted by 9% on Monday and Tuesday alone, and kept falling in the following days (despite the little rebound of 0.7% on Wednesday: for sure one of the worst weeks in the company’s history with $60bn wiped off its market value. And this is even more serious if we consider that it adds to an already disappointing performance of Facebook’s stock price in the last month (-13.04% from the 23rd of February). Moreover, it should come as no surprise that the drop of Facebook has had a domino effect on other social media that have a similar business model, like Twitter and partly Google.

But the real question is: how can Facebook data be used to influence a political campaign? The mechanism is simpler than one may think. Back in 2015, Cambridge Analytica gained access to user data provided to a Facebook app called “thisisyourdigitallife”. Beside the data of those that downloaded it (approximately 300,000 people), they were able to extract data from about 50 million by exploiting the list of friends of those who actually used the app. Users were falsely told that the information would be used for academic purposes only. Instead, Cambridge Analytica was accused of using these data to develop personality profiles of users and turn them into targeted ads aimed at influencing the opinions of those that were classified as potentially swing voters.

Even though we cannot estimate for now how successful they were at this (and they still deny influencing any political campaign), this episode gives us an idea of the power of Big Data and of the possible consequences that can derive from its misuse. As far as Facebook’s reaction is concerned, it appears that as soon as they discovered – in 2015 – the use that Cambridge Analytica was making of the data, the requested the company to destroy these same data. Maybe given the importance of the subject, some more verifications should have been made. Or at least they should have notified to the users what was going on and not simply ask forgiveness when everything comes out three years later. This is not for sure the first privacy snafus hitting Facebook.

But is this time going to be different? The signals from Wall Street are clear. Investors have been worrying for some time about the incidence of new regulations on consumer tech platforms, without anything specific to pin their fears to. Now they have it.

Following the controversy which was firstly announced on Friday 16th, Facebook’s stock price has plummeted by 9% on Monday and Tuesday alone, and kept falling in the following days (despite the little rebound of 0.7% on Wednesday: for sure one of the worst weeks in the company’s history with $60bn wiped off its market value. And this is even more serious if we consider that it adds to an already disappointing performance of Facebook’s stock price in the last month (-13.04% from the 23rd of February). Moreover, it should come as no surprise that the drop of Facebook has had a domino effect on other social media that have a similar business model, like Twitter and partly Google.

After 5 days of silence, Mr. Zuckerberg finally spoke with a long post on his profile. He admitted making mistakes and he laid out the company’s plan to improve privacy and said he would testify before politicians — if he was the right person to do so. However, beside this particular case (that made so much noise also for its political significance), the issue of data use and protection remains, and it is burning as never before.

Jeff Chester, executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy, said Mr Zuckerberg’s plan was “insufficient baby steps”. It is Facebook’s business model, not the external app developers which use it, that are the core of its privacy problems, he said, adding that the company should stop working with data brokers to build more detailed profiles and no longer track users across the internet through its audience network. “Facebook needs to engage in a wholesale revision of how it gathers and monetises our information,” he said. That’s precisely the point: in 2014, when most of these data privacy issues were still far ahead, Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, wrote in an open letter:” A few years ago, users of Internet services began to realise that when an online service is free, you're not the customer. You're the product". And data is what you, as a product, can offer. When Zuckerberg speaks of his company purpose with a NPO’s typical vocabulary, like “building communities” and “empowering individuals” and considers the issue as a one-time mistake , he seems unable to concede that their business model depends on monetising the data they collect. There is nothing wrong with this per se, the only condition is that along with the economic benefits of this business strategy, Big Techs accept also the heavy responsibilities stemming from it.

“If you had told me in 2004, when I was just getting started with Facebook, that a big part of my responsibility today would be to help protect the integrity of elections, I wouldn’t really believe it,” Zuckerberg told CNN on Wednesday. There is absolutely no doubt that the idea of Facebook (or the primary embryo of it) that Zuckerberg conceived in 2004 was completely far away from what it is now, nevertheless this is the direct consequence of a business model that they have embraced step by step in the past years.

If Big Techs want their business model to be sustainable, they have to restore trust in their use of data and adopt policies that make a priority of legitimate privacy concerns of users. Governments, on the other hand, have to make sure that this happens. EU in this case breaks new ground. “General Data Protection Regulation” will be in force from May in Europe and it provides that consent to collect and use personal data will have to be specific and unambiguous, not buried in pages of legalese. And it would be desirable that also US regulators follow the example. Only with this joint commitment of Big Techs and regulators can the economic and social benefits of the age of data avoid being suffocated by an appearance of Big Brother-like manipulation that misuse of data (like in this case) can sometimes convey.

Giacomo Longoni

Jeff Chester, executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy, said Mr Zuckerberg’s plan was “insufficient baby steps”. It is Facebook’s business model, not the external app developers which use it, that are the core of its privacy problems, he said, adding that the company should stop working with data brokers to build more detailed profiles and no longer track users across the internet through its audience network. “Facebook needs to engage in a wholesale revision of how it gathers and monetises our information,” he said. That’s precisely the point: in 2014, when most of these data privacy issues were still far ahead, Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, wrote in an open letter:” A few years ago, users of Internet services began to realise that when an online service is free, you're not the customer. You're the product". And data is what you, as a product, can offer. When Zuckerberg speaks of his company purpose with a NPO’s typical vocabulary, like “building communities” and “empowering individuals” and considers the issue as a one-time mistake , he seems unable to concede that their business model depends on monetising the data they collect. There is nothing wrong with this per se, the only condition is that along with the economic benefits of this business strategy, Big Techs accept also the heavy responsibilities stemming from it.

“If you had told me in 2004, when I was just getting started with Facebook, that a big part of my responsibility today would be to help protect the integrity of elections, I wouldn’t really believe it,” Zuckerberg told CNN on Wednesday. There is absolutely no doubt that the idea of Facebook (or the primary embryo of it) that Zuckerberg conceived in 2004 was completely far away from what it is now, nevertheless this is the direct consequence of a business model that they have embraced step by step in the past years.

If Big Techs want their business model to be sustainable, they have to restore trust in their use of data and adopt policies that make a priority of legitimate privacy concerns of users. Governments, on the other hand, have to make sure that this happens. EU in this case breaks new ground. “General Data Protection Regulation” will be in force from May in Europe and it provides that consent to collect and use personal data will have to be specific and unambiguous, not buried in pages of legalese. And it would be desirable that also US regulators follow the example. Only with this joint commitment of Big Techs and regulators can the economic and social benefits of the age of data avoid being suffocated by an appearance of Big Brother-like manipulation that misuse of data (like in this case) can sometimes convey.

Giacomo Longoni