In the past couple of months, we have seen Central Banks from all over the world assume a more dovish tone, with a series of quantitative easing policies and cuts in interest rates, in an attempt to revert the threat of a global economic slowdown.

This has been the story for the Fed (Federal Reserve), which has cut rates for the first time since the financial crisis, and the ECB (European Central Bank), which has established negative interest rates for nothing less than the first time in history. It has also been the case for several other countries’ Central Banks, such as Mexico (25bps cut, the first since 2014), Hong Kong (25bps cut, the first since 2008), Dominican Republic, Russia, Chile, Peru, Turkey, India and many others.

As one could imagine, Brazil’s Central Bank, presided by Roberto Campos Neto (appointed by the country’s newly elected president, Jair Bolsonaro), was no exception to the rule, with three 50bps cuts in 2019, lowering rates (called “Selic rates”) from 6.50% to 5.00% (in nominal terms). Investors are pricing even more cuts in the next year, with real interest rates expected to drop to almost 0% in 2020.

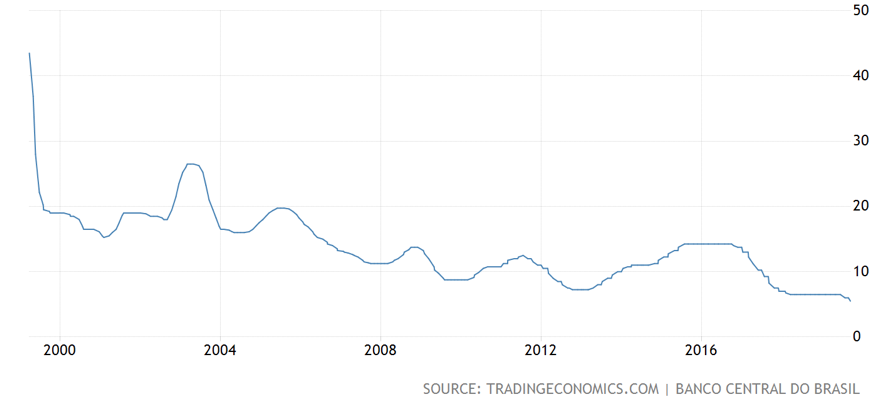

These two recent cuts have put Brazilian interest rates at its all-time-low, thanks to the easing movement started in 2016, where Illan Goldfajn, former president of the Brazilian Central Bank, pushed interest rates from a 14% area to the previously seen 6.50%, as we can see from the chart below:

This has been the story for the Fed (Federal Reserve), which has cut rates for the first time since the financial crisis, and the ECB (European Central Bank), which has established negative interest rates for nothing less than the first time in history. It has also been the case for several other countries’ Central Banks, such as Mexico (25bps cut, the first since 2014), Hong Kong (25bps cut, the first since 2008), Dominican Republic, Russia, Chile, Peru, Turkey, India and many others.

As one could imagine, Brazil’s Central Bank, presided by Roberto Campos Neto (appointed by the country’s newly elected president, Jair Bolsonaro), was no exception to the rule, with three 50bps cuts in 2019, lowering rates (called “Selic rates”) from 6.50% to 5.00% (in nominal terms). Investors are pricing even more cuts in the next year, with real interest rates expected to drop to almost 0% in 2020.

These two recent cuts have put Brazilian interest rates at its all-time-low, thanks to the easing movement started in 2016, where Illan Goldfajn, former president of the Brazilian Central Bank, pushed interest rates from a 14% area to the previously seen 6.50%, as we can see from the chart below:

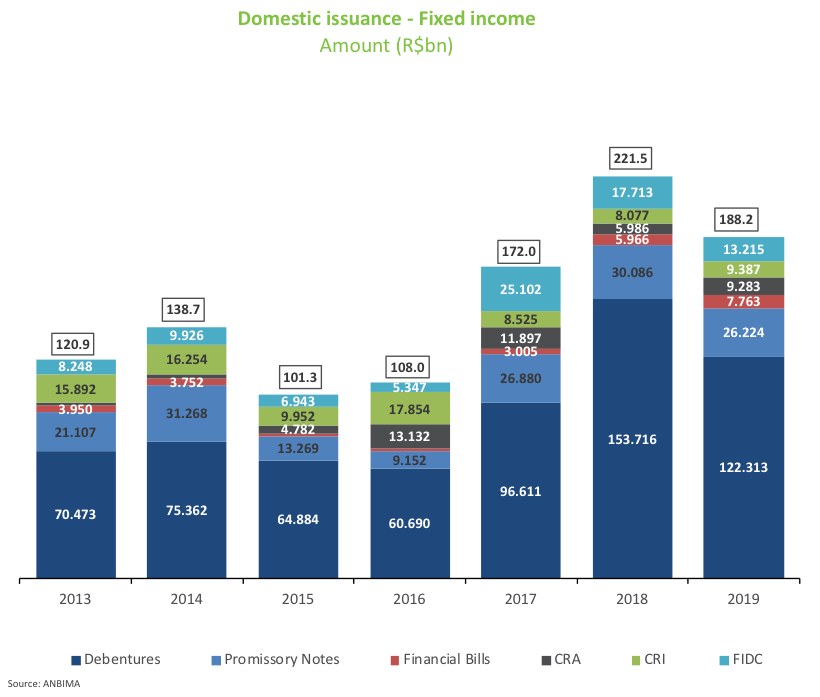

With historically low interest rates, the debt space in Brazil has experienced a substantial growth in the last years, going from a total issued amount of R$120.9bn in 2013FY to R$221.5bn in 2018FY and an expected of R$251bn in 2019FY[1], which represents a CAGR of 12.9% for the 2013-2018 period.

Concomitantly, we have seen significant growth in liquidity in the market, with fixed income funds growing to a total of R$2,042bn[2] in AUM by the end of 2018, with a 12.8% CAGR in the 2013-2018 period. Below we can see the growth in nominal terms for all of Brazil’s main debt instruments.

Concomitantly, we have seen significant growth in liquidity in the market, with fixed income funds growing to a total of R$2,042bn[2] in AUM by the end of 2018, with a 12.8% CAGR in the 2013-2018 period. Below we can see the growth in nominal terms for all of Brazil’s main debt instruments.

In this new (and unprecedented) environment of low-interest rates and booming local capital markets, banks, companies, and investors now find themselves faced with the need to adapt their modus operandi to make the most out of this new situation. The task of this article is, precisely, to attempt to describe these players are adapting to these “newly enacted” rules of Brazilian DCM. Well, let’s start by talking about the easiest one: banks.

As in most countries in the world, in Brazil there are mainly two types of investment banks: local (mainly Itaú BBA, Bradesco, Santander[3] and Banco do Brasil) and foreign (J.P. Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, etc.). On the one hand, local banks are present in both international and domestic debt-related transactions, due to their extensive relationship with local companies and their vast distribution capacity in local markets. Foreign banks, on the other hand, are mostly included in offshore transactions, usually bond issuances or Liability Management exercises, due to their global presence and extremely competent Syndicate platform, capable of global-scale distribution of securities.

Until the last couple of years, it was common for foreign banks to focus most of their time and energy on offshore transactions, making their “big bucks” out of them. That made sense because local transactions were much harder to be included in (due to restricted local distribution capacity of foreign banks and fierce competition by local ones), paid less (due to their fees being BRL-denominated), and represented more workforce (due to Brazil’s heavy-handed regulation: transactions in Brazilian markets take, from conception to execution, from one to three months on average, whereas offshore transactions can take as little as three days).

However, with the boom in local DCM, it has become rarer for companies to tap offshore markets, which is pushing foreign banks to put more effort into local transactions, finding alternative solutions in which they could be helpful, especially in terms of expertise in execution.

This brings us to the second component in our equation: companies. With lower interest rates, it has become particularly attractive for some companies to put forward domestic issuances, even if they have the size to issue abroad. This has been the case for many players, such as Petrobras (O&G State-owned company), Cielo (Leader in the payments sector in Brazil), CBA (a subsidiary of “Grupo Votorantim” focused on aluminum) and a number of others, who have issued local debt and used the proceeds to perform Liability Management exercises offshore, in an effort to exchange their outstanding USD-denominated debt to BRL.

However, this is not the only effect this new environment has on companies. The second and maybe the strangest one is the number of debut issuers tapping the markets in the last couple of months. These issuers are usually companies with revenues below R$400mm, who were used to getting funds from bilateral deals with banks, due to Capital Markets lack of interest in such small (usually R$50mm, versus an average of R$200-300mm) and risky deals (usually local deals are carried out by companies AA or AAA-rated in local scale, whereas these small companies are, in most cases, not even rated).

This takes us to the third and final part of our analysis. If these debut issuers are succeeding in issuing debt securities and selling them to the markets, someone must be buying them. And that’s where investors come to the scene. With interest rates at their lowest, fixed income investors are now turning their eyes to credits they had never paid much attention to, in an attempt to raise the yields generated by their portfolios. In this scenario, they hand-pick projects they believe in (usually after extensive analysis, personal visits to the company, and other measures) and, more than anything else, that provide valuable collateral in case of default (such as real-estate properties).

One recent case that reflects these new market conditions is the recent issuance of a R$35mm CRI (the Brazilian equivalent to an MBS) by Pernambuco Construtura, a real estate company that focuses its operations on the northeast of the country, more specifically in the state of Pernambuco, with total revenues of R$180mm in 2018. The money raised by the company was used entirely to fund two new projects, and the debt pays a floating rate of CDI (Brazilian interbank offered rate) +5.00% (equivalent to almost 200% of the CDI), with a tenor of 4 years. All of the R$35mm were distributed to one investor, a high-yield real-estate-focused fund called RBR, who actually visited the state of Pernambuco and inspected the land in which the projects would be done, as well as the structure of the project and its management. RBR fund managers have reported that they are looking for more deals such as this one, taking special care to only enter deals with solid guarantees, considered by the fund as even more important than the company default risk.

Therefore, we can see that all market participants are striving to adapt their modus operandi to this low-interest rate environment. On the banks’ side, more time is being spent trying to increase revenues from local deals. On the big companies’ side, a large portion of USD-denominated debt is being exchanged to BRL-denominated liability. On the small companies’ hand, capital markets have recently become attractive. And, finally, investors are more prone to taking risks, picking high-yield deals in which to invest and raise the return of their portfolios.

Joao Paulo Parizotto

As in most countries in the world, in Brazil there are mainly two types of investment banks: local (mainly Itaú BBA, Bradesco, Santander[3] and Banco do Brasil) and foreign (J.P. Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, etc.). On the one hand, local banks are present in both international and domestic debt-related transactions, due to their extensive relationship with local companies and their vast distribution capacity in local markets. Foreign banks, on the other hand, are mostly included in offshore transactions, usually bond issuances or Liability Management exercises, due to their global presence and extremely competent Syndicate platform, capable of global-scale distribution of securities.

Until the last couple of years, it was common for foreign banks to focus most of their time and energy on offshore transactions, making their “big bucks” out of them. That made sense because local transactions were much harder to be included in (due to restricted local distribution capacity of foreign banks and fierce competition by local ones), paid less (due to their fees being BRL-denominated), and represented more workforce (due to Brazil’s heavy-handed regulation: transactions in Brazilian markets take, from conception to execution, from one to three months on average, whereas offshore transactions can take as little as three days).

However, with the boom in local DCM, it has become rarer for companies to tap offshore markets, which is pushing foreign banks to put more effort into local transactions, finding alternative solutions in which they could be helpful, especially in terms of expertise in execution.

This brings us to the second component in our equation: companies. With lower interest rates, it has become particularly attractive for some companies to put forward domestic issuances, even if they have the size to issue abroad. This has been the case for many players, such as Petrobras (O&G State-owned company), Cielo (Leader in the payments sector in Brazil), CBA (a subsidiary of “Grupo Votorantim” focused on aluminum) and a number of others, who have issued local debt and used the proceeds to perform Liability Management exercises offshore, in an effort to exchange their outstanding USD-denominated debt to BRL.

However, this is not the only effect this new environment has on companies. The second and maybe the strangest one is the number of debut issuers tapping the markets in the last couple of months. These issuers are usually companies with revenues below R$400mm, who were used to getting funds from bilateral deals with banks, due to Capital Markets lack of interest in such small (usually R$50mm, versus an average of R$200-300mm) and risky deals (usually local deals are carried out by companies AA or AAA-rated in local scale, whereas these small companies are, in most cases, not even rated).

This takes us to the third and final part of our analysis. If these debut issuers are succeeding in issuing debt securities and selling them to the markets, someone must be buying them. And that’s where investors come to the scene. With interest rates at their lowest, fixed income investors are now turning their eyes to credits they had never paid much attention to, in an attempt to raise the yields generated by their portfolios. In this scenario, they hand-pick projects they believe in (usually after extensive analysis, personal visits to the company, and other measures) and, more than anything else, that provide valuable collateral in case of default (such as real-estate properties).

One recent case that reflects these new market conditions is the recent issuance of a R$35mm CRI (the Brazilian equivalent to an MBS) by Pernambuco Construtura, a real estate company that focuses its operations on the northeast of the country, more specifically in the state of Pernambuco, with total revenues of R$180mm in 2018. The money raised by the company was used entirely to fund two new projects, and the debt pays a floating rate of CDI (Brazilian interbank offered rate) +5.00% (equivalent to almost 200% of the CDI), with a tenor of 4 years. All of the R$35mm were distributed to one investor, a high-yield real-estate-focused fund called RBR, who actually visited the state of Pernambuco and inspected the land in which the projects would be done, as well as the structure of the project and its management. RBR fund managers have reported that they are looking for more deals such as this one, taking special care to only enter deals with solid guarantees, considered by the fund as even more important than the company default risk.

Therefore, we can see that all market participants are striving to adapt their modus operandi to this low-interest rate environment. On the banks’ side, more time is being spent trying to increase revenues from local deals. On the big companies’ side, a large portion of USD-denominated debt is being exchanged to BRL-denominated liability. On the small companies’ hand, capital markets have recently become attractive. And, finally, investors are more prone to taking risks, picking high-yield deals in which to invest and raise the return of their portfolios.

Joao Paulo Parizotto