Overview

South Korea’s economy is fourth in Asia and tenth in the world by nominal GDP. Having experienced an extraordinary economic growth since the Korean War, the state is now one of the most developed on the planet, with a high-performance education system, an export-oriented approach and unusual resilience to macroeconomic stress, as shown by an IMF report back in 2010.

The assessment, based on debt, government spending and fiscal reserves, remains relevant, as the country navigated the Coronavirus pandemic much better than other nations.

Perhaps most notably, South Korea is one of the only two highly developed countries that did not experience a recession following the 2008 crisis, the other one being Australia.

GDP

Ranking fourth in Asia behind China, Japan and India, the country had a GDP of approximately $1.63T in 2020 and $1.66T in 2021. Manufacturing is by far the largest part of national output, contributing with more than double the output compared to the second-highest category, accommodation and food service activities.

Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and mining are the sectors contributing the least to the GDP, in line with the country’s primary objective of industrialisation and modernisation following the Korean War.

South Korea mostly imports commodities and exports high tech equipment. Manufacturing plays an important role, even in the COVID economy; however, because most production is exported and currently there is great economic uncertainty around the world, this sector is not expected to fuel the post-pandemic recovery.

The state’s economy relies heavily on exports to China. Liquidity problems, recent Coronavirus outbreaks and supply chain stress may affect the trade between the two countries, adding downward pressure on the Korean economy. The Korean Development Institute, indeed, underlines “modest growth”.

Exports rose approximately 20% year-on-year in February, pushed by the semiconductor industry and by petrochemicals. Investments in facilities and constructions rose below 7% year-on-year, and momentum depends heavily on interest rate decisions.

Fiscality, monetary issues and financial markets

According to the Korean Development Institute, the state needs to slow down its stimulus programs and gradually adjust its fiscal policy to contain the ballooning public debt. While monetary policy normalisation is desirable, the Institute noted that a rise in short-term interest rates may negatively impact consumer spending; this is due to the fact that the country is predicted to rely mostly on its service sector and its population’s high willingness to spend as the pandemic begins downsizing. Korea Treasury yields have gone up over 68 basis points over the last 6 months, incorporating inflation expectations.

Inflation in March 2022 was 4.1%, up from 3.7% in February, with core inflation at 3.3%. So far, it has been outpacing the predictions of an average of 3% throughout the year of 2022. Compared to other major Asian economies, such as China, Japan and Indonesia, the inflation rate was considerably higher, but lower than India’s 6.95%.

The board of the Bank of Korea has decided on a total increase of 75 basis points from the beginning of the pandemic. While data showed investors did not expect a rate increase in April, the Bank decided to raise by 25 basis points, up to 1.5%. Further increases are expected, as the now-retired governor announced at the beginning of the year, but they need fine-tuning to ensure they do not become a disincentive for spending and investment.

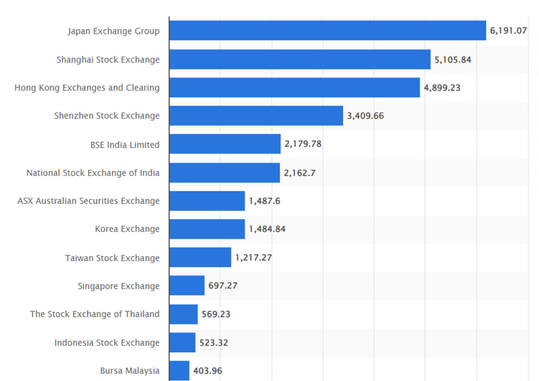

In 2019, South Korea had the 8th largest financial market by total capitalisation in the Asia-Pacific region.

South Korea’s economy is fourth in Asia and tenth in the world by nominal GDP. Having experienced an extraordinary economic growth since the Korean War, the state is now one of the most developed on the planet, with a high-performance education system, an export-oriented approach and unusual resilience to macroeconomic stress, as shown by an IMF report back in 2010.

The assessment, based on debt, government spending and fiscal reserves, remains relevant, as the country navigated the Coronavirus pandemic much better than other nations.

Perhaps most notably, South Korea is one of the only two highly developed countries that did not experience a recession following the 2008 crisis, the other one being Australia.

GDP

Ranking fourth in Asia behind China, Japan and India, the country had a GDP of approximately $1.63T in 2020 and $1.66T in 2021. Manufacturing is by far the largest part of national output, contributing with more than double the output compared to the second-highest category, accommodation and food service activities.

Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and mining are the sectors contributing the least to the GDP, in line with the country’s primary objective of industrialisation and modernisation following the Korean War.

South Korea mostly imports commodities and exports high tech equipment. Manufacturing plays an important role, even in the COVID economy; however, because most production is exported and currently there is great economic uncertainty around the world, this sector is not expected to fuel the post-pandemic recovery.

The state’s economy relies heavily on exports to China. Liquidity problems, recent Coronavirus outbreaks and supply chain stress may affect the trade between the two countries, adding downward pressure on the Korean economy. The Korean Development Institute, indeed, underlines “modest growth”.

Exports rose approximately 20% year-on-year in February, pushed by the semiconductor industry and by petrochemicals. Investments in facilities and constructions rose below 7% year-on-year, and momentum depends heavily on interest rate decisions.

Fiscality, monetary issues and financial markets

According to the Korean Development Institute, the state needs to slow down its stimulus programs and gradually adjust its fiscal policy to contain the ballooning public debt. While monetary policy normalisation is desirable, the Institute noted that a rise in short-term interest rates may negatively impact consumer spending; this is due to the fact that the country is predicted to rely mostly on its service sector and its population’s high willingness to spend as the pandemic begins downsizing. Korea Treasury yields have gone up over 68 basis points over the last 6 months, incorporating inflation expectations.

Inflation in March 2022 was 4.1%, up from 3.7% in February, with core inflation at 3.3%. So far, it has been outpacing the predictions of an average of 3% throughout the year of 2022. Compared to other major Asian economies, such as China, Japan and Indonesia, the inflation rate was considerably higher, but lower than India’s 6.95%.

The board of the Bank of Korea has decided on a total increase of 75 basis points from the beginning of the pandemic. While data showed investors did not expect a rate increase in April, the Bank decided to raise by 25 basis points, up to 1.5%. Further increases are expected, as the now-retired governor announced at the beginning of the year, but they need fine-tuning to ensure they do not become a disincentive for spending and investment.

In 2019, South Korea had the 8th largest financial market by total capitalisation in the Asia-Pacific region.

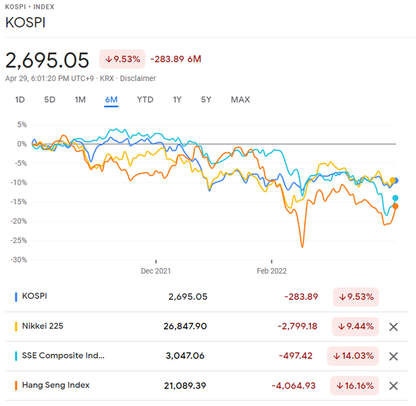

KOSPI is the main index tracking South Korea’s performance.

Its evolution over the last six months has been largely aligned with that of other major exchanges, on account of some common dynamic factors in the region, including China’s manufacturing problems in the context of the most recent lockdowns, sanctions on Russia and the economy of the US. The major Asian economies are also highly linked through trade.

Population and labor market

The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was at record-low of 2.7% in March and April 2022, reflecting a highly resilient labor market.

Nevertheless, alarmingly for its long-term economic outlook, South Korea has a crucial population problem. In the context of a rapidly declining birth rate, the total population fell year-on-year, for the first time ever, in 2020. In the same year, the total fertility rate in the country was the lowest in the world, at approximately 0.84 b/w. Enamoured with the idea of the “small and prosperous family”, the South Korean government began a family planning campaign in 1962, aimed at reducing “unwanted births”. In the context of aggressive economic growth, TFR fell from over 6 to approximately 4.5 in just 8 years, and reached 1.6 in the 1990s. In 2002, the country’s National Pension Institute highlighted the major risk of the pension funds running out of money, due to the extremely high ratio of retirees to the working population.

This has major implications for the country’s ability to sustain its position as an economic power in the future.

Main industries and sectors in South Korea

Over the years, the industrial sector has consistently contributed to the nation's GDP, employing roughly one-fourth of the workforce.

Manufacturing has been the engine of economic success within the industry, which includes manufacturing, mining, construction, electricity, water and gas as subsectors. Manufacturing has been the engine of economic progress within the industry, notably during the 1980s.

Apart from manufacturing, mining activity has been steadily increasing in recent years, albeit it is still limited to a few metals and minerals. South Korea produces steel, zinc, copper, gold, iron ore, lead, magnesite, barite, silver, and tungsten, but local resources are insufficient to meet industrial demand. To fill the void, South Korea must import mineral commodities.

Because the Korean Peninsula offers a diverse spectrum of minerals, the majority of mineral deposits are in North Korea, with a few mineral deposits in South Korea.

Korea has risen to become a major worldwide producer of cadmium, slab zinc, and steel, as well as a major regional producer of refined copper, pyrophyllite, cement, zeolites, and talc, since 2010. While there are rivals ahead of the country, South Korea's mining sector still has some well-developed and technologically advanced enterprises, both private and public, ensuring the government's active engagement in mining.

POSCO, a major mining firm, got an agreement with the South Korean government in 2010 to begin extracting lithium from seawater. In addition, the government cooperated with POSCO to spend $26 million in the construction of a lithium extraction facility, which has been operational since 2014. Meanwhile, when its ancient iron ore mine was renovated in 2010, another mining firm, KORES, aimed to find rare earth elements in Korean soil. Since then, exploratory operations to examine the rare element concentration in different mining locations around the nation have been performed.

Hyundai Steel, LS-Nikko Copper, Dongkuk Steel, State-owned Korea Zinc, Poongsan Corp, and Pohang Iron and Steel Company are among the firms in South Korea's mining industry that are technologically advanced and well-developed (POSCO). Because of the high demand for metals in the local market, the country imports the majority of its metal requirements.

Electronics, autos, telecommunications, shipbuilding, chemicals, and steel are the most important sectors. With globally recognised businesses like Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. and Hynix Semiconductor, the country is one of the major producers of electronic goods and semiconductors.

In particular, the automotive sector is one of the world's largest. South Korea used to be solely involved in the assembly of parts imported from other countries, but it is now one of the world's main automobile manufacturing nations. The country's yearly output was 1.01 million units in 1988. During the 1990s, the country produced a wide range of in-house models with distinct performance, design, and technical characteristics.

Why is there such a large valuation discount?

Despite South Korea’s great achievements in terms of GDP growth, the South Korean stock market might be one of the cheapest in the world. We believe that the main reasons for this discount are the generally weak corporate governance policies employed by South Korean companies and the inefficient capital allocation by management teams.

Historically, majority shareholders and the management of South Korean companies have employed strategies that work against the benefit of all shareholders. Through circular holdings and pyramid-like structures, majority shareholders of certain business groups, known as “chaebols”, were able to control networks of public companies despite owning relatively low personal stakes. These controlling shareholders often siphoned off company assets for their own benefit through related-party transactions or unfair mergers.

Compounding the issue, capital return to shareholders has been extremely low as majority shareholders tended to view company money as their own. Moreover, South Korean managements’ understanding of efficient capital allocation has been rudimentary, as they grapple with the current low-growth environment after a few decades of high growth. Many South Korean companies sit on large piles of cash and idle assets, further lowering their return on equity.

Because of the high inefficiency and extremely short-term nature of the South Korean stock market, we believe the South Korean market provides opportunities to purchase growing world-class assets at attractive absolute and relative valuations, in what looks to be the late stages of the current long-term debt and economic cycle. The key is to identify quality businesses run by families and/or management teams who are placing increased importance on the need to align themselves with minority shareholders. By identifying and investing in these opportunities, we believe investors could generate attractive risk-adjusted idiosyncratic returns in a turbulent market.

Risks

With respect to geo-political risks, we believe that the most noteworthy is the relation with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. Although the probability of South Korea's involvement in a large-scale conflict with the DPRK is to be considered remote, tensions with its North Korean neighbour undoubtedly constitute the greatest risk factor in terms of security and consequently in economic terms. Critical issues could arise in relation to the continuation of the North Korean missile and nuclear program, and territorial disputes occur along the maritime boundary line in the East and West between the two Koreas. This is due to the establishment of a maritime demarcation line (Northern Limit Line) that is not fully recognised by Pyongyang, a circumstance that sometimes generates tensions between navies. Furthermore, another dispute regards sovereignty of the Dokdo/Takeshima islands, cause of repeated tensions in recent years in the Japanese-Korean relations.

With respect to economic risks instead, the most noteworthy are the high level of private indebtedness, weakness of SMEs, and possible financial instability on international markets.

With an equivalent public debt of around 40% of GDP, South Korea expresses the lowest value among OECD countries. In the face of this extremely positive data, especially if compared to that of the European and Japanese economies, South Korea features a remarkably high level of private debt (89.2% of GDP) with an average ratio of private debt to disposable income above 160%. This component may lead to substantial systemic risks in a possible phase of persistent low growth and/or deflationary dynamics of the real estate market.

Korean SMEs are often financially fragile due to low capitalisation and high debt rates. In a situation of greater volatility of the exchange rate of the national currency compared to the past, and decreasing access to credit, many companies run the risk of going in suffering. A prolonged stressful situation for this sector, in the absence of adequate interventions on the credit side, could determine many insolvency situations that could have important repercussions on the national economy.

Lastly, the divergence of monetary policies could lead to financial instability at international level. The United States is expected to revise interest rates upwards in the coming months. South Korea, due to an ample current account surplus and substantial foreign currency reserves, should be protected. However, the possible negative effects on the export markets of Korea and the possible increase in interest rates might slow the country's growth.

Sources

Bank for International Settlements

Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System

Bloomberg

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Dalton Investments

Google Finance

IHS Markit

Info Mercati Esteri

International Monetary Fund

Korea Development Institute

Population Reference Bureau

Reuters

Statista

The World Bank

Trading Economics

Written by Teodor Matei, Lorenzo Morosini and Angela Sofia Siciliano

The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was at record-low of 2.7% in March and April 2022, reflecting a highly resilient labor market.

Nevertheless, alarmingly for its long-term economic outlook, South Korea has a crucial population problem. In the context of a rapidly declining birth rate, the total population fell year-on-year, for the first time ever, in 2020. In the same year, the total fertility rate in the country was the lowest in the world, at approximately 0.84 b/w. Enamoured with the idea of the “small and prosperous family”, the South Korean government began a family planning campaign in 1962, aimed at reducing “unwanted births”. In the context of aggressive economic growth, TFR fell from over 6 to approximately 4.5 in just 8 years, and reached 1.6 in the 1990s. In 2002, the country’s National Pension Institute highlighted the major risk of the pension funds running out of money, due to the extremely high ratio of retirees to the working population.

This has major implications for the country’s ability to sustain its position as an economic power in the future.

Main industries and sectors in South Korea

Over the years, the industrial sector has consistently contributed to the nation's GDP, employing roughly one-fourth of the workforce.

Manufacturing has been the engine of economic success within the industry, which includes manufacturing, mining, construction, electricity, water and gas as subsectors. Manufacturing has been the engine of economic progress within the industry, notably during the 1980s.

Apart from manufacturing, mining activity has been steadily increasing in recent years, albeit it is still limited to a few metals and minerals. South Korea produces steel, zinc, copper, gold, iron ore, lead, magnesite, barite, silver, and tungsten, but local resources are insufficient to meet industrial demand. To fill the void, South Korea must import mineral commodities.

Because the Korean Peninsula offers a diverse spectrum of minerals, the majority of mineral deposits are in North Korea, with a few mineral deposits in South Korea.

Korea has risen to become a major worldwide producer of cadmium, slab zinc, and steel, as well as a major regional producer of refined copper, pyrophyllite, cement, zeolites, and talc, since 2010. While there are rivals ahead of the country, South Korea's mining sector still has some well-developed and technologically advanced enterprises, both private and public, ensuring the government's active engagement in mining.

POSCO, a major mining firm, got an agreement with the South Korean government in 2010 to begin extracting lithium from seawater. In addition, the government cooperated with POSCO to spend $26 million in the construction of a lithium extraction facility, which has been operational since 2014. Meanwhile, when its ancient iron ore mine was renovated in 2010, another mining firm, KORES, aimed to find rare earth elements in Korean soil. Since then, exploratory operations to examine the rare element concentration in different mining locations around the nation have been performed.

Hyundai Steel, LS-Nikko Copper, Dongkuk Steel, State-owned Korea Zinc, Poongsan Corp, and Pohang Iron and Steel Company are among the firms in South Korea's mining industry that are technologically advanced and well-developed (POSCO). Because of the high demand for metals in the local market, the country imports the majority of its metal requirements.

Electronics, autos, telecommunications, shipbuilding, chemicals, and steel are the most important sectors. With globally recognised businesses like Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. and Hynix Semiconductor, the country is one of the major producers of electronic goods and semiconductors.

In particular, the automotive sector is one of the world's largest. South Korea used to be solely involved in the assembly of parts imported from other countries, but it is now one of the world's main automobile manufacturing nations. The country's yearly output was 1.01 million units in 1988. During the 1990s, the country produced a wide range of in-house models with distinct performance, design, and technical characteristics.

Why is there such a large valuation discount?

Despite South Korea’s great achievements in terms of GDP growth, the South Korean stock market might be one of the cheapest in the world. We believe that the main reasons for this discount are the generally weak corporate governance policies employed by South Korean companies and the inefficient capital allocation by management teams.

Historically, majority shareholders and the management of South Korean companies have employed strategies that work against the benefit of all shareholders. Through circular holdings and pyramid-like structures, majority shareholders of certain business groups, known as “chaebols”, were able to control networks of public companies despite owning relatively low personal stakes. These controlling shareholders often siphoned off company assets for their own benefit through related-party transactions or unfair mergers.

Compounding the issue, capital return to shareholders has been extremely low as majority shareholders tended to view company money as their own. Moreover, South Korean managements’ understanding of efficient capital allocation has been rudimentary, as they grapple with the current low-growth environment after a few decades of high growth. Many South Korean companies sit on large piles of cash and idle assets, further lowering their return on equity.

Because of the high inefficiency and extremely short-term nature of the South Korean stock market, we believe the South Korean market provides opportunities to purchase growing world-class assets at attractive absolute and relative valuations, in what looks to be the late stages of the current long-term debt and economic cycle. The key is to identify quality businesses run by families and/or management teams who are placing increased importance on the need to align themselves with minority shareholders. By identifying and investing in these opportunities, we believe investors could generate attractive risk-adjusted idiosyncratic returns in a turbulent market.

Risks

With respect to geo-political risks, we believe that the most noteworthy is the relation with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. Although the probability of South Korea's involvement in a large-scale conflict with the DPRK is to be considered remote, tensions with its North Korean neighbour undoubtedly constitute the greatest risk factor in terms of security and consequently in economic terms. Critical issues could arise in relation to the continuation of the North Korean missile and nuclear program, and territorial disputes occur along the maritime boundary line in the East and West between the two Koreas. This is due to the establishment of a maritime demarcation line (Northern Limit Line) that is not fully recognised by Pyongyang, a circumstance that sometimes generates tensions between navies. Furthermore, another dispute regards sovereignty of the Dokdo/Takeshima islands, cause of repeated tensions in recent years in the Japanese-Korean relations.

With respect to economic risks instead, the most noteworthy are the high level of private indebtedness, weakness of SMEs, and possible financial instability on international markets.

With an equivalent public debt of around 40% of GDP, South Korea expresses the lowest value among OECD countries. In the face of this extremely positive data, especially if compared to that of the European and Japanese economies, South Korea features a remarkably high level of private debt (89.2% of GDP) with an average ratio of private debt to disposable income above 160%. This component may lead to substantial systemic risks in a possible phase of persistent low growth and/or deflationary dynamics of the real estate market.

Korean SMEs are often financially fragile due to low capitalisation and high debt rates. In a situation of greater volatility of the exchange rate of the national currency compared to the past, and decreasing access to credit, many companies run the risk of going in suffering. A prolonged stressful situation for this sector, in the absence of adequate interventions on the credit side, could determine many insolvency situations that could have important repercussions on the national economy.

Lastly, the divergence of monetary policies could lead to financial instability at international level. The United States is expected to revise interest rates upwards in the coming months. South Korea, due to an ample current account surplus and substantial foreign currency reserves, should be protected. However, the possible negative effects on the export markets of Korea and the possible increase in interest rates might slow the country's growth.

Sources

Bank for International Settlements

Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System

Bloomberg

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Dalton Investments

Google Finance

IHS Markit

Info Mercati Esteri

International Monetary Fund

Korea Development Institute

Population Reference Bureau

Reuters

Statista

The World Bank

Trading Economics

Written by Teodor Matei, Lorenzo Morosini and Angela Sofia Siciliano