Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors, previously considered optional supplementary information, are progressively becoming a driver to a company’s bottom line and potential investors. Even though the U.S. is withdrawing from the Paris Climate Agreement, U.S. companies will still need to regulate and improve their ESG ratings as sustainability becomes increasingly more important to the global investor pool.

Harvard Business Review surveyed 70 senior executives from 43 different institutional investors, including large asset holders (such as CalPERS, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System), the public pension funds of Sweden, Japan, and the Netherlands, and the 3 largest asset managers globally (Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street). The research discovered that ESG was consistently a top priority for these executives, and senior leaders were regularly engaged with ESG initiatives. However, research by Bank of America Merrill Lynch found that many U.S. corporate managers underestimate the prevalence of ESG. These executives estimated that 5% of their shares are owned by investors with sustainable investment plans, but in reality the proportion is closer to 25%.

Furthermore, many investors are even willing to forgo some returns to support sustainable investing. According to a study by NN Investment Partners, investors were willing to sacrifice 2.4% per year to invest in ESG and other funds with a positive impact. Investors are seeing increasingly more value in long-term preparedness, questioning before investing whether a company’s business model will be able to transition toward the sustainable, low-carbon economy of the future and maneuver growing climate regulation.

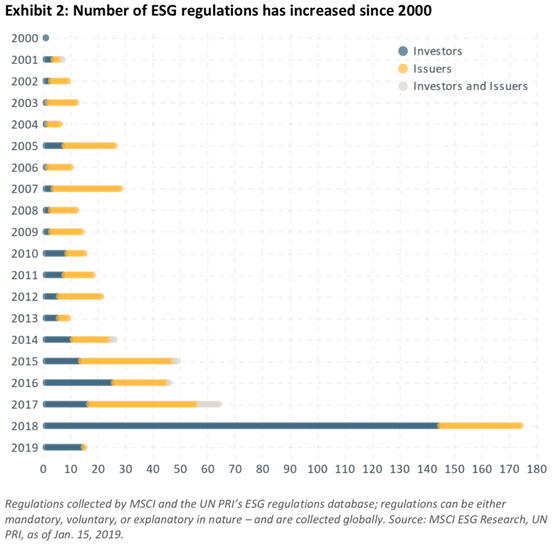

Following this trend, the number of regulations concerning ESG has grown exponentially, with more proposed in 2018 alone than in the six years prior. Past regulation mostly targeted issuers, but as can be seen in the graph below, 80% of the new regulations in 2018 referred to institutional investors instead. It is yet to be seen whether investors will support these regulations as vigorously as those imposed on issuers, although many of these measures are meant to clarify the abilities and duties of investors. Specifically for institutions and large asset owners, these regulations seek to lessen the uncertainty around how ESG should be considered in these companies’ investment processes.

Harvard Business Review surveyed 70 senior executives from 43 different institutional investors, including large asset holders (such as CalPERS, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System), the public pension funds of Sweden, Japan, and the Netherlands, and the 3 largest asset managers globally (Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street). The research discovered that ESG was consistently a top priority for these executives, and senior leaders were regularly engaged with ESG initiatives. However, research by Bank of America Merrill Lynch found that many U.S. corporate managers underestimate the prevalence of ESG. These executives estimated that 5% of their shares are owned by investors with sustainable investment plans, but in reality the proportion is closer to 25%.

Furthermore, many investors are even willing to forgo some returns to support sustainable investing. According to a study by NN Investment Partners, investors were willing to sacrifice 2.4% per year to invest in ESG and other funds with a positive impact. Investors are seeing increasingly more value in long-term preparedness, questioning before investing whether a company’s business model will be able to transition toward the sustainable, low-carbon economy of the future and maneuver growing climate regulation.

Following this trend, the number of regulations concerning ESG has grown exponentially, with more proposed in 2018 alone than in the six years prior. Past regulation mostly targeted issuers, but as can be seen in the graph below, 80% of the new regulations in 2018 referred to institutional investors instead. It is yet to be seen whether investors will support these regulations as vigorously as those imposed on issuers, although many of these measures are meant to clarify the abilities and duties of investors. Specifically for institutions and large asset owners, these regulations seek to lessen the uncertainty around how ESG should be considered in these companies’ investment processes.

As investors’ interest in ESG grows, it’s imperative that disclosures and terminology are standardized to avoid “greenwashing”—investors need to be clearly informed on whether a company actually has sustainable practices or simply empty language. Unfortunately, in the US, regulation has been largely hindered by the partisan divide over climate change. The Department of Labor under President Obama passed regulation that was meant to help sustainable investments be offered as options for retirement plans. Under President Trump, some of these measures have been weakened and there has been less regulatory activity in general. Policies from 2018 were less supportive of using ESG factors during the investment-selection process, but some Congressmen floated bills to enable retirement plans to offer certain sustainable investments. As asset management only becomes more global, having consistent ESG regulation will decrease the costs and increase the efficacy of sustainable investment products regardless of where investors reside.

Then, from the company perspective, there is regulation needed to lessen carbon emissions. Two month ago, on September 23, was the UN Climate Action Summit, the largest high-level climate meeting since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. This time, the heads of state were told to leave the flowery speeches at home and actually build tangible plans to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. After investment data provider Arabesque S-Ray found that over 80% of the world’s largest companies will not meet the original Paris Agreement’s target (to limit rising temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2050), activists and economists agreed that current policies are too gentle to force large corporations to make substantial changes. Tougher rhetoric is underway; for companies that do not report their carbon emissions at all, data providers such as Arabesque S-Ray could automatically assign them a 3°C increase in their reports to investors.

French president Emmanuel Macron stated that France would not conduct new trade with countries that are not part of the Paris Climate Agreement, and that imports with negative environmental impacts should be avoided or compensated for. Other countries proposed carbon taxes or emissions trading schemes, while activists condemned some initiatives as mere greenwashing exercises. Ultimately, however, increasing regulation will begin forcing companies to reduce their carbon footprint, hopefully sooner rather than later. Honda, for instance, has recently announced the largest clean-power purchase made by an automaker, consisting of 320 megawatts of wind- and solar-powered electricity. Other automakers and carbon-intensive industries will eventually follow suit to remain competitive, although primarily in countries that pledged stricter targets at the UN Summit.

Even in the U.S., where the Paris Agreement has been rebuffed and the fundamental existence of climate change has been questioned, investors are increasingly asking about the environmental impacts of the companies in their portfolios. If data providers start using harsher measurements for companies that don’t report carbon data, more companies will begin measuring their emissions to avoid losing investors, especially investors in more progressive countries. Unfortunately, this improvement will likely only happen in industries that already have small carbon footprints, such as financials or technology. In the meantime, unless more revolutionary policies come to light from the Climate Summit, there isn’t enough regulation to substantially incentivize carbon-intensive industries to incur additional costs to save a seemingly distant future. Perhaps investors’ interest in ESG is our best hope.

Then, from the company perspective, there is regulation needed to lessen carbon emissions. Two month ago, on September 23, was the UN Climate Action Summit, the largest high-level climate meeting since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. This time, the heads of state were told to leave the flowery speeches at home and actually build tangible plans to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. After investment data provider Arabesque S-Ray found that over 80% of the world’s largest companies will not meet the original Paris Agreement’s target (to limit rising temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2050), activists and economists agreed that current policies are too gentle to force large corporations to make substantial changes. Tougher rhetoric is underway; for companies that do not report their carbon emissions at all, data providers such as Arabesque S-Ray could automatically assign them a 3°C increase in their reports to investors.

French president Emmanuel Macron stated that France would not conduct new trade with countries that are not part of the Paris Climate Agreement, and that imports with negative environmental impacts should be avoided or compensated for. Other countries proposed carbon taxes or emissions trading schemes, while activists condemned some initiatives as mere greenwashing exercises. Ultimately, however, increasing regulation will begin forcing companies to reduce their carbon footprint, hopefully sooner rather than later. Honda, for instance, has recently announced the largest clean-power purchase made by an automaker, consisting of 320 megawatts of wind- and solar-powered electricity. Other automakers and carbon-intensive industries will eventually follow suit to remain competitive, although primarily in countries that pledged stricter targets at the UN Summit.

Even in the U.S., where the Paris Agreement has been rebuffed and the fundamental existence of climate change has been questioned, investors are increasingly asking about the environmental impacts of the companies in their portfolios. If data providers start using harsher measurements for companies that don’t report carbon data, more companies will begin measuring their emissions to avoid losing investors, especially investors in more progressive countries. Unfortunately, this improvement will likely only happen in industries that already have small carbon footprints, such as financials or technology. In the meantime, unless more revolutionary policies come to light from the Climate Summit, there isn’t enough regulation to substantially incentivize carbon-intensive industries to incur additional costs to save a seemingly distant future. Perhaps investors’ interest in ESG is our best hope.

Kristiana Santos - 22/11/2019