Increasing fears of Japan-style economic prospects are arising in Europe. Indeed, some similarities between the Japanese economic evolution and the Eurozone’s are becoming straightforward and more realistic. However, Eurozone distinguishes itself from Japan by different aspects, making the comparison less obvious and thus temper the possible parallels that can be drawn between Japanese economic situation and European economic forecasts.

The Japanese economic situation: a faltering domestic economy.

Three decades from now, Japan has entered a long-lasting period of low growth, low inflation and an aging population. Today, the Japanese economy is still struggling, and records a growth of only 0.1 per cent in the third quarter of this year. To counteract, this critical economic situation, Abe, the prime minister of Japan, has actively implemented one main policy, named « Abenomics » since December 2012. It relies on deficit spending and massive quantitative easing through huge purchases of government bonds for the purpose of solving the Japanese economic stagnation.

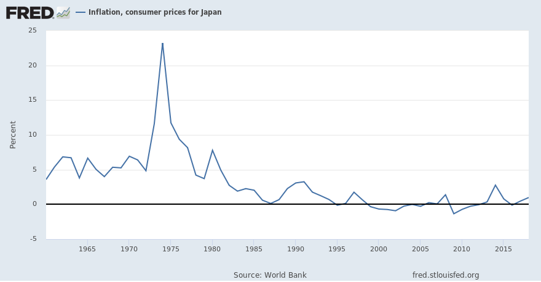

However, even though Japan interest rate has been lowered to -0.1 per cent since 2016, the Bank of Japan has failed to reach and maintain its 2 per cent inflation target; the current rate is just 0.2 per cent and the economy remains flat. A negative growth for the final quarter of 2019 is even expected after the consumption tax rate was increased to 10 per cent in October with the aim of answering the budgetary costs of rising health and welfare costs of a dwindling and aging population. Indeed, Japan's population is among the world’s fastest declining and aging population. The working-age population fell from 80.6 million in 2012 to 76 million in 2017, rising the urgency to postpone the retirement age and bring more women into the workforce.

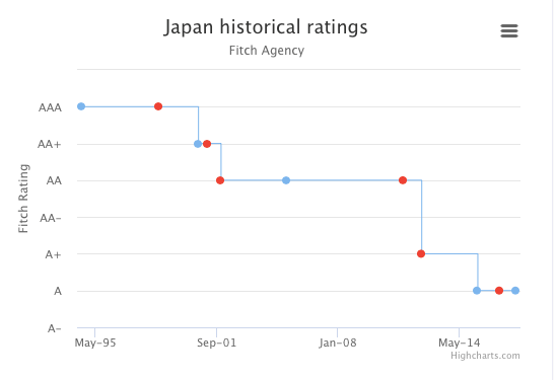

These demographic facts are not a good omen for the Abenomics’ goals of reinstating Japan as a competitive and productive country, but rather increase the emergency for stopping the massive government debt’s growth. Actually, it is worth noting that Japan is the world’s most indebted country with a government debt level that has ran up over the past three decades, rising from 65 per cent of GDP in 1991 to more than 240 in 2019. Fitch’s rating of Japan declined from triple A rating in 1998, to an expected rate around A nowadays.

Nevertheless, even though Japan is facing a long-lasting faltering economy, this A outlook for Japan’s rating is expected to be stable according to Fitch. Indeed, this rating reflects not only the low growth prospect and the high debt level of Japan, but also its healthiness and power as an advanced economy, with both strong governance and strong public organization. The strength of Japan’s yen, considered as a safe haven currency relies on the fact that much of Japan’s wealth is held overseas, in foreign assets and currencies. Hence, the yen can be repatriated whenever facing a crisis, boosting its demand and restoring its strength.

The Japanese economic situation: a faltering domestic economy.

Three decades from now, Japan has entered a long-lasting period of low growth, low inflation and an aging population. Today, the Japanese economy is still struggling, and records a growth of only 0.1 per cent in the third quarter of this year. To counteract, this critical economic situation, Abe, the prime minister of Japan, has actively implemented one main policy, named « Abenomics » since December 2012. It relies on deficit spending and massive quantitative easing through huge purchases of government bonds for the purpose of solving the Japanese economic stagnation.

However, even though Japan interest rate has been lowered to -0.1 per cent since 2016, the Bank of Japan has failed to reach and maintain its 2 per cent inflation target; the current rate is just 0.2 per cent and the economy remains flat. A negative growth for the final quarter of 2019 is even expected after the consumption tax rate was increased to 10 per cent in October with the aim of answering the budgetary costs of rising health and welfare costs of a dwindling and aging population. Indeed, Japan's population is among the world’s fastest declining and aging population. The working-age population fell from 80.6 million in 2012 to 76 million in 2017, rising the urgency to postpone the retirement age and bring more women into the workforce.

These demographic facts are not a good omen for the Abenomics’ goals of reinstating Japan as a competitive and productive country, but rather increase the emergency for stopping the massive government debt’s growth. Actually, it is worth noting that Japan is the world’s most indebted country with a government debt level that has ran up over the past three decades, rising from 65 per cent of GDP in 1991 to more than 240 in 2019. Fitch’s rating of Japan declined from triple A rating in 1998, to an expected rate around A nowadays.

Nevertheless, even though Japan is facing a long-lasting faltering economy, this A outlook for Japan’s rating is expected to be stable according to Fitch. Indeed, this rating reflects not only the low growth prospect and the high debt level of Japan, but also its healthiness and power as an advanced economy, with both strong governance and strong public organization. The strength of Japan’s yen, considered as a safe haven currency relies on the fact that much of Japan’s wealth is held overseas, in foreign assets and currencies. Hence, the yen can be repatriated whenever facing a crisis, boosting its demand and restoring its strength.

The Eurozone: showing strong similarities with Japan

For some years now, this trend that Japan has followed since the 1990s - high public debt ratio, low and even negative inflation and growth rates - has also been dawning in the eurozone. Actually, the Greek sovereign debt ratio which rose to 183% after the European financial crisis, the Spanish deflationary period between 2014 and 2016, and the Italian negative growth rate between 2008 and 2013 reflect similarities with Japan economic situation.

The causes that have led to this critical situation in Japan also seem to have appeared in the eurozone. Especially, both the unprofitable loans, bonds and corporate debt, and a relatively deregulated financial market in the 1990s have generated a bubble in the market and which busted and led to a substantial financial crisis in Japan. Similarly, a bursting bubble in the financial markets has affected the whole world and the eurozone in 2008. Moreover, the European Central Bank’s huge bond-buying program has similarities with the Bank of Japan’s quantitative easing measures.

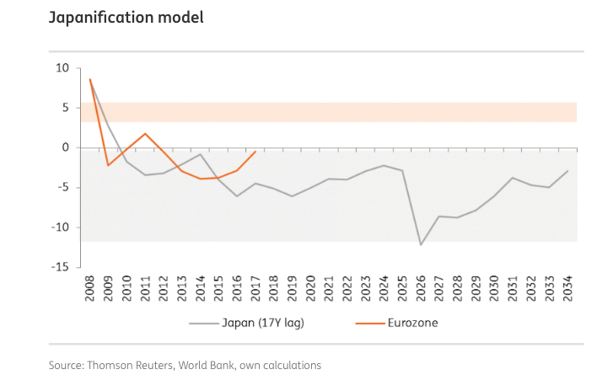

In order to evaluate this striking resemblance between Japan and the Eurozone, ING developed a model to observe the evolution trends of countries taking into account their economic growth, their inflation level, their demographic change and the central bank's interest rate. The similarities between 1990s Japan and today’s Europe are clear. Indeed, the study of the Japanese trends from 1992, date at which we estimate the beginning of its current crisis, and the comparison with the eurozone’s evolutions since 2009, when the financial troubles has been triggered, show evident similarities.

However, the Eurozone’s economic situation differentiates itself from the Japanese case in diverse aspects, thus allowing to aspire for a better economic conjunction.

Actually, the Euro area debt level is far from being as important as the Japanese one. The eurozone recorded a government debt equivalent to 87.90 percent of the country's Gross Domestic Product in 2018, almost three times less than the debt to GDP ratio of Japan.

Moreover, while Japan has been facing some deflationary periods, the Euro Area has not met any inflation rate under the zero rate.

The difficulty with this comparison also resides in the wide inhomogeneities that exist in the eurozone. Southern Europe, such as Italy and Greece, differs greatly from the north and has, to some extent, questionably performed far worse than Japan. We should note that this lack of homogeneity with wide variations among EU states economic performance could moreover constraint and limit the power of the ECB to intervene on the markets as the BoJ is doing and to implement efficient policies to respond to this Japanification of the eurozone. For instance, the ECB would struggle to replicate the BoJ’s interventions on financial markets with same magnitude, due to the institutional and political strains the ECB is bearing regarding its bond-buying operations. Indeed, to ensure that the ECB’s sovereign risk is enough diversified, the ECB is constrained on its bond buying and cannot purchase more than 33 percent of a country's debt.

Even though it could be argued that these fundamental differences between the Eurozone and Japan - such as the inhomogeneity among its member states economic situations, the fiscal and monetary policy constraints, and the strains on political cohesion - make the comparison between Japan and the eurozone less meaningful, might instead make it more difficult for the eurozone to implement efficient policies to boost economic growth and reach inflation target and thus to avoid Japanification.

Clémence Louzier