What sounds weird about a deal in which the Italian company Recordati gets acquired by CVC? Or about HIG Capital investing in the Italian real estate? A few more examples could clarify the situation: The Carlyle Group recently decided to bet on Italian interior design companies such as Flos; Permira has, on the other hand, acquired La Piadineria in a €250+ million deal. If you still cannot spot anything odd, follow my excursus on the Italian private equity industry.

Recently, PE funds have grown exponentially all over the world. They are currently able to raise money at the fastest rate since the 2008 crisis, thanks to the low-interest-rates era we are in. “Private equity has matured as an industry after the crisis with more competition for a limited number of deals,” said Brenda Rainey, a senior practice director at Bain & Company. As the number of funds in the markets increased, the competition has become increasingly fierce, resulting in a trim of high-return deals: nowadays, less than 20% of buyouts (compared to around 35-40% just before the crisis) yield more than 5x the initial investment, as an analysis by Cambridge Associates and Bain & Company showed.

This could make us think that the private equity industry is overcrowded, and it may seem there are no more possibilities of growth, or further development for this alternative way of investing. However, several players are unceasingly joining the PE party (eager to gain a slice of the cake), and Q1 2018 showed a 4% surge of operations worldwide with respect to the same period of the previous year, and an impressive 35% increase in the funds raised in Europe, where roughly 8,000 funds invested almost €92bn in circa 64,000 portfolio companies.

Italy represents a fertile ground for the evolution of the private equity industry, which is still relatively small, compared to the GDP and the SMEs-based economic structure. A PE fund typically invests in the equity of a non-public company, and the elements in favor of its Italian development are the high need of equity, where there are severe issues connected to the banking industry, the undercapitalization of companies and their necessity of growing and investing in order to be successful in gradually more competitive and global markets.

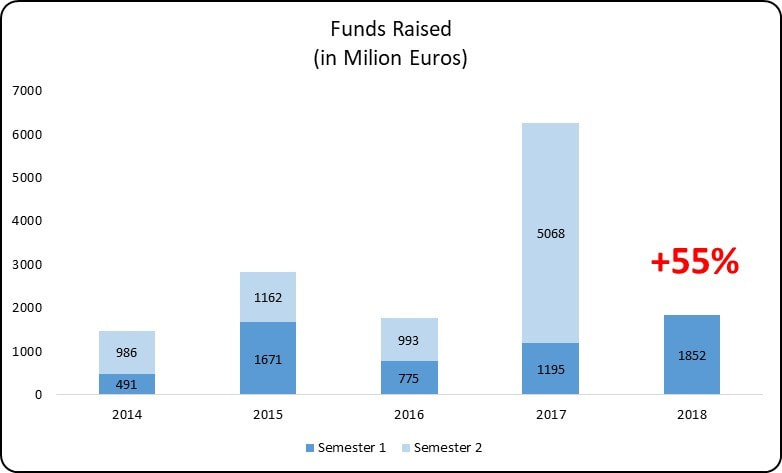

By analyzing the last report made by AIFI (the Italian association of Private Equity, Venture Capital and Private Debt) the scenario may seem encouraging, since it shows that there are a lot of possibilities for this industry to grow. In 2017, funds raised were more than €6bn, up 265% with respect 2016. This trend is surviving in 2018 as well, since, in the first semester, the equity collected amounted to almost €2bn, 55% more than in the first six months of the previous year.

Recently, PE funds have grown exponentially all over the world. They are currently able to raise money at the fastest rate since the 2008 crisis, thanks to the low-interest-rates era we are in. “Private equity has matured as an industry after the crisis with more competition for a limited number of deals,” said Brenda Rainey, a senior practice director at Bain & Company. As the number of funds in the markets increased, the competition has become increasingly fierce, resulting in a trim of high-return deals: nowadays, less than 20% of buyouts (compared to around 35-40% just before the crisis) yield more than 5x the initial investment, as an analysis by Cambridge Associates and Bain & Company showed.

This could make us think that the private equity industry is overcrowded, and it may seem there are no more possibilities of growth, or further development for this alternative way of investing. However, several players are unceasingly joining the PE party (eager to gain a slice of the cake), and Q1 2018 showed a 4% surge of operations worldwide with respect to the same period of the previous year, and an impressive 35% increase in the funds raised in Europe, where roughly 8,000 funds invested almost €92bn in circa 64,000 portfolio companies.

Italy represents a fertile ground for the evolution of the private equity industry, which is still relatively small, compared to the GDP and the SMEs-based economic structure. A PE fund typically invests in the equity of a non-public company, and the elements in favor of its Italian development are the high need of equity, where there are severe issues connected to the banking industry, the undercapitalization of companies and their necessity of growing and investing in order to be successful in gradually more competitive and global markets.

By analyzing the last report made by AIFI (the Italian association of Private Equity, Venture Capital and Private Debt) the scenario may seem encouraging, since it shows that there are a lot of possibilities for this industry to grow. In 2017, funds raised were more than €6bn, up 265% with respect 2016. This trend is surviving in 2018 as well, since, in the first semester, the equity collected amounted to almost €2bn, 55% more than in the first six months of the previous year.

A question is raised: why Italy is not an overcrowded party for PE funds, but rather an emerging trend? What’s wrong with Italy?

Some experts blame the excessive financial leverage used for private equity deals (an average buyout is financed by debt for roughly 70% of the overall investment). If a high debt-to-equity ratio is badly structured, it could create negative consequences for portfolio companies, as their capital structure is immediately built upon the acquired company. However, this kind of activity represents just a portion of a PE fund’s activity and the financial leverage, especially in Italy, has always been used, primarily by entrepreneurs. Researches even demonstrate that private entrepreneurs use financial leverage for their own companies more aggressively and in a riskier manner than PE funds do. In addition, structuring a company with much more debt than equity is a smart way to boost its growth, e.g. through acquisitions, or to carry out a generational change, e.g. thanks to management buyouts or family buyouts.

Another critique and possible explanation is directed towards the instruments used by PE firms to carry out their activities: closed funds in most cases. A rigidity in the investment and disinvestment periods, limited liquidity, complex techniques of fees calculation and the fund closeness itself are meaningful downsides.

The result is the necessity of new investment instruments, more flexible and balanced, less speculative, more adherent to industrial and strategic needs of portfolio companies and less illiquid, always with the goal of identifying companies, investing and helping them to enhance the overall enterprise value.

Equilibrium and flexibility are the key drivers that made so that the funds raised more equity and the number of deals closed increased steadily over the last few years in Italy. Nevertheless, it’s necessary to analyze more deeply the afore-mentioned values. Last semester, it has been possible to have a massive rise in the funds raised mainly thanks to foreign investors (primarily insurance companies and pension funds), who account for about half of the funds raised and desire to exploit the fact that the PE industry is not so competitive as in the rest of the world, seeking, therefore, huge returns on investments. Even more importantly, it’s crucial to stress that in Italy almost 50% of deals are closed by foreign funds, abler to adapt to the Italian economic structure and attracted by the numerous family businesses (around 85% of all Italian companies). HIG, CVC, Permira, Catterton, Carlyle and Ardian are among the most important foreign PE firms that bet on Italian SMEs and contribute to high volumes of buyouts.

At this stage, the alarm should ring: what’s strange about the deals introduced eat the very beginning? The Italian PE industry is growing at a fast rate, but the alarming situation is that it’s just thanks to American, English or French funds and foreign investors who smell the presence of “easy money” and low competition, which allows them to gain higher-than-usual returns.

Overall, Italy is lagging as far as the private equity industry is concerned. It is a country with an economic organization interesting for the private equity goal of value creation and simply a new area where fund managers want to invest in order to escape the fierce competition they must face elsewhere, which is reducing the returns on investment. Italian big funds have just disappeared (e.g. BS and Investitori Associati, and Clessidra will soon join the club of “retired” PE funds according to experts) and the smallest ones try to survive working on smaller deals (they focus on small-medium buyouts), on average, but the credit for the boost of this alternative investment in Italy must be given to foreigners.

The trend we are witnessing is even more shocking if we think to ethics consequences, i.e. a buyout ultimately changes the owner of a company, which directly goes in the hands of the investor. Only foreigners seem to appreciate “made in Italy” products and put effort and money in order to gain control over them, while Italians just give them for granted and let them slip off their hands, or simply have no longer the strength to retain ownership.

Francesco Baggini

Some experts blame the excessive financial leverage used for private equity deals (an average buyout is financed by debt for roughly 70% of the overall investment). If a high debt-to-equity ratio is badly structured, it could create negative consequences for portfolio companies, as their capital structure is immediately built upon the acquired company. However, this kind of activity represents just a portion of a PE fund’s activity and the financial leverage, especially in Italy, has always been used, primarily by entrepreneurs. Researches even demonstrate that private entrepreneurs use financial leverage for their own companies more aggressively and in a riskier manner than PE funds do. In addition, structuring a company with much more debt than equity is a smart way to boost its growth, e.g. through acquisitions, or to carry out a generational change, e.g. thanks to management buyouts or family buyouts.

Another critique and possible explanation is directed towards the instruments used by PE firms to carry out their activities: closed funds in most cases. A rigidity in the investment and disinvestment periods, limited liquidity, complex techniques of fees calculation and the fund closeness itself are meaningful downsides.

The result is the necessity of new investment instruments, more flexible and balanced, less speculative, more adherent to industrial and strategic needs of portfolio companies and less illiquid, always with the goal of identifying companies, investing and helping them to enhance the overall enterprise value.

Equilibrium and flexibility are the key drivers that made so that the funds raised more equity and the number of deals closed increased steadily over the last few years in Italy. Nevertheless, it’s necessary to analyze more deeply the afore-mentioned values. Last semester, it has been possible to have a massive rise in the funds raised mainly thanks to foreign investors (primarily insurance companies and pension funds), who account for about half of the funds raised and desire to exploit the fact that the PE industry is not so competitive as in the rest of the world, seeking, therefore, huge returns on investments. Even more importantly, it’s crucial to stress that in Italy almost 50% of deals are closed by foreign funds, abler to adapt to the Italian economic structure and attracted by the numerous family businesses (around 85% of all Italian companies). HIG, CVC, Permira, Catterton, Carlyle and Ardian are among the most important foreign PE firms that bet on Italian SMEs and contribute to high volumes of buyouts.

At this stage, the alarm should ring: what’s strange about the deals introduced eat the very beginning? The Italian PE industry is growing at a fast rate, but the alarming situation is that it’s just thanks to American, English or French funds and foreign investors who smell the presence of “easy money” and low competition, which allows them to gain higher-than-usual returns.

Overall, Italy is lagging as far as the private equity industry is concerned. It is a country with an economic organization interesting for the private equity goal of value creation and simply a new area where fund managers want to invest in order to escape the fierce competition they must face elsewhere, which is reducing the returns on investment. Italian big funds have just disappeared (e.g. BS and Investitori Associati, and Clessidra will soon join the club of “retired” PE funds according to experts) and the smallest ones try to survive working on smaller deals (they focus on small-medium buyouts), on average, but the credit for the boost of this alternative investment in Italy must be given to foreigners.

The trend we are witnessing is even more shocking if we think to ethics consequences, i.e. a buyout ultimately changes the owner of a company, which directly goes in the hands of the investor. Only foreigners seem to appreciate “made in Italy” products and put effort and money in order to gain control over them, while Italians just give them for granted and let them slip off their hands, or simply have no longer the strength to retain ownership.

Francesco Baggini