During the last few weeks, we have been increasingly hearing about Japanese Yield Curve Control and the “big move from 0.25 to 0.50”. But what is yield curve control? How has it been implemented in Japan and what is changing now? In the following article we will analyze these issues and provide insights about what might happen next.

Technically, what is Yield Curve Control?

The yield curve, a graphical representation of the yields on bonds of varying maturities issued by a government or corporation, is an essential tool for investors and policymakers as it provides valuable insights into the health of the economy. It shows the relationship between interest rates and maturities and its shape and slope (typically upward sloping, with longer-term bonds often higher yields than shorter-term bonds) can portray the market's expectations for future economic growth and interest rates.

Traditionally, central banks target policy rates as a primary tool to conduct monetary intervention, as movements in these rates are thought to influence longer-term yields. When the central bank raises policy rates, short-term bond yields tend to increase, causing the yield curve to flatten or invert. The supply and demand for bonds of various maturities also impact the yield curve. When demand for long-term bonds increases, their prices rise, causing yields to decline and the yield curve to flatten. Moreover, investors' expectations of future inflation and economic growth can influence the yield curve's shape. When inflation is expected to rise, long-term bond yields increase, causing the yield curve to steepen.

Yield curve control (YCC) is a monetary policy tool used by central banks to manage interest rates in the economy. It basically consists in the central bank setting a target for a specific yield on government bonds with a certain maturity date, typically long-term, and then buying bonds on the open market or directly intervening in the bond market to ensure that the market yield stays at or near that target level. The central bank doesn't take any action if bond yields of targeted maturities stay below this ceiling. However, if prices go up above this price floor, the central bank intervenes by purchasing targeted-maturity bonds to increase demand and so the price of these bonds, allowing to lower yields below the ceiling (given the inversely proportional relation).

Governments employ YCC for various reasons, with the primary motive being to bolster the economy during times of turmoil. Take the COVID-19 pandemic for instance: central banks worldwide resorted to YCC policies to stabilize financial markets and provide aid to the economy. With low and steady interest rates, YCC can offset the adverse economic impacts of a crisis and lend a sense of stability and predictability to the market. In addition, governments use YCC to support specific policy objectives, such as boosting inflation or fostering economic growth. For example, the Bank of Japan has employed YCC to try to achieve a predetermined inflation rate in the economy, whereas the Federal Reserve has used it to boost the economic recovery post the financial crisis.

As seen above, the purpose of YCC is to maintain lower interest rates and boost overall economic activity. This happens through two main channels. Firstly, lower interest rates imply lower cost of debt, which ultimately leads to an increase in borrowing that is directed to an increase in consumption and/or in investments. Secondly, lower interest rates also boost asset prices leading to an overall increase in wealth thus allowing more consumer spending. In addition, YCC can help to reduce volatility in the economy by anchoring inflation expectations, therefore making it easier for businesses and individuals to plan for the future. This might be very important for central banks that have struggled with low inflation in recent years as YCC can help ensure that inflation expectations do not fall too far below the central bank's target level.

Unfortunately, YCC also has its limitations. One potential issue is that it may compromise the transparency of the central bank's decision-making process. When the central bank intervenes in the bond market to regulate interest rates, it can be challenging for market players to understand the central bank's actual intentions and anticipate its future actions. This can increase market instability and render it more difficult for investors to make informed choices. Furthermore, YCC may distort market signals and produce unintended outcomes. For example, when the central bank sets a specific interest rate target, investors may excessively concentrate on that target and not consider other important market signals. This can lead to improper allocation of capital and potentially create bubbles in specific asset classes.

The use of YCC has become increasingly popular among central banks around the world, particularly in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. In the United States, the Federal Reserve has experimented with YCC in recent years, while the Bank of Japan has been using the tool since 2016.

The yield curve, a graphical representation of the yields on bonds of varying maturities issued by a government or corporation, is an essential tool for investors and policymakers as it provides valuable insights into the health of the economy. It shows the relationship between interest rates and maturities and its shape and slope (typically upward sloping, with longer-term bonds often higher yields than shorter-term bonds) can portray the market's expectations for future economic growth and interest rates.

Traditionally, central banks target policy rates as a primary tool to conduct monetary intervention, as movements in these rates are thought to influence longer-term yields. When the central bank raises policy rates, short-term bond yields tend to increase, causing the yield curve to flatten or invert. The supply and demand for bonds of various maturities also impact the yield curve. When demand for long-term bonds increases, their prices rise, causing yields to decline and the yield curve to flatten. Moreover, investors' expectations of future inflation and economic growth can influence the yield curve's shape. When inflation is expected to rise, long-term bond yields increase, causing the yield curve to steepen.

Yield curve control (YCC) is a monetary policy tool used by central banks to manage interest rates in the economy. It basically consists in the central bank setting a target for a specific yield on government bonds with a certain maturity date, typically long-term, and then buying bonds on the open market or directly intervening in the bond market to ensure that the market yield stays at or near that target level. The central bank doesn't take any action if bond yields of targeted maturities stay below this ceiling. However, if prices go up above this price floor, the central bank intervenes by purchasing targeted-maturity bonds to increase demand and so the price of these bonds, allowing to lower yields below the ceiling (given the inversely proportional relation).

Governments employ YCC for various reasons, with the primary motive being to bolster the economy during times of turmoil. Take the COVID-19 pandemic for instance: central banks worldwide resorted to YCC policies to stabilize financial markets and provide aid to the economy. With low and steady interest rates, YCC can offset the adverse economic impacts of a crisis and lend a sense of stability and predictability to the market. In addition, governments use YCC to support specific policy objectives, such as boosting inflation or fostering economic growth. For example, the Bank of Japan has employed YCC to try to achieve a predetermined inflation rate in the economy, whereas the Federal Reserve has used it to boost the economic recovery post the financial crisis.

As seen above, the purpose of YCC is to maintain lower interest rates and boost overall economic activity. This happens through two main channels. Firstly, lower interest rates imply lower cost of debt, which ultimately leads to an increase in borrowing that is directed to an increase in consumption and/or in investments. Secondly, lower interest rates also boost asset prices leading to an overall increase in wealth thus allowing more consumer spending. In addition, YCC can help to reduce volatility in the economy by anchoring inflation expectations, therefore making it easier for businesses and individuals to plan for the future. This might be very important for central banks that have struggled with low inflation in recent years as YCC can help ensure that inflation expectations do not fall too far below the central bank's target level.

Unfortunately, YCC also has its limitations. One potential issue is that it may compromise the transparency of the central bank's decision-making process. When the central bank intervenes in the bond market to regulate interest rates, it can be challenging for market players to understand the central bank's actual intentions and anticipate its future actions. This can increase market instability and render it more difficult for investors to make informed choices. Furthermore, YCC may distort market signals and produce unintended outcomes. For example, when the central bank sets a specific interest rate target, investors may excessively concentrate on that target and not consider other important market signals. This can lead to improper allocation of capital and potentially create bubbles in specific asset classes.

The use of YCC has become increasingly popular among central banks around the world, particularly in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. In the United States, the Federal Reserve has experimented with YCC in recent years, while the Bank of Japan has been using the tool since 2016.

Japan’s History

Japan’s experience with Yield Curve Control (YCC) began when the Bank of Japan, from now on BoJ, changed its current policy framework to peg the yield on ten-years Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) at zero percent, in a new effort to stimulate the economy. The motivation behind this highly debated choice is to be found in the thirty-years-long Japanese fight against low, or even negative, inflation. Between 1960 and the end of the 1980s, Japan’s economic growth was twice as fast as in the US. This incredible growth, however, was unsustainable in the long-run and brought along signs of economic distress. Indeed, in the early 1990s, the so-called “Bubble Economy” collapsed. After the stock market crash and the banking crisis, core inflation (which does not consider fresh food and energy prices) peaked at slightly above 3% in 1991, and then began declining: by 1994 it was below 1%. Deflation came largely unanticipated, making the adjustment process particularly difficult for Japan. Economic growth and demand sharply decreased, dissipating inflationary pressures.

The obvious response of the BoJ was to aggressively lower the interest rate from 8.5% in 1991 to a previously unheard level of 0.5% in late 1995. Since then, it has never increased more than that, being frequently brought at 0% or even negative at -0.1%. While usually consumers respond to expansionary monetary policies by spending more, this has not been the case in Japan. Prolonged, unanticipated deflation has annulled monetary policy efficacy, reduced market activities and corporate profitability and raised the burden of both private and public debt. Indeed, the conventional monetary policy framework assumes that the policy rate lies above zero. With the nominal interest rate at the zero lower bound, or even lower, and the economy in a liquidity trap, the only possibility was an unconventional monetary policy. The functioning of such practice has become clearer after the 2008 financial crisis, but BoJ has been a frontrunner in its implementation. But what is an unconventional monetary policy? It is defined as an attempt to extend the scope of what a central bank tries to control beyond the short-term interest rate, in the case of Japan the risk premia of long-term bonds and risky equities. Its use is necessary when there is no room for a further reduction of the interest rate, which was precisely the scenario that the Japanese economy was facing.

In 2001, the BoJ established its Quantitative Easing strategy, based on large purchases of JGBs and other assets. The program, however, had a relatively small scope if compared with what other central banks did during the financial crisis. In 2013 the Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE) was adopted. It included a massive asset purchase, mostly of JGBs, a commitment to lengthen the maturity of JGBs, in an attempt to lower long-term rates and, finally, a pledge to stick to the new policy framework until inflation would have reached or exceeded its 2% target. After an initial positive response of the inflation rate, both inflation and market expectations fell back at the beginning of 2016. Furthermore, the BoJ held almost 40% of the JGB market, with the perspective to further increase the share, being inflation well below the target. Dealer surveys began to point out a deterioration in the JGB market functioning. The BoJ reacted to the bad news by cutting the interest rate from 0.1% to -0.1%. Eventually, the policy led to a negative rate on ten-year JGBs. This situation, which was expected to persist for a relatively long time, could erode lending margins and consequently endanger financial institutions. The yield curve flattened and banks seriously worried about their returns on investment.

That is precisely why, at the end of 2016, the BoJ adopted the previously stated Yield Curve Control policy. The announcement made it clear that the QQE program would have continued, but now the rate on ten-year bonds could no more fall below 0%. The idea was to control the shape of the yield curve so that the short-term rates could be cut without depressing long-term ones. By increasing the spread between the yields of short-term (negative) and long-term bonds, the yield curve would have become steeper and banks’ profitability would have increased. The aim was to foster economic activity and, thus, reaching a higher inflation rate.

The long-term yield on government bonds soon settled close to the target, where it remained relatively stable. However, the inflation rate did not react as hoped by the BoJ, which was thus forced to keep the YCC longer than initially expected. In turn, this led to the stagnation of trading in the bond market. To address this side-effect, the BoJ reduced its intervention in the JGB market by letting the ten-year yield to move by 0.1% in either direction in 2018. The possible movement above or below zero was extended to 0.25% in 2021.

Has YCC worked? The clear benefit it introduced was that, with yield curve stability, the BoJ gained credibility and could therefore consistently reduce its purchases of bonds, avoiding too heavy interventions in the JGB market. As for reversing the deflationary trend, many argue that if monetary stimuli alone could push Japanese inflation up to the target, QQE would have already served the purpose. Anyway, it is impossible to know if the situation would have become even worse without YCC.

As for the current situation, inflation is above the target for the first time since the 1990s. However, the consequences of COVID-19 and of the recent global geopolitical situation have completely changed the whole macroeconomic scenario, making it even harder to clearly identify and separate the actual causes of this recent growth of the Japanese inflation rate.

Japan’s experience with Yield Curve Control (YCC) began when the Bank of Japan, from now on BoJ, changed its current policy framework to peg the yield on ten-years Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) at zero percent, in a new effort to stimulate the economy. The motivation behind this highly debated choice is to be found in the thirty-years-long Japanese fight against low, or even negative, inflation. Between 1960 and the end of the 1980s, Japan’s economic growth was twice as fast as in the US. This incredible growth, however, was unsustainable in the long-run and brought along signs of economic distress. Indeed, in the early 1990s, the so-called “Bubble Economy” collapsed. After the stock market crash and the banking crisis, core inflation (which does not consider fresh food and energy prices) peaked at slightly above 3% in 1991, and then began declining: by 1994 it was below 1%. Deflation came largely unanticipated, making the adjustment process particularly difficult for Japan. Economic growth and demand sharply decreased, dissipating inflationary pressures.

The obvious response of the BoJ was to aggressively lower the interest rate from 8.5% in 1991 to a previously unheard level of 0.5% in late 1995. Since then, it has never increased more than that, being frequently brought at 0% or even negative at -0.1%. While usually consumers respond to expansionary monetary policies by spending more, this has not been the case in Japan. Prolonged, unanticipated deflation has annulled monetary policy efficacy, reduced market activities and corporate profitability and raised the burden of both private and public debt. Indeed, the conventional monetary policy framework assumes that the policy rate lies above zero. With the nominal interest rate at the zero lower bound, or even lower, and the economy in a liquidity trap, the only possibility was an unconventional monetary policy. The functioning of such practice has become clearer after the 2008 financial crisis, but BoJ has been a frontrunner in its implementation. But what is an unconventional monetary policy? It is defined as an attempt to extend the scope of what a central bank tries to control beyond the short-term interest rate, in the case of Japan the risk premia of long-term bonds and risky equities. Its use is necessary when there is no room for a further reduction of the interest rate, which was precisely the scenario that the Japanese economy was facing.

In 2001, the BoJ established its Quantitative Easing strategy, based on large purchases of JGBs and other assets. The program, however, had a relatively small scope if compared with what other central banks did during the financial crisis. In 2013 the Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE) was adopted. It included a massive asset purchase, mostly of JGBs, a commitment to lengthen the maturity of JGBs, in an attempt to lower long-term rates and, finally, a pledge to stick to the new policy framework until inflation would have reached or exceeded its 2% target. After an initial positive response of the inflation rate, both inflation and market expectations fell back at the beginning of 2016. Furthermore, the BoJ held almost 40% of the JGB market, with the perspective to further increase the share, being inflation well below the target. Dealer surveys began to point out a deterioration in the JGB market functioning. The BoJ reacted to the bad news by cutting the interest rate from 0.1% to -0.1%. Eventually, the policy led to a negative rate on ten-year JGBs. This situation, which was expected to persist for a relatively long time, could erode lending margins and consequently endanger financial institutions. The yield curve flattened and banks seriously worried about their returns on investment.

That is precisely why, at the end of 2016, the BoJ adopted the previously stated Yield Curve Control policy. The announcement made it clear that the QQE program would have continued, but now the rate on ten-year bonds could no more fall below 0%. The idea was to control the shape of the yield curve so that the short-term rates could be cut without depressing long-term ones. By increasing the spread between the yields of short-term (negative) and long-term bonds, the yield curve would have become steeper and banks’ profitability would have increased. The aim was to foster economic activity and, thus, reaching a higher inflation rate.

The long-term yield on government bonds soon settled close to the target, where it remained relatively stable. However, the inflation rate did not react as hoped by the BoJ, which was thus forced to keep the YCC longer than initially expected. In turn, this led to the stagnation of trading in the bond market. To address this side-effect, the BoJ reduced its intervention in the JGB market by letting the ten-year yield to move by 0.1% in either direction in 2018. The possible movement above or below zero was extended to 0.25% in 2021.

Has YCC worked? The clear benefit it introduced was that, with yield curve stability, the BoJ gained credibility and could therefore consistently reduce its purchases of bonds, avoiding too heavy interventions in the JGB market. As for reversing the deflationary trend, many argue that if monetary stimuli alone could push Japanese inflation up to the target, QQE would have already served the purpose. Anyway, it is impossible to know if the situation would have become even worse without YCC.

As for the current situation, inflation is above the target for the first time since the 1990s. However, the consequences of COVID-19 and of the recent global geopolitical situation have completely changed the whole macroeconomic scenario, making it even harder to clearly identify and separate the actual causes of this recent growth of the Japanese inflation rate.

The move from 0.25 to 0.5

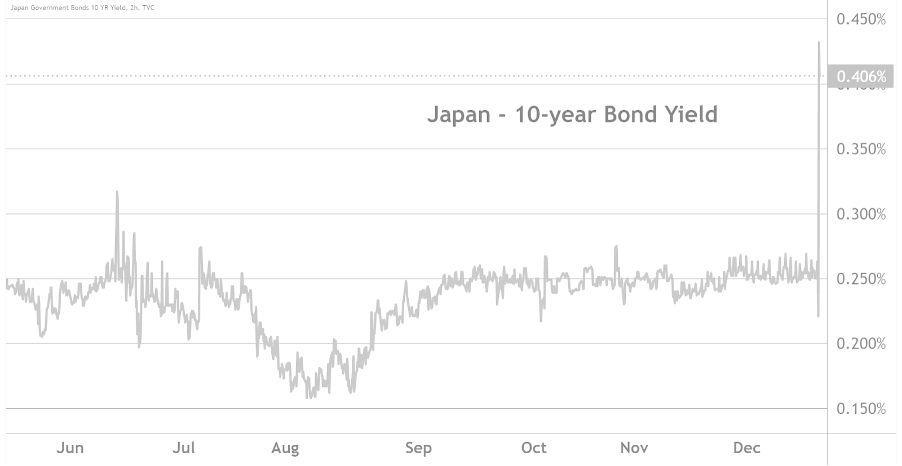

Considering the aforementioned events, on December 20th 2022, the Bank of Japan made the decision to lift its cap on 10-year government bond yields from 0.25% to 0.5%. This decision came after the BoJ had maintained the 0.25% cap for over five years as part of its Yield Curve Control. The move came unexpected in the market as clues about the Central Bank aligning their monetary policy to that of other developed nations were spreading but it seemed unlikely that such a change would happen before the change in Governor: in fact this move happened after the last meeting of the year, as Gov. Haruhiko Kuroda concluded his 10 years of office. The announcement sent the 10 years bond yield up to 0.4% by the end of the day.

Considering the aforementioned events, on December 20th 2022, the Bank of Japan made the decision to lift its cap on 10-year government bond yields from 0.25% to 0.5%. This decision came after the BoJ had maintained the 0.25% cap for over five years as part of its Yield Curve Control. The move came unexpected in the market as clues about the Central Bank aligning their monetary policy to that of other developed nations were spreading but it seemed unlikely that such a change would happen before the change in Governor: in fact this move happened after the last meeting of the year, as Gov. Haruhiko Kuroda concluded his 10 years of office. The announcement sent the 10 years bond yield up to 0.4% by the end of the day.

Japanese 10-year government Bond Yields

Source: TradingView

Source: TradingView

The effect of this policy on the price of the Japanese Yen has been mixed: at first impact the value of the Yen rose with the announcement, before the announcement a dollar bought 137 Yen, value that fell to 133 due to the aftermath of the bond cap being partially lifted. However, this effect has been rather limited as the central bank had been hinting at its intentions for some time. In the last few months the BoJ had been gradually reducing its bond purchases, signaling its move towards a more “in-line” monetary policy. As a result, investors had already priced in the possibility of a lift in the yield cap, and the announcement had limited effect on the short-term market for CB currency and reserve deposits

Another reason for the controlled impact on the yen and the decision behind the BoJ’s announcement is that other central banks have also been moving towards a tighter monetary policy. The Federal Reserve has already started to taper its bond-purchasing programs, and the European Central Bank followed suit as it was expected. Due to these foreign decisions, the yield differential between Japanese bonds and those of other countries is going to be less impactful than it would have otherwise been, and the BoJ's Yield Curve Control policy falls in line with the global sentiment.

A factor to support the existing governor’s choice is also the recovery of the Japanese economy after the Pandemic. The BoJ's quarterly Tankan survey showed that business sentiment had improved for the second straight quarter, with large manufacturers reporting the highest level of optimism in over three years. Additionally, the unemployment rate had fallen to pre-pandemic levels, and household spending had rebounded. These encouraging signs backed up the Central Bank decision as the economy seemed more prepared to withstand a change in the monetary policy.

Another reason for the controlled impact on the yen and the decision behind the BoJ’s announcement is that other central banks have also been moving towards a tighter monetary policy. The Federal Reserve has already started to taper its bond-purchasing programs, and the European Central Bank followed suit as it was expected. Due to these foreign decisions, the yield differential between Japanese bonds and those of other countries is going to be less impactful than it would have otherwise been, and the BoJ's Yield Curve Control policy falls in line with the global sentiment.

A factor to support the existing governor’s choice is also the recovery of the Japanese economy after the Pandemic. The BoJ's quarterly Tankan survey showed that business sentiment had improved for the second straight quarter, with large manufacturers reporting the highest level of optimism in over three years. Additionally, the unemployment rate had fallen to pre-pandemic levels, and household spending had rebounded. These encouraging signs backed up the Central Bank decision as the economy seemed more prepared to withstand a change in the monetary policy.

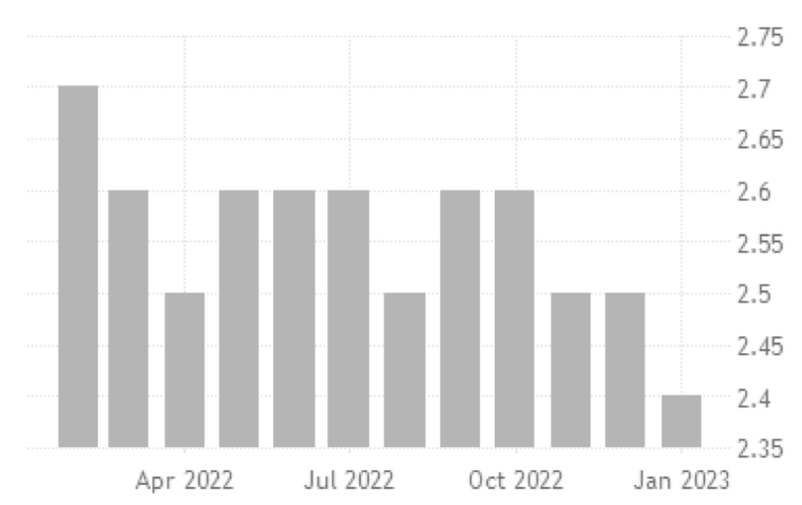

Japan’s Unemployment Rate over the past year

Source: TradingView

Source: TradingView

These reasons do not deny the possible implications of such a move: this new monetary policy could lead to increased volatility in the Japanese bond market. As the BoJ reduces its purchases of government bonds, the market will have to absorb more supply, which could lead to fluctuations in prices and yields. This could have knock-on effects for other financial markets, including the currency market.

Another crucial effect on the Japanese economy would be the shift to higher borrowing costs for the Japanese government. Japan has one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the world, and any increase in borrowing costs could put further strain on the government's finances. Additionally, the possible increase in the price of the Yen could lead to decreases in profit for many export companies, which have benefited from the BoJ’s monetary policy in the past, explaining the uncertain response of the Nikkei stock market after the Central Bank’s announcement.

Japanese interest rates are still well below the average of those in the United States or Europe. This can be attributed both to the larger growth in inflation in the US and EU, and to the different scenario present in Japan given its past struggles. The key rates of the Fed reached a level around 4.5% in December 2022, while the European Central Bank set its key rate expectations to 2%, substantially raising it from its 1.5% previous target. This gap still leaves a breather for the BoJ to place the Yield of their long-term bonds, with less controlled short-term ones.

Another crucial effect on the Japanese economy would be the shift to higher borrowing costs for the Japanese government. Japan has one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the world, and any increase in borrowing costs could put further strain on the government's finances. Additionally, the possible increase in the price of the Yen could lead to decreases in profit for many export companies, which have benefited from the BoJ’s monetary policy in the past, explaining the uncertain response of the Nikkei stock market after the Central Bank’s announcement.

Japanese interest rates are still well below the average of those in the United States or Europe. This can be attributed both to the larger growth in inflation in the US and EU, and to the different scenario present in Japan given its past struggles. The key rates of the Fed reached a level around 4.5% in December 2022, while the European Central Bank set its key rate expectations to 2%, substantially raising it from its 1.5% previous target. This gap still leaves a breather for the BoJ to place the Yield of their long-term bonds, with less controlled short-term ones.

Future outlook on Japan’s economy

The Japanese economy has been facing a unique situation of deflation for many years. The inflation expectations of consumers play a key role in the development of inflation dynamics in the country, and for the past 30 years, consumers have been right about their predicted inflation. This has anchored their inflation forecasts, which will now shape the future inflationary environment in Japan. It is important to note that consumers trust their own forecasts rather than the statements of the Bank of Japan, which has not been able to keep inflation near its target.

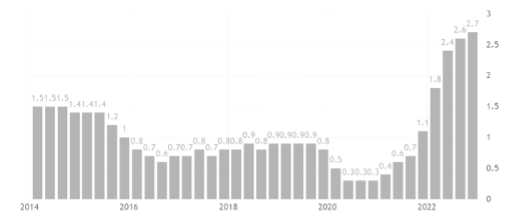

To understand the future outlook of the inflation situation in Japan, it is important to look at both short-term and long-term inflationary expectations of consumers. Since 2014, inflation expectations in Japan have averaged 1% and have been on an increasing trend since the low points of the COVID-19 pandemic, where they were as low as 0.3%. Recent surveys show that expectations in March have hit record high levels at 2.67%. However, this only represents one-year inflation expectations and is not enough to make any statements about the long-term inflation without analyzing other aspects.

The Japanese economy has been facing a unique situation of deflation for many years. The inflation expectations of consumers play a key role in the development of inflation dynamics in the country, and for the past 30 years, consumers have been right about their predicted inflation. This has anchored their inflation forecasts, which will now shape the future inflationary environment in Japan. It is important to note that consumers trust their own forecasts rather than the statements of the Bank of Japan, which has not been able to keep inflation near its target.

To understand the future outlook of the inflation situation in Japan, it is important to look at both short-term and long-term inflationary expectations of consumers. Since 2014, inflation expectations in Japan have averaged 1% and have been on an increasing trend since the low points of the COVID-19 pandemic, where they were as low as 0.3%. Recent surveys show that expectations in March have hit record high levels at 2.67%. However, this only represents one-year inflation expectations and is not enough to make any statements about the long-term inflation without analyzing other aspects.

Japanese Expected Inflation Rates: 2014 to 2022

Source: TradingEconomics

Source: TradingEconomics

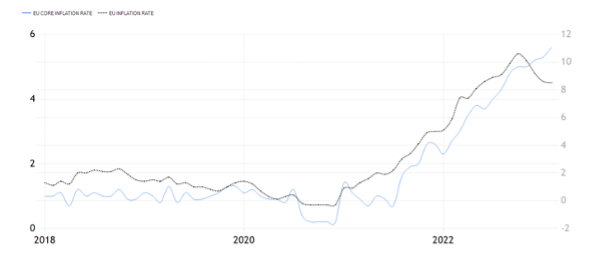

While inflation expectations are crucial in understanding the demand side of inflation, the supply side also plays a significant role in the long-run behavior of inflation. The war in Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic have disrupted the global supply chain, leading to a rise in prices that for now has been seen as temporary by the consumers. However, if this turns out to be a fundamental shift in the world causing price rises, inflation expectations may continue to rise. Right now both the CPI and the Core Core CPI (less fresh-foods and energy) continue to rise but we can expect to see a similar case to the one in the Euro Area where despite declining inflation data due to strong price declines on raw materials, it is clear that the Core CPI does not slow down and probably will become entrenched for a long time at values much higher than the previous ones. It is possible that inflation will consolidate above the target of the Bank of Japan. This could negatively impact the Japanese economy, which has relied on cheap money for decades and has the highest ratio of government debt to GDP (260%).

EU core Inflation Rate against EU Inflation rate: 2018 to 2022

Source: TradingEconoimcs

Source: TradingEconoimcs

Controlling the effects of inflation largely depends on the policy changes implemented by the BoJ. It is widely accepted that the BoJ will need to tighten its monetary policy, but the extent to which they are willing to do so remains a question. One approach would be to continue increasing the YCC ceiling, with some Citigroup strategists predicting a target of 100 basis points by the time the new governor takes office. However, this carries the risk of injecting excessive money supply into the economy, which could exacerbate the situation by leading to even higher inflation. High inflation would lead to lower bond prices and higher yields, forcing the BoJ to purchase more bonds and inject even more money into the economy, thus perpetuating the cycle. This is why many strategists suggest that the long-term scenario involves the BoJ abandoning the YCC altogether, with some predicting that the yield target could be dropped as early as the beginning of summer. It may be advisable to switch to controlling inflation through the key rate, while letting the yields be the result of the market equilibrium, which will allow gaining consumer confidence through transparent goals and ways to achieve them. Because of that, the future outlook of the inflation situation in Japan will depend on both the supply-side dynamics affecting the economy and the actions that the BoJ will take to control the consumers’ inflation expectations.

Conclusion

It is clear that the YCC policy has been a critical component of Japan's economic growth and stability. Throughout its history, the policy has navigated the intricacies of the past, present, and future of the Japanese economy, demonstrating its adaptability and resilience. However, it is also essential to recognize the policy's impact beyond Japan's borders, as the world's third largest economy. Any changes to Japan's yields have the potential to reverberate throughout the global market, making the YCC a topic of global significance.

As we look ahead, it is apparent that the YCC policy will continue to face new challenges and adapt to the new economic landscape. The BoJ will need to increase yield ceilings significantly to prevent inflation from spiraling out of control, a stark contrast to the previous goal of keeping yields low to boost inflation. Nevertheless, with a long track record of battling deflation, we can be confident that the BoJ has mastered monetary tools that will allow it to take control of the situation.

It is clear that the YCC policy has been a critical component of Japan's economic growth and stability. Throughout its history, the policy has navigated the intricacies of the past, present, and future of the Japanese economy, demonstrating its adaptability and resilience. However, it is also essential to recognize the policy's impact beyond Japan's borders, as the world's third largest economy. Any changes to Japan's yields have the potential to reverberate throughout the global market, making the YCC a topic of global significance.

As we look ahead, it is apparent that the YCC policy will continue to face new challenges and adapt to the new economic landscape. The BoJ will need to increase yield ceilings significantly to prevent inflation from spiraling out of control, a stark contrast to the previous goal of keeping yields low to boost inflation. Nevertheless, with a long track record of battling deflation, we can be confident that the BoJ has mastered monetary tools that will allow it to take control of the situation.

By Amos Appendino, Chiara Evangelisti, Emanuele Tartaglini, Maxim Shkolnikov

Sources:

- The Financial Times

- International Monetary Fund

- The Economist

- The Wall Street Journal

- Reuters

- World Economic Forum

- Trading Economics

- TradingView