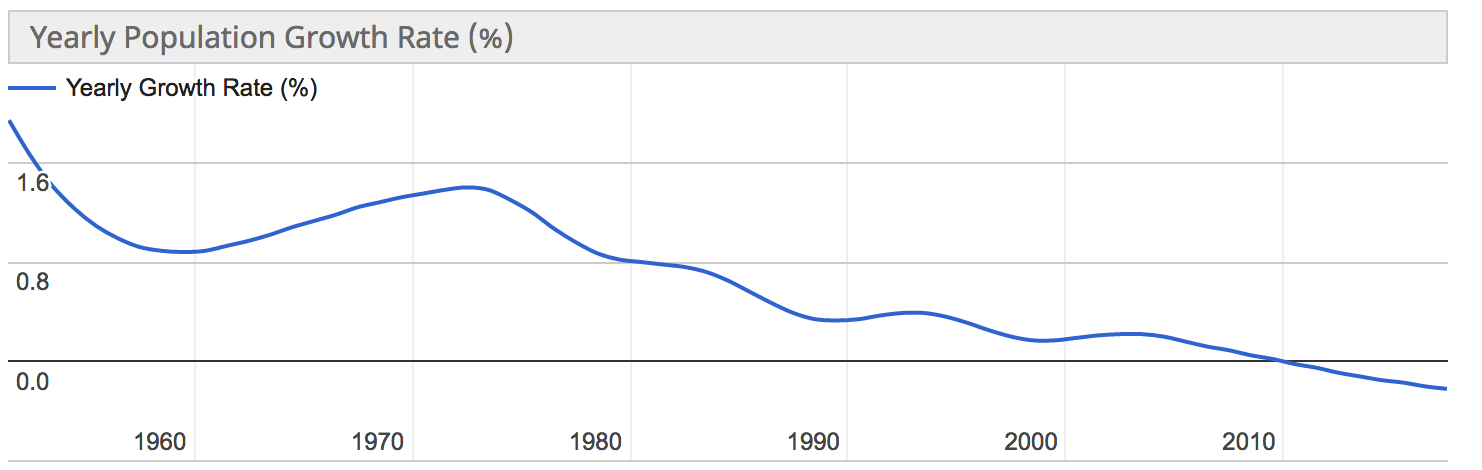

One of the biggest issues Japan is currently facing is the threat coming from a population that is getting older and older.

Over the last 25 years, Japan’s economy squeezed due to low fertility and low consumption rates: the high providential costs generated by the aging population weight upon youngsters, which in turn often decide not to have children. In a population of 127 million, those over 60 years old represent the biggest demographic group. Strange as it may seem, the sales of diapers for adults in Japan have exceeded those in baby diapers last year...

Indeed, there are now 7 retirees for every 10 salaried workers — and the ratio is rising fast. If this trend continues, 34% of the population might disappear by 2100.

Over the last 25 years, Japan’s economy squeezed due to low fertility and low consumption rates: the high providential costs generated by the aging population weight upon youngsters, which in turn often decide not to have children. In a population of 127 million, those over 60 years old represent the biggest demographic group. Strange as it may seem, the sales of diapers for adults in Japan have exceeded those in baby diapers last year...

Indeed, there are now 7 retirees for every 10 salaried workers — and the ratio is rising fast. If this trend continues, 34% of the population might disappear by 2100.

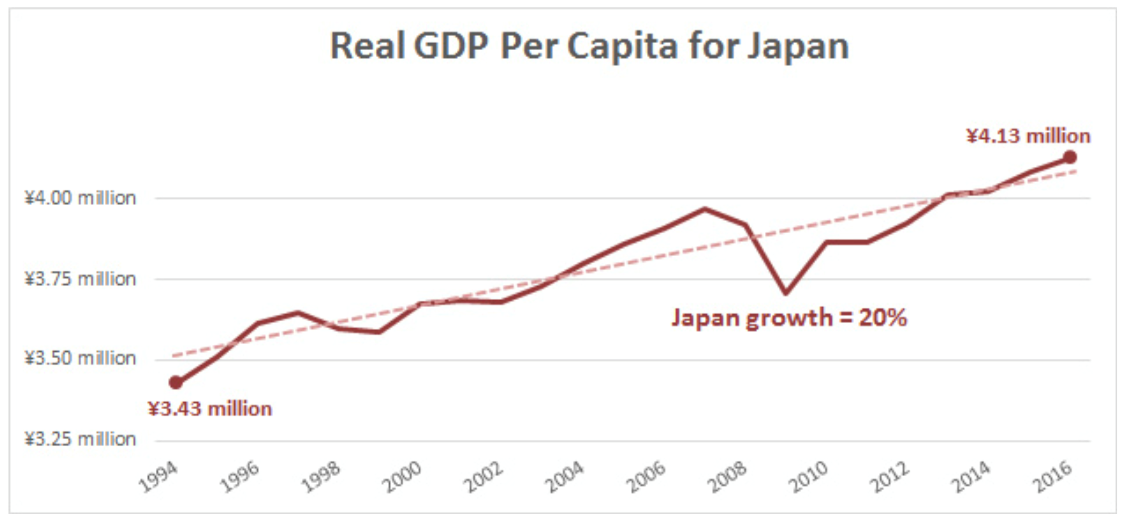

In this apocalyptic scenario, Japanese economy also shows some positive figures.

If we combine the fact that GDP per capita has been growing during the past 20 years with the declining population, we can infer that there is not a productivity problem in the country.

If we combine the fact that GDP per capita has been growing during the past 20 years with the declining population, we can infer that there is not a productivity problem in the country.

Still, although Japan’s government is inciting firms to increase home investments and raise wages to stimulate the economy and escape deflation, recovery is a slow process. Moreover, the Bank of Japan’s monetary stimuli unleashed in 2013 have only slightly contributed to economic recovery.

Looking back

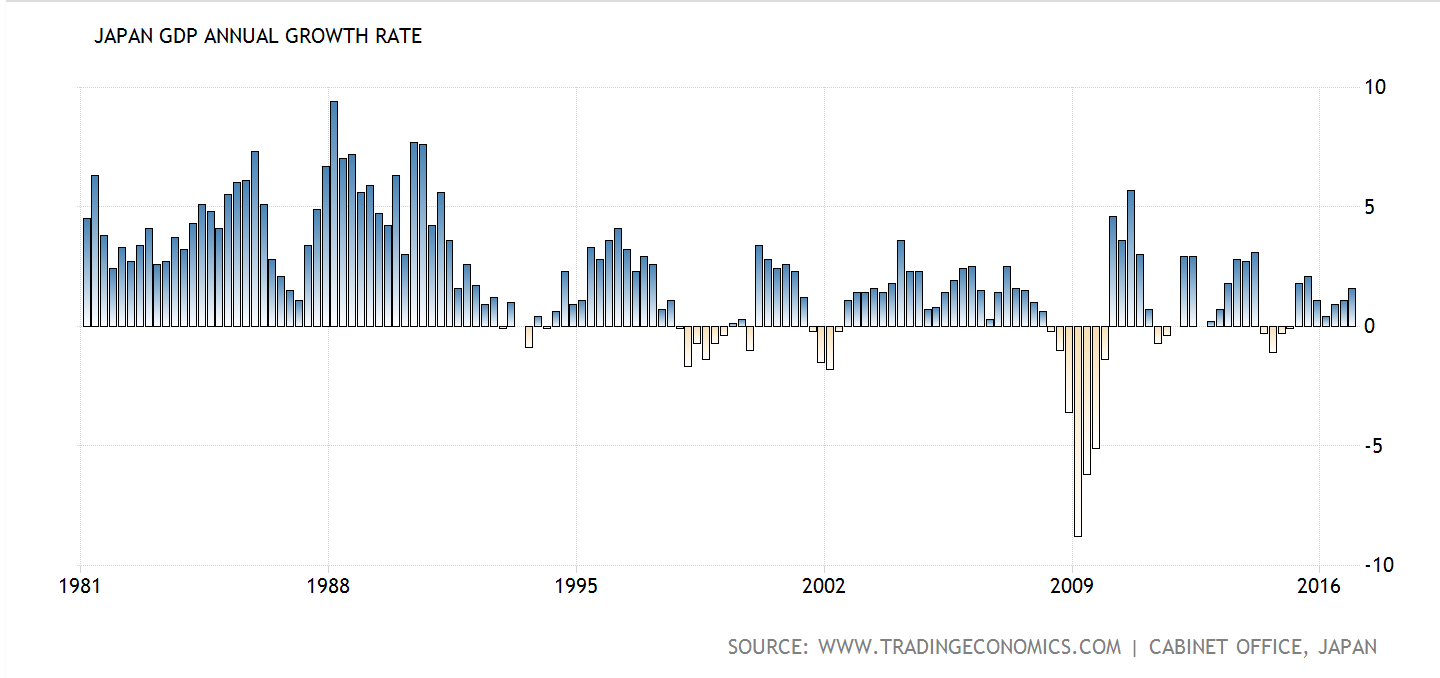

Japan moved from being a poor country after WWII to a major industrial power in a few decades. After the “Japanese miracle” of the golden 60s and 70s, annual growth has decreased and got stuck to 1%, recessions have been frequent and prices have been falling since the 1990s. During the 70s, Japanese economy grew at a 7.7% rate, threatening to reach and even surpass US GDP. Then, unexpectedly, the Japanese pace slowed down.

Looking back

Japan moved from being a poor country after WWII to a major industrial power in a few decades. After the “Japanese miracle” of the golden 60s and 70s, annual growth has decreased and got stuck to 1%, recessions have been frequent and prices have been falling since the 1990s. During the 70s, Japanese economy grew at a 7.7% rate, threatening to reach and even surpass US GDP. Then, unexpectedly, the Japanese pace slowed down.

The country faced deflationary episodes in the last decades (inflation never exceeded zero between 1993 and 2005 and was negative between 1998 and 2005). Moreover, while per capita GDP growth in the 1970–1990 period was 3.2%, it slowed down to only 0.7% in the 1991–2005 period.

Recent figures

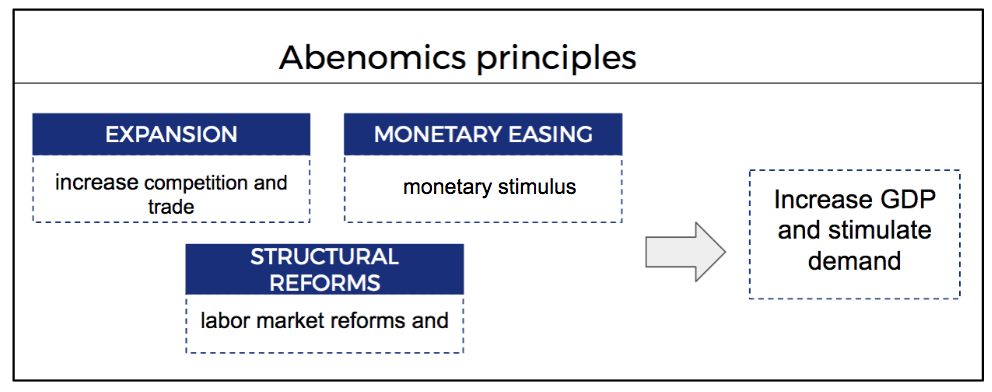

Japanese government has made many attempts to revitalize the economy and the so-called Abenomics (from Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s economic policies advocated in 2013) focuses on three main issues: expansion, monetary easing, and structural reforms. More specifically, short-term goals are stimulating demand and GDP growth by means of more competition and trade, labor market reforms and monetary stimulus. However, the success of Abenomics is still uncertain: Japan economy grew only by 2.2% in real terms since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe promised beneficial structural reforms and GDP QoQ growth in Q4 of 2016 was 0.3.

Recent figures

Japanese government has made many attempts to revitalize the economy and the so-called Abenomics (from Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s economic policies advocated in 2013) focuses on three main issues: expansion, monetary easing, and structural reforms. More specifically, short-term goals are stimulating demand and GDP growth by means of more competition and trade, labor market reforms and monetary stimulus. However, the success of Abenomics is still uncertain: Japan economy grew only by 2.2% in real terms since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe promised beneficial structural reforms and GDP QoQ growth in Q4 of 2016 was 0.3.

Core consumer prices increased slightly during the last two months and unemployment rate hit 20-year low (2.8% in February). Some economists think the full employment (an economic situation in which all available labor resources are being used in the most efficient way possible) has almost been reached.

After 20 years of stagnation and frequent recessions, Japan’s economy is growing again, despite its large public debt (246% of GDP).

Moreover, Bank of Japan QE drove long-term bond yields to record lows and Japanese government bond follow this trend.

After 20 years of stagnation and frequent recessions, Japan’s economy is growing again, despite its large public debt (246% of GDP).

Moreover, Bank of Japan QE drove long-term bond yields to record lows and Japanese government bond follow this trend.

As far as trade is concerned, Japan’s exports might suffer from China’s slowdown and from uncertainties throughout all Asia. For 30 years until 2010, every year Japan registered a trade surplus. However, in 2014 Japan recorded an unexpectedly huge trade deficit, as the weaker yen had made the cost of imports soar.

All in all, what should we expect from Abenomics? Up to now, Japanese consumers have not benefited much from Shinzo Abe’s policies, with the price of many imported goods increasing due to the weak yen and not-rising wages. Furthermore, demand for consumer goods has been weakened by the rise in Japan national sales tax from 5% to 8% in April of 2015.Indeed, the Bank of Japan explicitly acknowledged the declining effectiveness of its QEs “with a negative interest rate framework” last summer, so we can reasonably expect a different approach for the future.

In conclusion, if it is true what most studies show, namely that one of the main features of the unsustainably ageing population is that young Japanese mostly dedicate their time to work instead of socializing and thinking about building a family, we might consider Japan’s main economic issues as also social ones. Have we reached a paradox? Would Japanese economy be better off if young generations slowed down the pace of work? The only sure thing is that this is the picture of a country calling out for both social and economic reforms.

Beatrice Luzzi

All in all, what should we expect from Abenomics? Up to now, Japanese consumers have not benefited much from Shinzo Abe’s policies, with the price of many imported goods increasing due to the weak yen and not-rising wages. Furthermore, demand for consumer goods has been weakened by the rise in Japan national sales tax from 5% to 8% in April of 2015.Indeed, the Bank of Japan explicitly acknowledged the declining effectiveness of its QEs “with a negative interest rate framework” last summer, so we can reasonably expect a different approach for the future.

In conclusion, if it is true what most studies show, namely that one of the main features of the unsustainably ageing population is that young Japanese mostly dedicate their time to work instead of socializing and thinking about building a family, we might consider Japan’s main economic issues as also social ones. Have we reached a paradox? Would Japanese economy be better off if young generations slowed down the pace of work? The only sure thing is that this is the picture of a country calling out for both social and economic reforms.

Beatrice Luzzi