Introduction

Sustainable development is of utmost importance for political and economic decisions. Issuers of green, social, and sustainable bonds are contributing to the fight against climate change and committing to inclusive and sustainable growth. In this article, we aim to highlight the significant evolution of sustainable finance in the Latin American region. Undoubtedly, governments, companies, and investors are aware of the potential for green, social, and sustainable bonds to raise funds for projects that contribute to the economic, social, and environmental development of Latin America.

ESG Bond Issuance in Latin America

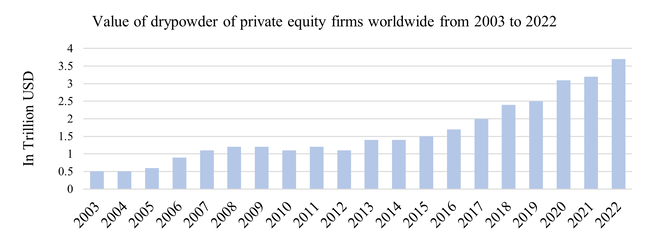

Overall, the use of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) instruments by debt issuers from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) in international markets has grown very rapidly in the past two years. Especially, the international issuance of sustainability-linked bonds (SLB) by companies in the region grew exponentially in 2021, according to a report by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)- from which we show an insightful graph below.

Source: ECLAC (2022)

It is worth to notice that in 2021 most issuers in this segment are from Brazil, Mexico, and Chile with 60%, 28%, and 8% of the market segment, respectively. The significant surge of SLBs in countries such as Mexico or Brazil is explained by the interest of private corporate issuers to show how ESG issues are main concerns in defining their corporate strategy. In fact, in 2021 the top three issuers were Suzano (a forestry company from Brazil), FEMSA (a food retail and bottling company from Mexico) and Orbia Advance Corp (an industrial conglomerate from Mexico), jointly representing nearly half – US$ 4.25 billion- of all SLB volume.

What about sovereign issuance? “In Latin America, sovereigns are finely attuned to the impact that climate change will have predominantly in emerging markets, and are proactively taking steps to support initiatives that drive sustainability and equality in their local communities,” explains Monica Hanson, Head of Official Institutions Coverage, Americas, BNP Paribas.

The most virtuous example is Chile. In recent years, Chile has increased its commitment to mitigate climate change and protect the environment. To reach a zero net carbon economy by 2050, the Chilean government have created specialized areas to address climate change, promote cooperation between the public and the private sector and align incentives from different stakeholders toward this goal.

Already before the pandemic, Chile was the first country in the Americas to issue green bonds (varying from 12 to 30 years of maturity and coupon varying between 3.870 and 5.413 respectively). Since 2020 Chile further expanded its debt instruments by issuing social bonds (with maturity varying from 6 to 50 years and coupons varying from 3.682 and 5.485 respectively) and sustainability bonds (maturity from 6 to 40 years and coupons from 4.801 and 5.553 respectively). On March 7, Chile became the first country in the world to issue an SLB, obtaining remarkable results, despite the high volatility and uncertainty in the global financial markets.

The US dollar bond maturing in 2042 was placed at US$ 2 billion with a coupon of 5.705. The operation was remarkably successful, achieving a demand of US$ 8.1 billion, which four times oversubscribed the amount placed.

Considering this operation, since 2019 the Chilean government issued the equivalent of approximately US$ 33 billions in thematic bonds, of which US$ 17.8 billions are social bonds, US$ 7.7 billions are green bonds, US$ 5.5 billion are sustainable bonds and US$ 2 billions are SLBs (the ones issued on March 7). With this issuance, thematic bonds represent 28.7% of the stock of central government debt, a fraction among the largest in the world.

This SLB Framework adopted by Chile is aligned with ICMA's Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles published in June 2020, complying with five core components: “selection of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), calibration of Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs), bond characteristics, reporting, review and verification.” [1]. Chile’s issuance is linked to two KPIs: “(i) a specific target for absolute greenhouse gas emissions and (ii) achieving half of electric power generation from Non-Conventional Renewable Energy sources (NCRE) over the next six years, increasing to 60% by 2032.” [2]. Doing so, Chile becomes the first government in the world to link its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) commitment on climate change to a bond issuance.

While, differently from Chile, not having a history of green, social, and sustainable bonds issuance, on October 20, also Uruguay issued its first SLB, with a step-down mechanism that is activated if determined environmental targets are reached. Issuing a bond that links the coupon to compliance with environmental goals, the Uruguayan government aim to align sovereign debt policy with the climate goals that the country set in its first Naturally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement.

The issuance of the 12-year bond with a coupon of 4.975 attracted 188 investors from around the world, of whom 21% are new holders of Uruguayan debt. Total demand for the bond was US$ 3.96 billions, exceeding the US$ 1.5 billions Uruguay issued.

The SLB Framework adopted by Uruguay set as targets (i) the reduction of GHG emissions and (ii) the conservation of the country’s native forest area.

Among other LAC countries, also Peru and Mexico are committing to significant ESG sovereign issuance, while others comparable countries, such as Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, and Panama, are still a step behind.

Despite the slower pace of Peru’s market of green, social, and sustainable bonds expansion, there have been and there are significant movements to leverage sustainable finance in the country. Indeed, Peru is Latin America’s sustainable finance pioneer: the Peruvian company Energía Eólica S.A. was the first green bond issuer in the region in December 2014 with a 20-year, US$ 204 millions deal to finance two wind energy projects.

Then, Peru successfully issued three thematic sovereign bonds in November 2021. The deals are part of the Government’s strategy in response to the pandemic and aim to address the economic, environmental, and social challenges of the country.

The government began with two sustainability bonds, one with 12-year maturity worth US$ 2.3 billion with a coupon of 3.000 and a US$ 1 billion 50-year maturity with a coupon of 3.600. Two weeks later, Peru issued a 15-year EUR 1 billion social bond with a coupon of 4.846. All deals were at least two times oversubscribed and attracted international investors.

The Sustainable Framework adopted by Peru establishes the eligible categories to refinance 2021- 2022 government expenditures, which include: “social housing, education, and health services; financial support to MSMEs and vulnerable people; green buildings, renewable energy, energy efficiency, low-carbon transport, water infrastructure, sustainable management of natural resources, agriculture, and waste management.” [3]

Similarly, Mexico is increasing its green, social, and sustainable bond issuances in recent years too: with a few in 2020 and 2021, 2022 is a record year with the issuance of several sustainability bonds (with maturity ranging from 3 to 20 years with coupons varying from 1.000 for the 3-years coupon bond to 4.875 for the 11-year one). According to experts, these bonds can be key to a sustainable transition in the financial sector and securities markets of the country. However, the availability, transparency, and quality of information on the bonds are key to this scope.

What about sovereign issuance? “In Latin America, sovereigns are finely attuned to the impact that climate change will have predominantly in emerging markets, and are proactively taking steps to support initiatives that drive sustainability and equality in their local communities,” explains Monica Hanson, Head of Official Institutions Coverage, Americas, BNP Paribas.

The most virtuous example is Chile. In recent years, Chile has increased its commitment to mitigate climate change and protect the environment. To reach a zero net carbon economy by 2050, the Chilean government have created specialized areas to address climate change, promote cooperation between the public and the private sector and align incentives from different stakeholders toward this goal.

Already before the pandemic, Chile was the first country in the Americas to issue green bonds (varying from 12 to 30 years of maturity and coupon varying between 3.870 and 5.413 respectively). Since 2020 Chile further expanded its debt instruments by issuing social bonds (with maturity varying from 6 to 50 years and coupons varying from 3.682 and 5.485 respectively) and sustainability bonds (maturity from 6 to 40 years and coupons from 4.801 and 5.553 respectively). On March 7, Chile became the first country in the world to issue an SLB, obtaining remarkable results, despite the high volatility and uncertainty in the global financial markets.

The US dollar bond maturing in 2042 was placed at US$ 2 billion with a coupon of 5.705. The operation was remarkably successful, achieving a demand of US$ 8.1 billion, which four times oversubscribed the amount placed.

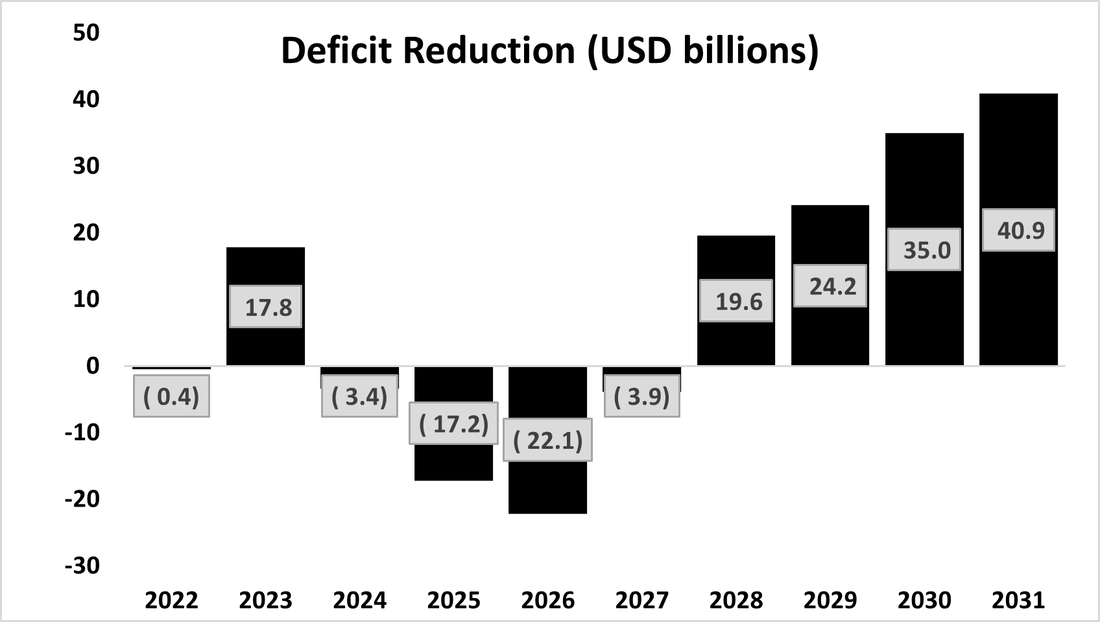

Considering this operation, since 2019 the Chilean government issued the equivalent of approximately US$ 33 billions in thematic bonds, of which US$ 17.8 billions are social bonds, US$ 7.7 billions are green bonds, US$ 5.5 billion are sustainable bonds and US$ 2 billions are SLBs (the ones issued on March 7). With this issuance, thematic bonds represent 28.7% of the stock of central government debt, a fraction among the largest in the world.

This SLB Framework adopted by Chile is aligned with ICMA's Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles published in June 2020, complying with five core components: “selection of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), calibration of Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs), bond characteristics, reporting, review and verification.” [1]. Chile’s issuance is linked to two KPIs: “(i) a specific target for absolute greenhouse gas emissions and (ii) achieving half of electric power generation from Non-Conventional Renewable Energy sources (NCRE) over the next six years, increasing to 60% by 2032.” [2]. Doing so, Chile becomes the first government in the world to link its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) commitment on climate change to a bond issuance.

While, differently from Chile, not having a history of green, social, and sustainable bonds issuance, on October 20, also Uruguay issued its first SLB, with a step-down mechanism that is activated if determined environmental targets are reached. Issuing a bond that links the coupon to compliance with environmental goals, the Uruguayan government aim to align sovereign debt policy with the climate goals that the country set in its first Naturally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement.

The issuance of the 12-year bond with a coupon of 4.975 attracted 188 investors from around the world, of whom 21% are new holders of Uruguayan debt. Total demand for the bond was US$ 3.96 billions, exceeding the US$ 1.5 billions Uruguay issued.

The SLB Framework adopted by Uruguay set as targets (i) the reduction of GHG emissions and (ii) the conservation of the country’s native forest area.

Among other LAC countries, also Peru and Mexico are committing to significant ESG sovereign issuance, while others comparable countries, such as Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, and Panama, are still a step behind.

Despite the slower pace of Peru’s market of green, social, and sustainable bonds expansion, there have been and there are significant movements to leverage sustainable finance in the country. Indeed, Peru is Latin America’s sustainable finance pioneer: the Peruvian company Energía Eólica S.A. was the first green bond issuer in the region in December 2014 with a 20-year, US$ 204 millions deal to finance two wind energy projects.

Then, Peru successfully issued three thematic sovereign bonds in November 2021. The deals are part of the Government’s strategy in response to the pandemic and aim to address the economic, environmental, and social challenges of the country.

The government began with two sustainability bonds, one with 12-year maturity worth US$ 2.3 billion with a coupon of 3.000 and a US$ 1 billion 50-year maturity with a coupon of 3.600. Two weeks later, Peru issued a 15-year EUR 1 billion social bond with a coupon of 4.846. All deals were at least two times oversubscribed and attracted international investors.

The Sustainable Framework adopted by Peru establishes the eligible categories to refinance 2021- 2022 government expenditures, which include: “social housing, education, and health services; financial support to MSMEs and vulnerable people; green buildings, renewable energy, energy efficiency, low-carbon transport, water infrastructure, sustainable management of natural resources, agriculture, and waste management.” [3]

Similarly, Mexico is increasing its green, social, and sustainable bond issuances in recent years too: with a few in 2020 and 2021, 2022 is a record year with the issuance of several sustainability bonds (with maturity ranging from 3 to 20 years with coupons varying from 1.000 for the 3-years coupon bond to 4.875 for the 11-year one). According to experts, these bonds can be key to a sustainable transition in the financial sector and securities markets of the country. However, the availability, transparency, and quality of information on the bonds are key to this scope.

Bond Pricing and Greenium

For issuers, SLBs are most attractive because they allow access to a lower cost of capital in exchange for pursuing sustainability goals. In comparison to other products such as green bonds, SLBs do not require the funds to be used towards specific projects, just that the issuer achieves its stated goals (KPIs) by the observation date. Otherwise, the issuer most commonly faces a “step-up” in the coupon – typically 25 bps – paid until maturity.

In some cases, there have been arguments made for the efficacy of a “step-down” mechanism wherein investors agree to an even lower yield if the sustainability goal is realized. Currently, Uruguay has issued a SLB with a two-way pricing structure that would involve both a 15bps step-down in coupon if it exceeds its targets and a 15 bps step-up if it misses them. Thus far, the “step-up” condition is the most common that issuers employ since most investors find the step-down mechanism much more unfavorable. However, Anjuli Pandit, head of sustainable bonds for EMEA and the Americas at HSBC says that for the sovereign-market, a two-way pricing model is essential for mitigating ESG risks and potential credit risks.

The incentive for the “step-up” pricing structure is that investors are willing to accept a lower yield in exchange for the potential impact a company will make or an increase in coupon in the case of failure. On the other hand, companies are also incentivized to pursue such goals, which usually carry higher and longer-term investment costs, at a more reasonable price. After issuing bonds, some companies also saw an increase in their share price and investor confidence in their dedication to ESG, further incentivizing the issuance of ESG bonds like SLBs.

With this pricing structure, a couple key considerations present themselves. With the willingness of investors to pay a higher price/accept a lower yield, there has been speculation as to whether “greenium” exists. Greenium is defined as the issuer’s savings from issuing a green-oriented product as compared to its vanilla counterpart. Theoretically, because the bonds have similar liquidity, risk and maturity profiles, they should also guarantee similar yields regardless of their ESG commitment. Recently, the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) examined 37 sustainably linked bonds issued in 2021 and 2022, it found that 14 achieved a greenium. The Climate Bonds Initiative used criteria to match the SLBs with vanilla bonds with shorter and longer duration to reconstruct a yield curve. A bond is considered to have greenium if it is priced within its own yield curve – meaning that when a yield curve is reconstructed using similar non-sustainable bonds, the yield for the SLB is lower.

These findings are consistent with conclusions from an earlier study conducted by Danilo Liberati and Giuseppe Marinelli (2021). Their study shows significant evidence of a greenium and deconstructs the ESG bond market by sector and issuer. For non-financial USD denominated ESG bonds, they show an average negative spread of 9 bps between ESG and non-ESG bonds.

In some cases, there have been arguments made for the efficacy of a “step-down” mechanism wherein investors agree to an even lower yield if the sustainability goal is realized. Currently, Uruguay has issued a SLB with a two-way pricing structure that would involve both a 15bps step-down in coupon if it exceeds its targets and a 15 bps step-up if it misses them. Thus far, the “step-up” condition is the most common that issuers employ since most investors find the step-down mechanism much more unfavorable. However, Anjuli Pandit, head of sustainable bonds for EMEA and the Americas at HSBC says that for the sovereign-market, a two-way pricing model is essential for mitigating ESG risks and potential credit risks.

The incentive for the “step-up” pricing structure is that investors are willing to accept a lower yield in exchange for the potential impact a company will make or an increase in coupon in the case of failure. On the other hand, companies are also incentivized to pursue such goals, which usually carry higher and longer-term investment costs, at a more reasonable price. After issuing bonds, some companies also saw an increase in their share price and investor confidence in their dedication to ESG, further incentivizing the issuance of ESG bonds like SLBs.

With this pricing structure, a couple key considerations present themselves. With the willingness of investors to pay a higher price/accept a lower yield, there has been speculation as to whether “greenium” exists. Greenium is defined as the issuer’s savings from issuing a green-oriented product as compared to its vanilla counterpart. Theoretically, because the bonds have similar liquidity, risk and maturity profiles, they should also guarantee similar yields regardless of their ESG commitment. Recently, the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) examined 37 sustainably linked bonds issued in 2021 and 2022, it found that 14 achieved a greenium. The Climate Bonds Initiative used criteria to match the SLBs with vanilla bonds with shorter and longer duration to reconstruct a yield curve. A bond is considered to have greenium if it is priced within its own yield curve – meaning that when a yield curve is reconstructed using similar non-sustainable bonds, the yield for the SLB is lower.

These findings are consistent with conclusions from an earlier study conducted by Danilo Liberati and Giuseppe Marinelli (2021). Their study shows significant evidence of a greenium and deconstructs the ESG bond market by sector and issuer. For non-financial USD denominated ESG bonds, they show an average negative spread of 9 bps between ESG and non-ESG bonds.

Source: Liberati and Marinelli (2021)

Another study conducted by Kapraun and Scheins (2019) also found evidence of greenium and went even further to hypothesize that variability in the size of the greenium is dependent on the credibility of the issuer itself: investors were willing to pay a higher greenium if the issuer was considered to be more trustworthy. A key finding for this study was that bonds issued by governments were considered to be more credible than those issued by corporations and thus have more greenium. For example, in the case of the SLBs discussed in this article issued by the Chilean and Uruguayan governments, it is expected that those bonds may have an even higher greenium than ones issued by private corporations.

Such results greatly contrast those of another notable study conducted by Larcker and Watts (2019) who claim that differences in yields are negligible and that greenium is nonexistent. Their argument hinges on the idea that investors are not willing to pay a premium for a thematic bond/the green label. However, a limitation of this study is that it analyzed only U.S. municipal bonds, and given findings from other studies, it is evident that in many cases, where larger and other sample types were used, greenium can be found.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) offers a few arguments in favor of greenium-pricing. Firstly, greenium allows cheaper access to financing to pursue credit-positive sustainable goals, which ultimately reduce the risk of the issue and therefore justify a lower yield. The UNDP also argues that the demand shown for thematic debt issuance inherently increases the price (and lowers yields) for investors, and finally, given investor’s motivations for creating a greener portfolio, they should be willing to pay a premium for the label itself.

Another paper written by Mielnik and Erlandsson (2022) argues that while a premium should exist, how the step-up and premium is priced should depend on the optionality or ambition of the KPIs. They argue that by attaching relative probabilities to whether a company can meet its goals, one can more accurately price how much the premium and step-up should be in order to incentivize the company to pursue its goals. While this approach is not currently used in practice, it does suggest that issuers re-evaluate their pricing approach and to use a more data-driven methodology when pricing their bonds.

It should be noted that this area of research is still relatively nascent and leaves much to be explored. The Inter-American Development Bank put out a call to researchers earlier this year to present their papers on the pricing of green bonds and SLBs at a virtual conference to take place later this month.

Such results greatly contrast those of another notable study conducted by Larcker and Watts (2019) who claim that differences in yields are negligible and that greenium is nonexistent. Their argument hinges on the idea that investors are not willing to pay a premium for a thematic bond/the green label. However, a limitation of this study is that it analyzed only U.S. municipal bonds, and given findings from other studies, it is evident that in many cases, where larger and other sample types were used, greenium can be found.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) offers a few arguments in favor of greenium-pricing. Firstly, greenium allows cheaper access to financing to pursue credit-positive sustainable goals, which ultimately reduce the risk of the issue and therefore justify a lower yield. The UNDP also argues that the demand shown for thematic debt issuance inherently increases the price (and lowers yields) for investors, and finally, given investor’s motivations for creating a greener portfolio, they should be willing to pay a premium for the label itself.

Another paper written by Mielnik and Erlandsson (2022) argues that while a premium should exist, how the step-up and premium is priced should depend on the optionality or ambition of the KPIs. They argue that by attaching relative probabilities to whether a company can meet its goals, one can more accurately price how much the premium and step-up should be in order to incentivize the company to pursue its goals. While this approach is not currently used in practice, it does suggest that issuers re-evaluate their pricing approach and to use a more data-driven methodology when pricing their bonds.

It should be noted that this area of research is still relatively nascent and leaves much to be explored. The Inter-American Development Bank put out a call to researchers earlier this year to present their papers on the pricing of green bonds and SLBs at a virtual conference to take place later this month.

Sustainability Impact of Sustainability-Linked Bonds

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing has probably been the most widely discussed topic in the global bond market for the last couple of years. The effects of the Covid-19 pandemic have brought the problems facing us and our planet more sharply into focus.

During the latest UN Climate Change Conference of Parties (Cop26) carried out at the beginning of November in Glasgow, Mario Draghi underlined that “we need a quantum leap on the fight against climate change” and that “we must strengthen our efforts in the realm of climate finance”. Finance is the transmission belt to channel resources towards areas and sectors that will contribute to achieving the established objectives.

Aligning the corporate and governmental bond market with sustainability goals is critical for moving the financial services sector toward net-zero (i.e., carbon neutrality).

During the latest UN Climate Change Conference of Parties (Cop26) carried out at the beginning of November in Glasgow, Mario Draghi underlined that “we need a quantum leap on the fight against climate change” and that “we must strengthen our efforts in the realm of climate finance”. Finance is the transmission belt to channel resources towards areas and sectors that will contribute to achieving the established objectives.

Aligning the corporate and governmental bond market with sustainability goals is critical for moving the financial services sector toward net-zero (i.e., carbon neutrality).

SLBs in Latin America

In recent years, Latin American bond markets have experienced a significant boost associated with greater depth and transparency in terms of financial and non-financial information (environmental and social) provided by companies. In fact, changes in the legal frameworks that govern the operation of corporate governance have contributed to making investment decisions more accountable, together with the increasing importance of disclosure of information on the financial climate impacts of investment projects brought by the surge of GSSS bond issuance.

The ESG bond market in the region was initially supported by sovereign issuers and then followed by financial institutions.

So far, the most common ESG objective or target of the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region’s SLB issuances has been reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (70% of bonds’ KPI). The second most used KPI was water management, which was present in 23% of the SLB issuances. Other less common ESG objectives include an increase in the number of women in leadership positions, waste reduction, and an increase in renewable energy.

Although SLBs are newer than use-of-proceeds bonds, issuance levels in LAC have been very strong during 2021, as these instruments allow issuers to access investors and banks with a sustainability focus, while maintaining the flexibility of allocating the proceeds to general corporate purposes.

In fact, SLBs make up a higher proportion of the green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked bond (GSSSB) market in Latin America than in any other region globally, and sovereign issuances in the region continue to attract attention from international investors.

GSSSB has proven to be a prominent contributor to total bond issuance in Latin America, accounting for 35% of total issuance in the region in the first half of 2022.

The ESG bond market in the region was initially supported by sovereign issuers and then followed by financial institutions.

So far, the most common ESG objective or target of the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region’s SLB issuances has been reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (70% of bonds’ KPI). The second most used KPI was water management, which was present in 23% of the SLB issuances. Other less common ESG objectives include an increase in the number of women in leadership positions, waste reduction, and an increase in renewable energy.

Although SLBs are newer than use-of-proceeds bonds, issuance levels in LAC have been very strong during 2021, as these instruments allow issuers to access investors and banks with a sustainability focus, while maintaining the flexibility of allocating the proceeds to general corporate purposes.

In fact, SLBs make up a higher proportion of the green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked bond (GSSSB) market in Latin America than in any other region globally, and sovereign issuances in the region continue to attract attention from international investors.

GSSSB has proven to be a prominent contributor to total bond issuance in Latin America, accounting for 35% of total issuance in the region in the first half of 2022.

Sustainability Conditions of SLBs

Published by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles are voluntary process guidelines that outline best practices for financial instruments and promote integrity in the development of the Sustainability-Linked Bond market by clarifying the approach for issuance of an SLB. The SLBP are intended for broad use by the market: they provide issuers with guidance on the key components of a credible and ambitious SLB and they aid investors by promoting accountability of issuers in their sustainability strategy and availability of information necessary to evaluate their SLB investments. The SLBP emphasize the recommended and necessary transparency, accuracy, and integrity of the information that will be disclosed and reported by issuers to stakeholders.

The SLBP have five core components:

1. Selection of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

2. Calibration of Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs)

3. Bond characteristics

4. Reporting

5. Verification

By looking more in detail at the first two components, as for the selection of KPIs, it is fundamental to understand that the credibility of the Sustainability Linked Bond market will rest on the selection of those. It is important to the success of this instrument to avoid the proliferation of KPIs that are not credible.

The KPIs should be:

• relevant, core, and material to the issuer’s overall business, and of high strategic significance to the issuer’s current and/ or future operations;

• measurable or quantifiable on a consistent methodological basis;

• externally verifiable; and

• able to be benchmarked, i.e., as much as possible using an external reference or definitions to facilitate the assessment of the SPT’s level of ambition.

Issuers should communicate clearly to investors the rationale and process according to which the KPI(s) have been selected and how the KPI(s) fit into their sustainability strategy, defining the applicable scope or perimeter (e.g., the percentage of the issuer’s total emissions to which the target is applicable), as well as the calculation methodology.

SPTs must be set in good faith and the issuer should disclose strategic information that may decisively impact the achievement of the SPTs. The SPTs should be ambitious, and where possible, they should be compared to a benchmark or an external reference. They need also to be consistent with the issuers’ overall strategic sustainability and be determined on a predefined timeline, set before (or concurrently with) the issuance of the bond.

The SLBP have five core components:

1. Selection of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

2. Calibration of Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs)

3. Bond characteristics

4. Reporting

5. Verification

By looking more in detail at the first two components, as for the selection of KPIs, it is fundamental to understand that the credibility of the Sustainability Linked Bond market will rest on the selection of those. It is important to the success of this instrument to avoid the proliferation of KPIs that are not credible.

The KPIs should be:

• relevant, core, and material to the issuer’s overall business, and of high strategic significance to the issuer’s current and/ or future operations;

• measurable or quantifiable on a consistent methodological basis;

• externally verifiable; and

• able to be benchmarked, i.e., as much as possible using an external reference or definitions to facilitate the assessment of the SPT’s level of ambition.

Issuers should communicate clearly to investors the rationale and process according to which the KPI(s) have been selected and how the KPI(s) fit into their sustainability strategy, defining the applicable scope or perimeter (e.g., the percentage of the issuer’s total emissions to which the target is applicable), as well as the calculation methodology.

SPTs must be set in good faith and the issuer should disclose strategic information that may decisively impact the achievement of the SPTs. The SPTs should be ambitious, and where possible, they should be compared to a benchmark or an external reference. They need also to be consistent with the issuers’ overall strategic sustainability and be determined on a predefined timeline, set before (or concurrently with) the issuance of the bond.

Comparing Sustainability Links in Latin American SLBs

Uruguay

Uruguay made its market debut in the format in October 2022, through a ground-breaking deal – a $1 billion note maturing in 2034 – that will link the cost of financing to Uruguay’s nationally determined contributions and the coverage of native forests in the country. In addition, the issuances will be subject to a one-time coupon step-down in the case Uruguay outperforms its NDCs. The framework’s innovation arises from its combination of step-up and step-down mechanisms.

The Minister of Economy and Finance of Uruguay, Azucena Arbeleche, stated: “First of all, to put this in context I think we have to bear in mind that Uruguay is at a turning point when it comes to fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, and an economic recovery is underway. Our goal is for this recovery to be inclusive and sustainable. That is to say, we can combine growth and the creation of jobs with an improvement in the population's living conditions. This goes hand in hand with investments that have a positive, measurable, and verifiable impact on social and environmental indicators”.

The bond will be linked to Uruguay’s previously established environmental target, such as nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement, which the country submitted in 2017 and in which it proposes per-gas carbon intensity reduction targets for three specific gases: carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane, with reductions of 24%, 48%, and 57% respectively by 2025, on an unconditional basis.

By looking at Sustainalytics’ evaluation, they are of the opinion that Uruguay’s Sovereign Sustainability-Linked Bond (SSLB) Framework aligns with the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles 2020 and that the two KPIs chosen, 50% reduction of aggregate GHG emissions per real GDP unit compared to the year 1990 and maintenance of 100% of the Native Forest area compared to the 2012 year, are strong.

The Minister of Economy and Finance of Uruguay, Azucena Arbeleche, stated: “First of all, to put this in context I think we have to bear in mind that Uruguay is at a turning point when it comes to fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, and an economic recovery is underway. Our goal is for this recovery to be inclusive and sustainable. That is to say, we can combine growth and the creation of jobs with an improvement in the population's living conditions. This goes hand in hand with investments that have a positive, measurable, and verifiable impact on social and environmental indicators”.

The bond will be linked to Uruguay’s previously established environmental target, such as nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement, which the country submitted in 2017 and in which it proposes per-gas carbon intensity reduction targets for three specific gases: carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane, with reductions of 24%, 48%, and 57% respectively by 2025, on an unconditional basis.

By looking at Sustainalytics’ evaluation, they are of the opinion that Uruguay’s Sovereign Sustainability-Linked Bond (SSLB) Framework aligns with the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles 2020 and that the two KPIs chosen, 50% reduction of aggregate GHG emissions per real GDP unit compared to the year 1990 and maintenance of 100% of the Native Forest area compared to the 2012 year, are strong.

Chile

In March 2022, the Republic of Chile priced the first-ever Sovereign Sustainability-Linked Bond (SSLB). This $2 billion 20-year SLB was more than 4 times oversubscribed.

With this issuance, Chile aimed to embed green and financial incentives across several political cycles, while mitigating some of the limitations of existing sovereign green, social and sustainability instruments.

The two KPIs associated with the bond are an absolute reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (from 107.7mt/pa in 2018 to 95mt/pa by 2030) and an increase in renewable energy generation (60% from renewables by 2032). Sustainalytics, which provided the second party opinion rated the targets as ‘very strong’ and ‘strong’ respectively.

As for the Calibration of Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs), Sustainalytics considers the SPTs to be aligned with Chile’s sustainability strategy and really ambitious.

With this issuance, Chile aimed to embed green and financial incentives across several political cycles, while mitigating some of the limitations of existing sovereign green, social and sustainability instruments.

The two KPIs associated with the bond are an absolute reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (from 107.7mt/pa in 2018 to 95mt/pa by 2030) and an increase in renewable energy generation (60% from renewables by 2032). Sustainalytics, which provided the second party opinion rated the targets as ‘very strong’ and ‘strong’ respectively.

As for the Calibration of Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs), Sustainalytics considers the SPTs to be aligned with Chile’s sustainability strategy and really ambitious.

Mexico

The government of the State of Mexico placed a sustainable bond for an amount in local currency equivalent to about 150 million dollars on the Mexican Stock Exchange (BMV) on the 27 of June, with a 15-year term.

The resources obtained will be used to finance clean transport programs, support people in vulnerable situations, as well as actions that contribute to access to essential services.

Among the projects it will seek to finance is the Naucalpan cable car, which runs on solar energy and will prevent the emissions of 17,000 tons of CO2 per year, as well as the Chalco-Santa Martha trolleybus route.

In social matters, it will allocate resources for actions to prevent and care for women victims of violence, as well as teenage pregnancy.

Sustainalytics is of the opinion that the Estado de Mexico Sustainability Bond Framework is credible and impactful, and aligns with the Sustainability Bond Guidelines 2021, Green Bond Principles 2021, and Social Bond Principles 2021. Sustainalytics considers that investments in the eligible categories will contribute to positive environmental or social impacts and advance the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The resources obtained will be used to finance clean transport programs, support people in vulnerable situations, as well as actions that contribute to access to essential services.

Among the projects it will seek to finance is the Naucalpan cable car, which runs on solar energy and will prevent the emissions of 17,000 tons of CO2 per year, as well as the Chalco-Santa Martha trolleybus route.

In social matters, it will allocate resources for actions to prevent and care for women victims of violence, as well as teenage pregnancy.

Sustainalytics is of the opinion that the Estado de Mexico Sustainability Bond Framework is credible and impactful, and aligns with the Sustainability Bond Guidelines 2021, Green Bond Principles 2021, and Social Bond Principles 2021. Sustainalytics considers that investments in the eligible categories will contribute to positive environmental or social impacts and advance the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Conclusion

Sustainable development must undoubtedly be part of political and economic decisions. Latin America’s evolution and growth in the field of sustainable finance is particularly significant. Issuers of green, social and sustainable bonds are forward thinking. Their issuances not only contribute to the fight against climate change but also inclusive and sustainable growth. Latin America is an emerging leader in the sustainability-linked bond market, and sovereign issuances will play a major role in attracting attention from international investors, presenting a unique opportunity for the region to establish a central position in fixed-income markets.

Written by Francesco Doga, Matilde Oliana and Ava Trahan

Sources

- Azimut Direct (2021, Nov 4). Sustainability-linked bond: cosa sono e come funzionano.

https://azimutdirect.com/it/blog/green-finance/sustainability-linked-bond-cosa-sono-e-come-funzionano - BNP PARIBAS (2022), Chile sets a trend with first sovereign sustainability-linked bond, https://cib.bnpparibas/chile-sets-a-trend-with-first-sovereign-sustainability-linked-bond/

- Bouzidi D., Mills S. (2022, April). Sovereign Sustainability-Linked Bonds: Chile Sets A High Bar. Global Green Finance Index (GGFI) by Z/Yen.

https://www.longfinance.net/media/documents/policy_performance_bond_supplement_1.3_SM_220506.pdf - Climate Bonds Initiative (2021), Climate Bonds Initiative releases its latest report for Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) market - Green Bonds in the region doubled in less than two years https://www.climatebonds.net/files/releases/climate_bonds_initiative_media_release_lac_sotm_september2021.docx_0.pdf

- Climate Bonds Initiative (2021), Peru Sustainable Finance - State of the Market 2022, https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_peru_sotm_2021_03d.pdf

- d’Incau, F., Mercusa, N., Wijeweera, K., & Zoltani, T. (2022, April 25). Identifying the 'greenium': United Nations Development Programme. UNDP. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.undp.org/blog/identifying-greenium

- ECLAC (2022), Issuance of Sustainability-linked Bonds by Latin American Companies in International Markets Grows Exponentially in 2021, https://www.cepal.org/en/news/issuance-sustainability-linked-bonds-latin-american-companies-international-markets-grows

- Eggerstedt, S. (2021, May 20). Schroders plc. What are sustainability-linked bonds and how do they work? Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.schroders.com/en/za/intermediary/insights/markets/what-are-sustainability-linked-bonds-and-how-do-they-work/

- GFL (2022), Chile becomes the first country in the world to issue a Sustainability Linked Bond, https://greenfinancelac.org/resources/news/chile-becomes-the-first-country-in-the-world-to-issue-a-sustainability-bond/

- GFL (2022), New Framework for potential sustainable bond issuance in Uruguay, https://greenfinancelac.org/resources/news/new-framework-for-potential-sustainable-bond-issuance-in-uruguay/

- GFL, Green Finance for Latin America (2022, May 12). The State of Mexico issues its first sustainable bond.

https://greenfinancelac.org/resources/news/the-state-of-mexico-issues-its-first-sustainable-bond/ - IDB (2022), Uruguay Issues Global Sustainability-Linked Bond, with IDB Support, https://www.iadb.org/en/news/uruguay-issues-global-sustainability-linked-bond-idb-support

- International Trade Administration (2022, Sep 30). Chile – Country Commercial Guide: Energy.

https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/chile-energy - Jones, L. (2021, September 16). Greenium remains visible in latest pricing study. Climate Bonds Initiative. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.climatebonds.net/2021/09/greenium-remains-visible-latest-pricing-study

- Kapraun, J., & Scheins, C. (2019). (In)-Credibly Green: Which Bonds Trade at a Green Bond Premium? Paris December 2019 Finance Meeting. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332203008_In-Credibly_Green_Which_Bonds_Trade_at_a_Green_Bond_Premium

- Larcker, D., & Watts, E. (2019, February 12). Where's the Greenium? Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University Working Paper No. 239, Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 19-14, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Volume 69, Issues 2–3, April–May 2020, 101312. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3333847

- Lazari N., Sugrue D. (2022, Nov 9). Latin America Green, Social, Sustainability, And Sustainability-Linked Bonds 2022. ESG Research.

https://www.spglobal.com/_assets/documents/ratings/research/101568893.pdf - Liberati, D.,& Marinelli, G. (2021, November 25). Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Green Bonds (but were afraid to ask) Bank of Italy Occasional Paper No. 654. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.bis.org/ifc/publ/ifcb56_19.pdf

- Mielnik, S., & Erlandsson, U. (2022, March 18). An option pricing approach for sustainability-linked bonds. Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/946d6aac-e6cc-430a-8898-520cf90f5d3e/AFII%20SLB%20option%20pricing%20approach.pdf

- Ministerio de Hacienda, Gobierno de Chile, Sustainability-linked bonds https://www.hacienda.cl/english/work-areas/international-finance/public-debt-office/esg-bonds/sustainability-linked-bonds

- Ministry of Economy and Finance of Uruguay (2022, March 12). SSLB Framework. Open Data Source [Dataset].

http://sslburuguay.mef.gub.uy/#:~:text=SSLB%20Framework&text=The%20Framework%20describes%20Uruguay's%20sustainable,native%20forests%20in%20the%20country. - Murphy D. (2022, Nov 11). What are sustainability-linked bonds and how can they support the net-zero transition? World Economic Forum.

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/11/cop27-sustainability-linked-bonds-net-zero-transition/ - Sustainalytics (2022, February). Government of Chile Sustainability-Linked Bond Framework Second Party Opinion (2022).

https://www.sustainalytics.com/corporate-solutions/sustainable-finance-and-lending/published-projects/project/government-of-chile/government-of-chile-sustainability-linked-bond-framework-second-party-opinion-(2022)/government-of-chile-sustainability-linked-bond-framework-second-party-opinion-(2022) - Sustainalytics (2022, May). Estado de Mexico Sustainability Bond Framework Second Party Opinion (2022) (English).

https://www.sustainalytics.com/corporate-solutions/sustainable-finance-and-lending/published-projects/project/estado-de-mexico/estado-de-mexico-sustainability-bond-framework-second-party-opinion-(2022)-(english)/estado-de-mexico-sustainability-bond-framework-second-party-opinion-(2022)-(english) - Sustainalytics (2022, September). Uruguay’s Sovereign Sustainability-Linked Bond Framework Second-Party Opinion (2022).

https://www.sustainalytics.com/corporate-solutions/sustainable-finance-and-lending/published-projects/project/oriental-republic-of-uruguay/uruguay-s-sovereign-sustainability-linked-bond-framework-second-party-opinion-(2022)/uruguay-s-sovereign-sustainability-linked-bond-framework-second-party-opinion-(2022) - Tejada (2021), Sustainability-linked bonds: Great news for sustainable financing in Latin America”, BBVA, https://www.bbva.com/en/sustainability/sustainability-linked-bonds-great-news-for-sustainable-financing-in-latin-america/

- Walsh, T. (2022, August 5). Uruguay exploring controversial two-way SLB pricing. IFRe. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.ifre.com/story/3458615/uruguay-exploring-controversial-two-way-slb-pricing-jmdxsljfjf

[1] Ministerio de Hacienda, Gobierno de Chile, Sustainability-linked bonds https://www.hacienda.cl/english/work-areas/international-finance/public-debt-office/esg-bonds/sustainability-linked-bonds

[2] BNP PARIBAS (2022), Chile sets a trend with first sovereign sustainability-linked bond, BNP PARIBAS, https://cib.bnpparibas/chile-sets-a-trend-with-first-sovereign-sustainability-linked-bond/

[3] Climate Bonds Initiative (2021), Peru Sustainable Finance - State of the Market 2022, Climate Bonds Initiative, https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_peru_sotm_2021_03d.pdf

[2] BNP PARIBAS (2022), Chile sets a trend with first sovereign sustainability-linked bond, BNP PARIBAS, https://cib.bnpparibas/chile-sets-a-trend-with-first-sovereign-sustainability-linked-bond/

[3] Climate Bonds Initiative (2021), Peru Sustainable Finance - State of the Market 2022, Climate Bonds Initiative, https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_peru_sotm_2021_03d.pdf