Introduction

It was February, 22nd when Atieva Inc. (dba, Lucid Motors) and Churchill Capital Corp IV announced that they had entered into a definitive merger agreement. CCIV, a special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC), and Lucid Motors, a start-up that is setting new standards for sustainable mobility with its advanced luxury EVs, are combining at a transaction equity value of $11.75bn and an implied pro forma equity valuation of $24bn.

Lucid’s mission is to stimulate the adoption of sustainable emission-free transportation by creating game-changer luxury EVs that pivoted on the human experience. The transaction will provide additional growth capital as the Silicon Valley-headquartered start-up brings its Lucid Air luxury electric sedan to market and expands rapidly to offer a broad range of EV products that, thanks to Lucid’s proprietary electric powertrain technology, will allow the company to become even more competitive in the Tesla-monopolized electric vehicle market.

Brief introduction about SPACs

During the last couple of years, Special-Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPAC) have been extremely successful and are now in fashion more than ever: born almost 30 years ago, SPACs have gained much popularity only very recently and 2020 has witnessed more than fourfold as many SPAC IPOs with respect to the previous year, with a total of $75bn of investment.

SPACs often go also under other names such as blank-check companies and shell companies: the former refers to the idea that investors putting money into these companies typically have no prior idea about what type of business they are investing in, while the latter to the fact that SPACs naturally have no commercial operations when launched.

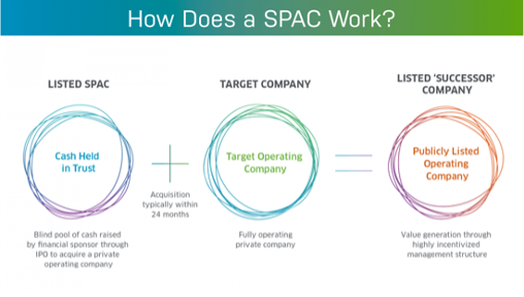

A SPAC is an alternative to an IPO and exists purposefully to raise capital to acquire a target private company and then take it public. It is a new original way to access capital markets through an IPO, which it undertakes on behalf of the private company that it will acquire. To contribute to the fund can be both retail and institutional investors and their stake in the combined company depends on the valuation of the target private company and the size of the investment that the SPAC makes in it.

The chief advantages of a SPAC are that its structure allows companies to provide forward-looking projections and that its creation allows companies to be publicly traded much faster than in a formal IPO process. However, even though they pop when the announcement of a combination is made, they usually cannot hold a candle to the long-term performance of traditional IPOs. Indeed, when Renaissance Capital looked at the 813 SPAC IPOs from January 2015 through September 2020, it noticed that the median post-merger return of the 93 SPACs that was able to complete a combination was -29.1%, while the average after-market return of traditional IPOs was 47.1%.

The founders of a SPAC are its "sponsors": they are typically highly experienced executives or fund managers who make the initial investment in the blank check company and then seek out potential investors to further fund the project. Usually, the sponsors keep a 20% stake after the SPAC IPO (which is far more than what their first investment amounted to, which is usually around 3%), ending up with significant holding in the company born from the merge of the private and the blank check company. Since sponsors are prohibited from identifying a target private company before launching the SPAC, people ground their investment in SPAC IPOs only on the reputation and experience of their sponsors: the more deals a sponsor has completed, the more confident prospective investors become. Some serial sponsors who have launched several successful SPACs are Michael Klein, Chamath Palihapitiya, and Bill Foley.

Usually, SPAC priced their IPO at $10 per share and, while looking for the right target company, the money raised is kept in a trust account and no salary is paid to the member of the management board. Also, SPACs are required to merge with a private company whose fair market value is at least 80% of the funds held in trust. Closely connected to SPACs are PIPE deals: standing for Private Investment in Public Equity, they involve selling shares of a public company in a private arrangement with a selected investor or group of investors. The PIPE investors get a large equity stake, and the SPAC investors get stock in the acquired company, which becomes the publicly traded entity. This way of raising additional capital is usually pursued in case the cost to close the merger transaction with the target company exceeds the funds that a SPAC has in its trust account.

Finally, a SPAC is required to close the merge within three years of its initial IPO. Nevertheless, SPAC investors typically expect a deal to be closed within two years. When it is not possible to close the deal within the established period, the investors get back their money and the special-purpose acquisition company dissolves. When this occurs, SPAC sponsors lose the money they had invested to found the blank check company. Similarly, a SPAC may also fail in case the investors have no longer faith in the project and decide to withdraw their money, leaving it with little cash to complete a deal. In such cases, a SPAC can address this risk by raising capital through PIPE arrangements.

It was February, 22nd when Atieva Inc. (dba, Lucid Motors) and Churchill Capital Corp IV announced that they had entered into a definitive merger agreement. CCIV, a special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC), and Lucid Motors, a start-up that is setting new standards for sustainable mobility with its advanced luxury EVs, are combining at a transaction equity value of $11.75bn and an implied pro forma equity valuation of $24bn.

Lucid’s mission is to stimulate the adoption of sustainable emission-free transportation by creating game-changer luxury EVs that pivoted on the human experience. The transaction will provide additional growth capital as the Silicon Valley-headquartered start-up brings its Lucid Air luxury electric sedan to market and expands rapidly to offer a broad range of EV products that, thanks to Lucid’s proprietary electric powertrain technology, will allow the company to become even more competitive in the Tesla-monopolized electric vehicle market.

Brief introduction about SPACs

During the last couple of years, Special-Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPAC) have been extremely successful and are now in fashion more than ever: born almost 30 years ago, SPACs have gained much popularity only very recently and 2020 has witnessed more than fourfold as many SPAC IPOs with respect to the previous year, with a total of $75bn of investment.

SPACs often go also under other names such as blank-check companies and shell companies: the former refers to the idea that investors putting money into these companies typically have no prior idea about what type of business they are investing in, while the latter to the fact that SPACs naturally have no commercial operations when launched.

A SPAC is an alternative to an IPO and exists purposefully to raise capital to acquire a target private company and then take it public. It is a new original way to access capital markets through an IPO, which it undertakes on behalf of the private company that it will acquire. To contribute to the fund can be both retail and institutional investors and their stake in the combined company depends on the valuation of the target private company and the size of the investment that the SPAC makes in it.

The chief advantages of a SPAC are that its structure allows companies to provide forward-looking projections and that its creation allows companies to be publicly traded much faster than in a formal IPO process. However, even though they pop when the announcement of a combination is made, they usually cannot hold a candle to the long-term performance of traditional IPOs. Indeed, when Renaissance Capital looked at the 813 SPAC IPOs from January 2015 through September 2020, it noticed that the median post-merger return of the 93 SPACs that was able to complete a combination was -29.1%, while the average after-market return of traditional IPOs was 47.1%.

The founders of a SPAC are its "sponsors": they are typically highly experienced executives or fund managers who make the initial investment in the blank check company and then seek out potential investors to further fund the project. Usually, the sponsors keep a 20% stake after the SPAC IPO (which is far more than what their first investment amounted to, which is usually around 3%), ending up with significant holding in the company born from the merge of the private and the blank check company. Since sponsors are prohibited from identifying a target private company before launching the SPAC, people ground their investment in SPAC IPOs only on the reputation and experience of their sponsors: the more deals a sponsor has completed, the more confident prospective investors become. Some serial sponsors who have launched several successful SPACs are Michael Klein, Chamath Palihapitiya, and Bill Foley.

Usually, SPAC priced their IPO at $10 per share and, while looking for the right target company, the money raised is kept in a trust account and no salary is paid to the member of the management board. Also, SPACs are required to merge with a private company whose fair market value is at least 80% of the funds held in trust. Closely connected to SPACs are PIPE deals: standing for Private Investment in Public Equity, they involve selling shares of a public company in a private arrangement with a selected investor or group of investors. The PIPE investors get a large equity stake, and the SPAC investors get stock in the acquired company, which becomes the publicly traded entity. This way of raising additional capital is usually pursued in case the cost to close the merger transaction with the target company exceeds the funds that a SPAC has in its trust account.

Finally, a SPAC is required to close the merge within three years of its initial IPO. Nevertheless, SPAC investors typically expect a deal to be closed within two years. When it is not possible to close the deal within the established period, the investors get back their money and the special-purpose acquisition company dissolves. When this occurs, SPAC sponsors lose the money they had invested to found the blank check company. Similarly, a SPAC may also fail in case the investors have no longer faith in the project and decide to withdraw their money, leaving it with little cash to complete a deal. In such cases, a SPAC can address this risk by raising capital through PIPE arrangements.

About CCIV and Lucid Motors

Churchill Capital IV is the fourth special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC) that was founded by former Vice Chairman at Citigroup and managing partner of M. Klein and Company, Michael Klein, in 2020. He was an early participant in the SPAC craze and he founded his first blank check company in 2018, which raised $690m and bought Clarivate Analytics in 2019.

CCIV was founded to identify companies that complement their expertise and execute a merger, capital stock exchange, asset acquisition, stock purchase, reorganization, or similar business combination with one or more of those companies. It sold 207 million units on July 30, 2020, at the traditional $10 per share offering price, raising more than $2bn.

Headquartered in the heart of Silicon Valley in Newark, California, Lucid is an automotive company that specializes in luxury electric cars and aims at creating an efficient, sustainable, autonomous, and intuitive source of mobility. Founded by Sheaupyng Lin, Sam Weng, and Bernard Tse (former Tesla executive) in 2007, from its very beginning it has benefitted enormously from California’s forward-thinking, innovation-centered business environment. Lucid Motors’ current CEO and CTO, Peter Rawlinson, served as the VP of Engineering at Tesla and was the Chief Engineer of Tesla’s Model S.

In addition to its in-house technological and manufacturing capabilities, Lucid has established strong relationships with core suppliers for key materials like battery cells, including a development and supply agreement with LG Chem. Currently, Lucid has 6 Studios open across the US and additional sites under construction. The company is now able to produce 34,000 vehicles per year, but thanks to the three phases of expansion planned for the incoming years it expects to reach 365,000 vehicles per year at scale very soon.

As a part of its vision, Lucid intends to leverage its technology portfolio and expertise in electrification to enable a broader societal transformation towards clean energy. Indeed, Lucid’s further projects include the development of products outside of the luxury vehicle market, including batteries with the ability to power homes and utility-scale devices, similar to Tesla’s Powerwall initiative.

Currently, there is also speculation around a potential future partnership between Lucid and Apple to produce luxury electric vehicles. Although Lucid would be the perfect fit for Apple's luxury branding, Apple will likely require a production capacity far above the levels Lucid will be able to meet within the next few years. Moreover, since Lucid is pursuing a vertical integration strategy, its production ramp-up will entail significant costs. Consequently, it is very difficult that the manufacturing partnerships between Apple and Lucid will materialize.

Rationale

Following the SPAC transaction, Lucid Motors will benefit from CCIV’s capital and be able to keep manufacturing in-house, maintaining simultaneously high quality and low costs.

After delays in the delivery of the company’s Lucid Air, CEO Peter Rawlinson now targets a start of production at Lucid’s new factory in Casa Grande, Arizona, in the early part of the second half of 2021. Indeed, Lucid will exploit the funds from the deal to increase its production capabilities and reach this goal. What is more, as the company keeps growing and aims at breaking into the EV market, one of its most challenging short-term priorities is going to be to establish itself as the luxury brand of the market, to differentiate from Tesla's mass-market strategy. Even though the transaction will bring about one of the major potential domestic competitors to Tesla, Rawlinson has repeatedly made it clear that Lucid Motors addresses solely the luxury EV market and there are no short-term projections of pursuing the same target as Tesla. Nevertheless, empowered by CCIV’s capital strength, Lucid will seek out to drive production costs down in the long-term and offer a broader range of vehicles, including also more affordable models to compete against Tesla. This is the same strategy that Elon Musk pursued when he first launched his premium Tesla Roadster in 2008.

While the SPAC merger with Churchill will provide capital for increased in-house manufacturing capability, further funding will be necessary to capture market share in the electric vehicle space and compete with already established players.

Over the next year, Lucid’s primary goal will be to focus on the production and delivery of its luxury EV Air, starting at $69,900, through heavy investment in R&D and an enhanced working base with 3,000 additional employees. The company expects deliveries of 20,000 vehicles in 2022, producing sales of $2.2 billion, and forecasts revenues of $5.5 billion in 2023, and $9.9 billion in 2024, imputing a CAGR of 36%. The luxury EV maker expects to become EBITDA-positive by 2024 and free cash flow–positive by 2025. By 2025 and 2026, the company hopes to realize gross margins of 22-23%, far less than the margins earned by leading technology companies. By 2026, it foresees its EBITDA rising to $2.9 billion, and expects a free cash flow of $1.5 billion.

Deal details

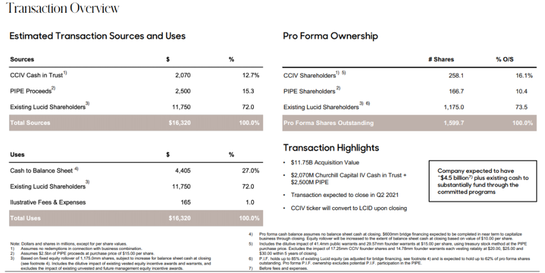

The total investment of approximately $4.6 billion is being funded by CCIV’s approximately $2.1bn in cash (assuming no redemptions by CCIV shareholders), which the blank check company raised in its July 2020 IPO, and a $2.5bn fully committed PIPE at $15.00 per share, a 50% premium to CCIV’s net asset value.

While in most cases PIPE investors buy at the IPO price at around $10 per share, the CCIV SPAC has broken the tradition of PIPEs. This transaction marks the largest private placement in public equity (PIPE) to date and it was led by the Public Investment Fund (PIF) of Saudi Arabia, which is also Lucid’s largest shareholder with $1bn invested back in 2018. The PIPE was joined also by funds and accounts managed by Fidelity Management & Research, BlackRock, Neuberger Berman, Franklin Templeton, Wellington Management, and Winslow Capital Management.

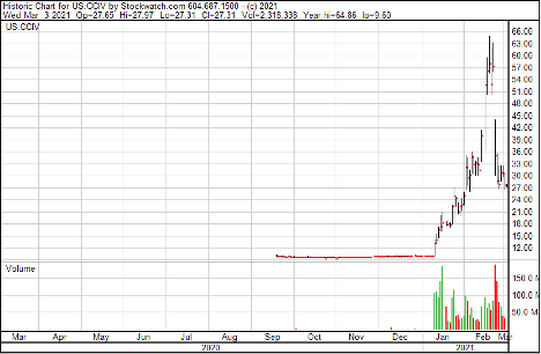

Following an article on Bloomberg on January 11 that suggested that the two companies were already in talks, as speculations rose and confidence grew that an agreement was to be reached, CCIV shares rose around 470% from the start of January to the stock’s peak of $58.05 on February 18, 2021. On February 23, the first day the market could react to the terms of the deal, CCIV shares collapsed by 39% to $35.21 and are currently trading around 64% lower than their peak at $21.35 (as of 3/29/21). This may be due to the “buy the rumor, sell the news” as is usually the case for highly anticipated deals such as Lucid’s, dissatisfaction with the structure of the deal, and disappointment in the delay of the delivery of the company’s Lucid Air.

The equity value of the deal was announced at $16.3bn, and existing Lucid shareholders will receive a value of $11.75bn, as consideration via issuance of 1,175,000,000 Class A common shares of CCIV valued at USD 10 per share. Factoring in the stakes of the PIPE investors and the original Churchill Capital SPAC investors, the deal values Lucid Motors at $24bn.

When the deal closes, likely in 2Q 2021, the stock will trade under the symbol LCID.

Concerns regarding Lucid’s giant valuation are numerous: first of all, it is a pre-revenue company that will not deliver its first car to customers until the second half of this year. What is more, according to its projections, Lucid will not turn EBITDA-positive and FCF-positive until 2024 and 2025, respectively, reaching $1.5bn of FCF by 2026. Nevertheless, even based on those figures, Lucid is now trading at around 16x 2026E free cash flow. Lucid plans to deliver almost 22,000 cars in 2022 and the management figures to reach 251,000 EVs by 2026. In comparison, NIO, an established China-based premium EV manufacturer, as of the end of January 2021, had delivered a total of 82,866 units since the company’s inception, with more than 7,000 cars only in January 2021. To put all this in perspective, even though the China-based company needed a $1bn bailout from the Chinese government in 2020 to rise again, NIO’s enterprise value is about $86bn, implying that Lucid is already valued at 28% of NIO, even though it has yet to sell a vehicle or record a dollar of revenue.

Conclusions

All in all, what is clear given the model lineup and prices is that Lucid is going for the luxury sector of the vehicle market. For now, none of the mainstream auto manufactures captures the high-end EV segment. Tesla, which has been the standard-bearer for the entire EV sector, is in all respects a luxury brand but Lucid will initially pursue an even higher price point, before branching out into lower price and SUV segments.

Lucid has the know-how, with a former Tesla chief engineer as CEO but the EV sector is about to become just the normal auto sector as all manufacturers move to electric vehicles. So stand-alone EV companies are about to face a whole range of competitors. Indeed, such companies as Volvo, Ford and Jaguar Landrover plan to be entirely electric within 2025-2030 (4-9 years).

Lucid doesn't expect to be cash-flow positive until 2025 with new models coming on stream in 2022 and 2023 and plans to launch a rival to Teslas Model 3 in 2024-2025. With enhanced competition from legacy automakers, this makes achieving those goals even more important, to establish market share and differentiation with customers and not be just another car brand. Therefore, it will be essential for Lucid to deliver on its timeline and to scale up production and brand awareness and exclusivity.

CCIV is still trading at around 100 times the estimated 2025 FCF, based on an estimated $321 million in 2025 FCF. So, the fact that its shares are still up more than double what they were last July in its IPO means that CCIV is doing well against many of its July 2020 peer SPACs, which have achieved scarse results.

To conclude, also thanks to the transaction with CCIV, Lucid is now well funded, has a management team and CEO who knows the EV industry well. However, following the recent events surrounding CCIV stocks, it is not clear what will happen next and only time will have the last word.

Alessandro Maraldi