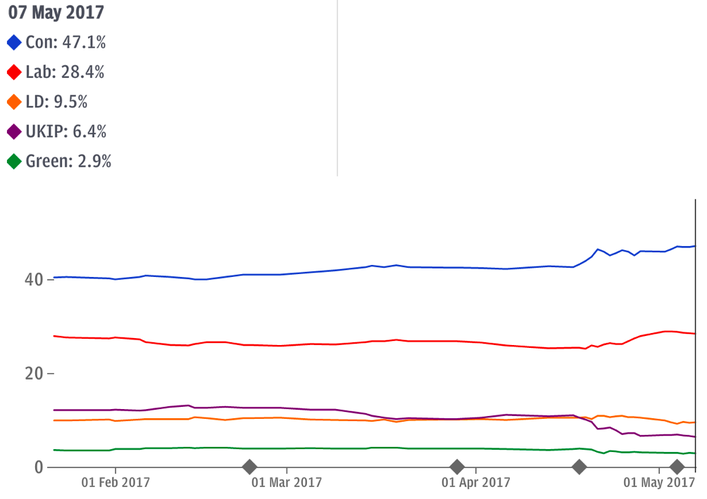

“There will be no early general election” proclaimed Theresa May’s official spokesman less than a month ago. A broken promise hardly seems to constitute a good beginning for an electoral campaign, yet the Conservative party is looking forward to a landslide: opinion polls are showing a 20% advantage over Labour. Such numbers were last witnessed back in 1983 when Margaret Thatcher won a 144-seat majority and the whole world was shifting towards a neo-liberal order.

Mrs. May justified the election as a necessary step to protect the Brexit process from the opposition in Parliament that plans to derail it. She declared that “the country is coming together but Westminster is not”. That is not quite correct: more than 40% of Britons think that Brexit was a mistake; on the other hand, the House of Commons has constituted no opposition to the government’s plans for Brexit, and has instead more than dutifully complied with the results of the referendum. Even Labour, the main opposition, has sided with the government.

The actual reason behind this move is that Theresa May is taking the chance of historically low Labour consensus to increase her working majority of 17 MPs to potentially more than 100. Furthermore, this election provides her leadership and government with the popular mandate they lacked. But implications on Brexit are also meaningful. The most evident result will be to enhance the PM’s authority over the Brexit process, provided that the Conservatives win. It is surprisingly hard to speculate what the PM, dubbed Theresa Maybe, will do of that freedom;

At the same time, the Lib Dems, who are the most pro-EU force, are expected to increase their presence in Parliament. To avoid losing seats in Remain voting areas (such as London, the university towns and the south-west of England), the Conservatives will be encouraged to choose candidates who support a softer Brexit;

Moreover, the election will free MPs from the current impasse: up to now, Remain-side MPs from Remain-voting constituencies were bound to support Brexit by the results of the referendum, and any talk of soft Brexit or Breversal was dismissed as anti-democratic treachery. The next MPs will campaign either for hard Brexit, soft Brexit or complete Breversal, and, if elected, legitimately stand up for whatever position they advocated, regardless of the referendum. This will provide those that support a soft Brexit with a louder voice in the debate;

On the other side, the Conservative leadership might take the chance to purge out Tory MPs who still support Remain, as suggested by the Daily Mail, as well as by Conservative activists. However, May might on the contrary use the election to set her government free from the 30-40 ultra-Eurosceptic MPs. The Tory backbenchers currently hold a strong influence over the party - which relies on a 17-seat majority in Commons - preventing any compromise with the EU. They would oppose the passing through of any deal which allowed for free movement of people. And they also refuse to pay the bill before leaving. Their hard line doesn’t allow May any concrete room to negotiate with the EU. The only solution would be not to include them in the list of Conservative candidates. Therefore, it appears that May’s gamble makes a softer Brexit more likely.

The trend of the Pound, which on news of an early election has surged to a sixth-month high, seems to point in this direction. Investors are expecting that the snap general election will end up supporting the cause for soft Brexit.

Major investment banks seem less confident. They fear that the government will fail to secure passporting rights for financial services, preventing them from serving European clients. Last week, JP Morgan announced that between 500 and 1,000 jobs may be relocated to Dublin, Frankfurt and Luxembourg in the short term. The bank will consider longer-term numbers once the negotiations finish. Deutsche Bank followed suit, saying it could move up to 4,000 jobs to continental Europe, namely Germany. Barclays instead will be adding staff to its offices in various European financial centres, such as Paris, Milan and, again, Frankfurt. While financial institutions have previously been indecisive and reluctant about relocating staff, they are now starting to move jobs in advance of Brexit, while also preparing large-scale plans for worst-case scenario.

Pietro Menoni