Is it possible for the price of one of the most traded commodities to turn negative?

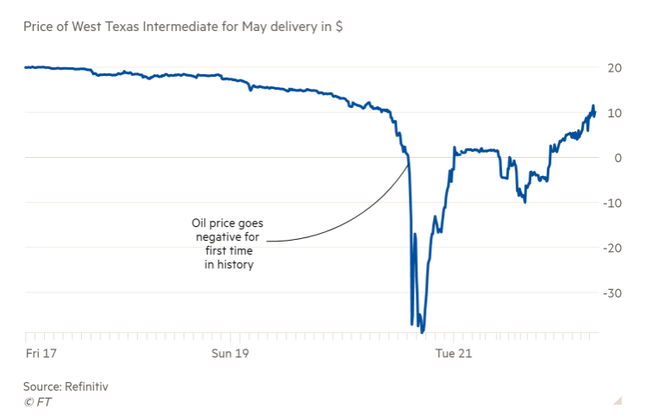

The reply of the market, during the COVID-19 epidemic, has been definitely yes. On April 20th, for the first time in history, the U.S. benchmark price for crude oil dipped into negative territory: the futures contracts for May delivery of WSI reached the value of minus $40.31 a barrel.

Does this mean that investors were literally paid to buy and store oil?

The lockdown in response to Coronavirus has basically frozen the global economy. Closed manufacturing plants, blocked airplanes and ships, less used cars and means of transport: since the end of February, the consumption of energy has drastically fallen. In the meantime, the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia increased oil extraction, before reaching an agreement in order to slightly bring it down. So, while the reduction of demand has been about 30%, companies have cut their production just by 10% (9,7 million barrels), hoping to maintain their market share.

This situation has caused a large offer surplus, without any buyer to absorb it. Storage capacity has in fact quickly filled up and the delivery of crude oil has become a huge problem, especially in the US. The main hub in Cushing, Oklahoma for example, maximum storage capacity of 76 million barrels, has already been filled with 55 million ballers and is expected to be full by Mid-May.

The clearest sign of this issue came as the WTI futures contracts, which need to be settled with physical delivery of crude oil, headed towards their expiry date: April 21st.

Normally the contracts, which are traded each month on CME Group’s New York Mercantile Exchange, are sold to demand sources that can physically take oil barrels, like refiners or airlines, without a great impact on the price. But this didn’t happen for the May contract. Since it appeared to be no buyers, traders and producers started to literally pay in order to get rid of crude oil. Selling at a negative price was better than dealing with the increasingly expensive physical storage. That’s basically how the WTI crude contract fell to minus $40.32 on Monday 20th April, expiring the day after at $10.01 a barrel.

After the WTI disaster, also the Brent Crude Oil futures contract followed the wave, touching $15.98 a barrel, the lowest since June 1999. Right now, it is traded a $21.80 a barrel, with a 62,72% loss compared to the beginning of February 2020 (around $60 a barrel).

The reply of the market, during the COVID-19 epidemic, has been definitely yes. On April 20th, for the first time in history, the U.S. benchmark price for crude oil dipped into negative territory: the futures contracts for May delivery of WSI reached the value of minus $40.31 a barrel.

Does this mean that investors were literally paid to buy and store oil?

The lockdown in response to Coronavirus has basically frozen the global economy. Closed manufacturing plants, blocked airplanes and ships, less used cars and means of transport: since the end of February, the consumption of energy has drastically fallen. In the meantime, the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia increased oil extraction, before reaching an agreement in order to slightly bring it down. So, while the reduction of demand has been about 30%, companies have cut their production just by 10% (9,7 million barrels), hoping to maintain their market share.

This situation has caused a large offer surplus, without any buyer to absorb it. Storage capacity has in fact quickly filled up and the delivery of crude oil has become a huge problem, especially in the US. The main hub in Cushing, Oklahoma for example, maximum storage capacity of 76 million barrels, has already been filled with 55 million ballers and is expected to be full by Mid-May.

The clearest sign of this issue came as the WTI futures contracts, which need to be settled with physical delivery of crude oil, headed towards their expiry date: April 21st.

Normally the contracts, which are traded each month on CME Group’s New York Mercantile Exchange, are sold to demand sources that can physically take oil barrels, like refiners or airlines, without a great impact on the price. But this didn’t happen for the May contract. Since it appeared to be no buyers, traders and producers started to literally pay in order to get rid of crude oil. Selling at a negative price was better than dealing with the increasingly expensive physical storage. That’s basically how the WTI crude contract fell to minus $40.32 on Monday 20th April, expiring the day after at $10.01 a barrel.

After the WTI disaster, also the Brent Crude Oil futures contract followed the wave, touching $15.98 a barrel, the lowest since June 1999. Right now, it is traded a $21.80 a barrel, with a 62,72% loss compared to the beginning of February 2020 (around $60 a barrel).

What happened to crude oil in excess?

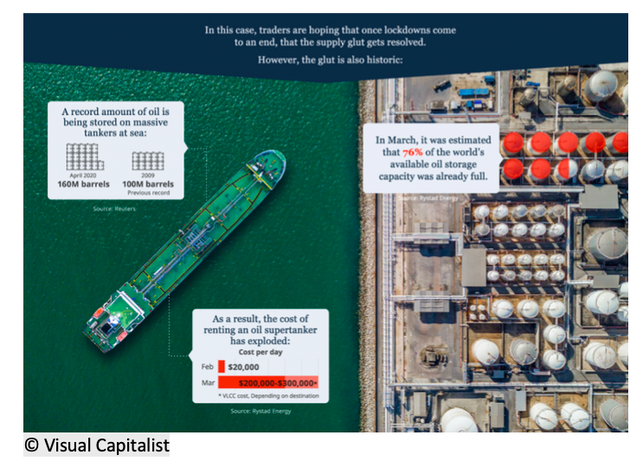

As already in March the 76% of the estimated world’s available storage capacity on land was full, the use of crude-oil sea storage has quickly increased, hitting a record of 160 million barrels on board. In order to manage oil glut, traders hurried to find places for their products, resulting in doubling the amount of oil on ships from two weeks ago.

“This is an unprecedented time in the history of tankers and while VLCC tanker storage is garnering the headlines, smaller crude and product tankers are also being used for storage” Gregory Lewis, shipping analyst with BTIG, reported to Reuters.

As a consequence, the price for oil tankers has increased like never before: average rates for VLCCs have reached highs of $350,000 a day, compared to $20,000 in April 2019.

“We’ve reached a point where there must be some kind of halt in production to suck up the glut,” said a tanker broker in Singapore. “It’s the first time ever that we get more calls to book ships to store oil than to move it.”

What will be the consequence of the oil crash in the US?

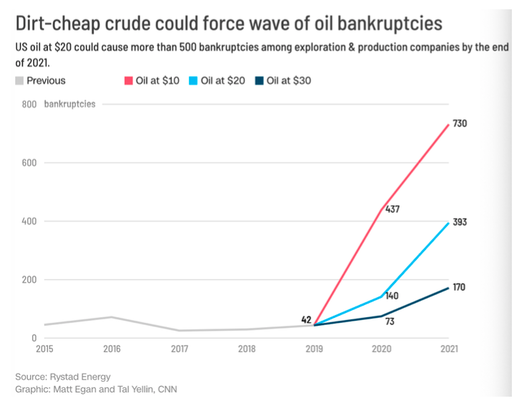

In the US oil revenues account for around 8% of GDP, a significant but not fundamental share, unlike other oil-exporter countries. Even so, the impact of oil price collapse over US companies can be disastrous. Since many of them had already a great amount of debt as a result of a decade of low borrowing costs, it will be hard for the majority to survive after the current crisis. The signs are clear: S&P Global Ratings in Mid-March reported a percentage of 94% oil and gas companies with distressed credit ratios and the bond yields have increased dramatically.

Considering that even low-cost oilfields require at least 49$ a barrel in order to make profits, negative prices are a total nightmare. Furthermore, also the stability of the price of futures contracts for June, around $20 a barrel, would result in the bankruptcy of 400 US oil companies by the end of 2021. In addition, trying to reorganize according to Chapter 11 requires financial sponsorship, which may be hard to find given the situation. Debtholders who usually swap debt for equity would not probably want that equity. In fact, even before the April crash investors were already worried by the energy sector’s weak financial performance, by far the worst of the S&P 500 over the last decade. For this reason, the only option left would be a total liquidation. Only a rapid growth of demand and prices can avoid this terrible scenario of bankruptcies.

Some like Reid Morrison, US energy leader at PwC, forecast that industry’s biggest players Exxon and Chevron, could take this as a lucrative buying opportunity, exploiting the eventual fire-sale prices of prime acreage: "Those with strong balance sheets will be able to take advantage of the situation”. Anyway, he also pointed out that these companies will probably be still extremely cautious in the next six months, in order to defend their dividends.

What about other countries?

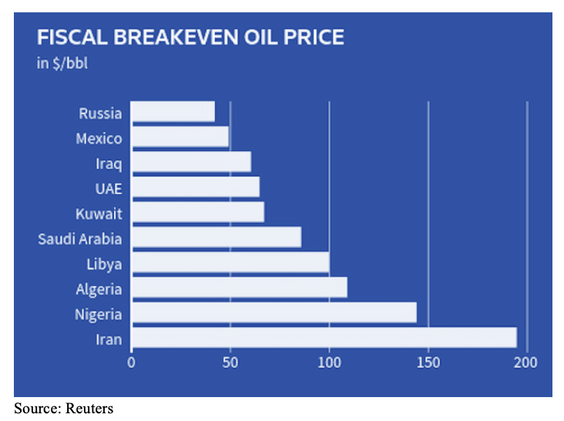

Oil-dependent counties are also seriously threatened by the oil crash. Their tolerance can be measured by the “breakeven point”, the price of oil needed to balance their budget.

The worst-hit will surely be, according to NKC African Economics, states like Nigeria, Angola, Gabon and the Congo Republic, which “will be scrambling to borrow from lenders who already have serious doubts about their ability to repay, and who will be tough negotiators when it comes to determining the value of the mineral assets these governments will try suggesting as collateral”.

Nigeria’s Long-Term Foreign-Currency IDR, for example, had already been downgraded by Fitch Rating on 6th April from ‘B+’ to ‘B’, as a reflection of the ongoing pressures on its external finances caused by oil prices and the COVID-19 shock. Its government in fact depends on oil for 60% of its revenue and 90% for its foreign exchange, with a breakeven point of $144 a barrel. If the global economy doesn’t recover, bankruptcy would not be a far possibility.

The same effects can be spotted over poorer countries of Latin American, like Venezuela or Ecuador, whose economies almost completely rely on crude oil sales. International Monetary Fund forecasts at least a shrink of 15% for Venezuela’s economy, while Ecuador’s President Lenin Moreno has called the oil market collapse the country’s “most critical moment in its history”.

By contrast. Saudi Arabia and Russia will be less affected. Even if their breakeven points are respectively $84 and $42 a barrel and oil accounts a great portion of their GDP, thanks to great wealth reserves, they would probably be able to cover the budget shortfall in the long term.

Oil-dependent counties are also seriously threatened by the oil crash. Their tolerance can be measured by the “breakeven point”, the price of oil needed to balance their budget.

The worst-hit will surely be, according to NKC African Economics, states like Nigeria, Angola, Gabon and the Congo Republic, which “will be scrambling to borrow from lenders who already have serious doubts about their ability to repay, and who will be tough negotiators when it comes to determining the value of the mineral assets these governments will try suggesting as collateral”.

Nigeria’s Long-Term Foreign-Currency IDR, for example, had already been downgraded by Fitch Rating on 6th April from ‘B+’ to ‘B’, as a reflection of the ongoing pressures on its external finances caused by oil prices and the COVID-19 shock. Its government in fact depends on oil for 60% of its revenue and 90% for its foreign exchange, with a breakeven point of $144 a barrel. If the global economy doesn’t recover, bankruptcy would not be a far possibility.

The same effects can be spotted over poorer countries of Latin American, like Venezuela or Ecuador, whose economies almost completely rely on crude oil sales. International Monetary Fund forecasts at least a shrink of 15% for Venezuela’s economy, while Ecuador’s President Lenin Moreno has called the oil market collapse the country’s “most critical moment in its history”.

By contrast. Saudi Arabia and Russia will be less affected. Even if their breakeven points are respectively $84 and $42 a barrel and oil accounts a great portion of their GDP, thanks to great wealth reserves, they would probably be able to cover the budget shortfall in the long term.

What can be the prediction for the next months?

“What the energy market is telling you is that demand isn’t coming back any time soon, and there’s a supply glut,” says Kevin Flanagan, head of fixed income strategy for Wisdomtree Asset Management, in New York. WTI contracts for delivery in June are currently trading around $16 a barrel, while Brent futures contracts are maintaining a price of $21.80 a barrel.

But, unless the demand rapidly grows, the storage limitations seen the previous month may remain a problem and cause a worse price collapse. The production cut in fact, as stated by Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Agency, could be “insufficient to rebalance the market immediately due to the scale drop in demand”.

Further reductions, on the other hand, would be highly expensive and difficult to handle, especially for oil-producing states who would lose their main source of income.

The future right now is highly uncertain, but the terrible effect of extended lockdown over the oil industry is almost assured.

Sara Chiuri

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

“What the energy market is telling you is that demand isn’t coming back any time soon, and there’s a supply glut,” says Kevin Flanagan, head of fixed income strategy for Wisdomtree Asset Management, in New York. WTI contracts for delivery in June are currently trading around $16 a barrel, while Brent futures contracts are maintaining a price of $21.80 a barrel.

But, unless the demand rapidly grows, the storage limitations seen the previous month may remain a problem and cause a worse price collapse. The production cut in fact, as stated by Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Agency, could be “insufficient to rebalance the market immediately due to the scale drop in demand”.

Further reductions, on the other hand, would be highly expensive and difficult to handle, especially for oil-producing states who would lose their main source of income.

The future right now is highly uncertain, but the terrible effect of extended lockdown over the oil industry is almost assured.

Sara Chiuri

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.