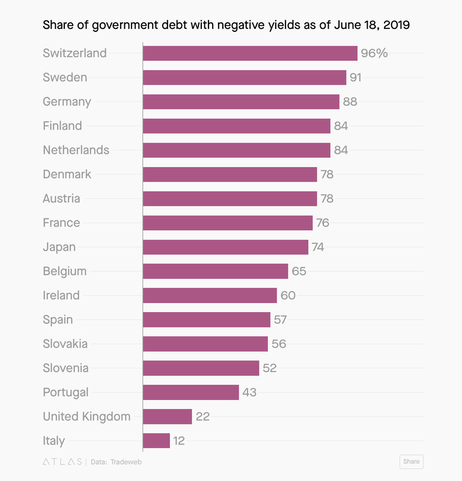

Today, around 30% of bonds worldwide are trading at negative rates – which implies that, for up to $17tn of outstanding debt, creditors are “paying” to lend money.

From a practical point of view, what investing money in negative-yielding bonds means, is that you get back less than what you invest.

Hence, a very natural question arises: why would anyone do it?

The initial idea

Let’s first explain how we got there and who decided that the interest should be negative.

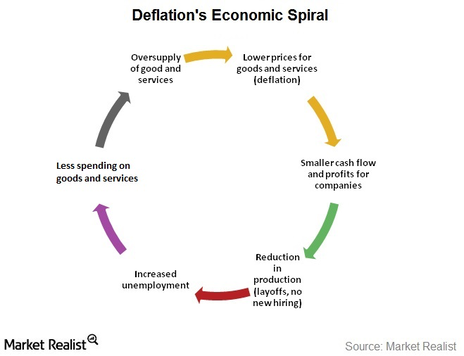

Since 2014, the European Central Bank (ECB) was concerned about deflation. When deflation occurs, consumers have more purchasing power because prices are falling but, instead of buying, they will save. The firms will have to liquidate those products that no one wants to buy anymore, the aggregate demand will go down, unemployment will skyrocket and eventually firms will be collecting bad debts and creating a deflationary spiral.

Hence, what ECB decided to do, was to decrease its deposit rate and, most recently on September 18th 2019, the deposit facility rate was lowered further into negative territory and now stands at -0.50%, meaning that banks storing reserves at the ECB will pay this negative interest for the storage.

The trick that allows banks to earn

As a bank, today, you have no incentive to keep your assets parked at ECB and losing a 0.50% of your own money. What you prefer doing is buying bonds with a -0.50% yield, resell them to the ECB with a -0.60% yield and gain the difference.

Why would anyone buy such a bond?

If you can’t think of a reason, here are some: deflation, liquidity, rules.

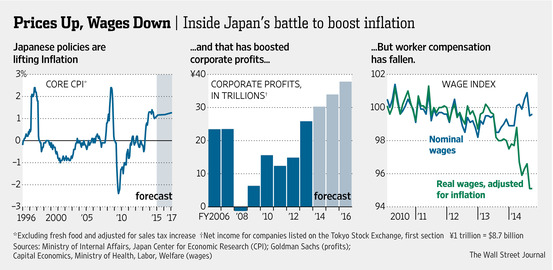

If consumers think that the price of goods will fall enough to compensate for the money they lost in investing, the loss might still be worth it.

Deflation is the reason why a negative-yielding bond can, ideally, turn profitable: consumers will use their savings to buy more later on. This particular reason is why these bonds are so popular in Japan where the country has high deflation since the 1990s.

Another reason for which big investors (insurers or financial institutions, as well as pension funds) agree to lose a small portion of money on the investment is that they trust the government to keep their money. The government debt is liquid and can be sold easily.

Moreover, some financial institutions are forced to follow regulatory requirements such as holding liquid assets: this is the case of banks.

Risks

Government bonds of those countries that are financially stable have always been considered as a safe investment given that the government, only in case of high domestic debt, will manipulate taxes or create more money. But even if the idea of negative-yielding bonds was supposed to stimulate economic activity, it is not an ideal situation and the consequences could be damaging. Think, for example, about a bank holding mortgage bonds that are tied to the same interest rate: the profit for the bank would be lower and it could soon decide to lower the lending amount.

Investors are not just paying for the bond, but are paying how much, above par, they are willing to bet that the growth rate will keep being low and deflation will stay. When there is going to be even a small change in the opposite direction of deflation, the losses will be impressive.

According to Jim Bianco, the founder of Bianco Research, “Bondholders would lose 50% of their money if yields on Swiss bonds go up just 2% points”.

A new entry

The most recent example is Greece. The country went from being on the edge of being kicked out from the European Union to the point where other countries are paying it to be able to lend it money. On 9th of October, the country issued short-term negative-yielding bonds for a total of 487,5 million euros. After 2008, Greece’s debt was considered a dangerous investment and was the whole economy had to be rescued by the International Monetary Fund. As the Greek economy will be doing better (a forecast suggests a 2.8% growth), the bondholders will be making money. However, this country’s economy is unpredictable and unsteady, so investors should think twice before investing.

Sofiya Sergeeva