The O.E.C.D. (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) has released an 18-page proposal on October 9th, aimed at giving G-20 countries the possibility to review the general corporate taxation system to be applied to large Multi-National Entities (MNEs).

“In a digital age, the allocation of taxing rights can no longer be exclusively circumscribed by reference to physical presence,” the proposal claims. “The current rules dating back to the 1920s are no longer sufficient to ensure a fair allocation of taxing rights in an increasingly globalized world.” The key point is that governments can charge MNEs with taxes only if these have a physical presence on their soil. Yet, this principle becomes controversial when it comes to tech companies, which can make huge profits in countries where they do not actually have a physical presence.

As a matter of fact, the current taxing rules have left room for several BEPS practices by large multinational enterprises in the last few decades. The term BEPS stands for ‘base erosion and profit sharing’, and it is a corporate tax planning strategy used by large MNEs to shift their profits from higher tax jurisdictions to lower tax ones, thus eroding the tax base of the higher tax jurisdictions and minimizing their tax bills. It comes as no surprise that the area in which companies have been most aggressively accomplishing this strategy is the digital economy, with digital groups such as Facebook, Apple and Google significantly involved in these practices.

After several months of negotiations behind-the-scenes, the OECD’s proposal is now open to a public consultation process. It brings together 134 countries for multilateral negotiation of international tax rules and it would reallocate profits and taxing rights to countries and jurisdictions where Multi-National Entities operate. It is thus aimed at closing gaps in international taxation for these companies that allegedly reduce tax burden in their home country through tax inversions and migrations of intangibles to lower tax jurisdictions.

“In a digital age, the allocation of taxing rights can no longer be exclusively circumscribed by reference to physical presence,” the proposal claims. “The current rules dating back to the 1920s are no longer sufficient to ensure a fair allocation of taxing rights in an increasingly globalized world.” The key point is that governments can charge MNEs with taxes only if these have a physical presence on their soil. Yet, this principle becomes controversial when it comes to tech companies, which can make huge profits in countries where they do not actually have a physical presence.

As a matter of fact, the current taxing rules have left room for several BEPS practices by large multinational enterprises in the last few decades. The term BEPS stands for ‘base erosion and profit sharing’, and it is a corporate tax planning strategy used by large MNEs to shift their profits from higher tax jurisdictions to lower tax ones, thus eroding the tax base of the higher tax jurisdictions and minimizing their tax bills. It comes as no surprise that the area in which companies have been most aggressively accomplishing this strategy is the digital economy, with digital groups such as Facebook, Apple and Google significantly involved in these practices.

After several months of negotiations behind-the-scenes, the OECD’s proposal is now open to a public consultation process. It brings together 134 countries for multilateral negotiation of international tax rules and it would reallocate profits and taxing rights to countries and jurisdictions where Multi-National Entities operate. It is thus aimed at closing gaps in international taxation for these companies that allegedly reduce tax burden in their home country through tax inversions and migrations of intangibles to lower tax jurisdictions.

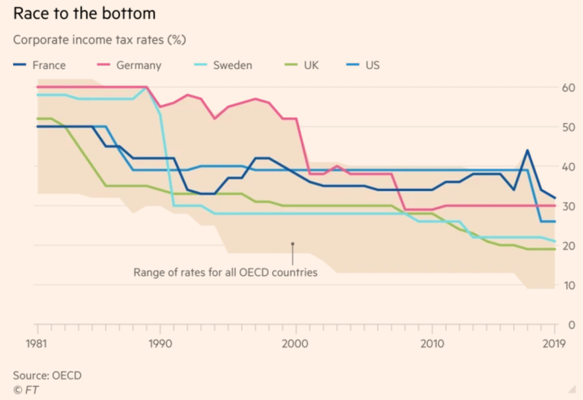

Clearly, the proposal goes to the advantage of big countries such as U.S., Germany, UK, China and developing economies, which will eventually be able to take a share of the companies’ enormous revenues. The ones facing losses instead will be the low tax jurisdictions, and so-called fiscal heavens such as Switzerland and Luxemburg, which have been keeping low their tax rates to attract investments from global companies. The approval of the proposal would surely cut their tax revenue, as it would not be so beneficial for multinational companies to register in those places.

Whether multinationals would lose or gain from such proposal is a matter for debate. The OECD has stated that the companies that would be targeted by the changes would be those with an annual revenue higher than 750 million euros. Surprisingly, Amazon welcomed the proposal, defining it ‘an important step forward’. According to the e-commerce colossus, international agreements are crucial in order to avoid the risk of double taxation and unilateral acts by single countries, which would be detrimental to the growth of world trade.

The OECD’s proposal consists of two main parts. The first one, called Pillar One, provides new rules on tax jurisdiction (often called nexus rules). More specifically, they are aimed at finding an agreed approach to a fair distribution of profits of Multi-National Entities among countries in which their business is carried on, including those ones in which the enterprise does not have a physical presence. The second one, called Pillar Two, instead is about a set of new rules that would establish a global minimum tax regime for MNEs.

Under Pillar One, three proposals have been articulated to develop a consensus-based solution on how taxing rights on income generated from cross-border activities in the digital age should be allocated among countries. Namely, the “user participation” proposal argues that the existing tax framework ignores the value that certain business models derive from user participation.

Broader in scope are the “marketing intangibles” proposal and the “significant economic presence” proposal, which refer not only to digital companies but potentially to any multinational business that depends on intangible investment such as branding or patents, such as German carmakers and French luxury brands.

The tax plan above described is a genuine example of how international cooperation might be crucial to tackle the challenges of globalization rather than a retreat into nationalism.

Annamaria Palmieri