The surge in private debt arms of Private Equity Firms does not come without conflicts of interests.

Private debt is the flavour of the day in the US, and, increasingly, also in Europe. The definition of private debt is not always clear but it mostly refers to bespoke non-bank loans that are privately originated. In most cases, these are loans extended by dedicated funds to small-medium companies to keep afloat, run their ordinary operations or to fund operations of extraordinary nature (M&A, LBOs). These are credit needs for which traditionally companies would turn to banks, but it is precisely when banks retrench, because of the regulatory pressure on capital requirements, that private debt funds step in.

According to many observers familiar with this market, the current conditions of the private debt segment have never been more frenzied. In particular, the European market seems to offer an increasing and yet not fully exploited potential. “This asset class is still pretty immature in Europe” – said Micheal Dennis, the co-head of Ares’s European direct-lending platforms – “Bank retrenchment in Europe is still a theme that is being played out… This favour firms like us which have lots of capital to deploy”.

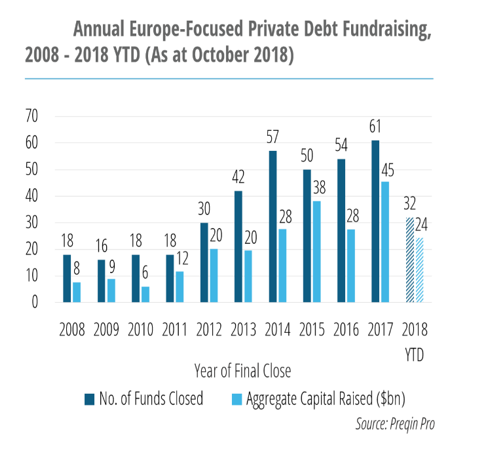

To give an idea of the market size, BofA reports that the US market has swelled from about $300bn in private debt AUM in 2010 to about $700bn at the end of last year. As for the amount of funds raised in a year, last complete data available are referred to 2017: in that year fundraising topped to $100bn of which about $45bn concern European-focused funds.

The scale of inflows confirms that private debt is, in Europe like in the US, a phenomenon which deserves a lot of attention. Indeed, there has been a lot of discussion concerning the causes and the risks of this surge in credit provided by the non-bank sector.

Besides this, another type of analysis that can be carried out deals with the sponsors of these funds. Based on the list of the largest private-debt funds active in Europe, we can see that the sponsors of the funds are first and foremost Private Equity and Asset Management firms (having private equity and credit funds).

This represents indeed a global trend involving all the main Private Equity firms, including Blackstone, KKR, Ares Management, Apollo Management and Bain Capital, that have established credit arms, which sponsor, among other specialties, also private debt funds. Moreover, these have become in many cases their most active businesses, largely surpassing by AUM their private equity arms.

Private debt is the flavour of the day in the US, and, increasingly, also in Europe. The definition of private debt is not always clear but it mostly refers to bespoke non-bank loans that are privately originated. In most cases, these are loans extended by dedicated funds to small-medium companies to keep afloat, run their ordinary operations or to fund operations of extraordinary nature (M&A, LBOs). These are credit needs for which traditionally companies would turn to banks, but it is precisely when banks retrench, because of the regulatory pressure on capital requirements, that private debt funds step in.

According to many observers familiar with this market, the current conditions of the private debt segment have never been more frenzied. In particular, the European market seems to offer an increasing and yet not fully exploited potential. “This asset class is still pretty immature in Europe” – said Micheal Dennis, the co-head of Ares’s European direct-lending platforms – “Bank retrenchment in Europe is still a theme that is being played out… This favour firms like us which have lots of capital to deploy”.

To give an idea of the market size, BofA reports that the US market has swelled from about $300bn in private debt AUM in 2010 to about $700bn at the end of last year. As for the amount of funds raised in a year, last complete data available are referred to 2017: in that year fundraising topped to $100bn of which about $45bn concern European-focused funds.

The scale of inflows confirms that private debt is, in Europe like in the US, a phenomenon which deserves a lot of attention. Indeed, there has been a lot of discussion concerning the causes and the risks of this surge in credit provided by the non-bank sector.

Besides this, another type of analysis that can be carried out deals with the sponsors of these funds. Based on the list of the largest private-debt funds active in Europe, we can see that the sponsors of the funds are first and foremost Private Equity and Asset Management firms (having private equity and credit funds).

This represents indeed a global trend involving all the main Private Equity firms, including Blackstone, KKR, Ares Management, Apollo Management and Bain Capital, that have established credit arms, which sponsor, among other specialties, also private debt funds. Moreover, these have become in many cases their most active businesses, largely surpassing by AUM their private equity arms.

General justifications for this phenomenon stem from the synergies that these two illiquid investments present in terms of expertise and analysis required, network with enterprises and similar investment process.

But this is only a part of the story: there are other benefits for a sponsor playing both on the equity and on the credit side of the capital structure but, at the same time, “there are legal and ethical problems to buying debt in your own companies”, warns John Moulton, founder of Alchemy Partners.

To understand that, it’s useful to consider a second table, retrieved from the same data provider Prequin, showing the most prominent private-debt backed deals in Europe (as at October of 2018) where we can see that they are primarily, not very surprisingly, private equity takeovers.

These data don’t give us details on the private debt funds backing these deals, therefore we don’t know exactly, for example, if and how much of the debt supporting Blackstone’s Acquisition of Aon Corporation’s Employee Benefits Unit is on the balance sheet of GSO, that is, its own credit arm. However, as my professor at NYU-Stern James Finch – former Head of US Capital Markets at Credit Suisse - used to tell us “You can bet your ass, that a PE firm is going to be in line to get a big chunk of the debt backing its own deal”.

But this is only a part of the story: there are other benefits for a sponsor playing both on the equity and on the credit side of the capital structure but, at the same time, “there are legal and ethical problems to buying debt in your own companies”, warns John Moulton, founder of Alchemy Partners.

To understand that, it’s useful to consider a second table, retrieved from the same data provider Prequin, showing the most prominent private-debt backed deals in Europe (as at October of 2018) where we can see that they are primarily, not very surprisingly, private equity takeovers.

These data don’t give us details on the private debt funds backing these deals, therefore we don’t know exactly, for example, if and how much of the debt supporting Blackstone’s Acquisition of Aon Corporation’s Employee Benefits Unit is on the balance sheet of GSO, that is, its own credit arm. However, as my professor at NYU-Stern James Finch – former Head of US Capital Markets at Credit Suisse - used to tell us “You can bet your ass, that a PE firm is going to be in line to get a big chunk of the debt backing its own deal”.

The Volcker Rule, the controversial regulation enacted in the aftermath of the crisis in the US, forced the banks that were active in private equity to shed most of these assets, recognizing an intrinsic conflict of interests arising from a unique financial institution being a shareholder and a debtholder of the same company. This conflict is even more striking for this wild-west of unregulated PE companies and the question is unavoidable: how can be the interest of LPs invested in its PE fund be aligned with that of LPs committed to the PD fund? In particular, there are two areas at least in which these conflicts cannot be ignored by regulators.

First of all, there’s a conflict in the pricing and in the terms of all this debt, whenever private debt arms constitute a substantial investor in the debt originated in a private equity transaction. Indeed, given the size of these funds mentioned above, it can be safely deduced that these groups can exercise a strong pressure on all the other loan providers (banks, independent funds) to align their pricing to more favourable conditions for borrowers to stay competitive.

A second type of conflict derives from the possibility of self-dealing. Both shareholders and lenders might wish the portfolio company to remain alive as a zombie company in order to keep charging fees to the LPs, even when, for example, an orderly bankruptcy procedure would be in the best interests of both groups of investors.

Stretching this argument to the limit, it’s not even needed that both the private equity and private debt funds belong to the same sponsor. Another easy type of collusion that could occur is if one asset management firm is a debt holder in the portfolio company controlled by a second AM firm, while the latter is a lender to a company owned by the former. Both could find it beneficial to collude with the aim of maximising their interests (and to the detriment of LPs, co-investors and fellow debt holders).

These issues are clear as day, and the size of the private debt market tells us how extensively spread they can be. Enforcing hyper-regulation in one side of the market (clear example of the Volcker Rule), while leaving huge regulatory voids that can be filled by an entire universe of “shadow-banking” players, is irresponsible and useless. Regulators should wake up soon and face the reality that they have in front of their eyes.

Giacomo Longoni

First of all, there’s a conflict in the pricing and in the terms of all this debt, whenever private debt arms constitute a substantial investor in the debt originated in a private equity transaction. Indeed, given the size of these funds mentioned above, it can be safely deduced that these groups can exercise a strong pressure on all the other loan providers (banks, independent funds) to align their pricing to more favourable conditions for borrowers to stay competitive.

A second type of conflict derives from the possibility of self-dealing. Both shareholders and lenders might wish the portfolio company to remain alive as a zombie company in order to keep charging fees to the LPs, even when, for example, an orderly bankruptcy procedure would be in the best interests of both groups of investors.

Stretching this argument to the limit, it’s not even needed that both the private equity and private debt funds belong to the same sponsor. Another easy type of collusion that could occur is if one asset management firm is a debt holder in the portfolio company controlled by a second AM firm, while the latter is a lender to a company owned by the former. Both could find it beneficial to collude with the aim of maximising their interests (and to the detriment of LPs, co-investors and fellow debt holders).

These issues are clear as day, and the size of the private debt market tells us how extensively spread they can be. Enforcing hyper-regulation in one side of the market (clear example of the Volcker Rule), while leaving huge regulatory voids that can be filled by an entire universe of “shadow-banking” players, is irresponsible and useless. Regulators should wake up soon and face the reality that they have in front of their eyes.

Giacomo Longoni