Mining and metals giant Rio Tinto has reached an agreement with private equity EMR Capital and Indonesian coal company Adaro Energy to sell its 80 percent stake in Kestrel Coal Mine for $2.25 billion. Kestrel is an underground coal mine located 51 km northeast of Emerald in Central Queensland, Australia, that produces high-quality coking and thermal coal, key irreplaceable ingredients in the production of steel and in the electricity generation, respectively.

The transaction marks a further development in Rio Tinto’s objective to offload all its coal assets. A week before the sale of Kestrel, Glencore acquired Rio Tinto’s Hail Creek Mine for $1.7 billion, whereas Whitehaven Coal bought Rio Tinto’s Queensland project for $200 million. A year earlier, Rio sold its Hunter Valley operations to Glencore, while its Coal & Allied Industries unit went to Chinese Yancoal, raising $3.8 billion in total. The Kestrel sale would conclude Rio Tinto’s complete disposal of its coal assets, making it the first mining titan to exit the coal industry.

However, Rio Tinto’s retreat is far from being a harbinger of exodus from the coal industry at large. Firstly, the sequence of disinvestments is mainly motivated by the shift of Rio’s vector of development that gained momentum with Jean-Sébastien Jacques’s appointment as CEO in 2016. The sale of auxiliary assets allows Rio Tinto to redeploy the available resources, which also includes $9 billion harvested through coal assets sale, on Rio’s core commodity businesses - aluminum, bauxite, copper and iron ore. Although UBS analysts expect that the proceeds from the sales would be employed to reward shareholders through buybacks, RBC suggests that a strong balance sheet enables Rio Tinto to fund acquisitions aimed at boosting its core business. In addition, Rio’s departure from coal, which is considered as the “dirtiest” among fossil fuels, may allow Rio Tinto to attract a wider net of “environmentally conscious” investors. An increasing number of investors enlisted in the environmental, social and governance (ESG) conscious investors cohort would restrict their exposure to carbon-intensive businesses, often by including special coal exclusion clauses in their agenda.

Secondly, Rio’s backtrack from coal is in stark contrast with the behavior of other mining giants such as Anglo American, BHP Billiton, Glencore, and Vale. Glencore’s determined expansion of its coal operations in Australia through the acquisitions of Rio Tinto’s assets is already discussed above. Glencore’s CEO Ivan Glasenberg stated that coal has been “under-invested for over the years”. In unison with his optimistic colleague, Andrew Mackenzie, the CEO of BHP Billiton, argues that the lower-carbon economy would not mitigate the demand for high-quality coal. Similarly, Anglo-American, whose share prices rose almost fivefold since 2016 due to commodity price rebound, is cautiously confident about its large coal operations in South Africa and Australia. With the election of Cyril Ramaphosa, who previously established a miners union, as the president, Anglo-American is hopeful to obtain a foothold better than during Zuma’s regime.

The transaction marks a further development in Rio Tinto’s objective to offload all its coal assets. A week before the sale of Kestrel, Glencore acquired Rio Tinto’s Hail Creek Mine for $1.7 billion, whereas Whitehaven Coal bought Rio Tinto’s Queensland project for $200 million. A year earlier, Rio sold its Hunter Valley operations to Glencore, while its Coal & Allied Industries unit went to Chinese Yancoal, raising $3.8 billion in total. The Kestrel sale would conclude Rio Tinto’s complete disposal of its coal assets, making it the first mining titan to exit the coal industry.

However, Rio Tinto’s retreat is far from being a harbinger of exodus from the coal industry at large. Firstly, the sequence of disinvestments is mainly motivated by the shift of Rio’s vector of development that gained momentum with Jean-Sébastien Jacques’s appointment as CEO in 2016. The sale of auxiliary assets allows Rio Tinto to redeploy the available resources, which also includes $9 billion harvested through coal assets sale, on Rio’s core commodity businesses - aluminum, bauxite, copper and iron ore. Although UBS analysts expect that the proceeds from the sales would be employed to reward shareholders through buybacks, RBC suggests that a strong balance sheet enables Rio Tinto to fund acquisitions aimed at boosting its core business. In addition, Rio’s departure from coal, which is considered as the “dirtiest” among fossil fuels, may allow Rio Tinto to attract a wider net of “environmentally conscious” investors. An increasing number of investors enlisted in the environmental, social and governance (ESG) conscious investors cohort would restrict their exposure to carbon-intensive businesses, often by including special coal exclusion clauses in their agenda.

Secondly, Rio’s backtrack from coal is in stark contrast with the behavior of other mining giants such as Anglo American, BHP Billiton, Glencore, and Vale. Glencore’s determined expansion of its coal operations in Australia through the acquisitions of Rio Tinto’s assets is already discussed above. Glencore’s CEO Ivan Glasenberg stated that coal has been “under-invested for over the years”. In unison with his optimistic colleague, Andrew Mackenzie, the CEO of BHP Billiton, argues that the lower-carbon economy would not mitigate the demand for high-quality coal. Similarly, Anglo-American, whose share prices rose almost fivefold since 2016 due to commodity price rebound, is cautiously confident about its large coal operations in South Africa and Australia. With the election of Cyril Ramaphosa, who previously established a miners union, as the president, Anglo-American is hopeful to obtain a foothold better than during Zuma’s regime.

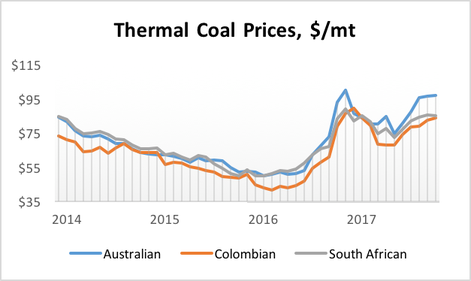

Despite general pressure engendered by environmental concerns, current fundamental factors seem to be favourable for the coal industry. Parallel to the general bounce back of commodity prices, prices for thermal and metallurgical coal experienced a dramatic rally since 2016. The rally has granted mining multinationals a prolonged period of great margins; for instance, Glencore’s production cost of coal averages about $48 per ton. The price upsurge is primarily dictated by the interplay between the climbing demand instigated by the economic reinvigoration of developing countries and stagnated supply of coal that was unable to predict the price hike and suffered from the lack of new investments. Indeed, Glencore’s Ivan Glasenberg anticipates the resurgence of the emerging economies “to burn more coal… it is the cheapest form of energy production in the world. Poorer and impoverished nations have no alternative.”

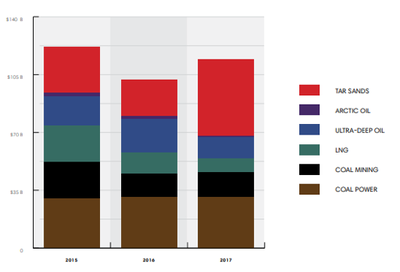

Furthermore, the aforementioned trend of divestments from coal-associated assets due to the environmental concerns seems to be mostly eschewed by major banks. The world’s largest banks are preoccupied with substituting the missing finance of funds. The total volume of major bank’s commitments to “heavy” fossil fuels projects such as tar sands, Arctic and deep-water oil extraction, LNG export, coal mining increased by 11 percent last year. After suffering a substantial post-Paris Climate Accord decline, financing of coal mines has climbed back to its pre-2016 level. Furthermore, once numbers for Chinese institutions are disregarded, the investment volume has more than doubled during 2017. Of the $52 billion pumped into coal mining between 2015 and 2017, Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse, Citi and Deutsche Bank account for largest commitments among Western banks.

Sultan Massalov

Sultan Massalov