The recent OPEC+ production cut has sparked significant interest in the oil market. The decision to cut oil production could have far-reaching implications for the global economy. What will be the impact of this decision on the oil market and the wider macroeconomic effects?

OPEC supply cut

Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” has given us one of the most indelible and haunting stories of the 20th century, imagining a world where control lies in the hands of a select few and where history is rewritten to fit the narrative of those in power. Similar to the power that The World Controllers hold in the book, OPEC+ has long controlled the oil supply of the world and, thus, the effects of its policies have visible consequences on all of the world’s economies.

OPEC+ is an alliance between the members of OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) and some of the large external oil-producers of the world. Together, OPEC+, that includes countries such as Saudi Arabia, Russia and Venezuela, controls more than half of the world’s petroleum exports and over 80% of its reserves. Needless to say, they hold immense economic and political power by strictly regulating the amount of oil produced, effectively operating as an economic cartel and have been known to leverage their power by adjusting the supply in their favor.

While in EMEA oil is not exactly scarce, it is important to note that the majority of it is concentrated in the Middle East and in Northern Africa, effectively leaving Europe (and especially the EU) with little to no oil of their own. Traditionally, the Europe has imported the oil it needed from Russia, the US, Norway (one of the very few European countries with significant oil reserves) and OPEC countries, but since the Russian-Ukrainian conflict has risen, most countries of the Old Continent have experienced supply chain issues, as they strived to cut Russian imports. This led to the “Energy crisis” that started in 2021, where Europe has had to find alternatives to the cheap Russian resources. This opportunity was exploited at its best by OPEC+, especially by Saudi Arabia, Libya and Kazakhstan, which became important trade partners of the EU at the expense of the Moscow government. However, this meant that the cartel now holds important leverage over the EU, and they made sure to make the most of it: despite the Western World’s diplomatic efforts (that sometimes actually resulted in promises by the cartel), OPEC+ has adjusted their output of oil however it pleased to, even as recently as April. But is this last alteration just another instance of the boy who cried wolf, a measure that lacks solid reasoning, or will OPEC+ defy the West and stick to their plans?

Economic outcome

The energy crisis has had a major impact on the supply chains and the macroeconomic stability of the world. High volatility in energy prices is a key component of many broad inflation indicators.

In EMEA, average inflation in 2021 was 2.9%, and reached a historical high of 9.2% in 2022, on account of the war in Ukraine and the exacerbation of energy issues.

Inflation in Europe has a different amplifying mechanism than in the United States, being driven largely by energy prices in the former, and largely by demand shocks in the latter.

The pandemic generated considerable supply chain stress exogenously, as many ports and other transit hubs were forced to reduce their capacity due to human contact restrictions. As these restrictions were eased, and on account of increased currency floating in the economy, especially in the United States, consumer demand rose sharply, especially for services, which put upward pressure on prices. Added to that was the rising cost of fuel for industry and for consumers as well, which made shipment more expensive and, subsequently, drove up the prices of the final goods and services available for sale.

The relationship between oil and the macroeconomy has been studied extensively. Historical evidence, especially from the two oil shocks which sent the United States into a period of high persistent inflation, would reasonably lead to the conclusion that the aforementioned relationship is strong. Generally, the current theoretical framework indicates that increases in oil prices reduce output. Moreover (Sill, 2007), the overall reduction of wealth in the economy results in decreased demand as well.

Consumption changes are not perfectly understood. For many years, economists believed that there was a clear difference between savings and consumption patterns between net importers and net exporters, which made price declines a net benefit for the world economy because gains by importers more than offset losses by exporters. It can reasonably be inferred that equity markets should perform in inverse correlation with price movements, as lower prices would lead to increased expected output, thus driving up stock valuations. However, as noted in research by the IMF (Obstfeld et.al., 2016), equity markets seem to be directly correlated with the direction of oil price movements. Therefore, the demand side of oil shocks remains subject to further research.

Recent academic findings on the Euro area (Holm-Hadulla, Hubrich, 2017) suggests the correlation between the macroeconomic indicators and oil shocks is stronger in “adverse regime”- that is, when oil prices increase. Inflation expectations were found to adjust similarly to oil price movements, but there was much higher upward sensitivity.

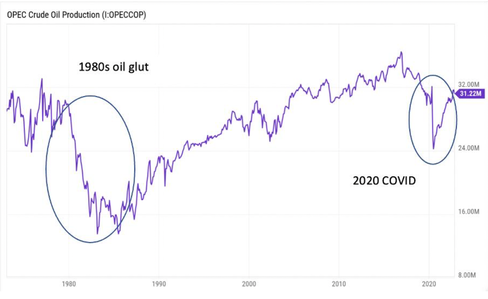

A look at the past

This is not the first time in history that OPEC has decided to cut the production of crude oil. In fact, the decision to manipulate the supply side of the market for oil is something that OPEC+ has done since its institution and this is not a particularly bad thing, per se. According to the OPEC website, their mission is “to coordinate and unify the petroleum policies of its Member Countries and ensure the stabilization of oil markets in order to secure an efficient, economic, and regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers, and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry.” This means that “manipulating” oil prices by interfering is part of their job with the aim of stabilizing prices without major fluctuations. They have intensively done so in the 80s during the so-called “1980s oil glut”. The energy crisis faced in the 70s caused a drop in demand that resulted in a major surplus of crude oil. In a 6-year period, OPEC cut their production basically in half, going from 32M barrels per day to just 14M barrels per day. This policy was costly for the OPEC countries and had unfavorable outcomes for the group. Other suppliers were able to increase their presence in the market, thus cutting away a big share of production from the group. On top of that, they underestimated the profitability of other sources of supply such as natural gas and nuclear power. It took them more than 20 years to get to the pre-glut production levels. To sum up, this price collapse benefited oil consuming countries (USA, Japan and Europe), but was extremely costly for oil-producing countries.

The biggest cut in production with a single announcement occurred in April 2020 in face of the Coronavirus pandemic. This event seriously threatened global stability, and it had foreseeable devastating consequences on the demand side for crude oil. The decision of OPEC was to cut production by 10M barrels per day. Despite this record cut (which in normal times would cause the price to skyrocket), oil prices still moved down because the market was afraid this was not

enough to offset this unprecedent demand loss. This unprecedented situation resulted in an equally unprecedented outcome, with the oil prices turning negative. This phenomenon was mainly a result of “storage risk”. The production cut was not enough to offset the sudden and persistent drop in demand, causing the storages to fill quickly and forcing oil tankers to become floating deposits. The market was ”not experienced and prepared for what was happening”.

None of these two historical examples of production cuts represented a risk for the global economy because they were simply adjustments on the supply side that resulted from shifts in the demand side. The rationale behind these decisions was to ensure price stability (even though it was not necessarily successful in either case). These types of adjustments of production levels are healthy dynamics for the market and they proved to be fairly successful in calming oil prices’ volatility. They are therefore fundamental instruments for OPEC to effectively fulfill its mission of providing market stability.

The cut we are seeing now might be different, even if it is a much smaller decrease in production of “just” 3.66M barrels per day. Saudi Arabia called it a “precautionary measure”, but the West did not like it. “Further squeezing already-tight supplies will be a slap in the face for consumers. The selfishly motivated move is aimed purely at benefiting producers,” Stephen Brennock, a senior analyst at PVM Oil Associates in London, said. The general sentiment is that this time OPEC is prioritizing higher prices instead of stability, worrying Washington. Ultimately, this decision seems a clear signal targeted towards the West, which is battling with an already tough inflation.

OPEC supply cut

Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” has given us one of the most indelible and haunting stories of the 20th century, imagining a world where control lies in the hands of a select few and where history is rewritten to fit the narrative of those in power. Similar to the power that The World Controllers hold in the book, OPEC+ has long controlled the oil supply of the world and, thus, the effects of its policies have visible consequences on all of the world’s economies.

OPEC+ is an alliance between the members of OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) and some of the large external oil-producers of the world. Together, OPEC+, that includes countries such as Saudi Arabia, Russia and Venezuela, controls more than half of the world’s petroleum exports and over 80% of its reserves. Needless to say, they hold immense economic and political power by strictly regulating the amount of oil produced, effectively operating as an economic cartel and have been known to leverage their power by adjusting the supply in their favor.

While in EMEA oil is not exactly scarce, it is important to note that the majority of it is concentrated in the Middle East and in Northern Africa, effectively leaving Europe (and especially the EU) with little to no oil of their own. Traditionally, the Europe has imported the oil it needed from Russia, the US, Norway (one of the very few European countries with significant oil reserves) and OPEC countries, but since the Russian-Ukrainian conflict has risen, most countries of the Old Continent have experienced supply chain issues, as they strived to cut Russian imports. This led to the “Energy crisis” that started in 2021, where Europe has had to find alternatives to the cheap Russian resources. This opportunity was exploited at its best by OPEC+, especially by Saudi Arabia, Libya and Kazakhstan, which became important trade partners of the EU at the expense of the Moscow government. However, this meant that the cartel now holds important leverage over the EU, and they made sure to make the most of it: despite the Western World’s diplomatic efforts (that sometimes actually resulted in promises by the cartel), OPEC+ has adjusted their output of oil however it pleased to, even as recently as April. But is this last alteration just another instance of the boy who cried wolf, a measure that lacks solid reasoning, or will OPEC+ defy the West and stick to their plans?

Economic outcome

The energy crisis has had a major impact on the supply chains and the macroeconomic stability of the world. High volatility in energy prices is a key component of many broad inflation indicators.

In EMEA, average inflation in 2021 was 2.9%, and reached a historical high of 9.2% in 2022, on account of the war in Ukraine and the exacerbation of energy issues.

Inflation in Europe has a different amplifying mechanism than in the United States, being driven largely by energy prices in the former, and largely by demand shocks in the latter.

The pandemic generated considerable supply chain stress exogenously, as many ports and other transit hubs were forced to reduce their capacity due to human contact restrictions. As these restrictions were eased, and on account of increased currency floating in the economy, especially in the United States, consumer demand rose sharply, especially for services, which put upward pressure on prices. Added to that was the rising cost of fuel for industry and for consumers as well, which made shipment more expensive and, subsequently, drove up the prices of the final goods and services available for sale.

The relationship between oil and the macroeconomy has been studied extensively. Historical evidence, especially from the two oil shocks which sent the United States into a period of high persistent inflation, would reasonably lead to the conclusion that the aforementioned relationship is strong. Generally, the current theoretical framework indicates that increases in oil prices reduce output. Moreover (Sill, 2007), the overall reduction of wealth in the economy results in decreased demand as well.

Consumption changes are not perfectly understood. For many years, economists believed that there was a clear difference between savings and consumption patterns between net importers and net exporters, which made price declines a net benefit for the world economy because gains by importers more than offset losses by exporters. It can reasonably be inferred that equity markets should perform in inverse correlation with price movements, as lower prices would lead to increased expected output, thus driving up stock valuations. However, as noted in research by the IMF (Obstfeld et.al., 2016), equity markets seem to be directly correlated with the direction of oil price movements. Therefore, the demand side of oil shocks remains subject to further research.

Recent academic findings on the Euro area (Holm-Hadulla, Hubrich, 2017) suggests the correlation between the macroeconomic indicators and oil shocks is stronger in “adverse regime”- that is, when oil prices increase. Inflation expectations were found to adjust similarly to oil price movements, but there was much higher upward sensitivity.

A look at the past

This is not the first time in history that OPEC has decided to cut the production of crude oil. In fact, the decision to manipulate the supply side of the market for oil is something that OPEC+ has done since its institution and this is not a particularly bad thing, per se. According to the OPEC website, their mission is “to coordinate and unify the petroleum policies of its Member Countries and ensure the stabilization of oil markets in order to secure an efficient, economic, and regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers, and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry.” This means that “manipulating” oil prices by interfering is part of their job with the aim of stabilizing prices without major fluctuations. They have intensively done so in the 80s during the so-called “1980s oil glut”. The energy crisis faced in the 70s caused a drop in demand that resulted in a major surplus of crude oil. In a 6-year period, OPEC cut their production basically in half, going from 32M barrels per day to just 14M barrels per day. This policy was costly for the OPEC countries and had unfavorable outcomes for the group. Other suppliers were able to increase their presence in the market, thus cutting away a big share of production from the group. On top of that, they underestimated the profitability of other sources of supply such as natural gas and nuclear power. It took them more than 20 years to get to the pre-glut production levels. To sum up, this price collapse benefited oil consuming countries (USA, Japan and Europe), but was extremely costly for oil-producing countries.

The biggest cut in production with a single announcement occurred in April 2020 in face of the Coronavirus pandemic. This event seriously threatened global stability, and it had foreseeable devastating consequences on the demand side for crude oil. The decision of OPEC was to cut production by 10M barrels per day. Despite this record cut (which in normal times would cause the price to skyrocket), oil prices still moved down because the market was afraid this was not

enough to offset this unprecedent demand loss. This unprecedented situation resulted in an equally unprecedented outcome, with the oil prices turning negative. This phenomenon was mainly a result of “storage risk”. The production cut was not enough to offset the sudden and persistent drop in demand, causing the storages to fill quickly and forcing oil tankers to become floating deposits. The market was ”not experienced and prepared for what was happening”.

None of these two historical examples of production cuts represented a risk for the global economy because they were simply adjustments on the supply side that resulted from shifts in the demand side. The rationale behind these decisions was to ensure price stability (even though it was not necessarily successful in either case). These types of adjustments of production levels are healthy dynamics for the market and they proved to be fairly successful in calming oil prices’ volatility. They are therefore fundamental instruments for OPEC to effectively fulfill its mission of providing market stability.

The cut we are seeing now might be different, even if it is a much smaller decrease in production of “just” 3.66M barrels per day. Saudi Arabia called it a “precautionary measure”, but the West did not like it. “Further squeezing already-tight supplies will be a slap in the face for consumers. The selfishly motivated move is aimed purely at benefiting producers,” Stephen Brennock, a senior analyst at PVM Oil Associates in London, said. The general sentiment is that this time OPEC is prioritizing higher prices instead of stability, worrying Washington. Ultimately, this decision seems a clear signal targeted towards the West, which is battling with an already tough inflation.

Political tensions

At first, the cut raised significant concern internationally. Tom Kloza, global head of energy analysis for the US Oil Price Information Service (a Dow Jones company that tracks gas prices for the national AAA) warns us that the OPEC’s move is “reawakening the inflation monster”. Furthermore, some experts believe that OPEC’s oil cut might increase international political tension between the USA, European countries, and the Middle East. Surprisingly, there is nomention of the cut in the “Joint Statement by the EU and the US following the 10th EU-US Energy Council”, which was published on April 4th by the European Commission.

However, after a couple of days, many economic newspapers started to refute the generalized panic. On April 4th the Financial Times published an article, boldly titled “OPEC isn’t scaring anyone”. As a matter of fact, oil prices will go up in the short term, and US and European central banks will be pressured by the spike in inflation, but the overall effect on the markets will result in being an “hypnotic effect”, said Robert Armstrong on the article. At the same time, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen believes that the cut’s effects will not be significant enough to make G7 countries reassess the price cap of $60 per barrel imposed on oil exported by Russia.

Then why did OPEC really decide to cut the oil production? Analysts have different opinions. Some believe simply it was a way to adjust the oil supply to the decrease in demand from Western countries.

Nevertheless, Armstrong states that the cut represents a strategic move, rather a way to “defend a weak oil price”. As Russian deputy prime minister Alexander Novak said, the Western (banking) system was an “interference with market dynamics”.

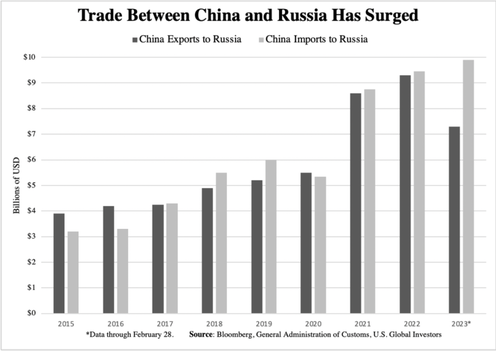

It appears that the reason of the cut is because oil-rich Middle East countries want to conquer the dominance of the petrol industry to the detriment of the US dollar, being oil the greatest (both in amount and value) commodity worldwide. It is no secret that the petrodollar has been facing major pressure by Eastern countries recently. The latest close relationship between China and Russia are just one example of the threats the US are facing in the oil market. Given the political barriers the latter has been facing ever since the invasion of Ukraine, Russia has turned its head towards its Asian neighbour, to create a new reserve currency. For instance, in late March 2023, President Vladimir Putin announced Russia would require “unfriendly” nations to purchase the country’s gas using Rubles exclusively. This resulted in the Russian currency spiking up against the petrodollar. Below is a graph representing China’s imports and exports to Russia, published by U.S. Global Investors.

At first, the cut raised significant concern internationally. Tom Kloza, global head of energy analysis for the US Oil Price Information Service (a Dow Jones company that tracks gas prices for the national AAA) warns us that the OPEC’s move is “reawakening the inflation monster”. Furthermore, some experts believe that OPEC’s oil cut might increase international political tension between the USA, European countries, and the Middle East. Surprisingly, there is nomention of the cut in the “Joint Statement by the EU and the US following the 10th EU-US Energy Council”, which was published on April 4th by the European Commission.

However, after a couple of days, many economic newspapers started to refute the generalized panic. On April 4th the Financial Times published an article, boldly titled “OPEC isn’t scaring anyone”. As a matter of fact, oil prices will go up in the short term, and US and European central banks will be pressured by the spike in inflation, but the overall effect on the markets will result in being an “hypnotic effect”, said Robert Armstrong on the article. At the same time, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen believes that the cut’s effects will not be significant enough to make G7 countries reassess the price cap of $60 per barrel imposed on oil exported by Russia.

Then why did OPEC really decide to cut the oil production? Analysts have different opinions. Some believe simply it was a way to adjust the oil supply to the decrease in demand from Western countries.

Nevertheless, Armstrong states that the cut represents a strategic move, rather a way to “defend a weak oil price”. As Russian deputy prime minister Alexander Novak said, the Western (banking) system was an “interference with market dynamics”.

It appears that the reason of the cut is because oil-rich Middle East countries want to conquer the dominance of the petrol industry to the detriment of the US dollar, being oil the greatest (both in amount and value) commodity worldwide. It is no secret that the petrodollar has been facing major pressure by Eastern countries recently. The latest close relationship between China and Russia are just one example of the threats the US are facing in the oil market. Given the political barriers the latter has been facing ever since the invasion of Ukraine, Russia has turned its head towards its Asian neighbour, to create a new reserve currency. For instance, in late March 2023, President Vladimir Putin announced Russia would require “unfriendly” nations to purchase the country’s gas using Rubles exclusively. This resulted in the Russian currency spiking up against the petrodollar. Below is a graph representing China’s imports and exports to Russia, published by U.S. Global Investors.

Economist Zoltar Pozsar labelled this nascent alliance as “the dusk for the petrodollar... and dawn for the petroyuan”.

What is more, in December 2022, during Chinese Prime Minister Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia, he claimed that China and the Arab Gulf “should make full use of the Shanghai Petroleum and National Gas Exchange [SHPGX] as a platform to carry out yuan settlement of oil and gas trades”, as reported by Reuters. Four months later, on March 28th, a SHPGX’sstatement stated that TotalEnergies SE, the French multinational belonging to the seven supermajor oil companies, had sold 65,000 tons of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), imported by the UAE.

Conclusion

So, is it time to bid farewell to the US dollar?

At the current fragile economic state of OPEC countries, especially Russia and China, experts are confident we are still far from reaching an utter “de-dollarization” of the oil market. All things considered, a yuan-dominated oil market is also challenged by the fact that, in the first half of 2022, just 2% of global imports and exports were traded in the Chinese currency. On the other hand, the dollar accounted for around 90% of trades worldwide. Lastly, American economist Jay Zagorsky from Boston University, claimed that international traders are not particularly appealed by the yuan or the ruble, because the investments might “get trapped inside a country” and investors “will be unable to move it out”.

By Dinu Cionga, Enrico Dametto, Matilde Chiavenato and Teodor Matei

What is more, in December 2022, during Chinese Prime Minister Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia, he claimed that China and the Arab Gulf “should make full use of the Shanghai Petroleum and National Gas Exchange [SHPGX] as a platform to carry out yuan settlement of oil and gas trades”, as reported by Reuters. Four months later, on March 28th, a SHPGX’sstatement stated that TotalEnergies SE, the French multinational belonging to the seven supermajor oil companies, had sold 65,000 tons of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), imported by the UAE.

Conclusion

So, is it time to bid farewell to the US dollar?

At the current fragile economic state of OPEC countries, especially Russia and China, experts are confident we are still far from reaching an utter “de-dollarization” of the oil market. All things considered, a yuan-dominated oil market is also challenged by the fact that, in the first half of 2022, just 2% of global imports and exports were traded in the Chinese currency. On the other hand, the dollar accounted for around 90% of trades worldwide. Lastly, American economist Jay Zagorsky from Boston University, claimed that international traders are not particularly appealed by the yuan or the ruble, because the investments might “get trapped inside a country” and investors “will be unable to move it out”.

By Dinu Cionga, Enrico Dametto, Matilde Chiavenato and Teodor Matei

Sources:

Financial Times

Reuters

Yahoo Finance

CNN

Oilprice.com

Business Insider

Financial Times

Reuters

Yahoo Finance

CNN

Oilprice.com

Business Insider