Palm oil represents the most used vegetal oil in the world and the 97th most traded good, with a business of 35 billion dollars.

For the top exporters, Indonesia($18.2B) and Malaysia($9.9B), we are talking about a key source of revenue; currently, the top importers are India($6.43B) and the European Union ($4.2B).

The 39% of imported oil in Europe is used for food, animal feed and products like cosmetics, as it’s one of the few vegetal fats with a high saturation, solid at room temperature and cheaper than butter or margarine.

A significant amount (51%) of palm oil is used instead to produce methyl ester and converted to biodiesels like the NEXBLT.

The remaining 10% is used in the soap industry, electricity and heating.

The business has come under fire in 2000, with the WWF Living Planet Report, in which emerged the issues of the cultivation in Malaysia: the impact on natural environment, including rampant deforestation, loss of natural habitats, destruction of wildlife, as well as increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Since then, many environmental associations focused on the Asian crops.

In 2004 the main producers and NGOs instituted The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to ethicize the supply chain, establishing international standards for the production and a specific trademark. Gaining the certification can be very expensive though, hence the demand of sustainable oil remained low (around 11%).

Indeed the effort was not appreciated by Greenpeace, who argued that RSPO standards flop protecting rain forests and reducing greenhouse gases.

In 2011 the critics shifted to health: Europe signed the Regulation No. 1169/2011 and from 2015 on food packaging the indication “vegetable fat” has been replaced by the type of vegetal origin. Simultaneously the European Authority for Alimentary Security discovered three toxic and carcinogenic substances in vegetal oils, but, despite the controversies, to this day there has been no evidence that palm oil contains more substances than others.

Once again in November 2016 Amnesty International published The great palm oil scandal, labor abuses behind big brand names, denouncing the forced employment of women, the minor exploiting and the indifference of multinationals, expecially the producers of cosmetics and snacks. The report is the result of an inquiry on Indonesian plantations of the greatest cropper in the world, Wilmar, which is also the supplier of 9 companies: AFAMSA, ADM, Colgate-Palmolive, Elevance, Kellogg’s, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser e Unilever.

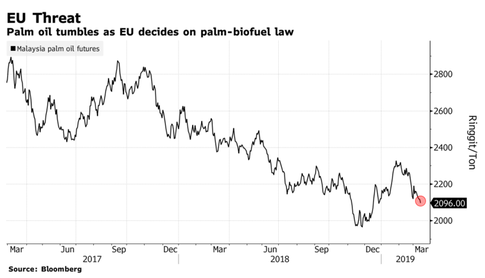

But the flashpoint of the conflict was the prohibition to use palm oil in biofuels voted by the European Parliament on the 17th January 2018. The EU Directive 2018/2001 implies that by 2021 palm oil will be replaced by renewable-energy sources like sun or wind.

On the 13th March 2019 the European Commission submitted a supplementing directive, announcing its complete removal by 2030. A gradual phase out will start in 2023 but from now it won’t be possible to increase the consumption. Instead, the use of other vegetal oils will go on, as the correlated damages on the ecosystem are considered lower (in 2008 the 45% of the palm crops provoked deforestation, against the 8% of soy and only 1% of rape and sunflower).

For the top exporters, Indonesia($18.2B) and Malaysia($9.9B), we are talking about a key source of revenue; currently, the top importers are India($6.43B) and the European Union ($4.2B).

The 39% of imported oil in Europe is used for food, animal feed and products like cosmetics, as it’s one of the few vegetal fats with a high saturation, solid at room temperature and cheaper than butter or margarine.

A significant amount (51%) of palm oil is used instead to produce methyl ester and converted to biodiesels like the NEXBLT.

The remaining 10% is used in the soap industry, electricity and heating.

The business has come under fire in 2000, with the WWF Living Planet Report, in which emerged the issues of the cultivation in Malaysia: the impact on natural environment, including rampant deforestation, loss of natural habitats, destruction of wildlife, as well as increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Since then, many environmental associations focused on the Asian crops.

In 2004 the main producers and NGOs instituted The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to ethicize the supply chain, establishing international standards for the production and a specific trademark. Gaining the certification can be very expensive though, hence the demand of sustainable oil remained low (around 11%).

Indeed the effort was not appreciated by Greenpeace, who argued that RSPO standards flop protecting rain forests and reducing greenhouse gases.

In 2011 the critics shifted to health: Europe signed the Regulation No. 1169/2011 and from 2015 on food packaging the indication “vegetable fat” has been replaced by the type of vegetal origin. Simultaneously the European Authority for Alimentary Security discovered three toxic and carcinogenic substances in vegetal oils, but, despite the controversies, to this day there has been no evidence that palm oil contains more substances than others.

Once again in November 2016 Amnesty International published The great palm oil scandal, labor abuses behind big brand names, denouncing the forced employment of women, the minor exploiting and the indifference of multinationals, expecially the producers of cosmetics and snacks. The report is the result of an inquiry on Indonesian plantations of the greatest cropper in the world, Wilmar, which is also the supplier of 9 companies: AFAMSA, ADM, Colgate-Palmolive, Elevance, Kellogg’s, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser e Unilever.

But the flashpoint of the conflict was the prohibition to use palm oil in biofuels voted by the European Parliament on the 17th January 2018. The EU Directive 2018/2001 implies that by 2021 palm oil will be replaced by renewable-energy sources like sun or wind.

On the 13th March 2019 the European Commission submitted a supplementing directive, announcing its complete removal by 2030. A gradual phase out will start in 2023 but from now it won’t be possible to increase the consumption. Instead, the use of other vegetal oils will go on, as the correlated damages on the ecosystem are considered lower (in 2008 the 45% of the palm crops provoked deforestation, against the 8% of soy and only 1% of rape and sunflower).

Malaysia and Indonesia grant the 85% of the global supply and they are already suffering of a shrinkage of consumptions in the food industry.

In the capital city of Kuala Lampur (MAL), hundreds of growers gathered to protest ahead of the UE decision. Seri Mah Siew Keong, the Malaysian Minister of Plantation Industries and Commodities, stated that the strict bloc will destroy the life of 3,2 million people, including 650.000 smallholders and farmers, in a country where many efforts have to be done to struggle against hunger and poverty.

The main criticism is that in Bruxelles no accuse was moved to other seed crops, excluding palm oil, so that the President of Indonesia Joko Widodo talks about “discrimination”.

The Indonesian Trade Minister, Enggartiasto Lukita called the move a “protectionist trade barrier” and a form of “crop apartheid” and together with the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries, joined also by Colombia, he is bringing an action before the WTO, accusing an obstruction to the freedom of exchange.

The two countries and Europe are at the loggerheads and a new trade world is likely to take place: Malaysia is retaliating against the plan by purchasing 250 new fighter jets form China instead of Airbus; the boycott was declared by the leader Mahatir Mohamad on the 24th March.

For the first time in the last 20 years the demand of palm oil will probably decrease, relying on the Reuters predictions. Other factors are the good harvest in India and the increasing amount of cheap soy, since the war of duties between USA and China made the prices fall.

At the Bursa Malaysia the benchmark price of palm oil fell to the minimum in the last 3 months (2.70 ringgit for ton) and it has dropped 18 percent since the start of 2018.

Silvia Guggiana

In the capital city of Kuala Lampur (MAL), hundreds of growers gathered to protest ahead of the UE decision. Seri Mah Siew Keong, the Malaysian Minister of Plantation Industries and Commodities, stated that the strict bloc will destroy the life of 3,2 million people, including 650.000 smallholders and farmers, in a country where many efforts have to be done to struggle against hunger and poverty.

The main criticism is that in Bruxelles no accuse was moved to other seed crops, excluding palm oil, so that the President of Indonesia Joko Widodo talks about “discrimination”.

The Indonesian Trade Minister, Enggartiasto Lukita called the move a “protectionist trade barrier” and a form of “crop apartheid” and together with the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries, joined also by Colombia, he is bringing an action before the WTO, accusing an obstruction to the freedom of exchange.

The two countries and Europe are at the loggerheads and a new trade world is likely to take place: Malaysia is retaliating against the plan by purchasing 250 new fighter jets form China instead of Airbus; the boycott was declared by the leader Mahatir Mohamad on the 24th March.

For the first time in the last 20 years the demand of palm oil will probably decrease, relying on the Reuters predictions. Other factors are the good harvest in India and the increasing amount of cheap soy, since the war of duties between USA and China made the prices fall.

At the Bursa Malaysia the benchmark price of palm oil fell to the minimum in the last 3 months (2.70 ringgit for ton) and it has dropped 18 percent since the start of 2018.

Silvia Guggiana