It was March 11 when the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the COVID-19 viral outbreak was officially a pandemic, the highest level of health emergency. Since then, the emergency has evolved into a global public health and economic crisis. PE firms are deploying different strategies to make the most of the opportunities generated by the crisis. Some managers are pivoting their companies into future growth and hibernating businesses with enough reserves, while others are cutting costs in order to remain afloat.

A recap of Covid-19 crisis

It was March 11 when the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the COVID-19 viral outbreak was officially a pandemic, the highest level of health emergency. Since then, the emergency has evolved into a global public health and economic crisis that has affected the global economy beyond anything experienced in nearly a century. The countries in which the virus has been detected are over 200. At the beginning of March 2020, the focal point of infections shifted from China, where it had first arisen, to Europe, especially in the north part of Italy. Nevertheless, by April the focus had shifted to the United States, where the number of infections was increasing day after day. The infection has sickened more than 40 million people with more than 1.1 million fatalities. In the middle of the pandemic, more than 80 countries had closed their borders to arrivals from countries which had reported cases of infections, ordered more-at-risk businesses to close and forced them to reinvent the way to get revenues in order to survive the crisis, instructed their populations to self-quarantine, and closed schools to an estimated 1.5 billion children.

The global pandemic is affecting economic and trade activities. Estimates so far point out that the pandemic could reduce global economic growth to a rate between -4.5% and -6.0% in 2020, with only a partial recovery of a rate between 2.5% and 5.2% in 2021. Such a negative effect on global economic growth was not experienced since at least the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. Nevertheless, while the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 primarily affected developed economies with highly advanced and inter-connected financial sectors, the COVID-19 pandemic is having a noticeable impact on both developed and developing economies, as clearly estimated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

After only one month since the first cases had been registered in the US, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that 20 million Americans lost their jobs in April 2020 because of business lockdowns, pushing the total number of unemployed Americans to 23 million. The increase pushed the national unemployment rate to 14.7%, the highest since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Lately, such a result has been partially relieved, as shown by a fall in the rate to 7.9%.

After providing $2.3 trillion in lending to support households, employers, financial market and both state and local governments, the Fed has cut its target for the federal funds rate by a total of 150 basis points since March 3rd, bringing it down to a range between 0 percent and 0.25 percent.

In Europe, governments attempted a phased business reopening over the summer, in an attempt to heal the damage inflicted to the economy by the shutdowns of the previous months. Nevertheless, after a period of data indicating an economic recovery had begun in the Eurozone, surveys of business activity in August reportedly pointed out that the rebound had slowed amid a new increase in COVID-19 cases and countries re-imposing new quarantines and lockdowns in various parts of the Euro area.

The European Commission’s (EC) forecast of mid-summer indicated that EU economic growth in 2020 could contract by 8.3% and only partially recover in 2021. As a consequence, after protracted talks, European leaders agreed on July 21 to support European economies with a new €750 billion economic assistance package. Indeed, estimates indicate that Eurozone’s countries could experience a combined budget deficit of nearly €1 trillion, equivalent to about 9% of their annual GDP. In addition, second quarter data pointed out that employment among EU countries has fallen by 2.6%, not considering the roughly 45 million people currently covered by employment protection programs.

Despite the massive and growing uncertainty, private equity (PE) firms are already adapting, looking for both ways to defend adversely affected areas of their portfolios and for new bets. Indeed, one truth about the pandemic is that it is accelerating existing trends, such as the digitalization of customer channels and workflows, and also giving rise to new ones, for instance real-time tracking and traceability.

Threats and opportunities for PE

PE firms are deploying different strategies to make the most out of the situation generated by the crisis. Some managers are directing their companies into future growth and hibernating businesses with enough reserves, while others are cutting costs in order to remain afloat and survive through the pandemic.

S&P Global, in a recent survey about expectations in the PE community, found out that the pandemic has had, and will continue to have, serious repercussions on PE activity. Nevertheless, the sentiment of PE managers varies significantly across regions.

A recap of Covid-19 crisis

It was March 11 when the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the COVID-19 viral outbreak was officially a pandemic, the highest level of health emergency. Since then, the emergency has evolved into a global public health and economic crisis that has affected the global economy beyond anything experienced in nearly a century. The countries in which the virus has been detected are over 200. At the beginning of March 2020, the focal point of infections shifted from China, where it had first arisen, to Europe, especially in the north part of Italy. Nevertheless, by April the focus had shifted to the United States, where the number of infections was increasing day after day. The infection has sickened more than 40 million people with more than 1.1 million fatalities. In the middle of the pandemic, more than 80 countries had closed their borders to arrivals from countries which had reported cases of infections, ordered more-at-risk businesses to close and forced them to reinvent the way to get revenues in order to survive the crisis, instructed their populations to self-quarantine, and closed schools to an estimated 1.5 billion children.

The global pandemic is affecting economic and trade activities. Estimates so far point out that the pandemic could reduce global economic growth to a rate between -4.5% and -6.0% in 2020, with only a partial recovery of a rate between 2.5% and 5.2% in 2021. Such a negative effect on global economic growth was not experienced since at least the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. Nevertheless, while the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 primarily affected developed economies with highly advanced and inter-connected financial sectors, the COVID-19 pandemic is having a noticeable impact on both developed and developing economies, as clearly estimated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

After only one month since the first cases had been registered in the US, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that 20 million Americans lost their jobs in April 2020 because of business lockdowns, pushing the total number of unemployed Americans to 23 million. The increase pushed the national unemployment rate to 14.7%, the highest since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Lately, such a result has been partially relieved, as shown by a fall in the rate to 7.9%.

After providing $2.3 trillion in lending to support households, employers, financial market and both state and local governments, the Fed has cut its target for the federal funds rate by a total of 150 basis points since March 3rd, bringing it down to a range between 0 percent and 0.25 percent.

In Europe, governments attempted a phased business reopening over the summer, in an attempt to heal the damage inflicted to the economy by the shutdowns of the previous months. Nevertheless, after a period of data indicating an economic recovery had begun in the Eurozone, surveys of business activity in August reportedly pointed out that the rebound had slowed amid a new increase in COVID-19 cases and countries re-imposing new quarantines and lockdowns in various parts of the Euro area.

The European Commission’s (EC) forecast of mid-summer indicated that EU economic growth in 2020 could contract by 8.3% and only partially recover in 2021. As a consequence, after protracted talks, European leaders agreed on July 21 to support European economies with a new €750 billion economic assistance package. Indeed, estimates indicate that Eurozone’s countries could experience a combined budget deficit of nearly €1 trillion, equivalent to about 9% of their annual GDP. In addition, second quarter data pointed out that employment among EU countries has fallen by 2.6%, not considering the roughly 45 million people currently covered by employment protection programs.

Despite the massive and growing uncertainty, private equity (PE) firms are already adapting, looking for both ways to defend adversely affected areas of their portfolios and for new bets. Indeed, one truth about the pandemic is that it is accelerating existing trends, such as the digitalization of customer channels and workflows, and also giving rise to new ones, for instance real-time tracking and traceability.

Threats and opportunities for PE

PE firms are deploying different strategies to make the most out of the situation generated by the crisis. Some managers are directing their companies into future growth and hibernating businesses with enough reserves, while others are cutting costs in order to remain afloat and survive through the pandemic.

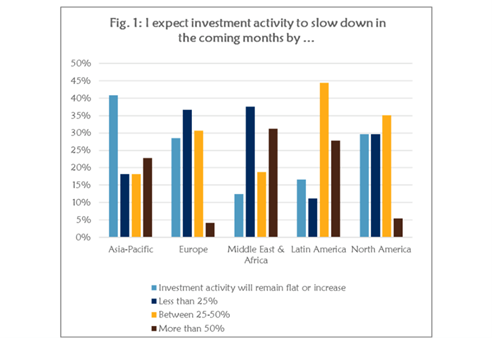

S&P Global, in a recent survey about expectations in the PE community, found out that the pandemic has had, and will continue to have, serious repercussions on PE activity. Nevertheless, the sentiment of PE managers varies significantly across regions.

Data as of 1/9/20. Source: PE Mid-Year Survey, S&P Global Market Intelligence

When it comes to future expectations, we can see from the chart that in the Asia-Pacific region the managers are more optimistic about their investment activity, while in all the other regions, activities are mostly believed to decrease. The main reason behind Asia-Pacific optimist is that the region was the first to be affected by the pandemic but also the first to recover. In the APAC region, roughly 40% of the respondents expect investment activities to remain flat or increase in the following months, whereas this percentage falls to below 30% in Europe and North America. The ones who are the most pessimistic about the near future are surely the PE managers from Middle East & Africa and Latin America, with the latter having around 70% of the respondents saying that investment activities will fall by more than 25%.

These answers can be easily linked to the present situation of the coronavirus in said regions, and to the way it was handled. The APAC region is slowly recovering from the crisis caused by the virus while, in all the other areas, governments are still struggling to contain it, and this consequently has significant repercussions on financial markets. Indeed, according to a report published by PitchBook, PE investments in the US decreased by almost 20% in the first half of the year to $326.7bn, when compared to the same time frame from one year prior.

This contrasts with data coming from the APAC region which, based on an analysis carried out by the Global Market division of S&P, saw an increase in PE and VC investments of 31% between the first and the second quarter of 2020.

These answers can be easily linked to the present situation of the coronavirus in said regions, and to the way it was handled. The APAC region is slowly recovering from the crisis caused by the virus while, in all the other areas, governments are still struggling to contain it, and this consequently has significant repercussions on financial markets. Indeed, according to a report published by PitchBook, PE investments in the US decreased by almost 20% in the first half of the year to $326.7bn, when compared to the same time frame from one year prior.

This contrasts with data coming from the APAC region which, based on an analysis carried out by the Global Market division of S&P, saw an increase in PE and VC investments of 31% between the first and the second quarter of 2020.

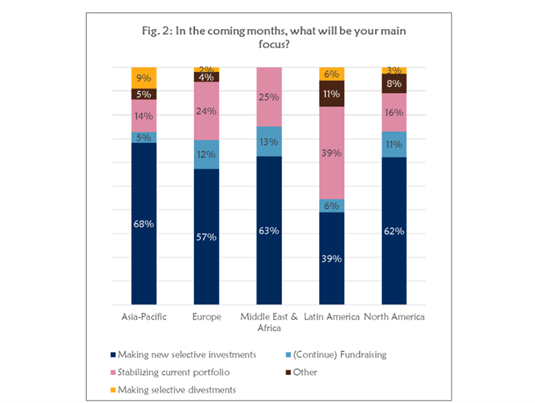

Data as of 1/9/20. Source: PE Mid-Year Survey, S&P Global Market Intelligence

The majority of the respondents, when asked about their main focus in the coming months, answered that they will be making new selective investments. In particular, distressed assets and special situations represent appealing targets.

The second most important concern among surveyed managers is about stabilizing their current portfolio, going from around 39% of them believing so in Latin America to 24% in Europe. Working on their current portfolio and remaining afloat during this difficult time is extremely important, even more so given that PE funds have about 50% of AUM in highly vulnerable sectors such as real estate, energy and utilities, logistics and travel and hospitality. Managers must therefore carefully consider the impact of the crisis on their holdings, and also keep track of the impact of the recent economic stimulus carried out by governments all around the world, especially stimulus programs that have provided liquidity to companies and assets whose underlying real performance may not be able to provide enough support and justify current valuations. They should work more on improving the solidity of their balance sheet and on a possible business model that can lead to a sustained future success by making profitable selective investments.

PE firms have been hit by the economic downturn, and this situation sparked some concerns about their reputation and their role in yet another global crisis. Indeed, many current private equity firms have seen and survived through these challenges before, during the global financial recession of 2007-08. In that occasion though, many PE funds, investors and managers stayed on the side-lines for too long and missed out on profitable opportunities created in those challenging times. This is the reason why, in this occasion, PE companies are intervening on the market earlier and are trying to take advantage of the situation in which the global economy happened to be.

An increasing number of companies and economic sectors are under severe pressure. Even firms who had a healthy balance sheet before the coronavirus hit, are now struggling to cope with the heavy losses they faced in the first half of the year. Millions of jobs have been lost, thousands of businesses closed, and more are still at risk, both in developing countries and in advanced economies. This is an extremely important situation in which PE have the ability to intervene. Firms which previously may not have been for sale, are now considering additional funding alternatives to shore up their cash position on their balance sheets. Private equity can bring capital, potentially preserving jobs (even if they are known and criticized for their massive layoffs when they take over a firm), restructuring debt, and helping managers to navigate their companies through the pandemic. To this respect, PE companies are collectively sitting on at least US$1.5 trillion of dry powder to help keep their existing portfolio companies going and potentially investing in firms suddenly in distress.

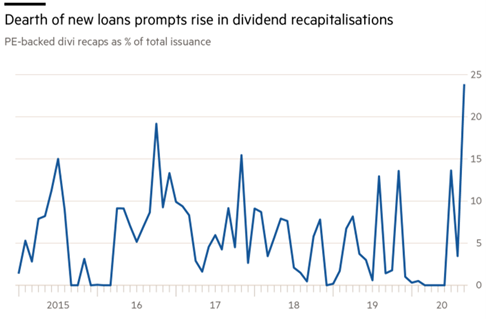

Moreover, given the accommodating monetary policies carried out by central banks around the world, the interest rate is now close to 0 in the US and in negative territory in the EU. This allows PE funds to issue cheap new debts through their holdings, in order to remain afloat during the crisis and to repay their investors through dividends. Indeed, in recent months, private equity groups including TPG and Apax Partners are issuing new debt in the companies they own and using the proceedings for dividend recapitalizations, that consist of paying a special dividend to their investors, funded with newly raised debt.

The second most important concern among surveyed managers is about stabilizing their current portfolio, going from around 39% of them believing so in Latin America to 24% in Europe. Working on their current portfolio and remaining afloat during this difficult time is extremely important, even more so given that PE funds have about 50% of AUM in highly vulnerable sectors such as real estate, energy and utilities, logistics and travel and hospitality. Managers must therefore carefully consider the impact of the crisis on their holdings, and also keep track of the impact of the recent economic stimulus carried out by governments all around the world, especially stimulus programs that have provided liquidity to companies and assets whose underlying real performance may not be able to provide enough support and justify current valuations. They should work more on improving the solidity of their balance sheet and on a possible business model that can lead to a sustained future success by making profitable selective investments.

PE firms have been hit by the economic downturn, and this situation sparked some concerns about their reputation and their role in yet another global crisis. Indeed, many current private equity firms have seen and survived through these challenges before, during the global financial recession of 2007-08. In that occasion though, many PE funds, investors and managers stayed on the side-lines for too long and missed out on profitable opportunities created in those challenging times. This is the reason why, in this occasion, PE companies are intervening on the market earlier and are trying to take advantage of the situation in which the global economy happened to be.

An increasing number of companies and economic sectors are under severe pressure. Even firms who had a healthy balance sheet before the coronavirus hit, are now struggling to cope with the heavy losses they faced in the first half of the year. Millions of jobs have been lost, thousands of businesses closed, and more are still at risk, both in developing countries and in advanced economies. This is an extremely important situation in which PE have the ability to intervene. Firms which previously may not have been for sale, are now considering additional funding alternatives to shore up their cash position on their balance sheets. Private equity can bring capital, potentially preserving jobs (even if they are known and criticized for their massive layoffs when they take over a firm), restructuring debt, and helping managers to navigate their companies through the pandemic. To this respect, PE companies are collectively sitting on at least US$1.5 trillion of dry powder to help keep their existing portfolio companies going and potentially investing in firms suddenly in distress.

Moreover, given the accommodating monetary policies carried out by central banks around the world, the interest rate is now close to 0 in the US and in negative territory in the EU. This allows PE funds to issue cheap new debts through their holdings, in order to remain afloat during the crisis and to repay their investors through dividends. Indeed, in recent months, private equity groups including TPG and Apax Partners are issuing new debt in the companies they own and using the proceedings for dividend recapitalizations, that consist of paying a special dividend to their investors, funded with newly raised debt.

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence

In September, almost 24% of the total money raised in the US loan market has been used for dividend recapitalizations, up from around 0% at the end of 2019 and early 2020. They have become common in the loan market in recent weeks, and this sparked concerns and worries among regulators around the world, since it is happening on top of an already highly leveraged historical time and amid what is the most volatile and uncertain economic period since the global financial crisis. An example of a company going through these dividend recapitalizations is Shearer’s Foods, owned by Chicago-based private equity company Wind Point Partners and the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, which issued over $1bn in fresh debts in September, and used $388m, i.e. more than 1/3 of the whole transaction, to repay its owners, according to the rating agency Moody’s.

In conclusion, it can be argued that the recent health crisis dealt a heavy blow to PE companies, especially those holding assets in vulnerable sectors, but it also created an environment for them to intervene strongly and decisively.

What can PE do to fasten recovery?

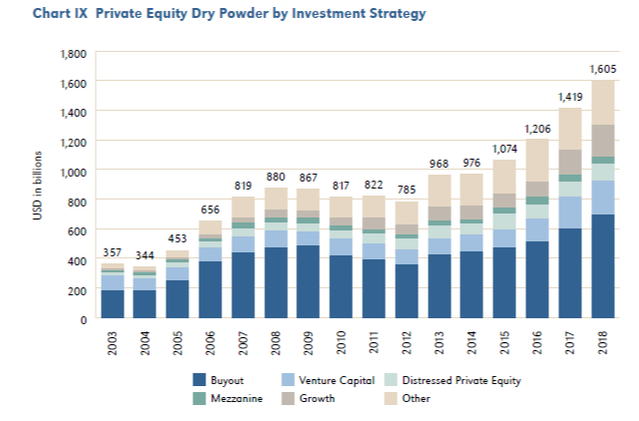

Covid-19 has triggered an M&A downcycle that - if compared to the previous three downcycles of 1990, 2001 and 2008 - is expected to last for about 2 years. While next months will display less deal counts, there are elements suggesting that this recovery should be faster than what experienced in the past. First, Covid-19 is an event-driven crisis, not structural or cyclical, which should recover much faster as it is triggered by a one-off shock. Moreover, private equity is likely to be significantly more active because of a USD 1.6 trillion amount of dry powder cumulated over the years (fig. 1) which forces partners to constantly look for attractive opportunities, supported by a competitive cost of capital and a stronger financing environment. Lastly, limited borrowing capabilities of banks are offset by a stronger role played by private debt funds which, seeking for higher returns, have started to provide acquisition financing for new deals.

In conclusion, it can be argued that the recent health crisis dealt a heavy blow to PE companies, especially those holding assets in vulnerable sectors, but it also created an environment for them to intervene strongly and decisively.

What can PE do to fasten recovery?

Covid-19 has triggered an M&A downcycle that - if compared to the previous three downcycles of 1990, 2001 and 2008 - is expected to last for about 2 years. While next months will display less deal counts, there are elements suggesting that this recovery should be faster than what experienced in the past. First, Covid-19 is an event-driven crisis, not structural or cyclical, which should recover much faster as it is triggered by a one-off shock. Moreover, private equity is likely to be significantly more active because of a USD 1.6 trillion amount of dry powder cumulated over the years (fig. 1) which forces partners to constantly look for attractive opportunities, supported by a competitive cost of capital and a stronger financing environment. Lastly, limited borrowing capabilities of banks are offset by a stronger role played by private debt funds which, seeking for higher returns, have started to provide acquisition financing for new deals.

Private Equity Dry Powder by Investment Strategy. Source: Preqin as of February 2019

ther than governments and central banks, Private Equity firms can contribute to a quick recovery by effectively putting their capital at work which is why it is important they do not stay on the sidelines for too long as it happened in 2008. Indeed, the competitive landscape in private equity is about to be reshaped and winners will be those able to size the opportunities rather than waiting for things to calm down.

So, what else should we expect?

Even if companies had healthy capital structure before the crisis, most of them have been strongly affected because of decreased profitability due to Covid-19 and it has been necessary to amend their bank covenants or restructure their debt to avoid the worst scenario. This has weakened the capital structure of many targets that Private Equity players could not afford in the past. Now, the same targets may be considering alternative financing sources. Distressed Private Equity can bring capital to the table, also incentivised by cheaper valuations. The sectors facing the strongest liquidity and WC shortfalls and that may attract significant attention from sponsors are retail, accommodation and food services.

In the short term, it is reasonable to expect social factors to weight more heavily. Boards, management teams and regulators are expected to be highly focused on preserving employment and defending national champions which requires to be sensitive about timing and the aggressiveness of the approach. Therefore, small deals are likely to drive initial deal count volume as they are less supervised by regulators, less dependent on external financing and therefore less exposed to the tightening of the credit market. Moreover, given the increased attention of regulators to protect national assets, cross-border M&A challenges are expected to worsen.

Lastly, judgement is becoming more critical than ever. Given the uncertainty around the duration of the crisis and potential long-term structural changes, valuation challenges are becoming increasingly complex and most of it is left to the strategic intuition of the sponsor.

A special focus on infrastructure

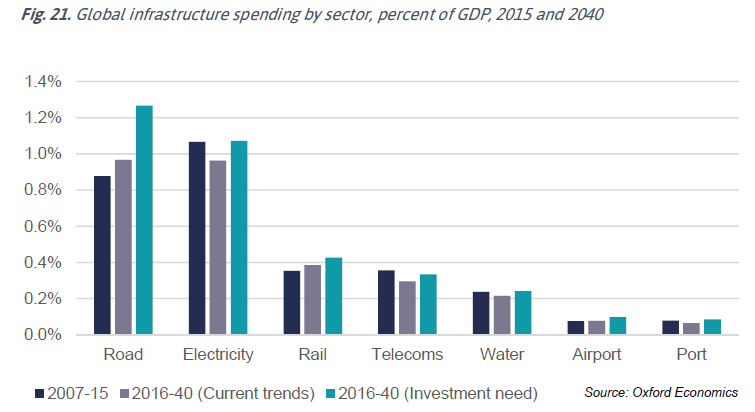

The Covid-19 crisis has further accentuated the increasing focus that sponsors have for infrastructure investments as it has opened up larger investment gaps to deliver on the green transition and digital transformation. Most governments have supported recovery from Covid-19 through unprecedented fiscal policies (USD 5.5 trillion in the US). However, spending is going to be prioritized with a focus on forgivable loans to small businesses, tax credits and fiscal support to local governments. This has inevitably shifted public resources away from infrastructure projects as emergencies imply short-termism in public intervention. Given the already existing significant gap between investment needs and available resources forecasted for future years (especially for road and electricity, see Fig.2), larger gaps from lower public investments create more opportunities to attract investments from financial sponsors.

So, what else should we expect?

Even if companies had healthy capital structure before the crisis, most of them have been strongly affected because of decreased profitability due to Covid-19 and it has been necessary to amend their bank covenants or restructure their debt to avoid the worst scenario. This has weakened the capital structure of many targets that Private Equity players could not afford in the past. Now, the same targets may be considering alternative financing sources. Distressed Private Equity can bring capital to the table, also incentivised by cheaper valuations. The sectors facing the strongest liquidity and WC shortfalls and that may attract significant attention from sponsors are retail, accommodation and food services.

In the short term, it is reasonable to expect social factors to weight more heavily. Boards, management teams and regulators are expected to be highly focused on preserving employment and defending national champions which requires to be sensitive about timing and the aggressiveness of the approach. Therefore, small deals are likely to drive initial deal count volume as they are less supervised by regulators, less dependent on external financing and therefore less exposed to the tightening of the credit market. Moreover, given the increased attention of regulators to protect national assets, cross-border M&A challenges are expected to worsen.

Lastly, judgement is becoming more critical than ever. Given the uncertainty around the duration of the crisis and potential long-term structural changes, valuation challenges are becoming increasingly complex and most of it is left to the strategic intuition of the sponsor.

A special focus on infrastructure

The Covid-19 crisis has further accentuated the increasing focus that sponsors have for infrastructure investments as it has opened up larger investment gaps to deliver on the green transition and digital transformation. Most governments have supported recovery from Covid-19 through unprecedented fiscal policies (USD 5.5 trillion in the US). However, spending is going to be prioritized with a focus on forgivable loans to small businesses, tax credits and fiscal support to local governments. This has inevitably shifted public resources away from infrastructure projects as emergencies imply short-termism in public intervention. Given the already existing significant gap between investment needs and available resources forecasted for future years (especially for road and electricity, see Fig.2), larger gaps from lower public investments create more opportunities to attract investments from financial sponsors.

Global infrastructure spending by Sector, percentage of GDP. Source: Oxford Economics

However, sponsors and governments have very different utility functions as the former aim at maximising IRRs while the latter include positive externalities for the entire economy in the assessment of the attractiveness of an investment. Hence, despite private money cannot replace all public money, there are for sure additional opportunities for sponsors, especially in the riskiest infrastructure projects (known as “value added”) which covers sectors as telecom for the development of the 5G network and data centres.

To allow sponsors to invest their capital in infrastructure while aiming at achieving a high IRR (say, 20%), other players must participate in the financing of the project to achieve an optimal level of leverage. Indeed, such investments are known as DIY as they are diversified (D), inflation protected (I), and produce stable yield (Y) because of low demand elasticity. Such characteristics of this asset class are not in line with benchmark IRRs if leverage is not sufficiently exploited. This is why creditors (private debt funds, sovereign pension plans and insurance companies) looking for long term and stable yield play a role in infrastructure financing.

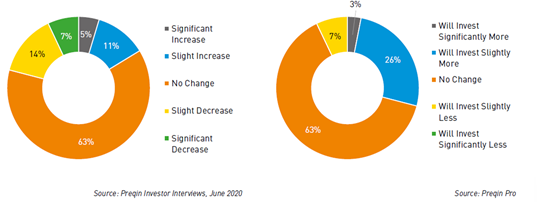

In addition to this, covid-19 has had a limited impact on future expected commitments to infrastructure projects. As shown in Fig. 3 financial sponsors responding to the survey confirm that they do not expect to decrease the capital they intend to allocate in infrastructure nor in the short nor in the long term.

To allow sponsors to invest their capital in infrastructure while aiming at achieving a high IRR (say, 20%), other players must participate in the financing of the project to achieve an optimal level of leverage. Indeed, such investments are known as DIY as they are diversified (D), inflation protected (I), and produce stable yield (Y) because of low demand elasticity. Such characteristics of this asset class are not in line with benchmark IRRs if leverage is not sufficiently exploited. This is why creditors (private debt funds, sovereign pension plans and insurance companies) looking for long term and stable yield play a role in infrastructure financing.

In addition to this, covid-19 has had a limited impact on future expected commitments to infrastructure projects. As shown in Fig. 3 financial sponsors responding to the survey confirm that they do not expect to decrease the capital they intend to allocate in infrastructure nor in the short nor in the long term.

Investors’ Views on the Impact of Covid-19 on the Size of Their Planned Commitments to Infrastructure in 2020 and Over the Long-Term. Source: Preqin Investor Interviews, June 2020

Indeed, infrastructure is the perfect trade off to keep generating high returns while looking for a defensive asset class. It targets essential services that preserve stable demand over time, involves natural monopolies with high entry barriers and remuneration is often highly regulated by the government. There is little that Covid-19 can do to damage the stable cashflows of an already operating infrastructure project.

Our Key Takeaways

Analysts

Our Key Takeaways

- With the global pandemic having adverse effects on all major macroeconomic’ indicators to an extent comparable to that of the GFC of 2008 and 2009, M&A activity is expected to inevitably slowdown in 2020.

- Sentiment of PE managers varies significantly across regions, as investments are expected to remain stable or increase in APAC while investment activity will slow down in EMEA and Americas coherently with the temporal evolution of the pandemic.

- What is sure is that this time PE managers can play a significant role to fasten recovery by putting their c. USD 1,6 trillion dry powder at work, attracted by the pandemic’s adverse impact on valuations of certain sectors such as travel, hospitality and retail.

- Given the shift away of government spending from infrastructure financing, we identify an attractive opportunity for financial sponsors to mitigate such funding gap and to boost activity in value added projects such as 5G development and data centres

Analysts

- Alessandro Maraldi

- Antonio Wang

- Nicola Bulgarelli