The theme of investing in the “real economy” is a very timely one. The Italian government has addressed this issue by introducing the so-called “PIR”, Piani Individuali di Risparmio (Individual investment Plans), by means of the law No 232 of December 2016.

A PIR can be seen as a “container” of financial instruments (equity, bonds, funds, life insurance’s shares…), which allows the investor to be exempted from taxation on capital gains and other accruing income as well as from inheritance taxes.

According to the provision, the PIR must meet a series of requirements for it to benefit of the above-mentioned conditions. Not only can each physical person own at most one PIR, but the investment should also be maintained for a minimum of 5 years and the maximum amount that can be invested is 150 thousand euros (that is 30 thousand annually).

Moreover, and that’s the interesting part, the 70% of the investment should be in securities issued by companies with “stable organization” in Italy and the 21% of the total should be in securities of companies not belonging to the FTSE MIB index, in order to boost inflows into medium-sized and smaller companies.

The coming months promise to be particularly “hot” for these instruments. Over the first half of the year, the PIR that have been launched on the market by several asset management companies (around 50) have collected around 5 billion euros, and the amount is estimated to rise to 10 billion by the end of 2017. A figure well above the initial cautious prospect of the Italian government, which forecasted a collection of about 2 billion in the first year of activity of the PIR.

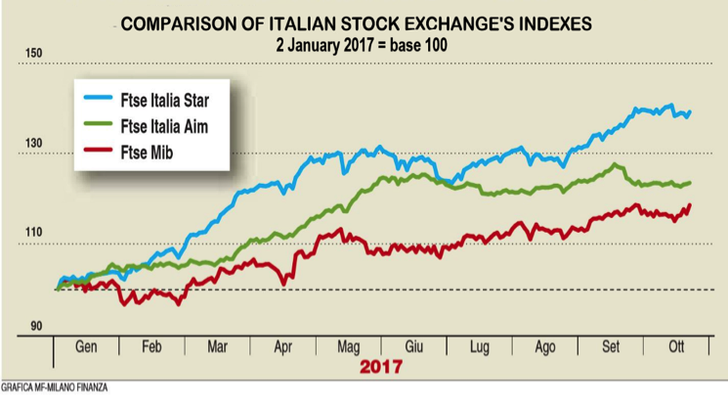

Furthermore, the PIR has been partly held responsible for the acceleration of the Italian Stock Exchange during the current year, especially regarding the segments relative to firms of smaller size. It is sufficient to confront the positive variation of 18% of the FTSE

MIB, the index of the Italian blue chips, with the 22% of the FTSE AIM, the 34% of the FSE ITALIA MID CAP up to the 38% of the index

relative to the STAR segment.

“The PIR are the leverage needed to give a push to the Italian financial market, that up to now has not completely interpreted the role of intermediary between private capital and firms” says Ennio Doris, president of Banca Mediolanum, enthusiastic supporter of the instrument.

According to Mr Doris, the Italian financial market has always characterized itself as a bank-centred system, with its pros and its cons. The Italian lending institutions have not always financed the firms really deserving it and too often financing has been tied to interests of other nature.

The key objective is to make use of all the liquidity collected through the PIR to offer an alternative to bank financing to the medium and small-sized firms, traditionally squeezed off to a corner of the financial markets. According to Mr Doris, the market, in its search for diversified investment opportunities, is able to support them, underwriting their bond and even share issues. The full relevance of this goal can be only understood considering that small mid-cap companies indeed are the backbone of the Italian economy.

For this to happen, the challenge for the coming months takes place on the offer side of the market: as Mr Doris underlines, the great popularity of these instruments becomes pointless, if there are just a few companies benefiting from the capital raised.

The most straightforward way to increase the offer is to incentivize the listing of small medium-sized companies. Legislation seems to move in the right direction: a tax credit of 50% on advisory costs sustained for an IPO is awaited in 2018. Being costs the main obstacle to the IPO of a small company, this provision is expected to lead to the listing of about 60 newcomers on the AIM next year.

The PIR are clearly instruments that, despite being at the initial stages of their development, show a huge, unexpected success. The premises are thrilling and next few months will be crucial in determining whether a wise regulation will enable them to effectively bring about a Copernican revolution in the Italian financial market.

Giacomo Longoni

A PIR can be seen as a “container” of financial instruments (equity, bonds, funds, life insurance’s shares…), which allows the investor to be exempted from taxation on capital gains and other accruing income as well as from inheritance taxes.

According to the provision, the PIR must meet a series of requirements for it to benefit of the above-mentioned conditions. Not only can each physical person own at most one PIR, but the investment should also be maintained for a minimum of 5 years and the maximum amount that can be invested is 150 thousand euros (that is 30 thousand annually).

Moreover, and that’s the interesting part, the 70% of the investment should be in securities issued by companies with “stable organization” in Italy and the 21% of the total should be in securities of companies not belonging to the FTSE MIB index, in order to boost inflows into medium-sized and smaller companies.

The coming months promise to be particularly “hot” for these instruments. Over the first half of the year, the PIR that have been launched on the market by several asset management companies (around 50) have collected around 5 billion euros, and the amount is estimated to rise to 10 billion by the end of 2017. A figure well above the initial cautious prospect of the Italian government, which forecasted a collection of about 2 billion in the first year of activity of the PIR.

Furthermore, the PIR has been partly held responsible for the acceleration of the Italian Stock Exchange during the current year, especially regarding the segments relative to firms of smaller size. It is sufficient to confront the positive variation of 18% of the FTSE

MIB, the index of the Italian blue chips, with the 22% of the FTSE AIM, the 34% of the FSE ITALIA MID CAP up to the 38% of the index

relative to the STAR segment.

“The PIR are the leverage needed to give a push to the Italian financial market, that up to now has not completely interpreted the role of intermediary between private capital and firms” says Ennio Doris, president of Banca Mediolanum, enthusiastic supporter of the instrument.

According to Mr Doris, the Italian financial market has always characterized itself as a bank-centred system, with its pros and its cons. The Italian lending institutions have not always financed the firms really deserving it and too often financing has been tied to interests of other nature.

The key objective is to make use of all the liquidity collected through the PIR to offer an alternative to bank financing to the medium and small-sized firms, traditionally squeezed off to a corner of the financial markets. According to Mr Doris, the market, in its search for diversified investment opportunities, is able to support them, underwriting their bond and even share issues. The full relevance of this goal can be only understood considering that small mid-cap companies indeed are the backbone of the Italian economy.

For this to happen, the challenge for the coming months takes place on the offer side of the market: as Mr Doris underlines, the great popularity of these instruments becomes pointless, if there are just a few companies benefiting from the capital raised.

The most straightforward way to increase the offer is to incentivize the listing of small medium-sized companies. Legislation seems to move in the right direction: a tax credit of 50% on advisory costs sustained for an IPO is awaited in 2018. Being costs the main obstacle to the IPO of a small company, this provision is expected to lead to the listing of about 60 newcomers on the AIM next year.

The PIR are clearly instruments that, despite being at the initial stages of their development, show a huge, unexpected success. The premises are thrilling and next few months will be crucial in determining whether a wise regulation will enable them to effectively bring about a Copernican revolution in the Italian financial market.

Giacomo Longoni