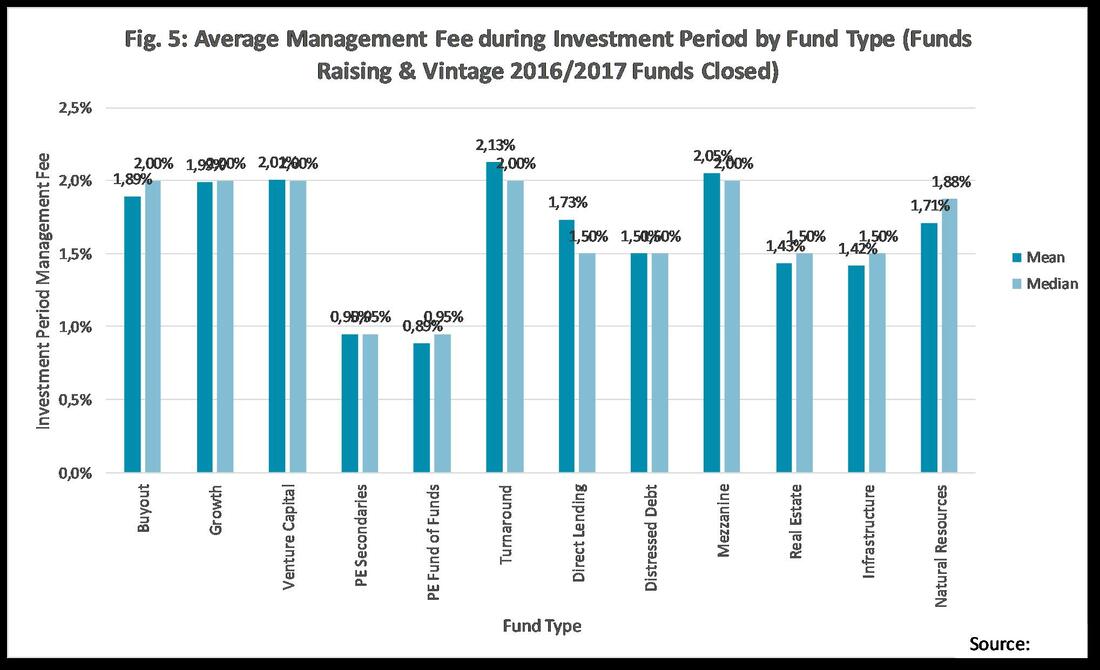

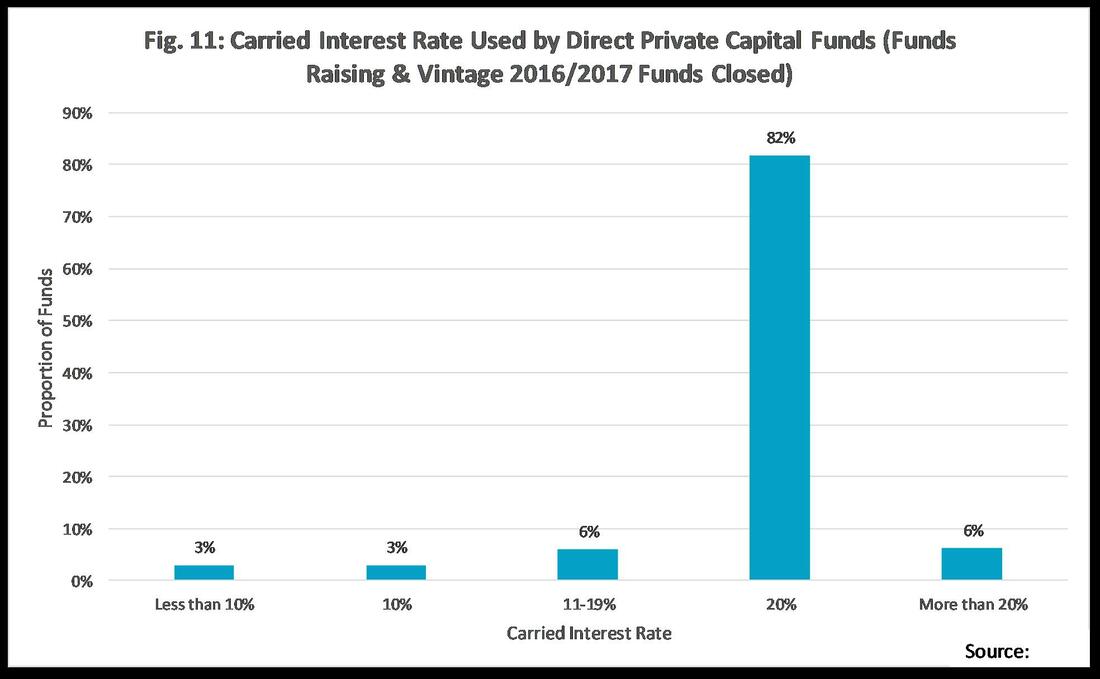

Some of the biggest Private Equity funds, so called Buyout or LBO funds, have started to increase the performance fees they charge investors well above the industry standard level. In the Private Equity industry, General Partners (GP or MCO) receive two forms of compensation, namely management fee and carried interest. As a rule of thumb, it has been the consolidated norm in the industry the so called 2/20 rule, meaning 2% management fee and 20% carried interest on the over-performance of the investment (with or without hurdle rate and catch-up clause), as it can be observed in the graphs below.

However, at a time when institutional investors are competing to allocate their pool of liquidity available into the best vehicles, some investors are paying as much as 30% carried interests to the biggest funds. An impressive increase of fifty percent, if compared to the 20% that has been the standard for decades. Although in some cases this increase is somehow counterbalanced by a reduction in management fee, this shows an overall rebalancing of power in favor of PE funds.

This trend has arrived this year in Europe, coming from overseas. In fact, the first PE Groups to launch high-end carried interest funds have been US giants like Carlyle Group, Vista Equity Partners, and Bain Capital. European names such as Eurazeo and Altor did not wait a long time to follow their American peers. This phenomenon is principally due to the huge pool of liquidity available and ready to be injected into funds, and some fund managers hence are taking advantage of the situation in order to improve their contractual power.

A previous increase in carried interest took place also at the beginning of the 2008 financial crisis, followed by an obvious reduction as soon as funds faced the consequences of the crisis, and liquidity problems arised. According to Prequin Buyout groups, the biggest and most powerful groups in the PE industry, take now on average no more than just a year to fundraise their activities. Thus representing an impressive half cut in time, if compared to the post-crisis figures. In addition, some funds also cut so called early-bid discounts, as investors fear they could be excluded from important funds in a low rate environment with fewer alternative investments opportunities available.

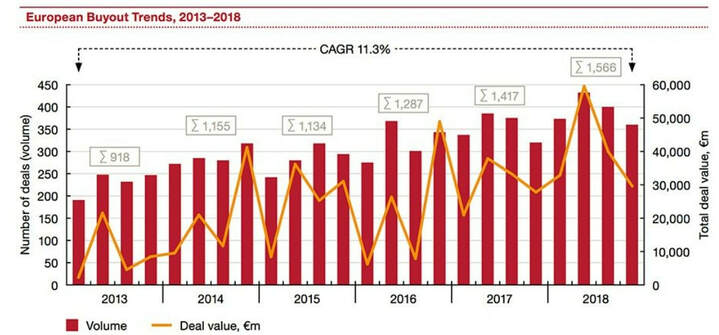

In Europe, according to PwC reports, financial investors have increased their activities in buying and selling enterprises, and the activities registered went back for the first time to pre-crisis figures. However, across Europe’s constituent national markets, the uplift was entirely driven by buyouts rather than exits. A total of 1,566 transactions were made, representing an annual increase of 11% to set yet a new post-crisis record. On a value basis, buyouts surged by 25% year-on-year to €175 billion, again the highest figure since the global financial crisis, as there was a stronger weighting towards larger deals.

This trend has arrived this year in Europe, coming from overseas. In fact, the first PE Groups to launch high-end carried interest funds have been US giants like Carlyle Group, Vista Equity Partners, and Bain Capital. European names such as Eurazeo and Altor did not wait a long time to follow their American peers. This phenomenon is principally due to the huge pool of liquidity available and ready to be injected into funds, and some fund managers hence are taking advantage of the situation in order to improve their contractual power.

A previous increase in carried interest took place also at the beginning of the 2008 financial crisis, followed by an obvious reduction as soon as funds faced the consequences of the crisis, and liquidity problems arised. According to Prequin Buyout groups, the biggest and most powerful groups in the PE industry, take now on average no more than just a year to fundraise their activities. Thus representing an impressive half cut in time, if compared to the post-crisis figures. In addition, some funds also cut so called early-bid discounts, as investors fear they could be excluded from important funds in a low rate environment with fewer alternative investments opportunities available.

In Europe, according to PwC reports, financial investors have increased their activities in buying and selling enterprises, and the activities registered went back for the first time to pre-crisis figures. However, across Europe’s constituent national markets, the uplift was entirely driven by buyouts rather than exits. A total of 1,566 transactions were made, representing an annual increase of 11% to set yet a new post-crisis record. On a value basis, buyouts surged by 25% year-on-year to €175 billion, again the highest figure since the global financial crisis, as there was a stronger weighting towards larger deals.

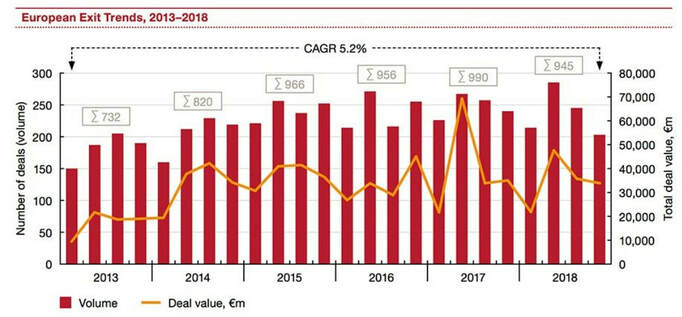

As far as exits, numbers speak differently. Last year registered 845 company sales in Europe, worth a combined €139 billion. This represents annual falls of -4.5% and -13.1% respectively, and the weakest exit activity since 2014.

However, although in this positive environment especially large funds are showing positive signals to the market, some analysts believe a possible bubble is about to burst. In London, the European Financial hub, Real Estate proprieties market values are on average 5% lower than they were two years ago, according to Nationwide. As a consequence, the Private Equity market as well is starting to show some signs of potential distress. UK retail industry is suffering from online-businesses strong competition, and many food chains such as PizzaExpress and Byron have encountered problems and are struggling partly because of the high-yield debt as a consequence of Private Equity ownership.

In continental Europe, the business model of Private Equity investors has been so successful also due to favorable macroeconomic conditions. Low interest rates, quantitative easing and bullish stock markets able to provide PE funds with a juicy exit opportunity (i.e. IPO). The business model of Private Equity funds, buying cheap companies, cutting costs, leveraging with cheap debt has been able to provide limited partners with significant returns and attract many institutional investors.

In continental Europe, the business model of Private Equity investors has been so successful also due to favorable macroeconomic conditions. Low interest rates, quantitative easing and bullish stock markets able to provide PE funds with a juicy exit opportunity (i.e. IPO). The business model of Private Equity funds, buying cheap companies, cutting costs, leveraging with cheap debt has been able to provide limited partners with significant returns and attract many institutional investors.

|

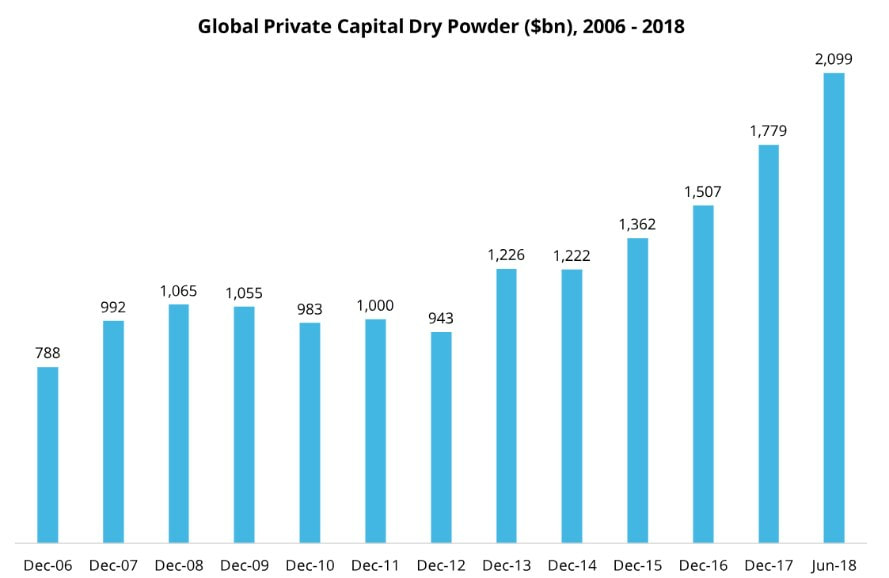

However, in a part of the financial community there is a belief that the PE industry is soon to become a victim of its own success. In fact, the amount of dry powder (funding that has already but is yet to be invested by funds) skyrocketed to $2tn, as of June 2018. Europe-focused dry powder alone has increased significantly as well, totaling as much as a quarter of the global amount. Looking by asset classes, the previous trend has been reversed, and starting from 2013 Private Equity now accounts for some 60% of the total global dry powder. This is due to the fact that so many pension funds, private wealth management funds and sovereign funds want their significant slice in the Private Equity investments activities, and PE funds are receiving more and more funding.

|

Private Equity funds are now fighting each other in order to secure the best investments, and as a consequence of the classic supply-demand dynamic, prices are increasing, hence making the classic “buy cheap sell high” approach more difficult. As an example, a consortium of Hellmann & Friedman and Blackstone has acquired with an impressive 27 per cent premium German online advertiser Scout24. In order to finance their acquisitions, PE funds are leveraging on a massive amount of debt, and the ratio of total debt over profit is increasing on a year-by-year basis.

With entering multiples already high, arbitrage strategies (i.e. selling at higher multiples due to market appetite) seem more difficult to be implemented in the future. Buyout groups are now paying on average 17 times earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (Ebitda) for their target companies, compared with 14 times Ebitda in 2017, according to Dealogic. In this context, the growing competition is increasing the likelihood going forward of generating lower returns for those PE funds that focus their efforts in arbitrage opportunities following a so called hands-off approach.

In addition, also the possible rise in interest rates is putting pressure on PE funds. Especially considering the fact that leverage for buyouts has increased to almost 7 times Ebitda, the highest level since 2014 (according to Refinitiv data). At the same time, the percentage of cash in buyout transactions has fallen to less than 40 per cent.

All eyes are on funds ability to successfully increase revenue and/or cut costs, and implement synergies. In this environment, the funds that are more likely to thrive will be those funds which, following a hands-on approach, will be able to work close with firms’ management teams and guarantee long term value-creation for the investors. In fact, while it is unlikely that in Europe there will be shortage of companies to acquire since the ration of PE investments over GDP is still low (and Italy is in this sense a good example), the real challenge will be finding the right companies to invest in and at fair valuation prices. This might generate better results in terms of both IRR and cash-on-cash multiples especially for funds with a proven track of successful acquisitions and growth strategies implementations. This is a sign of the transformation of the overall industry, which needs to continue to adapt and implement its value creation purpose in more innovative ways.

According to some analysts, however, if bad recession forecasts materialize, overpriced Private Equity acquisitions could turn into negative equity. Another important reason for PE funds to focus on less showy but more resilient and flexible companies. Italy, in this context, might represent a good example since it is home to a pool of strong proven SMEs that might have a certain lack of managerial skills and financial resources in order to grow and expand.

The Private Equity industry might soon face some challenges, rising interest rates, generalized slowing economic growth in Europe, scarcity in fair investment opportunities and possibly tougher market conditions. However, due to the still low penetration of PE investments in Europe and the consequent room for growth, the fact that PE firms in the aggregate still pay less than the public markets, and due to the fact that the industry is still managing to deploy capital at a record rate, we can in conclusion say that Private Equity is hot, but not yet overheating.

Francesco Spagnolo

With entering multiples already high, arbitrage strategies (i.e. selling at higher multiples due to market appetite) seem more difficult to be implemented in the future. Buyout groups are now paying on average 17 times earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (Ebitda) for their target companies, compared with 14 times Ebitda in 2017, according to Dealogic. In this context, the growing competition is increasing the likelihood going forward of generating lower returns for those PE funds that focus their efforts in arbitrage opportunities following a so called hands-off approach.

In addition, also the possible rise in interest rates is putting pressure on PE funds. Especially considering the fact that leverage for buyouts has increased to almost 7 times Ebitda, the highest level since 2014 (according to Refinitiv data). At the same time, the percentage of cash in buyout transactions has fallen to less than 40 per cent.

All eyes are on funds ability to successfully increase revenue and/or cut costs, and implement synergies. In this environment, the funds that are more likely to thrive will be those funds which, following a hands-on approach, will be able to work close with firms’ management teams and guarantee long term value-creation for the investors. In fact, while it is unlikely that in Europe there will be shortage of companies to acquire since the ration of PE investments over GDP is still low (and Italy is in this sense a good example), the real challenge will be finding the right companies to invest in and at fair valuation prices. This might generate better results in terms of both IRR and cash-on-cash multiples especially for funds with a proven track of successful acquisitions and growth strategies implementations. This is a sign of the transformation of the overall industry, which needs to continue to adapt and implement its value creation purpose in more innovative ways.

According to some analysts, however, if bad recession forecasts materialize, overpriced Private Equity acquisitions could turn into negative equity. Another important reason for PE funds to focus on less showy but more resilient and flexible companies. Italy, in this context, might represent a good example since it is home to a pool of strong proven SMEs that might have a certain lack of managerial skills and financial resources in order to grow and expand.

The Private Equity industry might soon face some challenges, rising interest rates, generalized slowing economic growth in Europe, scarcity in fair investment opportunities and possibly tougher market conditions. However, due to the still low penetration of PE investments in Europe and the consequent room for growth, the fact that PE firms in the aggregate still pay less than the public markets, and due to the fact that the industry is still managing to deploy capital at a record rate, we can in conclusion say that Private Equity is hot, but not yet overheating.

Francesco Spagnolo