Earlier this week, Procter & Gamble [NYSE: PG] reached an agreement with German pharmaceutical giant Merck KGaA to acquire the latter’s consumer health business for €3.4 billion in an all-cash deal. The acquisition would enable the American consumer goods company to expand its portfolio of consumer-health products, amid difficult times marked by fierce competition and decreasing gross margins across the more discretionary product categories. Perhaps even more interesting is the fact that P&G as we know it today is not the typical acquirer, having spent around 8 years focusing only on organic growth and divestitures, during a tough turnaround process that has yet to provide significant results to shareholders.

Procter & Gamble has divested significantly over the decade, aiming to streamline its operations to the most profitable brands. In recent years, the company sold around 100 of its brands, while keeping only the remaining 65, split into 10 product categories. In 2015, a $12.5 billion transaction for the license to market a large portfolio of cosmetics brands including Gucci and Hugo Boss pulled P&G away from the Perfumes industry. In the following year P&G sold famous batteries manufacturer Duracell to Berkshire Hathaway, as Warren Buffet cleverly exchanged his P&G shares to avoid a major tax burden. However, the firm’s strategy has suffered a clear change recently, as management believes that increasing revenues through faster-growing products is crucial to sustain growth and competitiveness in the long term. Acquisitions can put the company on a fast track to reach this goal.

The relatively small acquisition in November 2017 of the San Francisco-based deodorant brand Native Deodorant for $100 million in cash serves as a clear example, given that P&G already owned the popular brand Secret operating in the same market. This otherwise almost unnoticeable acquisition highlights the prevailing belief that innovative, natural products will provide growth in markets where traditional ones might not. In February 2018 another acquisition followed, this time one of a skincare company named Snowberry, which also specializes in natural ingredients. It is safe to say that the almost 200-year-old giant is entering a new period characterized by inorganic growth and less dependence on the classic brands such as Gillette and Tide. But two questions need yet to be unanswered. Why did P&G decide to target the consumer-health industry and why Merck’s business specifically? A short description of P&G’s recent results is needed to better understand the reasoning behind such decision.

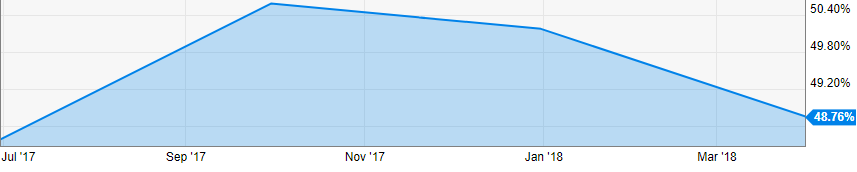

Procter & Gamble recently announced profits of $2.5 billion on $16.3 billion of sales during the third fiscal quarter ended March 30. This represents an increase in sales of 4% year over year. However, organic sales, a metric used to exclude acquisitions-based growth, saw an increase of only 1%, half of what had been seen in the first 6 months. Even more worrisome is the fact that the Cincinnati-based firm saw its gross margin decrease 1 percentage point to 48.8%, reflecting the loss in price power caused by increased competition.

Procter & Gamble has divested significantly over the decade, aiming to streamline its operations to the most profitable brands. In recent years, the company sold around 100 of its brands, while keeping only the remaining 65, split into 10 product categories. In 2015, a $12.5 billion transaction for the license to market a large portfolio of cosmetics brands including Gucci and Hugo Boss pulled P&G away from the Perfumes industry. In the following year P&G sold famous batteries manufacturer Duracell to Berkshire Hathaway, as Warren Buffet cleverly exchanged his P&G shares to avoid a major tax burden. However, the firm’s strategy has suffered a clear change recently, as management believes that increasing revenues through faster-growing products is crucial to sustain growth and competitiveness in the long term. Acquisitions can put the company on a fast track to reach this goal.

The relatively small acquisition in November 2017 of the San Francisco-based deodorant brand Native Deodorant for $100 million in cash serves as a clear example, given that P&G already owned the popular brand Secret operating in the same market. This otherwise almost unnoticeable acquisition highlights the prevailing belief that innovative, natural products will provide growth in markets where traditional ones might not. In February 2018 another acquisition followed, this time one of a skincare company named Snowberry, which also specializes in natural ingredients. It is safe to say that the almost 200-year-old giant is entering a new period characterized by inorganic growth and less dependence on the classic brands such as Gillette and Tide. But two questions need yet to be unanswered. Why did P&G decide to target the consumer-health industry and why Merck’s business specifically? A short description of P&G’s recent results is needed to better understand the reasoning behind such decision.

Procter & Gamble recently announced profits of $2.5 billion on $16.3 billion of sales during the third fiscal quarter ended March 30. This represents an increase in sales of 4% year over year. However, organic sales, a metric used to exclude acquisitions-based growth, saw an increase of only 1%, half of what had been seen in the first 6 months. Even more worrisome is the fact that the Cincinnati-based firm saw its gross margin decrease 1 percentage point to 48.8%, reflecting the loss in price power caused by increased competition.

The announcement of the acquisition came hours before these metrics were unveiled, so it is still unclear how the market is valuing the deal on its own. In early trading Thursday P&G shares plunged 4.6% to $74.65 and ended the week trading at $73.75, which can be consistent with the gross margin decrease on its own. As shareholders worry about the firm’s future, analysts flooded management with blunt questions regarding the turnaround strategy that the company has been through. "How long should investors be asked to wait?", Deutsche Bank analyst Steve Powers asked CEO David Taylor.

The acquisition comes in a crucial time to battle these issues. The German firm is a very strong player in the OTC market, which covers products that do not need prescription, and it appeals to P&G with its “steady, broad-based growth”, as Mr. Taylor argued. The acquisition will give Procter & Gamble control of vitamin manufacturers such as Seven Seas and Neurobion, which are faster-growing than the portfolio of products owned by the American giant. The bundle of products to be acquired has seen an average growth of 6% in the past 2 years, twice as high as the growth in traditional consumer goods. Most importantly, the margins in Merck’s products are higher than the average margin of P&G, which could offset the recent squeeze caused by intensifying competition from Walmart, Costco and Amazon. Mr Taylor said on Thursday that the company is operating in “several difficult markets” that are being “disrupted and transformed”. Management is now seeking inorganic alternatives to boost margins and growth in new areas. “I don’t think investors have to wait too long... we’re taking steps to change”, the executive added, possibly hinting that the deal is an integrating part of the general turnaround strategy of the company.

The acquisition comes in a crucial time to battle these issues. The German firm is a very strong player in the OTC market, which covers products that do not need prescription, and it appeals to P&G with its “steady, broad-based growth”, as Mr. Taylor argued. The acquisition will give Procter & Gamble control of vitamin manufacturers such as Seven Seas and Neurobion, which are faster-growing than the portfolio of products owned by the American giant. The bundle of products to be acquired has seen an average growth of 6% in the past 2 years, twice as high as the growth in traditional consumer goods. Most importantly, the margins in Merck’s products are higher than the average margin of P&G, which could offset the recent squeeze caused by intensifying competition from Walmart, Costco and Amazon. Mr Taylor said on Thursday that the company is operating in “several difficult markets” that are being “disrupted and transformed”. Management is now seeking inorganic alternatives to boost margins and growth in new areas. “I don’t think investors have to wait too long... we’re taking steps to change”, the executive added, possibly hinting that the deal is an integrating part of the general turnaround strategy of the company.

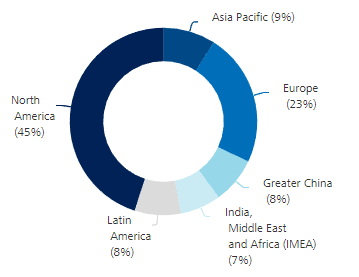

In fact, combining the existing business with Merck’s consumer-health division is completely in line with P&G’s strategy, at a very core level. Not only can the firm leverage its global reach to increase the sales of the 900 products to be acquired, but also benefit from Merck’s reach to gain greater exposure in Latin American and Asian markets and increase the growth of traditional brands through geographical expansion. P&G will increase its $7.5 billion health-care business by approximately $1 billion distributed among various OTC product categories. Moreover, the deal includes the acquisition of Indian consumer-health business Merck Ltd and a following tender offer to minority shareholders, which will strengthen P&G’s footprint in the IMEA region, which is underrepresented at 7% of net sales excluding Corporate.

Overall, the deal seems to be a clever maneuver of which investors shall not be afraid. The suspicion that P&G could be making acquisitions as a last resource to fight adversities is understandable given recent results. After careful analysis, we believe that the overnight announced deal is a well-crafted move in line with the company’s strategy, and for a reasonable price. The transaction implicitly values Merck’s business at 4.2 times its annual sales, which is a fair price in the industry according to past transactions. For drug manufacturers such as Merck, their consumers divisions are typically not as attractive as they are to consumer goods firms, since the margins are lower compared to the prescription pharmaceuticals business. For P&G as a leader in consumer goods however, the margins are very attractive and the business complementary on both geographic and product pipeline terms, making the division much more valuable to the acquirer than to the seller. It will be interesting to see how Procter & Gamble exploits this new value driver and whether new acquisitions may be announced in the near future, in a time when the turnaround may be close to an end.

João Coelho

Overall, the deal seems to be a clever maneuver of which investors shall not be afraid. The suspicion that P&G could be making acquisitions as a last resource to fight adversities is understandable given recent results. After careful analysis, we believe that the overnight announced deal is a well-crafted move in line with the company’s strategy, and for a reasonable price. The transaction implicitly values Merck’s business at 4.2 times its annual sales, which is a fair price in the industry according to past transactions. For drug manufacturers such as Merck, their consumers divisions are typically not as attractive as they are to consumer goods firms, since the margins are lower compared to the prescription pharmaceuticals business. For P&G as a leader in consumer goods however, the margins are very attractive and the business complementary on both geographic and product pipeline terms, making the division much more valuable to the acquirer than to the seller. It will be interesting to see how Procter & Gamble exploits this new value driver and whether new acquisitions may be announced in the near future, in a time when the turnaround may be close to an end.

João Coelho