India’s financial system is currently facing a big crisis. Lenders’ problems have become one of the most important issues for financial authorities, as they try to address a wave of bad loans that has already led to some non-bank lenders collapsing. In the beginning of the month, India’s central bank seized control of the heavily indebted Yes Bank, the fourth-largest private lender, replacing its board and temporarily limiting withdrawals to Rs50,000. The RBI previously found that Yes had under-reported its bad loans in its most recent financial year. In addition, a few days after RBI’s intervention, Mr Kapoor, Yes Bank’s co-founder was arrested by agents from the Enforcement Directorate, the government agency responsible for investigating financial crimes such as money-laundering and fraud.

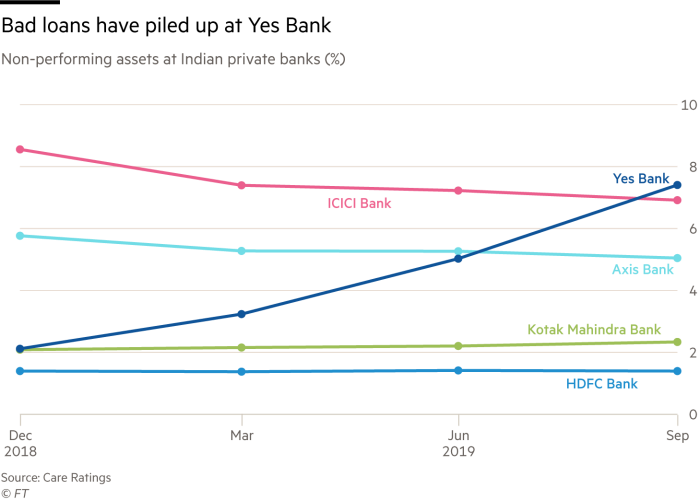

Recent credit downgrades of the Indian private bank had triggered the invocation of bond covenants by investors and withdrawal of deposits. In the last quarter the bank reported a net loss of Rs185.6bn ($2.5bn) in comparison to Rs10bn net profit a year earlier. It also showed a significant worsening in its loan book, with non-performing assets rising to 19% of loans compared to 2% of the previous year, which eroded Yes Bank’s capital base well below the regulatory minimum designed to prevent bank failures. The RBI disclosed a restructuring plan that involves the State Bank of India, India’s largest government-owned bank, investing up to $1.3bn for a 49% stake in Yes Bank, with leading private lenders such as HDFC, ICICI and Axis also taking part. Indian authorities have established a 30-day deadline to complete the rescue. About $4bn is needed to cover the hole in the Indian private bank’s balance sheet caused by loan losses.

Amongst all the private banks founded in the India’s boom years, Yes Bank was the most ambitious and aggressive. Founded in 2004, it had a reputation for having an appetite for risky bets, refused by more conservative private lenders, which eventually proved its major vulnerability, as India’s economy deteriorated. In 2019 the new management raised $270m from investors, but it was not enough to overcome the burden of past bad loans which had piled up in an increasingly slowing economy. Yes Bank was indeed confronting a liquidity crisis after it had tried for months to raise up to $2bn to shore up its fragile balance sheet, after being hit by its exposure to shadow lenders such as housing finance groups Indiabulls and Dewan, as well as Anil Ambani’s now-bankrupt Reliance Communications, but time run out: regulators had little choice than to take control of it.

Recent credit downgrades of the Indian private bank had triggered the invocation of bond covenants by investors and withdrawal of deposits. In the last quarter the bank reported a net loss of Rs185.6bn ($2.5bn) in comparison to Rs10bn net profit a year earlier. It also showed a significant worsening in its loan book, with non-performing assets rising to 19% of loans compared to 2% of the previous year, which eroded Yes Bank’s capital base well below the regulatory minimum designed to prevent bank failures. The RBI disclosed a restructuring plan that involves the State Bank of India, India’s largest government-owned bank, investing up to $1.3bn for a 49% stake in Yes Bank, with leading private lenders such as HDFC, ICICI and Axis also taking part. Indian authorities have established a 30-day deadline to complete the rescue. About $4bn is needed to cover the hole in the Indian private bank’s balance sheet caused by loan losses.

Amongst all the private banks founded in the India’s boom years, Yes Bank was the most ambitious and aggressive. Founded in 2004, it had a reputation for having an appetite for risky bets, refused by more conservative private lenders, which eventually proved its major vulnerability, as India’s economy deteriorated. In 2019 the new management raised $270m from investors, but it was not enough to overcome the burden of past bad loans which had piled up in an increasingly slowing economy. Yes Bank was indeed confronting a liquidity crisis after it had tried for months to raise up to $2bn to shore up its fragile balance sheet, after being hit by its exposure to shadow lenders such as housing finance groups Indiabulls and Dewan, as well as Anil Ambani’s now-bankrupt Reliance Communications, but time run out: regulators had little choice than to take control of it.

Yes Bank had previously granted large loans against collateral that was tough difficult to evaluate or size, such as “personal guarantees” which were practically inapplicable by the tycoons. In addition to interest rates, it also collected high one-time “fees for granting some loans, an income stream that gave it incentives to look more favourably on riskier borrowers that rivals may have spurned. One analyst said Mr Kapoor “was willing to accept borderline dodgy credits that most banks would not accept. The one-time fee would make his numbers look good in a particular year when the loan was made, but subjected it to a huge amount of risk down the line.”

A couple of weeks after its takeover, Yes Bank was permitted to resume normal operations after an infusion of Rs100bn ($1.4bn) in fresh capital by a consortium of eight public and private sector banks, led by government-owned State Bank of India. The attempted revival represents an important experiment for the Indian financial system, as the RBI has never attempted to preserve the independent brand identity of a failed bank and restore its operations. Analysts say that depositors’ confidence will depend on whether the rescue consortium can shore up the bank. Suman Chowdhury, president of Acuité Ratings and Research, says if depositors lost confidence in Yes Bank that could spread to other private banks, having serious repercussions on India’s already weakened financial sector.

Edoardo D'Aprile

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

Cover image by Paul Hamilton (flickr): https://www.flickr.com/photos/paulhami/14652981798/in/photostream/

A couple of weeks after its takeover, Yes Bank was permitted to resume normal operations after an infusion of Rs100bn ($1.4bn) in fresh capital by a consortium of eight public and private sector banks, led by government-owned State Bank of India. The attempted revival represents an important experiment for the Indian financial system, as the RBI has never attempted to preserve the independent brand identity of a failed bank and restore its operations. Analysts say that depositors’ confidence will depend on whether the rescue consortium can shore up the bank. Suman Chowdhury, president of Acuité Ratings and Research, says if depositors lost confidence in Yes Bank that could spread to other private banks, having serious repercussions on India’s already weakened financial sector.

Edoardo D'Aprile

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

Cover image by Paul Hamilton (flickr): https://www.flickr.com/photos/paulhami/14652981798/in/photostream/