Latin America is no safe place for investors who are not used to risk taking. In such markets, one would be well advised to, as the old saying goes, “sleep with one eye open”, so as not to get caught by the sudden changes in market sentiment, caused so frequently by political and economic outbursts.

Recently, we have seen many countries in the region struggling to keep volatility at bay, as is the case of Chile, where a number of protests against the government are taking the streets, and Argentina, where the left-wing party won elections and brought with it the fear of another default.

The main objective of this article is to explain these recent instabilities and show how they affected investors’ views on some of the region’s most important economies. In that sense, I shall analyze recent movements in Brazil’s, Chile’s and Argentina’s most liquid 10-year benchmark bonds, in an effort to capture the risk sentiment involving each of these countries.

Chile:

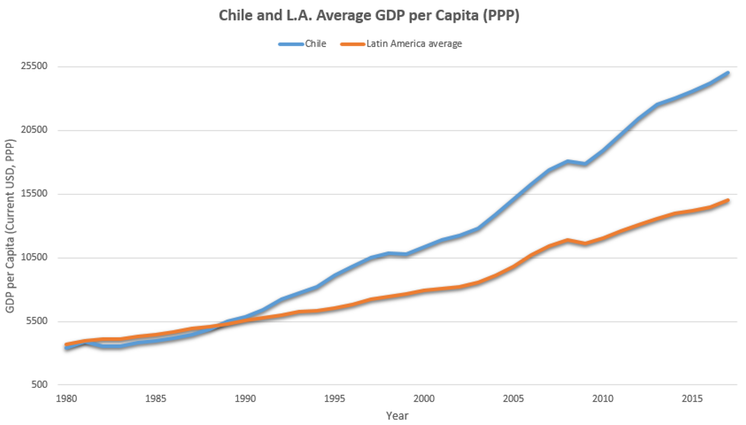

Chile has been, for the better part of the last two decades, the apple of investors’ eyes when it came to Latin America. With a solid record of fiscal responsibility and sound governance, Chile has been growing at a steady annual rate of around 4.5% in the last 20 years, with a public debt that has ranged from 5% to 30% of GDP – much lower than its peers in the region, such as Brazil, which has a public debt of almost 80% of total GDP. On top of that, Chile is considered a model for open economies, having established free trade agreements with a whole network of countries. Such a successful economic policy has led the country to be the highest rated country in the region, being rated as A1 by Moody’s and A+ by both Fitch and S&P.

Recently, we have seen many countries in the region struggling to keep volatility at bay, as is the case of Chile, where a number of protests against the government are taking the streets, and Argentina, where the left-wing party won elections and brought with it the fear of another default.

The main objective of this article is to explain these recent instabilities and show how they affected investors’ views on some of the region’s most important economies. In that sense, I shall analyze recent movements in Brazil’s, Chile’s and Argentina’s most liquid 10-year benchmark bonds, in an effort to capture the risk sentiment involving each of these countries.

Chile:

Chile has been, for the better part of the last two decades, the apple of investors’ eyes when it came to Latin America. With a solid record of fiscal responsibility and sound governance, Chile has been growing at a steady annual rate of around 4.5% in the last 20 years, with a public debt that has ranged from 5% to 30% of GDP – much lower than its peers in the region, such as Brazil, which has a public debt of almost 80% of total GDP. On top of that, Chile is considered a model for open economies, having established free trade agreements with a whole network of countries. Such a successful economic policy has led the country to be the highest rated country in the region, being rated as A1 by Moody’s and A+ by both Fitch and S&P.

Source: Trading Economics

Recently, however, Chile has been through what might be its most severe turbulence in the last couple of decades, due to popular protests that took over the streets on October the 21st, after the government increased Metro fares. Soon after the first protests took place, the government announced the suspension of the increase, but that was far from enough to stop the protesters. They quickly evolved into critics against social inequality in the country, which is one of the highest amongst developed countries, and the second highest in Latin America (second only Brazil’s). Protesters said they were struggling to make ends meet because of the high costs of partly-privatized education and health systems, rents and utilities, and a privatized pension system has been widely rejected by Chileans because of its low and often delayed payouts.

These protests evolved into strikes, which halted part of the country’s production, especially due to the involvement of copper miners (Chile exports 1/3 of the world’s copper, with such an export amounting to 15% of GDP as of 2018). With the involvement of miners in these protests, futures contracts on copper spiked from $2.65/Oz on October 21st to $2.77/Oz on November 7th, the highest price registered in the fourth quarter of 2019.

All of that put a heavy cloud over Chile’s future. Is there more volatility to come? Will the government be able to overcome popular pressure without giving up on its fiscal responsibility, or will it succumb to the temptation of resorting to an irresponsible approach, which could raise government debt to more worrisome levels? Will the government maintain a reasonable level of legitimacy to continue ruling?

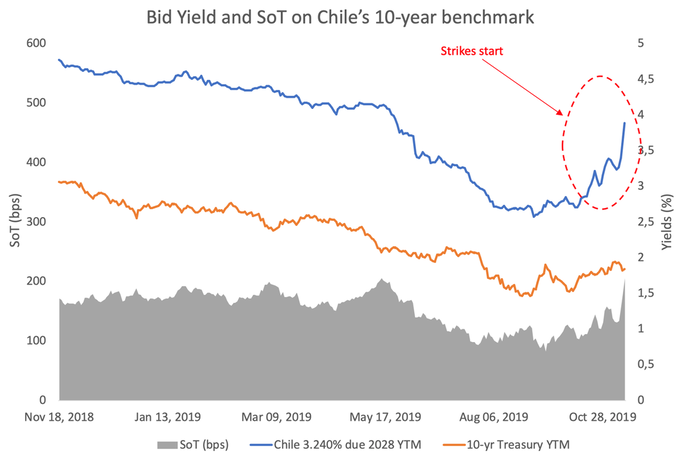

With such an uncertain future, investors started to price Chile in a riskier way, with the yields on its 10-year benchmark bond spiking from a low of 2.57% to 3.89%, a more than 130bps increase in less than a month. As a result of that move, the Chilean 10-year bond Spread over the Treasury benchmark went from 120bps to 210bps, its 1-year high, which shows investors' aversion to Chile’s risk at the moment. We can expect prices to remain volatile in the short-term, with investors staying on the sidelines until a clearer result has been reached. We can see in the chart below the recent spike in spreads after the beginning of the protests:

These protests evolved into strikes, which halted part of the country’s production, especially due to the involvement of copper miners (Chile exports 1/3 of the world’s copper, with such an export amounting to 15% of GDP as of 2018). With the involvement of miners in these protests, futures contracts on copper spiked from $2.65/Oz on October 21st to $2.77/Oz on November 7th, the highest price registered in the fourth quarter of 2019.

All of that put a heavy cloud over Chile’s future. Is there more volatility to come? Will the government be able to overcome popular pressure without giving up on its fiscal responsibility, or will it succumb to the temptation of resorting to an irresponsible approach, which could raise government debt to more worrisome levels? Will the government maintain a reasonable level of legitimacy to continue ruling?

With such an uncertain future, investors started to price Chile in a riskier way, with the yields on its 10-year benchmark bond spiking from a low of 2.57% to 3.89%, a more than 130bps increase in less than a month. As a result of that move, the Chilean 10-year bond Spread over the Treasury benchmark went from 120bps to 210bps, its 1-year high, which shows investors' aversion to Chile’s risk at the moment. We can expect prices to remain volatile in the short-term, with investors staying on the sidelines until a clearer result has been reached. We can see in the chart below the recent spike in spreads after the beginning of the protests:

In the chart, Spread Over Treasury (SoT) was calculated as yield on Chile’s 10-year benchmark minus yield on 10-year treasury, and plotted on the primary vertical axis. Both yields were plotted on the secondary vertical axis. Source: Investing.com.

Brazil:

Brazil’s story is much different from that of Chile. While the latter has had two decades of continuous growth, the former has suffered ups and downs, especially in the last 10 years. The country started this decade with a strong economic growth, with GDP increasing almost 8% in 2010. However, irresponsible fiscal and monetary policies left the country in a brutal recession in 2015-2016, with GDP contracting around 3.80% in both years and public debt soaring to almost 80% of GDP. From 2017 to nowadays, the country has managed to stop economic contraction and make some advancements towards a more solid economic growth.

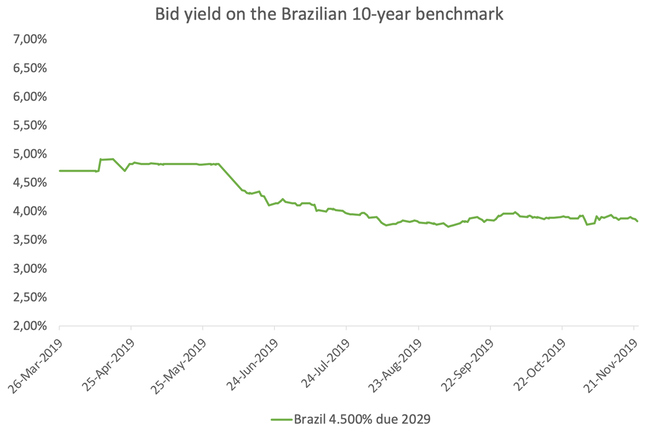

In 2019, the newly elected government, led by president Jair Bolsonaro, started to pursue a more liberal economic agenda, built upon three main pillars: structural reforms (the most illustrative example is the recently approved Social Security reform), openness of the economy (trade agreements between Mercosur and Europe) and reduction of the government’s size, specially by selling state-owned companies (this year the government has divested from many companies via secondary offerings on the form of follow-ons. This has been the case, for example, of BR Distribuidora). With this promising new economic policy, financial markets have started to put more faith in Brazil’s recovery, causing the 10-year benchmark to rally more than 90bps since its issuance in March of this year, taking yields from 4.7% to 3.8%.

In what relates to recent volatility in the region, Brazil managed to stay out of the recent confusions involving Chile and Bolivia (where protests are taking the streets after ex-president Evo Morales was overthrown by the opposition), which explains the lack of volatility in 10-year notes in the last month, with investors maintaining a positive outlook on Brazil, despite the region’s chaos. However, should protests start to take place in Brazilian streets, volatility is expected to pick-up.

Before we move on to the next country, it is interesting to compare Brazil’s yield to that of some of the region’s investment grade countries. By taking a look at Mexico (currently trading at 3.23%), Colombia (trading at 3.12%), Chile (trading at 3.89%) and Uruguay (trading at 3.14%), we see that Brazil trades inside Chile and closer to the others than the rating difference of at least three notches might suggest (currently Brazil is rated as BB- by S&P and the others are rated at least as BBB-). This might be a hint that markets are pricing an upgrade in Brazil’s sovereign credit rating in the medium or short term.

Brazil’s story is much different from that of Chile. While the latter has had two decades of continuous growth, the former has suffered ups and downs, especially in the last 10 years. The country started this decade with a strong economic growth, with GDP increasing almost 8% in 2010. However, irresponsible fiscal and monetary policies left the country in a brutal recession in 2015-2016, with GDP contracting around 3.80% in both years and public debt soaring to almost 80% of GDP. From 2017 to nowadays, the country has managed to stop economic contraction and make some advancements towards a more solid economic growth.

In 2019, the newly elected government, led by president Jair Bolsonaro, started to pursue a more liberal economic agenda, built upon three main pillars: structural reforms (the most illustrative example is the recently approved Social Security reform), openness of the economy (trade agreements between Mercosur and Europe) and reduction of the government’s size, specially by selling state-owned companies (this year the government has divested from many companies via secondary offerings on the form of follow-ons. This has been the case, for example, of BR Distribuidora). With this promising new economic policy, financial markets have started to put more faith in Brazil’s recovery, causing the 10-year benchmark to rally more than 90bps since its issuance in March of this year, taking yields from 4.7% to 3.8%.

In what relates to recent volatility in the region, Brazil managed to stay out of the recent confusions involving Chile and Bolivia (where protests are taking the streets after ex-president Evo Morales was overthrown by the opposition), which explains the lack of volatility in 10-year notes in the last month, with investors maintaining a positive outlook on Brazil, despite the region’s chaos. However, should protests start to take place in Brazilian streets, volatility is expected to pick-up.

Before we move on to the next country, it is interesting to compare Brazil’s yield to that of some of the region’s investment grade countries. By taking a look at Mexico (currently trading at 3.23%), Colombia (trading at 3.12%), Chile (trading at 3.89%) and Uruguay (trading at 3.14%), we see that Brazil trades inside Chile and closer to the others than the rating difference of at least three notches might suggest (currently Brazil is rated as BB- by S&P and the others are rated at least as BBB-). This might be a hint that markets are pricing an upgrade in Brazil’s sovereign credit rating in the medium or short term.

Source: Eikon

Argentina:

If investing in any emerging market requires a high tolerance for risk, investing in Argentina requires even more so. The country is currently fighting economic recession and rising unemployment and inflation, which is running at more than 55%. Concurrently, the country is fighting hard not to default on its external debt for the ninth time in its history.

To make things even worse in the eyes of financial markets, recently the pro-market and investor-friendly president Mauricio Macri suffered a crushing defeat to the left-wing candidate Alberto Fernandez, who vowed to renegotiate the massive IMF bailout package to end the “Social Catastrophe” it had imposed on Argentinian people. However, it isn’t Fernandez that is spooking investors, but the ever present figure of his vice president Cristina Kirchner, who was the president from 2007-2015, when Argentina defaulted twice on government debt. Cristina repeatedly refused to pay back sovereign debt, notably to US hedge funds, which she described as "vultures”.

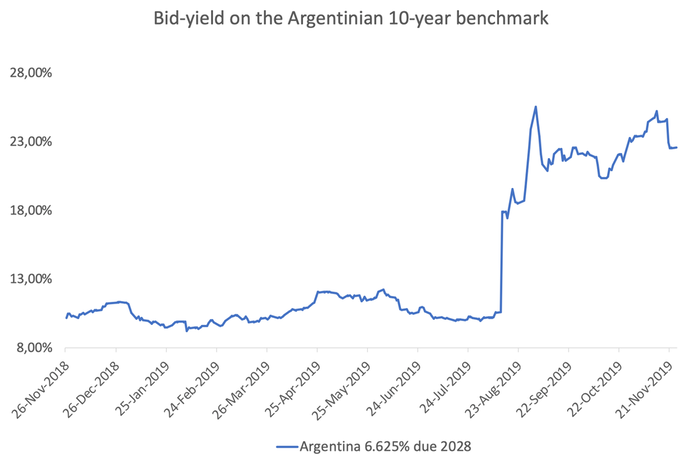

In light of these recent political events, the yields on the 10-year Argentinian Sovereign bonds spiked from 10.62% in August 12th to 17.88% in August 13th, a 7.26% increase right after the announcement of the primary election results. Since then, markets have continued to worsen their views on such credit, with current yields standing at 22.59%. More volatility is expected in the short term, with investors waiting to see what will be the next government’s approach to try and handle the difficult Argentinian economic situation.

If investing in any emerging market requires a high tolerance for risk, investing in Argentina requires even more so. The country is currently fighting economic recession and rising unemployment and inflation, which is running at more than 55%. Concurrently, the country is fighting hard not to default on its external debt for the ninth time in its history.

To make things even worse in the eyes of financial markets, recently the pro-market and investor-friendly president Mauricio Macri suffered a crushing defeat to the left-wing candidate Alberto Fernandez, who vowed to renegotiate the massive IMF bailout package to end the “Social Catastrophe” it had imposed on Argentinian people. However, it isn’t Fernandez that is spooking investors, but the ever present figure of his vice president Cristina Kirchner, who was the president from 2007-2015, when Argentina defaulted twice on government debt. Cristina repeatedly refused to pay back sovereign debt, notably to US hedge funds, which she described as "vultures”.

In light of these recent political events, the yields on the 10-year Argentinian Sovereign bonds spiked from 10.62% in August 12th to 17.88% in August 13th, a 7.26% increase right after the announcement of the primary election results. Since then, markets have continued to worsen their views on such credit, with current yields standing at 22.59%. More volatility is expected in the short term, with investors waiting to see what will be the next government’s approach to try and handle the difficult Argentinian economic situation.

Source: Eikon

Having discussed all three countries, we can see that the current situation in Latam is anything but certain. Investors should continue on the lookout in the next couple of months, most likely keeping volatility at high levels, scaring the risk-averse and promoting outflows of capital from the region.

João Paulo Parizotto – 28/12/2019