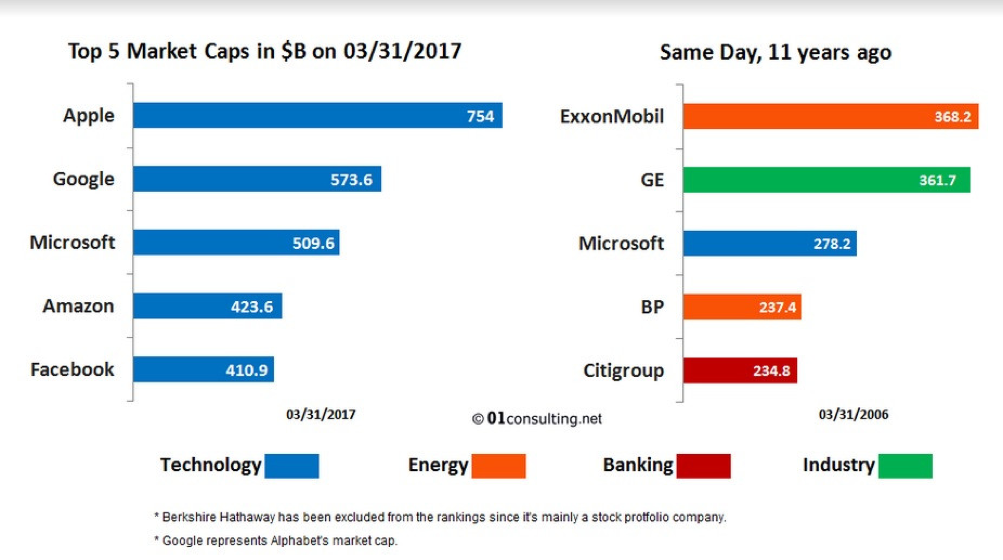

Regulation is becoming an increasing source of concern for the tech sector. Over the past 10 years, Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Alphabet (Google’s parent company) have grown to become, together with Microsoft, which successfully maintained its leading position, the world’s five largest companies by market capitalisation, thus starting to appear as monopolies. Google has about 42% of all American digital advertising and 80% of online search advertising. Up to now, the search giant has counted on benign regulators and political goodwill in the US. This seems to be changing.

Source: 01Consulting.net

Google isn’t new to trouble in Europe. In June, it has been sanctioned with a €2.4bn fine for anticompetitive behaviour: the European Commission found that it had manipulated the ranking of online-shopping results from rivals in its search results. Margrethe Vestager, the EU commissioner for competition, has announced further inquiries and fines if Google will fail to change its policies and to address the issue in a convincing manner. The media giant also faces a suit for illegally gathering the personal data of millions of iPhone users in the UK. Other investigations are ongoing in European countries. The European Commission considers lack of competition damaging to consumers, and is now more actively committed to persecuting tech multinationals over antitrust and tax compliance.

In the US, Google has always enjoyed a friendlier regulatory environment. The major investigation over its behaviours was closed in 2013 when the Federal and Trade Commission declared itself content with Google’s promise to change some of its practices. Nevertheless, regulatory concerns about the tech giant have recently been taken more seriously.

Last year, Washington’s and Utah’s attorney-generals asked the FTC to reopen its investigation. On November 13th, Missouri’s attorney general launched an investigation into the company over alleged violations of anti-trust and consumer protection laws. Other states are starting to scrutinise both Google’s anti-competitive behaviour and its policies for collecting consumer data.

American political and popular favour has also shifted against the firm: it is popular opinion that Google has done too little to limit Russian mediatic interference over the internet during the presidential election campaign. Furthermore, Google can no longer count on the privileged relationship with Washington it enjoyed during the Obama administration, when the chairman of Alphabet was an informal advisor to the president. In fact, the tech industry has not been equally supportive of the Republican candidate during the presidential campaign. The new officers selected by Trump are expected to take a more independent and activist approach. Joe Simon’s, Trump’s nominee to run the FTC, is rumoured to be an aggressive activist.

The Department of Justice has recently become more active on competition issues as well, having opposed the AT&T and Time Warner merger because of antitrust concerns. The Federal Communications Commission represents another source of uncertainty: On November 21st, it has announced that it will abolish the regulation on net-neutrality, the principle that internet service providers must not charge differently by user or content. This will harm YouTube, which is owned by Google, because internet providers may start charging more for access to video data.

It is hard to speculate whether these changes will eventually result in a generalised re-examination of antitrust law. Tech giants can claim that, since their services are free, no consumer harm is committed. However, one thing is sure: Google can no longer count on the same degree of popularity and political protection it relied upon in the past.

Pietro Menoni

In the US, Google has always enjoyed a friendlier regulatory environment. The major investigation over its behaviours was closed in 2013 when the Federal and Trade Commission declared itself content with Google’s promise to change some of its practices. Nevertheless, regulatory concerns about the tech giant have recently been taken more seriously.

Last year, Washington’s and Utah’s attorney-generals asked the FTC to reopen its investigation. On November 13th, Missouri’s attorney general launched an investigation into the company over alleged violations of anti-trust and consumer protection laws. Other states are starting to scrutinise both Google’s anti-competitive behaviour and its policies for collecting consumer data.

American political and popular favour has also shifted against the firm: it is popular opinion that Google has done too little to limit Russian mediatic interference over the internet during the presidential election campaign. Furthermore, Google can no longer count on the privileged relationship with Washington it enjoyed during the Obama administration, when the chairman of Alphabet was an informal advisor to the president. In fact, the tech industry has not been equally supportive of the Republican candidate during the presidential campaign. The new officers selected by Trump are expected to take a more independent and activist approach. Joe Simon’s, Trump’s nominee to run the FTC, is rumoured to be an aggressive activist.

The Department of Justice has recently become more active on competition issues as well, having opposed the AT&T and Time Warner merger because of antitrust concerns. The Federal Communications Commission represents another source of uncertainty: On November 21st, it has announced that it will abolish the regulation on net-neutrality, the principle that internet service providers must not charge differently by user or content. This will harm YouTube, which is owned by Google, because internet providers may start charging more for access to video data.

It is hard to speculate whether these changes will eventually result in a generalised re-examination of antitrust law. Tech giants can claim that, since their services are free, no consumer harm is committed. However, one thing is sure: Google can no longer count on the same degree of popularity and political protection it relied upon in the past.

Pietro Menoni