Inflation across the ocean

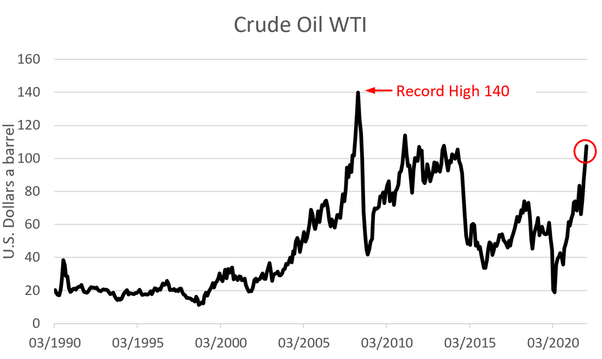

The debate surrounding inflation and whether it is simply transitory, or more permanent and deeply rooted, has taken on added importance in Latin America where a number of countries have had to reevaluate the implementation of their economic policies. While there are arguments for both, I believe that inflation in Latin America is at risk of becoming more entrenched as wage pressures translate into higher prices, which in turn risks creating a spiral that leads to further wage pressure. We have seen meaningful increases in energy and other commodities, real-estate, rents, wages and consumer goods. There are both cyclical and structural reasons behind the recent rise in commodity prices. Inflation tends to be a natural consequence of economic recovery and concomitant higher inflation expectations. In this particular environment, commodity prices rose on the wave of recovery and growth due to increased economic activity, consumption and aggregate demand. The structural overlay of the transitioning from fossil-fuel intensive economies to a carbon-neutral environment has added additional pressure on energy prices, writ large by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The debate surrounding inflation and whether it is simply transitory, or more permanent and deeply rooted, has taken on added importance in Latin America where a number of countries have had to reevaluate the implementation of their economic policies. While there are arguments for both, I believe that inflation in Latin America is at risk of becoming more entrenched as wage pressures translate into higher prices, which in turn risks creating a spiral that leads to further wage pressure. We have seen meaningful increases in energy and other commodities, real-estate, rents, wages and consumer goods. There are both cyclical and structural reasons behind the recent rise in commodity prices. Inflation tends to be a natural consequence of economic recovery and concomitant higher inflation expectations. In this particular environment, commodity prices rose on the wave of recovery and growth due to increased economic activity, consumption and aggregate demand. The structural overlay of the transitioning from fossil-fuel intensive economies to a carbon-neutral environment has added additional pressure on energy prices, writ large by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The recent surge in the demand for transition minerals has been fuelled by several factors. In particular, the tightened regulations on decarbonization and the related widespread sense of urgency, the increased requirement of electricity to power clean energy technologies such as electric vehicles, renewable sources of energy such as wind turbine farms, solar photovoltaic plants, battery storage, and other low carbon power generation that involve relatively more raw materials to construct. All of the above is driven by economies that are inevitably substituting their energy sources to become more sustainable. This translates into larger demand for four minerals that will become protagonists of the low carbon economy. Namely, copper, lithium, cobalt, and nickel, followed by graphite, manganese as well as other rare earth elements. Currently, analysts do not expect the supply of these essential minerals to cover future demand and avoid shortages in the future, as outlined by the International Energy Agency in the report “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions”, causing sustained high prices. Moreover, supply is constrained by lack of investments, protests against the mining business, a disorganized global pipeline, increasingly unmanageable sites due to geology issues as well as by their scarcity.

The metals behind the green revolution

The pandemic forced many countries to take extreme policy actions to combat the severe economic downturn. Both the US and Europe injected extraordinary amounts of liquidity into the system via fiscal and monetary policy, resulting in a quicker than expected economic rebound and now inflation. The economic recovery led to drastic increases in aggregate demand for goods as well as increased energy consumption, investments and a return to pre-pandemic behavior. The pandemic also forced many investors, companies and governments to reevaluate their stance on the energy transition, which is evident in the infrastructure development in the West. The focus on infrastructure development (particularly for EV) will require significant amounts of metals, which positions Latin America as a source of supply for that demand. According to The World Bank in fact, “over three billion tonnes of metal will be required by 2050 to deploy sufficient wind, solar and geothermal power, plus energy storage, to meet carbon targets”.

Some of the fundamental metals needed to support the energy transition are found in Latin America. Chile and Peru hold roughly two-fifths of the world’s production in copper, with Chile being the world’s largest. Chile also has over 20% of the world’s lithium supplies, and Brazil is an important producer of aluminum and iron ore. What makes Latin America attractive for sourcing these metals is that it's the lowest cost producer, has cheap labor and an established infrastructure with high-quality products. More importantly, growing tensions between the US and China will cause further divisions globally and because of its close proximity to the US and historic relations, Latin America should be the natural trading partner.

The pandemic forced many countries to take extreme policy actions to combat the severe economic downturn. Both the US and Europe injected extraordinary amounts of liquidity into the system via fiscal and monetary policy, resulting in a quicker than expected economic rebound and now inflation. The economic recovery led to drastic increases in aggregate demand for goods as well as increased energy consumption, investments and a return to pre-pandemic behavior. The pandemic also forced many investors, companies and governments to reevaluate their stance on the energy transition, which is evident in the infrastructure development in the West. The focus on infrastructure development (particularly for EV) will require significant amounts of metals, which positions Latin America as a source of supply for that demand. According to The World Bank in fact, “over three billion tonnes of metal will be required by 2050 to deploy sufficient wind, solar and geothermal power, plus energy storage, to meet carbon targets”.

Some of the fundamental metals needed to support the energy transition are found in Latin America. Chile and Peru hold roughly two-fifths of the world’s production in copper, with Chile being the world’s largest. Chile also has over 20% of the world’s lithium supplies, and Brazil is an important producer of aluminum and iron ore. What makes Latin America attractive for sourcing these metals is that it's the lowest cost producer, has cheap labor and an established infrastructure with high-quality products. More importantly, growing tensions between the US and China will cause further divisions globally and because of its close proximity to the US and historic relations, Latin America should be the natural trading partner.

We are seeing a trend where the West is looking for more independence from material and energy sources coming from countries like China and Russia. Recently, the US and Europe have coordinated in a search to replace its Russian oil supply and looked to Latin America. US Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm has made it clear that the US must focus on increasing its domestic oil supplies, causing discomfort among the current administration and their push for a reduction in oil and carbon energy sources. Despite ending diplomatic relations with Venezuela in 2019, Colombia criticized US diplomats for appearing to restart its relations with Venezuela and potentially importing crude oil from Venezuela. Historically, the region has capitalized on commodity price cycles responding with additional barrels of oil and supplies of metals. However, Latin American countries are ill-prepared to meet the new demand of western countries because they have not prepared to increase demand accordingly, and this could contribute further to inflation in the area. Brazil and Guyana have the most potential to expand their production but are not in a position like US Shale or onshore producers in the Middle East. It is unlikely that Latin America can reach full capacity and meet short-term demand from the US and elsewhere before 2023.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has highlighted the importance oil still holds in our global economy and the damaging effects it can have on prices and consumers. There is certainly an opportunity in many Latin American countries to increase production, but that may be in opposition to the current pressures to push for a more sustainable future. The US and Europe will likely need to expand production on their own and make a decision whether it is worth investing and accelerating oil production over the medium to long run. This is especially important when nuclear energy seems to have been ruled out as a viable source.

There was an unprecedented spike in nickel prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which indirectly led to a cash windfall for producers in Latin America. Russia was the world’s third largest nickel producer: itproduced 250,000 tons of the metal, which is a key component in stainless steel manufacturing. Brazil, however, is Latin America’s top producer and generated 100,000 tons in 2021 and is benefitting from many countries shifting their focus away from Russian production. There are several other drivers for the sharp increase in nickel prices which include stainless steel demand rising very sharply, investment demand due to energy transition and sustainable infrastructure as well as general price increases following the depressed demand during 2020. At present, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shows no signs of being resolved in the short term. As a result, elevated commodity prices, including nickel, will drive strong margins for Latin American producers and present a new alternative to Russia at a global level.

The M&A boom in commoddity market

It is in these peculiar market conditions that the Latam mining market is thriving, leading to a booming M&A period in the sector due to the expansion necessities of big traditional energy players as well as the urgency to switch to a low carbon economy. Indeed, in 2021 the Latam region M&A mining deals amounted to a total of around US$9bn according to BNamericas, in a context of rising prices for these raw materials. Indeed, Latin American countries are critical players in the sector, and they are currently reaping the benefits of increased trade volume caused by the disruptions that followed the Russian-Ukrainian crisis. With blocked supplies from these countries, the dependence on Latam for several raw materials along with other commodities such as oil surged in this period of booming prices. In an attempt to exploit this rising demand for transition minerals and to counterbalance the decreased request for traditional hydrocarbon resources, the Big Four Mining Companies are implementing projects to increase exposure in the transition minerals business, especially through acquisitions. Both to survive and to grow, all of the big miners are investing in activities related to electrification minerals in addition to having committed to achieving net-zero emissions.

The largest mining company in the region, BHP, invested among other projects in SolGold, a miner active in Ecuador focused on sustainable practices that invested itself in Alpala in 2020 and expects to start operations in 2025 through underground mines of copper. Another key global player in the industry, Rio Tinto, acquired a project from Rincon Mining related to lithium in Argentina for US$825mln to grow into the battery metals used for instance for electric vehicles, smartphones, and computers. Anglo American, another of the big four, invested heavily in the copper business in Peru, Chile, and in the nickel sector in Brazil. In addition, the fourth one, Glencore, has reached the largest exposure in transition minerals even though it remains highly involved in traditional thermal coal production. Other noteworthy deals include Capstone Copper, a company that will be the result of a merger valued at US$3.3bn between Capstone Mining and Mantos with the goal of combining copper operations in Chile, Mexico, and in the US to strengthen the position in the Americas and achieve higher growth. Furthermore, Orocobre and Galaxy Resources merged at US$3.06bn in 2021 to consolidate activities in Argentina, Canada and Australia to become one of the major lithium players.

It is in these peculiar market conditions that the Latam mining market is thriving, leading to a booming M&A period in the sector due to the expansion necessities of big traditional energy players as well as the urgency to switch to a low carbon economy. Indeed, in 2021 the Latam region M&A mining deals amounted to a total of around US$9bn according to BNamericas, in a context of rising prices for these raw materials. Indeed, Latin American countries are critical players in the sector, and they are currently reaping the benefits of increased trade volume caused by the disruptions that followed the Russian-Ukrainian crisis. With blocked supplies from these countries, the dependence on Latam for several raw materials along with other commodities such as oil surged in this period of booming prices. In an attempt to exploit this rising demand for transition minerals and to counterbalance the decreased request for traditional hydrocarbon resources, the Big Four Mining Companies are implementing projects to increase exposure in the transition minerals business, especially through acquisitions. Both to survive and to grow, all of the big miners are investing in activities related to electrification minerals in addition to having committed to achieving net-zero emissions.

The largest mining company in the region, BHP, invested among other projects in SolGold, a miner active in Ecuador focused on sustainable practices that invested itself in Alpala in 2020 and expects to start operations in 2025 through underground mines of copper. Another key global player in the industry, Rio Tinto, acquired a project from Rincon Mining related to lithium in Argentina for US$825mln to grow into the battery metals used for instance for electric vehicles, smartphones, and computers. Anglo American, another of the big four, invested heavily in the copper business in Peru, Chile, and in the nickel sector in Brazil. In addition, the fourth one, Glencore, has reached the largest exposure in transition minerals even though it remains highly involved in traditional thermal coal production. Other noteworthy deals include Capstone Copper, a company that will be the result of a merger valued at US$3.3bn between Capstone Mining and Mantos with the goal of combining copper operations in Chile, Mexico, and in the US to strengthen the position in the Americas and achieve higher growth. Furthermore, Orocobre and Galaxy Resources merged at US$3.06bn in 2021 to consolidate activities in Argentina, Canada and Australia to become one of the major lithium players.

The LatAm market for energy was positively affected for a number of reasons: high demand for certain minerals, the transition to a low economy at a time of restricted supply for essential materials, and the necessity to find alternative producers of oil and energy following the disruptions in Ukraine and Russia. Moreover, due to some fundamental characteristics of the local market, including the low costs of production, the high quality of the materials, a relatively good infrastructure and the current difficulties that other exporters are facing, the M&A market in the region prospered, with major energy producers seeking growth through acquisitions in the area. What remains unanswered is whether the current energy prices will remain at these high levels in a new supercycle that investors could exploit or whether they will eventually fall after a temporary spike.

Sources

by Miriam Franceschinelli and Nicolas Lockhart

Sources

- Financial Times

- Reuters

- Bloomberg

- The World Bank

- Factset

- IEA

- BNamericas

by Miriam Franceschinelli and Nicolas Lockhart