The deadline for the Saudi Aramco IPO, the most profitable company in the world, is approaching next month, and a deviation from the original international script is plausibly envisaged, re-adjusting notably the investors’ expectations based on the Saudi Vision 2030 reforms’ implementation, as well as creating room for new competitive scenarios in the oil industry revealing the OPEC revival’s weaknesses.

Saudi Vision 2030: Nitaqat as a thriving strategy for growth

The Saudi Crown Prince M.b. Salman proposed a National Transformation Plan aimed at diversifying the economy to reduce the reliance upon oil’s revenue, given the excessive volatility of the market, reversed on the national budget in the long run, increasing government revenues through levied fees extracted from working companies.

Technology advancement is encouraged with the privatization of state-owned entities and partnership in healthcare, to reduce unemployment rate of a growingly young and educated local labor force.

Saudi Vision 2030: Nitaqat as a thriving strategy for growth

The Saudi Crown Prince M.b. Salman proposed a National Transformation Plan aimed at diversifying the economy to reduce the reliance upon oil’s revenue, given the excessive volatility of the market, reversed on the national budget in the long run, increasing government revenues through levied fees extracted from working companies.

Technology advancement is encouraged with the privatization of state-owned entities and partnership in healthcare, to reduce unemployment rate of a growingly young and educated local labor force.

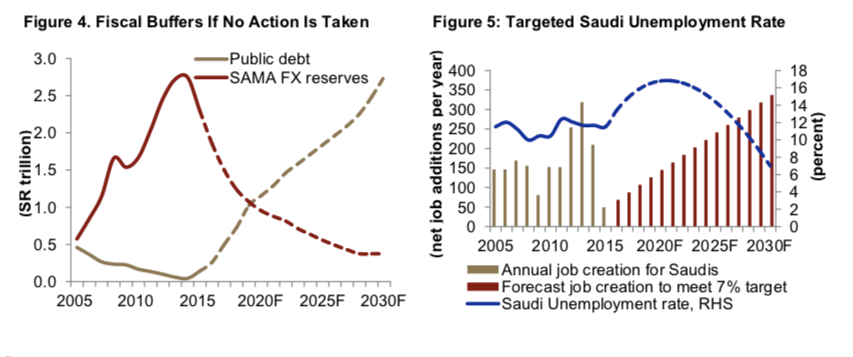

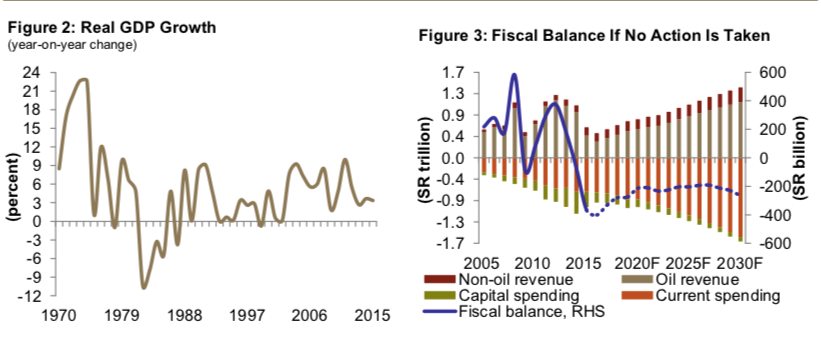

Source: Jadwa Investments, May 2019

Actions taken include: the creation of financial conglomerates, redirecting the transfer of vital facilities to integrate the Kingdom in a more global investor framework, and enhancing the productivity of the energy sector, affected indirectly by the shock wave in oil prices after the 2014 crisis.

Saudi Aramco IPO: a first step towards Saudization and Digitalization

The listing is a centerpiece milestone of the project: for the first time, shares previously held by the government funding are being offered to Saudi investors.

Aramco was foreign-owned since the government’s exploration concessions given to Standard Oil of California, back in the 1930s. The 1970s’ oil Embargo, Yom Kippur war and the 1981 OPEC creation, led to the outright appropriation from the government.

Despite defuelisation policies, the business will continue to prosper being cash generative, given the expected demand for hydrocarbons to hold steadily in the foreseeable future, and taking into account the ever-increasing cost of enhanced recovery of those products.

Attractive are investments in technology, yet applied in monitoring greenhouse gasses emissions and reducing time expenses, decisive in ensuring the profitability of the industry despite a 50 % fall in prices in 5 years, halved to 62 dollars per barrel.

Crucial is the company’s granted access and extended control over the world’s second largest crude oil reserve. Indeed, extraction costs are cheaper compared to Western majors, whose resources accessibility is politically constrained by environmental reputation and commercial unavailability of existing substitutes.

Additionally, bearing in mind the potential corruption and exclusive dealing presence in a state energy monopoly, managerial capability would likely to be strong. A supplementary evidence is given by the quick restored in operations after U.S. drones’ attacks suffered last September, which reduced temporarily the crude oil production by about 54%.

Actions taken include: the creation of financial conglomerates, redirecting the transfer of vital facilities to integrate the Kingdom in a more global investor framework, and enhancing the productivity of the energy sector, affected indirectly by the shock wave in oil prices after the 2014 crisis.

Saudi Aramco IPO: a first step towards Saudization and Digitalization

The listing is a centerpiece milestone of the project: for the first time, shares previously held by the government funding are being offered to Saudi investors.

Aramco was foreign-owned since the government’s exploration concessions given to Standard Oil of California, back in the 1930s. The 1970s’ oil Embargo, Yom Kippur war and the 1981 OPEC creation, led to the outright appropriation from the government.

Despite defuelisation policies, the business will continue to prosper being cash generative, given the expected demand for hydrocarbons to hold steadily in the foreseeable future, and taking into account the ever-increasing cost of enhanced recovery of those products.

Attractive are investments in technology, yet applied in monitoring greenhouse gasses emissions and reducing time expenses, decisive in ensuring the profitability of the industry despite a 50 % fall in prices in 5 years, halved to 62 dollars per barrel.

Crucial is the company’s granted access and extended control over the world’s second largest crude oil reserve. Indeed, extraction costs are cheaper compared to Western majors, whose resources accessibility is politically constrained by environmental reputation and commercial unavailability of existing substitutes.

Additionally, bearing in mind the potential corruption and exclusive dealing presence in a state energy monopoly, managerial capability would likely to be strong. A supplementary evidence is given by the quick restored in operations after U.S. drones’ attacks suffered last September, which reduced temporarily the crude oil production by about 54%.

Source: Jadwa Investments, May 2019

Exit from the global roadshow: Western sanctions, Gulf tensions and slowing growth rate

Sanctionary measures undertaken following on the US withdrawal from the nuclear deal in 2015, together with religious turmoil with Yemen and geopolitical risks arising from Saudi troops camped in Iran, are only partial reasons behind the reluctance of portfolio managers.

Unfamiliar with Saudi Arabia’s market, the latter received exposure to a global scope only after the inclusion of 32 securities in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index following the IPO announcement, currently accounting for the 2.4% of the stock, quite below the average of 11% for other developing countries.

Further uncertainty comes from international equity funds, given the global economic growth slowdown leading to a decline in energy prices, that could impact its overall economic health. Those factors amplified the damage to investors’ confidence by the lack of transparency, turned up by the government insulation from modern concerns, and the GDP-biasedness on state-owned land and oil reserve. Acquiring Aramco implies trusting the monarchy, in a scenario where crisis and risky tensions created a domino effect on investments, resulting in Saudi nationals’ purchasing power significantly diminished.

The wealth manager fear of lacking investors materialized: the original intention of selling 5% of the company’s shares, reduced to only 1.5%. Despite the undeliverable request of $ 2 trillion, multiple banks evaluated it at $1.7 trillion in order to raise $25 billion, shrinking the investors pool down to the Tadawul Saudi stock market.

Oil industry policy: OPEC its strategic relationships

The cash generated by the sale of equity will go to the PIF, the Saudi sovereign wealth fund, to invest in petroleum-unrelated sectors. Undoubtedly, to raise fiscal expenses, access to bigger capital markets would be needed, opening doors to outside investors. In a framework of oil-demand pie shrinks, the world’s lower cost-producer will want to secure and expand its market share concentration, pushing up capacity and leveraging access to maximize short-term profits, in line with stockholders’ interests.

The “Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries” enters the game, safeguarding revenues through price-supportive supply cuts. As the economist Philip Verlerger highlights, in order to show growth potential, Saudi Aramco will force non-OPEC companies to divert significant cash from drilling to share repurchases, pressuring their already slowly growing supply. Strategic are alliances with non-cartel supplier Russia and Asia, whose can guarantee, as “anchor” capitalists, high and stable valuation for Aramco, being keen on gaining political favor.

Can the economy be diversified anyway?

OPEC’s influence revived in recent decades, until the U.S shale oil boom in 2014 ranked them at the top, thanks to the fast recovery from low prices. Saudi Arabia served since then as a swing producer and buffer to oil price volatility.

However, in the need of selling more Aramco shares to execute the revitalization plan, the Kingdom will exert less influence over oil production, dragging also the other cartel member in a lower sphere of influence. Controversy kicks in the unbiased market price power will be yield to institutional figures, and U.S. producers, hurting even more capital spending capacity and profitability.

Furthermore, the oil group is set to become the largest company listed in the local stock exchange, at 77 % by composition, making doubtful the ability of shifting to a more balanced economy, less reliant on oil.

Centrality of politics: (un)willingness to modernize

Local advantage, potential growth and social intents spur the government to engage in innovation and restructuring of the industrial sector.

However, investment prowess seemed to vacillate when the political interference comes to light, and the interaction between a culturally constrained monarchy and institutional authorities can hardly unfold.

Revising the centrality of politics with new bargaining structures might be necessary conditions to hit the 2030 targets, otherwise intended to be only a blurred mirage.

Maria Vittoria Scino

Exit from the global roadshow: Western sanctions, Gulf tensions and slowing growth rate

Sanctionary measures undertaken following on the US withdrawal from the nuclear deal in 2015, together with religious turmoil with Yemen and geopolitical risks arising from Saudi troops camped in Iran, are only partial reasons behind the reluctance of portfolio managers.

Unfamiliar with Saudi Arabia’s market, the latter received exposure to a global scope only after the inclusion of 32 securities in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index following the IPO announcement, currently accounting for the 2.4% of the stock, quite below the average of 11% for other developing countries.

Further uncertainty comes from international equity funds, given the global economic growth slowdown leading to a decline in energy prices, that could impact its overall economic health. Those factors amplified the damage to investors’ confidence by the lack of transparency, turned up by the government insulation from modern concerns, and the GDP-biasedness on state-owned land and oil reserve. Acquiring Aramco implies trusting the monarchy, in a scenario where crisis and risky tensions created a domino effect on investments, resulting in Saudi nationals’ purchasing power significantly diminished.

The wealth manager fear of lacking investors materialized: the original intention of selling 5% of the company’s shares, reduced to only 1.5%. Despite the undeliverable request of $ 2 trillion, multiple banks evaluated it at $1.7 trillion in order to raise $25 billion, shrinking the investors pool down to the Tadawul Saudi stock market.

Oil industry policy: OPEC its strategic relationships

The cash generated by the sale of equity will go to the PIF, the Saudi sovereign wealth fund, to invest in petroleum-unrelated sectors. Undoubtedly, to raise fiscal expenses, access to bigger capital markets would be needed, opening doors to outside investors. In a framework of oil-demand pie shrinks, the world’s lower cost-producer will want to secure and expand its market share concentration, pushing up capacity and leveraging access to maximize short-term profits, in line with stockholders’ interests.

The “Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries” enters the game, safeguarding revenues through price-supportive supply cuts. As the economist Philip Verlerger highlights, in order to show growth potential, Saudi Aramco will force non-OPEC companies to divert significant cash from drilling to share repurchases, pressuring their already slowly growing supply. Strategic are alliances with non-cartel supplier Russia and Asia, whose can guarantee, as “anchor” capitalists, high and stable valuation for Aramco, being keen on gaining political favor.

Can the economy be diversified anyway?

OPEC’s influence revived in recent decades, until the U.S shale oil boom in 2014 ranked them at the top, thanks to the fast recovery from low prices. Saudi Arabia served since then as a swing producer and buffer to oil price volatility.

However, in the need of selling more Aramco shares to execute the revitalization plan, the Kingdom will exert less influence over oil production, dragging also the other cartel member in a lower sphere of influence. Controversy kicks in the unbiased market price power will be yield to institutional figures, and U.S. producers, hurting even more capital spending capacity and profitability.

Furthermore, the oil group is set to become the largest company listed in the local stock exchange, at 77 % by composition, making doubtful the ability of shifting to a more balanced economy, less reliant on oil.

Centrality of politics: (un)willingness to modernize

Local advantage, potential growth and social intents spur the government to engage in innovation and restructuring of the industrial sector.

However, investment prowess seemed to vacillate when the political interference comes to light, and the interaction between a culturally constrained monarchy and institutional authorities can hardly unfold.

Revising the centrality of politics with new bargaining structures might be necessary conditions to hit the 2030 targets, otherwise intended to be only a blurred mirage.

Maria Vittoria Scino