In the 80’s nobody would have believed the possibility of reducing interest rates as much as they are in today’s world economy. However, the general recession, the necessity of reducing the cost of loans to businesses and to households as to generate growth, made it happen. So, 4 years ago, the Bank of Japan’s governor Haruhiko Kuroda launched a program of quantitative and qualitative easing (QQE) since the conventional monetary policies resulted not to be enough to raise the economic performances. From April 2013, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) has put on the market approximately ¥ 700 billion (€5,7 billion) per year. Through these policies, the government of Japan aims to achieve three important goals:

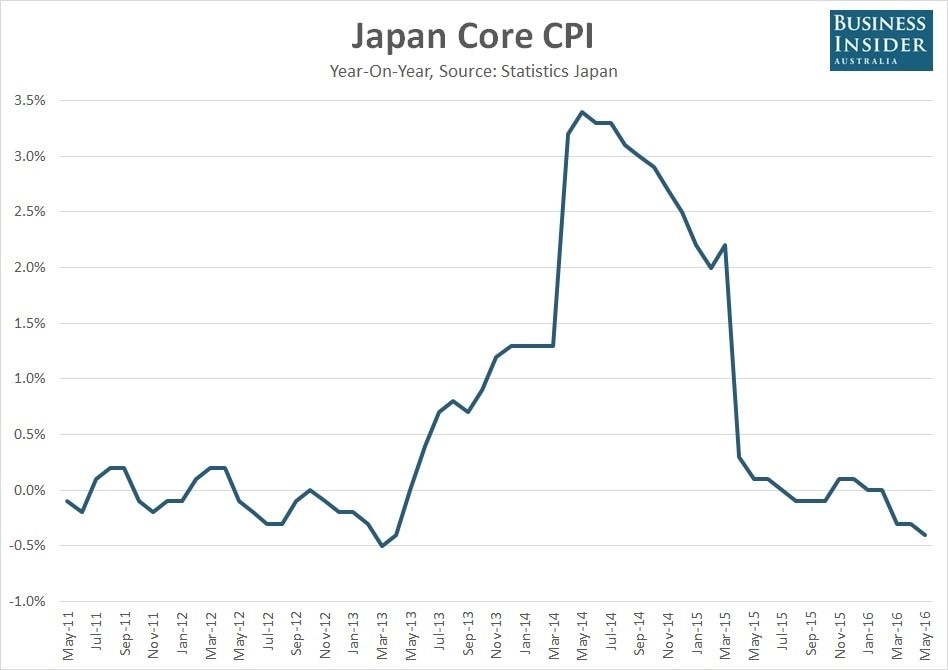

- a 2% inflation target that still seems very far to reach if we consider that last year the country was still in deflation;

- a 3% nominal growth;

- a primary budget surplus;

Thorough time these monetary policies have led to an extreme condition clearly understandable by referring to the IS-LM model. The increase of money supply has pushed down the LM curve so much that any other increase on money supply would have no effect on the interest rates: of course, a liquidity trap.

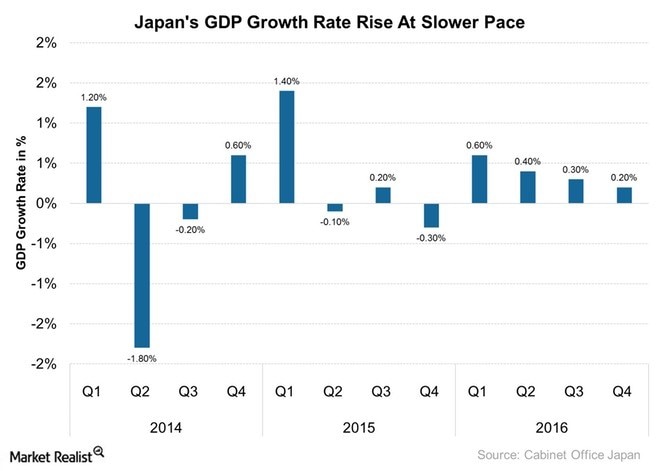

Despite that, Japan’s economy did not react as predicted and hoped by Shinzo Abe: investments still do not increase and inflation target of 2 % still seems to be difficultly achievable. The first graphic below clearly shows the variations of Japan inflation rates (Core CPI) over time while the second compares the GDP growth (annual %) of Japan in the last three years: Japan GDP is very little influenced by BoJ’ monetary policies.

Despite that, Japan’s economy did not react as predicted and hoped by Shinzo Abe: investments still do not increase and inflation target of 2 % still seems to be difficultly achievable. The first graphic below clearly shows the variations of Japan inflation rates (Core CPI) over time while the second compares the GDP growth (annual %) of Japan in the last three years: Japan GDP is very little influenced by BoJ’ monetary policies.

So, what are some of the reasons behind the insensitivity of Japanese economy to monetary policies?

- According to Haruhiko Kuroda, monetary policies are ineffective because of a consolidated mental belief of deflation in Japanese mentality. The habit of seeing a decrease in prices and wages over time has made Japanese disbelief of a possible future inflation and so they still avoid buying today hoping that “tomorrow it will be cheaper”.

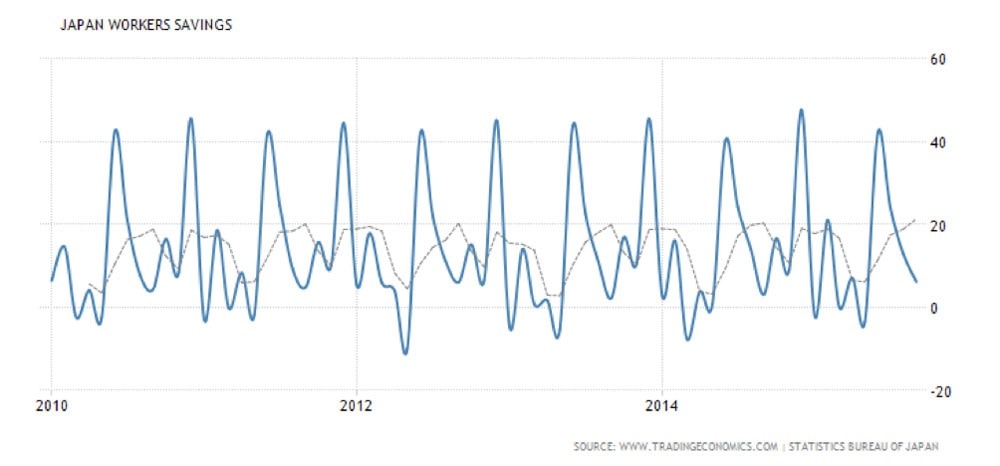

- Another main factor has probably to be found in the way Japanese administrate their wealth. There are people that earn $ 40,000 a year but put aside into bank accounts approximately 20% of it because they fear a depression and the fact that they will not have enough money when they retire. Moreover, this high propensity to save of the private sector is not compensate by other components of the national demand: neither the balance export-import nor the budget deficit are appropriate to mitigate the negative impact that the high propensity to save has on GDP. The graphic below shows the cyclic variations of workers’ savings (%).

A potential solution would consist in structural reforms aimed at strengthening and making more competitive Japanese exporters. However, the price to pay to achieve that goal would be a further reduction of salaries and worse working condition while, in reality, the main reasons of weak Japanese exports are foreign factors, such as the contraction in demand of the main export recipient (China).

Of course this article exemplifies things a lot and can’t be taken as the final word but it provides valid reasons of how the most important monetary experiment has failed and probably why a lot of new debates about the actual effectiveness of quantitative and qualitative easing have started. Alternative solutions to the current expansionary monetary policies are being explored but this would probably be a good topic for another article.

Nicola Bulgarelli

- Finally, a substantial percentage of the population simply does not spend because of low wages and beliefs that the situation will worsen in the future. According to a survey emitted by the BoJ, only 5% of the respondents have declared their intention to spend more next year, the remaining 95% will continue to reduce its expenses.

Of course this article exemplifies things a lot and can’t be taken as the final word but it provides valid reasons of how the most important monetary experiment has failed and probably why a lot of new debates about the actual effectiveness of quantitative and qualitative easing have started. Alternative solutions to the current expansionary monetary policies are being explored but this would probably be a good topic for another article.

Nicola Bulgarelli