High rates and their effects

Since the end of the 2008 financial crisis the world has seen a decade-long period of low interest rates, something which recently rapidly changed. It has been a year since the US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell announced the first rate hike in the current tightening cycle designed to fight inflation. For many years, banks held a significant portfolio of long-term bonds that over the past year have lost in market value due to higher interest rates. This made it even more important for banks to effectively hedge such portfolios against potential risks in high interest rate environments.

These types of environments have the capacity to create asset-liability duration mismatches that can become the fatal reason a bank is not able to meet customers’ demands for deposit withdrawals due to insufficient short-term liquidity. Anyone that bought bonds with longer durations has lost money on a market-to-market basis by sitting on large amounts of large unrealized losses. Holding longer duration assets is not a problem as long as banks have the equity and deposit base to hold the securities until maturity. Yet, these banks are at greater risk from rapid withdrawals given that they would need to realize losses to provide cash to depositors.

When this happens, the bank is forced to sell those longer duration securities and realize the loss. This spreads bad news, leading to uncertainty and ultimately to potential bank runs as depositors rush to withdraw their cash. What happened to Silicon Valley Bank might only be one of the first signals of a large market volatility as the Fed continues to implement tight monetary policies.

Silicon Valley Bank

Silicon Valley Bank was the 16th largest commercial bank in America when it first opened its doors in 1983. Nearly half of all US venture-backed technology and life science companies utilized SVB's banking services. Additionally, it operated in Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Sweden, Canada, China, Denmark, and the United Kingdom.

Due to extremely low borrowing costs and a surge in demand for digital services brought on by the pandemic, SVB greatly benefited from the tech sector's explosive growth in recent years. The bank's resources, which incorporate credits, dramatically multiplied from $71 billion toward the finish of 2019 to a pinnacle of $220 billion toward the finish of Walk 2022, as indicated by fiscal summaries. Over the course of that time, as thousands of tech startups parked their cash at the lender, deposits soared from $62 billion to $198 billion. Thanks to this rapid expansion, the bank doubled its workforce in a relatively short time.

Structure of SVB and losses

SVB's collapse on March 10th came suddenly, following a frenetic 48 hours during which customers yanked deposits from the lender in a classic bank run.

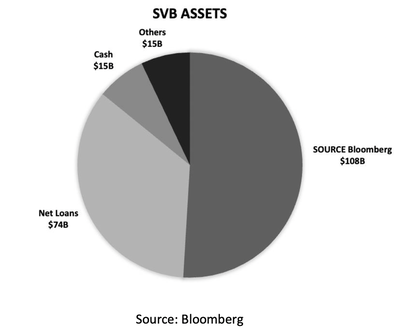

But the root of its demise goes back several years. Like many other banks, SVB ploughed billions into US government bonds during the era of near-zero interest rates. In 2021, during the funding boom, SVB amassed large deposits — $189 billion, which later peaked at a massive $198 billion. It later invested heavily in bonds, which were being issued in a low interest rate scenario. SVB’s balance sheet for the end of 2022 showed $91.3 billion of securities. The startup-focused bank had $209 billion in total assets and about $175.4 billion in total deposits, as of December 2022.

What seemed like a safe bet quickly came unstuck, as the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates aggressively to tame inflation. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall, so the jump in rates eroded the value of SVB's bond portfolio. The portfolio was yielding an average 1.79% return last week, far below the 10-year Treasury yield of around 3.9%. At the same time, the Fed's constant rate raise sent borrowing costs higher, meaning tech startups had to channel more cash towards repaying debt. Clients of SVB were also struggling to raise new venture capital funding and eventually companies were forced to draw down on deposits held by SVB to fund their operations and growth.

Since the end of the 2008 financial crisis the world has seen a decade-long period of low interest rates, something which recently rapidly changed. It has been a year since the US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell announced the first rate hike in the current tightening cycle designed to fight inflation. For many years, banks held a significant portfolio of long-term bonds that over the past year have lost in market value due to higher interest rates. This made it even more important for banks to effectively hedge such portfolios against potential risks in high interest rate environments.

These types of environments have the capacity to create asset-liability duration mismatches that can become the fatal reason a bank is not able to meet customers’ demands for deposit withdrawals due to insufficient short-term liquidity. Anyone that bought bonds with longer durations has lost money on a market-to-market basis by sitting on large amounts of large unrealized losses. Holding longer duration assets is not a problem as long as banks have the equity and deposit base to hold the securities until maturity. Yet, these banks are at greater risk from rapid withdrawals given that they would need to realize losses to provide cash to depositors.

When this happens, the bank is forced to sell those longer duration securities and realize the loss. This spreads bad news, leading to uncertainty and ultimately to potential bank runs as depositors rush to withdraw their cash. What happened to Silicon Valley Bank might only be one of the first signals of a large market volatility as the Fed continues to implement tight monetary policies.

Silicon Valley Bank

Silicon Valley Bank was the 16th largest commercial bank in America when it first opened its doors in 1983. Nearly half of all US venture-backed technology and life science companies utilized SVB's banking services. Additionally, it operated in Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Sweden, Canada, China, Denmark, and the United Kingdom.

Due to extremely low borrowing costs and a surge in demand for digital services brought on by the pandemic, SVB greatly benefited from the tech sector's explosive growth in recent years. The bank's resources, which incorporate credits, dramatically multiplied from $71 billion toward the finish of 2019 to a pinnacle of $220 billion toward the finish of Walk 2022, as indicated by fiscal summaries. Over the course of that time, as thousands of tech startups parked their cash at the lender, deposits soared from $62 billion to $198 billion. Thanks to this rapid expansion, the bank doubled its workforce in a relatively short time.

Structure of SVB and losses

SVB's collapse on March 10th came suddenly, following a frenetic 48 hours during which customers yanked deposits from the lender in a classic bank run.

But the root of its demise goes back several years. Like many other banks, SVB ploughed billions into US government bonds during the era of near-zero interest rates. In 2021, during the funding boom, SVB amassed large deposits — $189 billion, which later peaked at a massive $198 billion. It later invested heavily in bonds, which were being issued in a low interest rate scenario. SVB’s balance sheet for the end of 2022 showed $91.3 billion of securities. The startup-focused bank had $209 billion in total assets and about $175.4 billion in total deposits, as of December 2022.

What seemed like a safe bet quickly came unstuck, as the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates aggressively to tame inflation. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall, so the jump in rates eroded the value of SVB's bond portfolio. The portfolio was yielding an average 1.79% return last week, far below the 10-year Treasury yield of around 3.9%. At the same time, the Fed's constant rate raise sent borrowing costs higher, meaning tech startups had to channel more cash towards repaying debt. Clients of SVB were also struggling to raise new venture capital funding and eventually companies were forced to draw down on deposits held by SVB to fund their operations and growth.

SVB bank run

While SVB's problems can be traced back to its earlier investment decisions, the run on the bank was triggered on March 8th when the lender announced that it had sold $21 billion worth of securities from its portfolio at a loss and would sell $2.25 billion in new shares to plug the hole in its finances.

That set off panic among customers, who withdrew their money in large numbers.

The bank's stock plummeted 60% by March 9th and dragged other bank shares down with it as investors began to fear a repeat of the global financial crisis a decade and a half ago.

By March 10th, trading in SVB shares was halted and it had abandoned efforts to raise capital or find a buyer. California regulators intervened, shutting the bank down and placing it in receivership under the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which would most likely result in the liquidation of the bank's assets to pay back depositors and creditors.

Similarities of Silvergate and SVB

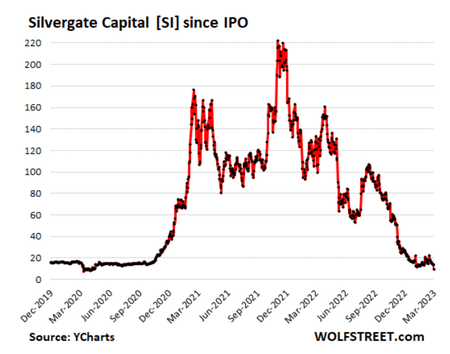

Explaining what happened to Silvergate is fundamental to understanding the situation with SVB and its underlying causes. Silvergate is a much smaller reality than SVB. The former had $6.3 billion in deposits at the end of 2022, a small fraction compared to SVB. Apart from this substantial difference in scale, we can draw many similarities in these two stories.

Silvergate started as a small real estate lender based in San Diego, but it slowly transformed into a “crypto-friendly” bank. It went public in 2019 and it became the interchange point between dollar and cryptocurrencies. It was in fact the only U.S. bank that was willing to take the risk of dealing with the shady and poorly regulated practices typical of the crypto industry. This fact gave them significant bargaining power and they were able to pay no interest on the deposits of these clients. Silvergate had a product called SEN leverage direct lending, where they would lend people money collateralized with bitcoin, which is not a very conservative nor safe way of using those deposits.

While SVB's problems can be traced back to its earlier investment decisions, the run on the bank was triggered on March 8th when the lender announced that it had sold $21 billion worth of securities from its portfolio at a loss and would sell $2.25 billion in new shares to plug the hole in its finances.

That set off panic among customers, who withdrew their money in large numbers.

The bank's stock plummeted 60% by March 9th and dragged other bank shares down with it as investors began to fear a repeat of the global financial crisis a decade and a half ago.

By March 10th, trading in SVB shares was halted and it had abandoned efforts to raise capital or find a buyer. California regulators intervened, shutting the bank down and placing it in receivership under the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which would most likely result in the liquidation of the bank's assets to pay back depositors and creditors.

Similarities of Silvergate and SVB

Explaining what happened to Silvergate is fundamental to understanding the situation with SVB and its underlying causes. Silvergate is a much smaller reality than SVB. The former had $6.3 billion in deposits at the end of 2022, a small fraction compared to SVB. Apart from this substantial difference in scale, we can draw many similarities in these two stories.

Silvergate started as a small real estate lender based in San Diego, but it slowly transformed into a “crypto-friendly” bank. It went public in 2019 and it became the interchange point between dollar and cryptocurrencies. It was in fact the only U.S. bank that was willing to take the risk of dealing with the shady and poorly regulated practices typical of the crypto industry. This fact gave them significant bargaining power and they were able to pay no interest on the deposits of these clients. Silvergate had a product called SEN leverage direct lending, where they would lend people money collateralized with bitcoin, which is not a very conservative nor safe way of using those deposits.

In the same way that they thrived with the crypto boom, they suffered with its collapse of the last year. They were exposed to a significant amount of risks tied to the way they did business. Clients started to withdraw their deposits and in order to fulfill these requests Silvergate had to sell some assets. This is where the story connects with SVB. Both companies experienced a bank run and were forced to sell Treasury Bonds. Selling this type of assets during a period of high interest is catastrophic for the balance sheet of a bank and it quickly erodes the bank capital. Again, they sold these bonds at a lower price having to suffer a significant loss. This would not have been a problem if they were being held until maturity, but Silvergate and SVB could not do so because they had to fulfil all the withdrawal requests. The important aspect to underline in this situation is that, although the causes of these two bank runs are different, at a high level the context is the same. The nature of their clientele, which is made of tech- oriented businesses and not households, exposes them to the same industry and interest rate risks. Nonetheless, given the fact that neither of them operates at a national level, their collapse is not necessarily a signal of a weak financial system. It might simply be, as some analysts called it, an “idiosyncratic situation”.

What this crisis led to

In the United States, the banking system as a whole has $22.9 trillion in assets and $20.7 trillion in liabilities. Assets are riskier and less liquid than their liabilities resulting in significant liquidity and solvency risks that must be managed carefully. In particular, commercial banks currently have just $3 trillion in cash to back up their $17.6 trillion in deposits. The majority of this cash is just a ledger entry with the U.S. Federal Reserve, and so it is not tangible. Somewhere around $100 billion of it ($0.1 trillion) is held by banks in the form of actual physical banknotes in vaults and ATMs.

In the United States the FDIC provides insurance against deposit losses up to $250,000 which mitigates some of the risk. This insurance proved to play a fundamental role in the sudden decrease of bank runs that happened right after its implementation until today. However, at any given time, FDIC only has about 1% of bank deposits’ worth of insurance in their fund. They can protect depositors against individual bank failures, but they don’t have enough to prevent system-wide banking failures, unless they draw in aid from elsewhere or are backstopped by Congress with a fiscal bailout.

Although we are still far from facing a systematic collapse of the banking system, it is clear that there are some weaknesses. Banks today are subject to significant duration risk on their longer-term assets (HTM) and, if left unhedged (which they are), it can lead to unrealized losses which can become realized if depositors request their funds immediately. The impact would not just be felt among VCs but the lending and credit markets as well. Banks, especially regional banks that tend to offer leverage against illiquid assets, will need to become more conservative and stringent with their offerings assuming the Fed continues to maintain a high level of rates.

Implication for banks

It is clear that the collapse of SVB has greatly benefited larger banks such as J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank of America as customers are looking to deposit their capital in institutions that are less likely to fail. This is the opposite of what the Fed would like, as it further concentrates the US financial systems and means that these banks are becoming increasingly more systemically important for the United States.

Moreover, as we can see from recent transactions, in the short term, it is likely that many banks will look to reevaluate their exposure and become more conservative with lending and tightening the credit market.

Conclusion

To conclude, this high interest rate environment the world is currently experiencing generates a lot of uncertainty in the banking industry and what happened to Silvergate and SVB is a clear example of this phenomena. Both banks faced bank runs due to a variety of factors which in the end led to their collapse; representing one of the biggest shocks for the banking industry since the 2008 financial crisis which led to many people fearing the worst. As of now, the main question is whether we will see something similar to other regional banks or even larger banks? Ultimately, after all these shaking events, will there be major changes in the banking industry in the coming months and years?

What this crisis led to

In the United States, the banking system as a whole has $22.9 trillion in assets and $20.7 trillion in liabilities. Assets are riskier and less liquid than their liabilities resulting in significant liquidity and solvency risks that must be managed carefully. In particular, commercial banks currently have just $3 trillion in cash to back up their $17.6 trillion in deposits. The majority of this cash is just a ledger entry with the U.S. Federal Reserve, and so it is not tangible. Somewhere around $100 billion of it ($0.1 trillion) is held by banks in the form of actual physical banknotes in vaults and ATMs.

In the United States the FDIC provides insurance against deposit losses up to $250,000 which mitigates some of the risk. This insurance proved to play a fundamental role in the sudden decrease of bank runs that happened right after its implementation until today. However, at any given time, FDIC only has about 1% of bank deposits’ worth of insurance in their fund. They can protect depositors against individual bank failures, but they don’t have enough to prevent system-wide banking failures, unless they draw in aid from elsewhere or are backstopped by Congress with a fiscal bailout.

Although we are still far from facing a systematic collapse of the banking system, it is clear that there are some weaknesses. Banks today are subject to significant duration risk on their longer-term assets (HTM) and, if left unhedged (which they are), it can lead to unrealized losses which can become realized if depositors request their funds immediately. The impact would not just be felt among VCs but the lending and credit markets as well. Banks, especially regional banks that tend to offer leverage against illiquid assets, will need to become more conservative and stringent with their offerings assuming the Fed continues to maintain a high level of rates.

Implication for banks

It is clear that the collapse of SVB has greatly benefited larger banks such as J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank of America as customers are looking to deposit their capital in institutions that are less likely to fail. This is the opposite of what the Fed would like, as it further concentrates the US financial systems and means that these banks are becoming increasingly more systemically important for the United States.

Moreover, as we can see from recent transactions, in the short term, it is likely that many banks will look to reevaluate their exposure and become more conservative with lending and tightening the credit market.

Conclusion

To conclude, this high interest rate environment the world is currently experiencing generates a lot of uncertainty in the banking industry and what happened to Silvergate and SVB is a clear example of this phenomena. Both banks faced bank runs due to a variety of factors which in the end led to their collapse; representing one of the biggest shocks for the banking industry since the 2008 financial crisis which led to many people fearing the worst. As of now, the main question is whether we will see something similar to other regional banks or even larger banks? Ultimately, after all these shaking events, will there be major changes in the banking industry in the coming months and years?

By Enrico Dametto, Severinas Freigofas, Federica Guirguis and Nicolas Lockhart

Sources

Bloomber

Politico

Financial Times

Atlantic Council

NY Times

Bloomber

Politico

Financial Times

Atlantic Council

NY Times