At the end they came back.

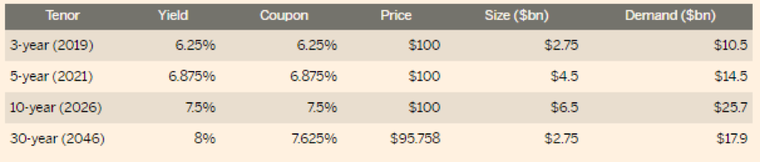

Argentina issued $16.5bn in 3, 5, 10 and 30 years denominated bonds, increased from the planned emission of $15bn, among exceptional interest on the markets with the demand peaked $70bn. This is the largest debt issue from an emerging market country in more than 20 years. Most of this fresh cash obtained by Argentina, around $9.3bn, has been destined to pay its remaining holdout creditors (among which there are many little bondholders such as 50.000 Italian citizens) ending the odyssey began with the 2001 $100bn default that left Argentina out of debt markets for 15 years.

Argentina issued $16.5bn in 3, 5, 10 and 30 years denominated bonds, increased from the planned emission of $15bn, among exceptional interest on the markets with the demand peaked $70bn. This is the largest debt issue from an emerging market country in more than 20 years. Most of this fresh cash obtained by Argentina, around $9.3bn, has been destined to pay its remaining holdout creditors (among which there are many little bondholders such as 50.000 Italian citizens) ending the odyssey began with the 2001 $100bn default that left Argentina out of debt markets for 15 years.

The high demand, driven by Mr. Macri policy of market friendly economic reforms, allowed Argentina to reduce the yield of bonds under analysts’ expectations with 10-years bonds yielding 7.5%,50 basis points under the expected yield of 8%, and the 30-years bonds yielding 8%, down from 8.85% expectations. But if this emission could be seen as a success for Argentina remember that a 7.5% yield in a strong currency as USD are very high, especially in a contest of interest rates near to zero, and this yield reflects that Argentina is still view with suspicion by investors; to make a comparison Colombia issued similar USD denominated bonds with a yield of 4%.

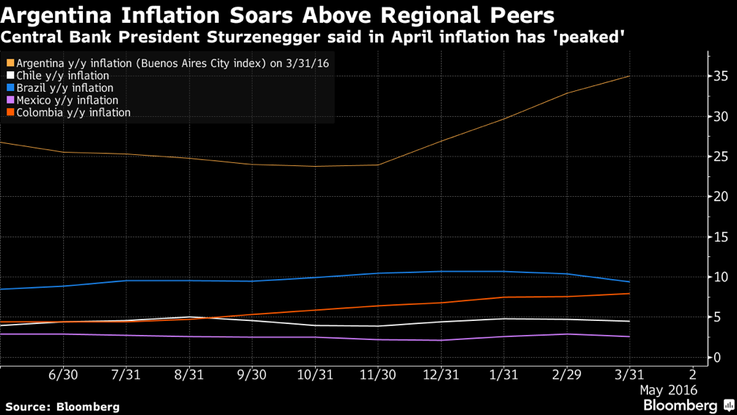

A separate consideration has to be made about the currency of the emission that is USD. At the moment Argentina is facing a period of high inflation and Peso is depreciating very fast also because of Macri’s policy of free movement of capital that realigned the official rate to the most realist black-market rate. The Latin American country is unable to attract interest in Peso-denominated bonds due to inflation issues (reported to be around 6% in April only but government’s statistics are not trusted by the majority of investors) and weak expectations about its economy that is expected to enter a period of recession next year.

One reason of the high demand is due to investors’ desperate search for yield in a period of near-to-zero interest rates and the absence of similar emissions in recent times that reduces diversification in high-yield bond portfolios. Also a possible return of Argentina’s ex-status of emerging markets could boost interest in its debt and capital markets.

Moody’s upgraded Argentina credit rating, still remaining firmly in junk territory, to B3 from Caa1 as default issues has been fixed and Mr. Macri’s policies are starting to improve public deficit; Moody’s is expecting economic growth and a decrease of inflation from the next year. Also Standard and Poor’s Global Ratings lifted Argentina’s rating to B- (as low as Greece’s), with stable outlook, after the payment of the past-due interest of defaulted bonds.

Mr. Macri’s austerity policies are starting to bite as fast as his popularity is decreasing, while remaining extremely high, especially in the provinces hit more by the cuts. Inflation and the correction (increased 6 times) of utilities tariffs remained frozen from years by the previous socialist government are also contributing to higher poverty rate in the country peaking 32% this year. Domestic export is focused on commodities such as soybeans that has been highly depreciated during past years (soybeans had recently rebound due to floods which hit the country) contributing to devaluate Peso.

Investors put a big bet on Argentina and Argentina put a big bet on itself, the common hope is that this bet will not be losing.

Tomaso Giorgi