Back to 2000’s Argentina was in the middle of a thunderstorm; an extremely severe crisis, imported from Brazil and Russia, along with widespread unemployment (peaked over 20%) and poverty hit Argentina’s economy so heavily that the period 1998-2002 is called Argentine Great Depression.

In 2001 Argentina declared default on 82 billion USD of sovereign debt, the second largest sovereign default after Greece haircut in 2012, and started in 2005 a restructuring plan that exchanged old bonds with new ones at a 25-35% of the nominal value and with longer terms. About 93% of Argentina’s bondholders accepted the restructuring plan, on the other hand the other 7% recently won the right to be repaid in full. From 2001 Argentina is completely sidelined from international debt markets, but maybe the time of this debt “apartheid” is over.

The new President Mauricio Macri started an important season of structural reforms trying to start an economic breakthrough and regain attention and enthusiasm of markets. UBS wealth management analysts commented Macri’s plan: “The change in direction of policymaking has been radical, it has been a 180 degree turn. Structural reform in emerging markets is scarce and you are getting a whole lot of it in Argentina.”

Macri’s market friendly policies peaked last week when Deutsche Bank announced that the Latin American country launched a five-days marketing tour, so called non-deal roadshow, through US and UK to sound the market sentiment. Investors have been told the offer could top 15 billion USD in 5,10 and 30 year USD denominated bonds, this would make Argentina the largest issuer of strong currency denominated bonds since the 20 billion USD emission of Mexico more than 20 years ago.

The biggest concerns are yields, Argentina is a high-risk issuer and yields that investors will claim will be appropriate to the risk. One European investment house said that it would invest only if the yield offered will be over 10%; making a comparison Bonar 2024 yields 7.9% fresh from a rally after the election of President Macri. A probable yield could be around 7.5%

Investors are pointing out that Argentina declared default on foreign debt 8 times since independence in 1816 and this for sur will not be a big perk for the country. There are still big concerns about Argentine economy, Government deficit is around 7% and inflation topped 32% in 2015. The issue of USD-denominated bonds will finance the deficit without lower Central Bank dollar reserves and to repay creditors (especially hedge funds) of its defaulted notes who won the lawsuit against the country. However, if Argentina issues too much hard currency bonds it risks to expose itself too much and the risk of the umpteenth financial instability spiral will be around the corner.

In 2001 Argentina declared default on 82 billion USD of sovereign debt, the second largest sovereign default after Greece haircut in 2012, and started in 2005 a restructuring plan that exchanged old bonds with new ones at a 25-35% of the nominal value and with longer terms. About 93% of Argentina’s bondholders accepted the restructuring plan, on the other hand the other 7% recently won the right to be repaid in full. From 2001 Argentina is completely sidelined from international debt markets, but maybe the time of this debt “apartheid” is over.

The new President Mauricio Macri started an important season of structural reforms trying to start an economic breakthrough and regain attention and enthusiasm of markets. UBS wealth management analysts commented Macri’s plan: “The change in direction of policymaking has been radical, it has been a 180 degree turn. Structural reform in emerging markets is scarce and you are getting a whole lot of it in Argentina.”

Macri’s market friendly policies peaked last week when Deutsche Bank announced that the Latin American country launched a five-days marketing tour, so called non-deal roadshow, through US and UK to sound the market sentiment. Investors have been told the offer could top 15 billion USD in 5,10 and 30 year USD denominated bonds, this would make Argentina the largest issuer of strong currency denominated bonds since the 20 billion USD emission of Mexico more than 20 years ago.

The biggest concerns are yields, Argentina is a high-risk issuer and yields that investors will claim will be appropriate to the risk. One European investment house said that it would invest only if the yield offered will be over 10%; making a comparison Bonar 2024 yields 7.9% fresh from a rally after the election of President Macri. A probable yield could be around 7.5%

Investors are pointing out that Argentina declared default on foreign debt 8 times since independence in 1816 and this for sur will not be a big perk for the country. There are still big concerns about Argentine economy, Government deficit is around 7% and inflation topped 32% in 2015. The issue of USD-denominated bonds will finance the deficit without lower Central Bank dollar reserves and to repay creditors (especially hedge funds) of its defaulted notes who won the lawsuit against the country. However, if Argentina issues too much hard currency bonds it risks to expose itself too much and the risk of the umpteenth financial instability spiral will be around the corner.

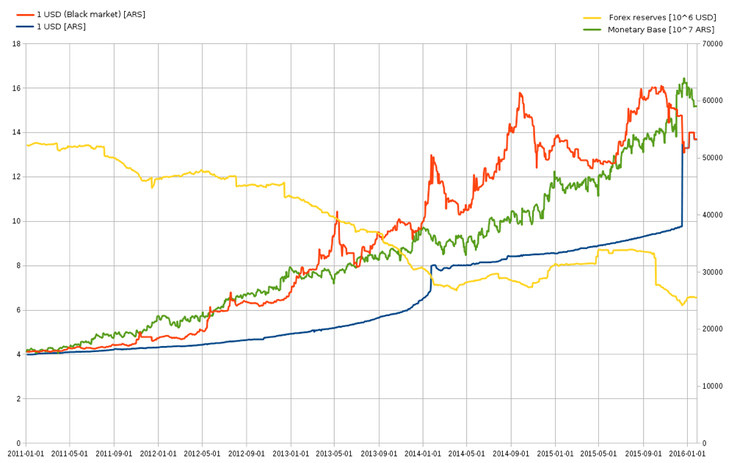

As far as I am concerned I think Argentina is still far from a complete economic recovery and maybe a 15 billion USD is a premature move that could be risky for country and for investors, maybe expectation in Macri’s policies is too high and boosted by decades of bad policies taken form past governments. Inflation is also a big issue for Latin America and Argentine Peso lost half of its value since December 2015 after Macri’s decision to lift capital controls to allow practically unlimited access to foreign currency and allowing the peso to freely float on the market (Peso lost 30% of its value the day of the announce realigning to the black market rate). As long as all these problems are not resolved I suggest an investment in Bonars only to professional speculative operators and not for who wants to allocate the savings of a life because too many times families, in Italy in particular, lost all their money in the black hole of Argentina’s bonds.

Tomaso Giorgi