A history of public subsidization

Korea’s rapid economic growth since the early 1960s “has been a government-directed development in which the principal engine has been private enterprise” (Mason, et al.. 1980). After taking control of the entire state through a coup, General Park appointed Lee Byung Chull, the country’s richest man, as chairman of the Promotional Committee for Economic Reconstruction. In this way, the military government began its partnership with the country’s entrepreneurial elite. The first step towards economic growth was the decision to nationalize all commercial banks and reorganize the banking system to have control over credit. Thanks to the latter, the state was able to give credit to specific companies to develop targeted industries. Moreover, these companies that were becoming increasingly influential received exemptions from import duties on capital goods. On the other hand, firms that were operating in industries not favored by the development plans found it extremely difficult both to gain access to credit and receive special discounts and exemptions. The most important feature of the alliance between big business and the state was the performance principle. As a matter of fact, the state was regularly monitoring companies in order to control if their support was used in an efficient manner. On the contrary, when they were not performing well, they lost state support. Hence, instead of political connections, performance was the only criteria to get access for preferential loans and other forms of state support. In addition, the government didn’t allow any company in any industry to achieve a monopoly but rather supported many different corporations in each industry in order to keep them efficient.

The case

As paradoxical as it may seem, the straw which broke the camel’s back in South Korea’s liquidity situation was a Legoland theme park. The deal between the Gangwon province and Merlin Entertainment Group, a company specialized in the construction of theme parks and owner of the rights to Legoland, was signed in mid 2011, and the park itself was opened and inaugurated on May 5, 2022. At the time, the governor of the Gangwon province was Choi Moon-soon, a liberal leader known for his strong propensity towards public spending. In order to finance the theme park, the Gangwon Jungdo Development Corporation (GJC) was established, which was owned 44% by the province and 22.5% by the Merlin Group. The objective of the GJC was to issue corporate bonds, which would have allowed for the construction of the theme park and would have covered most of the costs related to it. BNK Securities, a subsidiary of the Busan Bank, was chosen to serve as underwriter for the bond issuance. Choi Moon-soon agreed to this, stating that the Gangwon province would have served as a guarantee for the bond payments, alongside the land and property owned by the GJC. Considering the solid collateral of the bonds, and the backing from the South Korean provincial government, the securities obtained an A1 rating from Moody’s, signifying that they were to be considered “upper medium grade”. Unfortunately, due to the inconsistent and insufficient profits generated by the theme park once it had begun operating, the GJC was not able to repay its obligation in time, and therefore started contracting with BNK Securities to delay bond payments, obviously including a premium due to the temporal difference incurred. The latter negotiations were to all intents and purposes taking place, until on September 26th, 2022, the sudden announcement of Kim Jin-tae, Gangwon’s recently appointed governor, compromised the entire deal. The province leader stated that he disagreed with the liberal concessions his predecessor had made, and that the government would immediately cease its guarantee for the securities issued by the GJC. The reason behind this, according to Jin-tae, was that he was trying to reduce the debt which the former provincial government had created, financing an excessive number of projects with public funds. This resulted in BNK Securities defaulting on the GJC bonds and requesting that the Gangwon province return the entirety of the sum lost, approximately 200 billion won. The government vaguely announced that they would step in, but no amounts were stated, and neither was a specific date mentioned. The initial A1 rating of the GJC bonds turned to junk overnight, and the guarantee which the Gangwon province had given to other projects became practically worthless, creating a wave of uncertainty and concern in the whole South Korean market. As a result, interest rates skyrocketed, and corporations found themselves in an extremely tight liquidity situation. There had already been ongoing concerns regarding scarce liquidity in South Korea, but this event has brought them over the tipping point. As with any other shocking news, investors are always the first to react. For example, Korean Electric Power Corporations (KEPCO), one of the largest renewable energy distributors in the country, suffered a significant loss in their stock price after Kim Jin-tae’s announcement. The company was supposed to raise 1.2 billion won from debt but was only able to fulfill less than half of its requirements, due to investor’s rising concern regarding bond payments. This is portrayed in KEPCO’s share price, which dropped an astounding 18% from September 28th to October 26th. Other than this example, the Real Estate project market was definitely the sector which was influenced the most by the sudden change in investor confidence, also considering that government guarantees are very prominent within this industry. Dongbu Corporation, an important player in South Korean Real Estate, has been facing a continuous decrease in share price since September. On the other hand, indices such as the KOSPI and the FTSE Korea have not shown significant losses, but this is because they are mainly composed of large companies which have been performing well recently and have not suffered significantly from the liquidity crunch.

The Bond market reaction

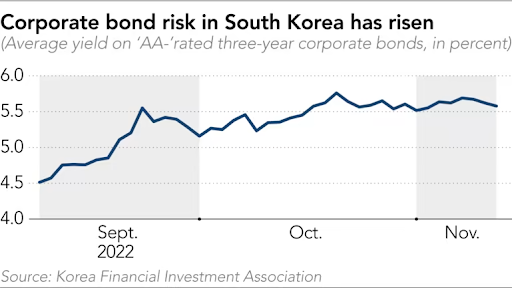

Liquidity crunches are never a good thing. Especially if they happen in a period of general economic uncertainty and globally rising interest rates. If it all started with just a missing bond payment of Won205bn ($150mn) bond payment in September by the developer of the Legoland Korea theme park outside Seoul, this has represented a shock to the entire bond market, starting a turmoil that has dragged down the perceived safety resulting in a spike of yields also for the top rated corporate bonds, rising more than 100 basis points in the last two months.

Korea’s rapid economic growth since the early 1960s “has been a government-directed development in which the principal engine has been private enterprise” (Mason, et al.. 1980). After taking control of the entire state through a coup, General Park appointed Lee Byung Chull, the country’s richest man, as chairman of the Promotional Committee for Economic Reconstruction. In this way, the military government began its partnership with the country’s entrepreneurial elite. The first step towards economic growth was the decision to nationalize all commercial banks and reorganize the banking system to have control over credit. Thanks to the latter, the state was able to give credit to specific companies to develop targeted industries. Moreover, these companies that were becoming increasingly influential received exemptions from import duties on capital goods. On the other hand, firms that were operating in industries not favored by the development plans found it extremely difficult both to gain access to credit and receive special discounts and exemptions. The most important feature of the alliance between big business and the state was the performance principle. As a matter of fact, the state was regularly monitoring companies in order to control if their support was used in an efficient manner. On the contrary, when they were not performing well, they lost state support. Hence, instead of political connections, performance was the only criteria to get access for preferential loans and other forms of state support. In addition, the government didn’t allow any company in any industry to achieve a monopoly but rather supported many different corporations in each industry in order to keep them efficient.

The case

As paradoxical as it may seem, the straw which broke the camel’s back in South Korea’s liquidity situation was a Legoland theme park. The deal between the Gangwon province and Merlin Entertainment Group, a company specialized in the construction of theme parks and owner of the rights to Legoland, was signed in mid 2011, and the park itself was opened and inaugurated on May 5, 2022. At the time, the governor of the Gangwon province was Choi Moon-soon, a liberal leader known for his strong propensity towards public spending. In order to finance the theme park, the Gangwon Jungdo Development Corporation (GJC) was established, which was owned 44% by the province and 22.5% by the Merlin Group. The objective of the GJC was to issue corporate bonds, which would have allowed for the construction of the theme park and would have covered most of the costs related to it. BNK Securities, a subsidiary of the Busan Bank, was chosen to serve as underwriter for the bond issuance. Choi Moon-soon agreed to this, stating that the Gangwon province would have served as a guarantee for the bond payments, alongside the land and property owned by the GJC. Considering the solid collateral of the bonds, and the backing from the South Korean provincial government, the securities obtained an A1 rating from Moody’s, signifying that they were to be considered “upper medium grade”. Unfortunately, due to the inconsistent and insufficient profits generated by the theme park once it had begun operating, the GJC was not able to repay its obligation in time, and therefore started contracting with BNK Securities to delay bond payments, obviously including a premium due to the temporal difference incurred. The latter negotiations were to all intents and purposes taking place, until on September 26th, 2022, the sudden announcement of Kim Jin-tae, Gangwon’s recently appointed governor, compromised the entire deal. The province leader stated that he disagreed with the liberal concessions his predecessor had made, and that the government would immediately cease its guarantee for the securities issued by the GJC. The reason behind this, according to Jin-tae, was that he was trying to reduce the debt which the former provincial government had created, financing an excessive number of projects with public funds. This resulted in BNK Securities defaulting on the GJC bonds and requesting that the Gangwon province return the entirety of the sum lost, approximately 200 billion won. The government vaguely announced that they would step in, but no amounts were stated, and neither was a specific date mentioned. The initial A1 rating of the GJC bonds turned to junk overnight, and the guarantee which the Gangwon province had given to other projects became practically worthless, creating a wave of uncertainty and concern in the whole South Korean market. As a result, interest rates skyrocketed, and corporations found themselves in an extremely tight liquidity situation. There had already been ongoing concerns regarding scarce liquidity in South Korea, but this event has brought them over the tipping point. As with any other shocking news, investors are always the first to react. For example, Korean Electric Power Corporations (KEPCO), one of the largest renewable energy distributors in the country, suffered a significant loss in their stock price after Kim Jin-tae’s announcement. The company was supposed to raise 1.2 billion won from debt but was only able to fulfill less than half of its requirements, due to investor’s rising concern regarding bond payments. This is portrayed in KEPCO’s share price, which dropped an astounding 18% from September 28th to October 26th. Other than this example, the Real Estate project market was definitely the sector which was influenced the most by the sudden change in investor confidence, also considering that government guarantees are very prominent within this industry. Dongbu Corporation, an important player in South Korean Real Estate, has been facing a continuous decrease in share price since September. On the other hand, indices such as the KOSPI and the FTSE Korea have not shown significant losses, but this is because they are mainly composed of large companies which have been performing well recently and have not suffered significantly from the liquidity crunch.

The Bond market reaction

Liquidity crunches are never a good thing. Especially if they happen in a period of general economic uncertainty and globally rising interest rates. If it all started with just a missing bond payment of Won205bn ($150mn) bond payment in September by the developer of the Legoland Korea theme park outside Seoul, this has represented a shock to the entire bond market, starting a turmoil that has dragged down the perceived safety resulting in a spike of yields also for the top rated corporate bonds, rising more than 100 basis points in the last two months.

This should be better understood in the wider framework of the current economic panorama.

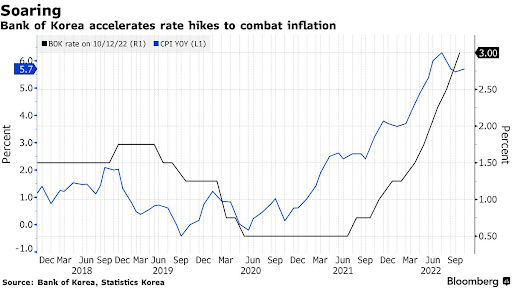

Let’s start with growth: not an exception to a seemingly global pattern, also South Korea is likely to experience a growth slowdown in the upcoming months, as a product of the increased energy prices and the restrictive monetary policies being implemented to fight inflation. Bank of Korea has indeed so far hiked interest rates of 275 basis points, and analysts observe how BoK is unlikely to pivot from its tightening as they are still committing to curb inflation as of now. The current monetary policy trends and inflation outlooks are visible in the chart aside, that represents indeed the policy rates together with the CPI index in the last few years. Last but not least, the global macro environment is also recently dominated by a very strong dollar. The dollar’s strength against the won adversely affects the trade balance, which is one of the pillars of Korea’s economy, and boosts import prices, thereby adding fuel to the skyrocketing domestic inflation: this is an opinion expressed by the Korea Capital Market Institute, that also remarks how a wave of corporate defaults is likely to lie ahead due to the aggravated liquidity and the unusually high credit spreads.

Let’s start with growth: not an exception to a seemingly global pattern, also South Korea is likely to experience a growth slowdown in the upcoming months, as a product of the increased energy prices and the restrictive monetary policies being implemented to fight inflation. Bank of Korea has indeed so far hiked interest rates of 275 basis points, and analysts observe how BoK is unlikely to pivot from its tightening as they are still committing to curb inflation as of now. The current monetary policy trends and inflation outlooks are visible in the chart aside, that represents indeed the policy rates together with the CPI index in the last few years. Last but not least, the global macro environment is also recently dominated by a very strong dollar. The dollar’s strength against the won adversely affects the trade balance, which is one of the pillars of Korea’s economy, and boosts import prices, thereby adding fuel to the skyrocketing domestic inflation: this is an opinion expressed by the Korea Capital Market Institute, that also remarks how a wave of corporate defaults is likely to lie ahead due to the aggravated liquidity and the unusually high credit spreads.

The Policy response

It is undoubtedly insightful to analyze what has been the policy makers response to the credit crunch.

On one hand, The Korean government announced a Won50tn (approx. $36bn) package to shore up credit markets last month, under which it will buy a wide range of bonds and commercial paper to stabilize the market. More in detail, the program (1) doubles the ceiling of its corporate bond-buying facility operated by special state-owned banks to 16 trillion won; (2) includes commercial paper issued by securities firms in the facility’s purchase list and (3) adds 3tn of additional liquidity for firms experiencing liquidity shortages. It is also relevant to note that the full amount of debt (205 billion won) will be repaid by Gangwon Province, the state guarantor of GJC's debt by the 15th of December, action which is expected to contribute to calming the markets: "The decision (to repay the debt) has been coordinated with the government including the Ministry of Economy and Finance," said Jeong Kwang-yeol, deputy governor on economic affairs for Gangwon Province.

On the other hand, the Bank of Korea has also taken some micro-policy measures, such as temporarily loosening the collateral policies for local financial institutions applying for loans and carrying out a temporary repurchase agreement with an estimated amount of 6 trillion won ($4.24 billion) to ensure the functioning of financial markets. Also, the plan to raise the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) from 70% to 80% will be postponed by three months to May 2023.

Even if the Bank of Korea did not directly inject liquidity into the economy, these measures are still contradictory to the action taken by the bank just days before the default of GJC, namely raising the benchmark interest rates in order to curb inflation.

Economic outlook

The Legoland situation is too big of an event on the political and economic scene of South Korea to remain an isolated happening with no future implications. The South Korean economy is and will most likely continue to be shaken due to one keyword: trust. The abrupt downgrade of the GJC bonds from an A1 rating to junk due to Gangwon’s newly elected conservative governor, Kim Jin-tae’s statement is a perfect example of how politics is a central component of a country’s economy and can build and demolish the trust of investors and citizens, and thus dictate the future of economic growth. Even though analysts expect the liquidity crunch event is likely to transform into a recession rather than a crisis, it is useful to analyze the new predictions about the South Korean economy.

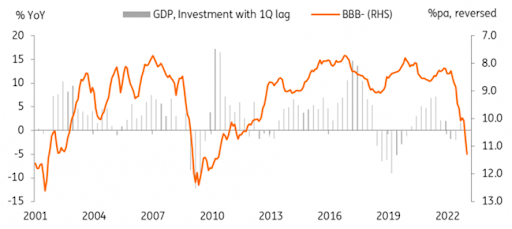

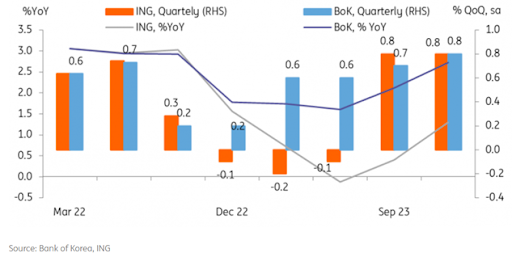

ING analysts expect a further deterioration in consumer sentiment and forecast negative consumer spending at least in the following quarter due to the burden of debt service on private consumption. The already-announced and future expected hikes in interest rates, together with the sentiment and market effects of the Legoland event will surely contribute to a fall in investment in the next quarters.

It is undoubtedly insightful to analyze what has been the policy makers response to the credit crunch.

On one hand, The Korean government announced a Won50tn (approx. $36bn) package to shore up credit markets last month, under which it will buy a wide range of bonds and commercial paper to stabilize the market. More in detail, the program (1) doubles the ceiling of its corporate bond-buying facility operated by special state-owned banks to 16 trillion won; (2) includes commercial paper issued by securities firms in the facility’s purchase list and (3) adds 3tn of additional liquidity for firms experiencing liquidity shortages. It is also relevant to note that the full amount of debt (205 billion won) will be repaid by Gangwon Province, the state guarantor of GJC's debt by the 15th of December, action which is expected to contribute to calming the markets: "The decision (to repay the debt) has been coordinated with the government including the Ministry of Economy and Finance," said Jeong Kwang-yeol, deputy governor on economic affairs for Gangwon Province.

On the other hand, the Bank of Korea has also taken some micro-policy measures, such as temporarily loosening the collateral policies for local financial institutions applying for loans and carrying out a temporary repurchase agreement with an estimated amount of 6 trillion won ($4.24 billion) to ensure the functioning of financial markets. Also, the plan to raise the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) from 70% to 80% will be postponed by three months to May 2023.

Even if the Bank of Korea did not directly inject liquidity into the economy, these measures are still contradictory to the action taken by the bank just days before the default of GJC, namely raising the benchmark interest rates in order to curb inflation.

Economic outlook

The Legoland situation is too big of an event on the political and economic scene of South Korea to remain an isolated happening with no future implications. The South Korean economy is and will most likely continue to be shaken due to one keyword: trust. The abrupt downgrade of the GJC bonds from an A1 rating to junk due to Gangwon’s newly elected conservative governor, Kim Jin-tae’s statement is a perfect example of how politics is a central component of a country’s economy and can build and demolish the trust of investors and citizens, and thus dictate the future of economic growth. Even though analysts expect the liquidity crunch event is likely to transform into a recession rather than a crisis, it is useful to analyze the new predictions about the South Korean economy.

ING analysts expect a further deterioration in consumer sentiment and forecast negative consumer spending at least in the following quarter due to the burden of debt service on private consumption. The already-announced and future expected hikes in interest rates, together with the sentiment and market effects of the Legoland event will surely contribute to a fall in investment in the next quarters.

On the exports side, the economic slowdown around the world’s most important nations, including the US, EU, and China will continue to determine a reduction in the levels of exports at least until 1H2023. As a result of all these factors, ING analysts forecast that the next three quarters, including the current one, will be characterized by economic contraction.

It is undoubted that measures have been taken to tackle the situation, but it is yet to be seen if this will be resolutive or just represent a short relief. What are the expectations right now? Investors are watching whether the loss of trust in South Korea's corporate bonds will spill over into stock and foreign exchange markets as well. In the meanwhile, BoK has decided to hike interest rates again on November 24th, though only by 25 basis points, hitting below the expected rise of 50 bps, and softening its communicative style so as to open to a more moderate policy in the upcoming months. This is in line with the commitment to stabilize prices as inflation is persistent and upside risks remain high, trying to balance this with the need to calm down the market about the credit market squeeze.

Other economists highlight the structural solidity of the Korean economy fundamentals, and how unlikely it is for this credit crunch to lead to large-scale insolvency of the corporate bond market (this is the opinion, for instance, of Kang Min-joo, senior economist for Korea and Japan at ING).

To wrap up, policy response has been present, and major crises are not on the horizon, hopefully. It is not to expect that the credit crunch will pose a systemic risk to the financial system because corporate’s debt conditions have improved on average compared to the past and most of them are already in risk management mode. But, this will hurt near-term growth and drag the economy into significant slowdown, increasing by far the yet likely outcome of a recession.

Conclusion

To conclude, South Korea is a miracle in economic history that in less than a century has risen from the world periphery to the G20. But it is also an example of how strong economies, in periods of crisis as the one we are now living, with a multitude of economic shocks coming one after another and infringing systematically the expectations of analysts, can go into crisis even due to an event that at least at a first sight my seem minor in nature.

Not only this, but South Korea has also evidenced how a timely policy response, both fiscal and monetary, is crucial to prevent crises from escalating. Despite the fundamentals are strong, the economic outlook is still articulated.

It is to be seen what the next year will bring in terms of aggregate output and markets performance in this Asian tiger. Nonetheless, it is likely that, in a climate of rising interest rates worldwide and most advanced economies, especially in the West, likely to face a recession in the short-medium term, these stress tests on capital markets became more and more frequent. While investors in uncertain times tend to fly to quality, policymakers must act minding experience from past crises to navigate their economies during stormy times.

One thing is certain: intense times are on the horizon.

Written by Marco Berardi, Roberto Fani, Livia Figarolo di Groppello, Ema Melihov

SOURCES

Other economists highlight the structural solidity of the Korean economy fundamentals, and how unlikely it is for this credit crunch to lead to large-scale insolvency of the corporate bond market (this is the opinion, for instance, of Kang Min-joo, senior economist for Korea and Japan at ING).

To wrap up, policy response has been present, and major crises are not on the horizon, hopefully. It is not to expect that the credit crunch will pose a systemic risk to the financial system because corporate’s debt conditions have improved on average compared to the past and most of them are already in risk management mode. But, this will hurt near-term growth and drag the economy into significant slowdown, increasing by far the yet likely outcome of a recession.

Conclusion

To conclude, South Korea is a miracle in economic history that in less than a century has risen from the world periphery to the G20. But it is also an example of how strong economies, in periods of crisis as the one we are now living, with a multitude of economic shocks coming one after another and infringing systematically the expectations of analysts, can go into crisis even due to an event that at least at a first sight my seem minor in nature.

Not only this, but South Korea has also evidenced how a timely policy response, both fiscal and monetary, is crucial to prevent crises from escalating. Despite the fundamentals are strong, the economic outlook is still articulated.

It is to be seen what the next year will bring in terms of aggregate output and markets performance in this Asian tiger. Nonetheless, it is likely that, in a climate of rising interest rates worldwide and most advanced economies, especially in the West, likely to face a recession in the short-medium term, these stress tests on capital markets became more and more frequent. While investors in uncertain times tend to fly to quality, policymakers must act minding experience from past crises to navigate their economies during stormy times.

One thing is certain: intense times are on the horizon.

Written by Marco Berardi, Roberto Fani, Livia Figarolo di Groppello, Ema Melihov

SOURCES

- Fianncial Times

- Kcmi

- Koreaherald

- Oxford academic

- Reuters

- The Economist