Special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) are in the list of those financial innovations that are hardly new, but that are now back, stronger than ever, and Italy knows it very well. The idea behind a SPAC is simple: these so-called blank cheque companies raise cash through an IPO and then deploy it later, by buying an as-yet-unidentified company.

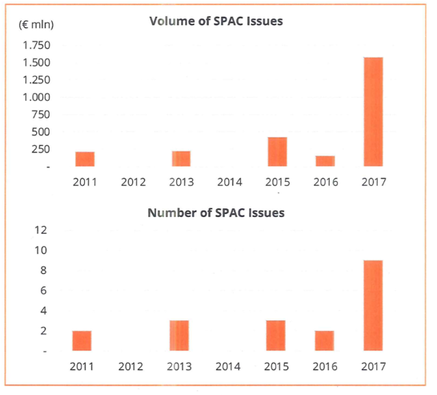

In Italy SPACs are all the rage: in the last 5-6 years this relatively new type of investment has attracted an increasingly long list of ex top managers, lawyers, bankers, top consultants have embarked on it. 2017 has been a buoyant year for SPACs on the Italian Stock Exchange: 8 of them were listed on AIM in 2017 (vs. 2 in 2016), for a total value of €1.1 bn (+620% vs 2016). Only one SPAC issue on MTA in 2017 (vs 0 in 2016): Space4 for a total value of €500m (See Exhibit 1).

In Italy SPACs are all the rage: in the last 5-6 years this relatively new type of investment has attracted an increasingly long list of ex top managers, lawyers, bankers, top consultants have embarked on it. 2017 has been a buoyant year for SPACs on the Italian Stock Exchange: 8 of them were listed on AIM in 2017 (vs. 2 in 2016), for a total value of €1.1 bn (+620% vs 2016). Only one SPAC issue on MTA in 2017 (vs 0 in 2016): Space4 for a total value of €500m (See Exhibit 1).

This year started off with a big bang: SPAXS, sponsored by Bob Diamond (the former Barclays chief executive) and Corrado Passera (the former head of Italy’s Intesa Sanpaolo and ex-minister), was listed at the beginning of February for a total value of 600 mln. Mr. Passera explains that the objective “is to turn a small bank into an online lender to small businesses and a merchant bank, which will buy non-performing loans from other banks and parcel them up before selling them on to institutional investors.”

Since their arrival in Italy and up to now, the 25 Italian SPACs have collected funds for €3.5bn and this amazing growth does not seem anywhere near to slowing down.

In order not to fall behind, it is crucial to understand the causes and the effects of this success, starting from the basics of this type of investment vehicle.

The logic behind a SPAC is quite simple: it is an empty vehicle promoted by a group of managers who raises funds through the issuance to the public of “units” consisting usually in a stock and a warrant (which can be used to buy later additional shares). At this point the SPAC has typically a period of two years to seek and find an attractive deal and conclude the acquisition of a target company (the so-called business combination).

Once the merger with the target company is concluded, the SPAC takes the name of the latter which becomes automatically a publicly traded company without having to go through the traditional iter of IPO. Conversely, if no deal materialises within the agreed period, the SPAC is liquidated and investors get their money back.

The link with a more traditional investment in a private equity fund is evident, even if we might consider a SPAC as a much more investor-centred solution. Greater advantages for the investor concern the lack of management fees during the period from the IPO to the business combination, the greater liquidity of the investment (since they’re listed), and the possibility for the investor to have a say in the choice of the target company (since the business combination has to be approved by shareholders with given majority and those that are against the decision have always the right to withdraw).

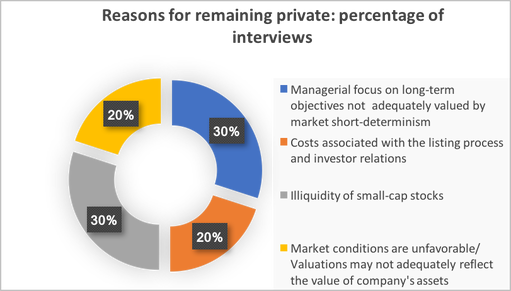

The advantages are numerous, but an even more interesting question might arise: are SPACs just a possibly good financial investment or could they have an impact on the real economy? In other words, we are asking ourselves whether an advantage may exist also from the target companies’ viewpoint, and more specifically, if this phenomenon can facilitate the access of companies to the capital market. In order to answer to this question, it could be useful to look at the main reasons why companies decide to stay private. Indeed, researches - built on a focus group of Italian firms – show that the main concerns are related to the listing process and its outcome, rather than the listed status itself (See Exhibit 2).

Since their arrival in Italy and up to now, the 25 Italian SPACs have collected funds for €3.5bn and this amazing growth does not seem anywhere near to slowing down.

In order not to fall behind, it is crucial to understand the causes and the effects of this success, starting from the basics of this type of investment vehicle.

The logic behind a SPAC is quite simple: it is an empty vehicle promoted by a group of managers who raises funds through the issuance to the public of “units” consisting usually in a stock and a warrant (which can be used to buy later additional shares). At this point the SPAC has typically a period of two years to seek and find an attractive deal and conclude the acquisition of a target company (the so-called business combination).

Once the merger with the target company is concluded, the SPAC takes the name of the latter which becomes automatically a publicly traded company without having to go through the traditional iter of IPO. Conversely, if no deal materialises within the agreed period, the SPAC is liquidated and investors get their money back.

The link with a more traditional investment in a private equity fund is evident, even if we might consider a SPAC as a much more investor-centred solution. Greater advantages for the investor concern the lack of management fees during the period from the IPO to the business combination, the greater liquidity of the investment (since they’re listed), and the possibility for the investor to have a say in the choice of the target company (since the business combination has to be approved by shareholders with given majority and those that are against the decision have always the right to withdraw).

The advantages are numerous, but an even more interesting question might arise: are SPACs just a possibly good financial investment or could they have an impact on the real economy? In other words, we are asking ourselves whether an advantage may exist also from the target companies’ viewpoint, and more specifically, if this phenomenon can facilitate the access of companies to the capital market. In order to answer to this question, it could be useful to look at the main reasons why companies decide to stay private. Indeed, researches - built on a focus group of Italian firms – show that the main concerns are related to the listing process and its outcome, rather than the listed status itself (See Exhibit 2).

The process underlying this “backdoor offering” allows target companies to avoid a big share of these problems. As for the costs related to an IPO process, they are only incurred by the SPAC when it is listed and the target company basically turns into a public company without having to bear any of them.

Beside this, there are many other problems which mainly arise from the fact that an IPO is a long procedure, and much of the outcome is uncertain when it is firstly started. In practice, the firm may end up with valuations that do not adequately reflect the value estimated by the entrepreneur. Market conditions also can turn adverse to the company once the intention to go public has already been announced, ultimately leading to the withdrawal of the offer. Indeed, this peculiar process of going public has clearly the advantage of transferring the “settlement” risk of the IPO from the company to the SPAC.

Further, the SPAC has already raised the funds, therefore the advantage is that the management team can negotiate the deal on a one-to-one basis. As a consequence, there is no uncertainty about valuation: the price negotiated by the parties corresponds exactly to what the target gets. Conversely, in an IPO the process is far more convoluted, with roadshows, press scrutiny and the need to convince multiple investors to buy at a certain price.

Finally, even if the deal does not go through, since all the negotiations between the SPAC and the target company are conducted in a private form, the firm is not impacted by any negative publicity.

Italian SPACs are continuously setting new records. They have many advantages and it’s really difficult to find any flaws. Finally, not only is it a smart form of investment, but it can also have many spillovers on the real economy and there’s good evidence that it can actually contribute to facilitate the listing procedure of private companies.

Beside this, there are many other problems which mainly arise from the fact that an IPO is a long procedure, and much of the outcome is uncertain when it is firstly started. In practice, the firm may end up with valuations that do not adequately reflect the value estimated by the entrepreneur. Market conditions also can turn adverse to the company once the intention to go public has already been announced, ultimately leading to the withdrawal of the offer. Indeed, this peculiar process of going public has clearly the advantage of transferring the “settlement” risk of the IPO from the company to the SPAC.

Further, the SPAC has already raised the funds, therefore the advantage is that the management team can negotiate the deal on a one-to-one basis. As a consequence, there is no uncertainty about valuation: the price negotiated by the parties corresponds exactly to what the target gets. Conversely, in an IPO the process is far more convoluted, with roadshows, press scrutiny and the need to convince multiple investors to buy at a certain price.

Finally, even if the deal does not go through, since all the negotiations between the SPAC and the target company are conducted in a private form, the firm is not impacted by any negative publicity.

Italian SPACs are continuously setting new records. They have many advantages and it’s really difficult to find any flaws. Finally, not only is it a smart form of investment, but it can also have many spillovers on the real economy and there’s good evidence that it can actually contribute to facilitate the listing procedure of private companies.

Giacomo Longoni