During last year, financial markets experienced a spike in the number of Special Purpose Acquisitions Companies. Just in 2020, a total of 248 SPACs took place, raising a record US$83.34 billion with an increase of over 400% compared to 2019.

SPACs, the acronym for Special Purpose Acquisitions Company, are also called “blank check” companies. They are newly-constituted companies with no commercial purpose. The only goal is to raise capital for IPOs or to buy and reverse merging with a private company. Most of SPACs are listed in U.S. stock exchanges, where the listing rules oblige them to identify a target business and complete the merge within two years after their opening. The surge of newly listed SPACs in 2020 indicates that more and more companies are looking for target businesses to acquire by the end of 2022, namely to “de-SPAC”. Moreover, thanks to governments investing trillions of dollars to offset the economic effects of the pandemic, the SPAC mania will inevitably continue, creating a huge number of M&A opportunities.

SPACs Advantages and DE-SPAC-ING

A reverse-merger with a SPAC allows a private company to go public, via an already listed parent company – the Special Purpose Acquisition Company. This listing route offers a quicker track to IPO than undertaking the traditional underwriting and compliance process. There are some compelling reasons for a company to participate in a SPAC deal rather than private equity funding or traditional IPOs. First of all, deals are identified in advance, and the valuation is agreed by both parties. The target firm can be certain the transaction will occur, at an agreed value. Public companies are negotiated at higher multiples than private ones, therefore SPACs offer the chance for higher valuation. Moreover, these deals are relatively faster to finalize: just 2-3 months compared to 2-3 years necessary for an IPO. Lastly, the acquirer company pays for most of the costs and raises cash for the transaction, making the whole listing process cheaper and more “liquid” for the firm.

For the aforementioned reasons, SPAC may be a convenient listing choice for startups and IPO-ready unicorns in high-growth sectors such as tech, Fintech and healthcare. Valuation is particularly crucial for start-ups. In sectors with scarceness of comparable firms or characterized by a lot of uncertainty, target firms may benefit from valuation defined by private negotiations between the acquirer and the target, as in SPAC deals.

While the SPAC trend went on for the whole 2020, a total 56$ billion in de-SPAC transactions took place last year and will surely continue for the foreseeable future. As a matter of facts, SPACs that cannot identify and merge with a target within their two-year deadline, will become defunct. Goldman Sachs’ analysts foresee more than $500 billions of M&As in de-SPAC transactions, increasing their initial outlook of around $300 billion. SPAC sponsors are currently looking for and competing to attract target firms, especially in high-growth sectors.

Will Asia be the next hotspot?

Asia-Pacific, where tech startups thrive on economic growth, is the place-to-be for listed SPACs in 2021.

This region, and more specifically Southeast Asia, is experiencing a growing interest because tech-focused startups view SPACs as a more efficient 'exit' option than conventional listings. Counting on many Southeast Asian unicorns willing to go public, U.S. SPAC sponsors on the hunt for targets have many options. Singaporean Grab, Indonesia food delivery unicorn Go-Jek, and e-commerce firm Bukalapak are de-SPAC targets under scrutiny. Indonesian online travel app Traveloka is reportedly considering a “SPAC listing” too.

APAC is not only regarded as the market where U.S. investors will de-SPAC, creating its own SPAC trend. Antony Leung, former Hong Kong finance secretary and Blackstone executive has been the major driver, launching his own SPAC back in 2018.

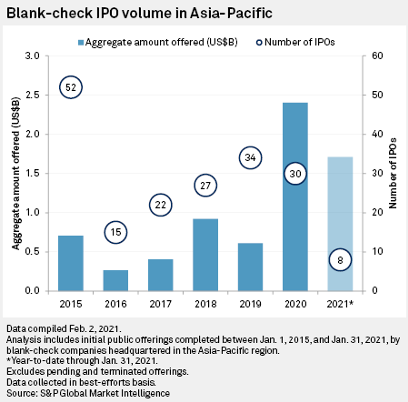

Asia-Pacific-headquartered SPACs collected $2.4 billion in 2020, significantly improving $613 million of funding raised in 2019. That number will certainly increase in 2021: as of the end of January, eight SPACs have already raised $1.71 billion.

SPACs, the acronym for Special Purpose Acquisitions Company, are also called “blank check” companies. They are newly-constituted companies with no commercial purpose. The only goal is to raise capital for IPOs or to buy and reverse merging with a private company. Most of SPACs are listed in U.S. stock exchanges, where the listing rules oblige them to identify a target business and complete the merge within two years after their opening. The surge of newly listed SPACs in 2020 indicates that more and more companies are looking for target businesses to acquire by the end of 2022, namely to “de-SPAC”. Moreover, thanks to governments investing trillions of dollars to offset the economic effects of the pandemic, the SPAC mania will inevitably continue, creating a huge number of M&A opportunities.

SPACs Advantages and DE-SPAC-ING

A reverse-merger with a SPAC allows a private company to go public, via an already listed parent company – the Special Purpose Acquisition Company. This listing route offers a quicker track to IPO than undertaking the traditional underwriting and compliance process. There are some compelling reasons for a company to participate in a SPAC deal rather than private equity funding or traditional IPOs. First of all, deals are identified in advance, and the valuation is agreed by both parties. The target firm can be certain the transaction will occur, at an agreed value. Public companies are negotiated at higher multiples than private ones, therefore SPACs offer the chance for higher valuation. Moreover, these deals are relatively faster to finalize: just 2-3 months compared to 2-3 years necessary for an IPO. Lastly, the acquirer company pays for most of the costs and raises cash for the transaction, making the whole listing process cheaper and more “liquid” for the firm.

For the aforementioned reasons, SPAC may be a convenient listing choice for startups and IPO-ready unicorns in high-growth sectors such as tech, Fintech and healthcare. Valuation is particularly crucial for start-ups. In sectors with scarceness of comparable firms or characterized by a lot of uncertainty, target firms may benefit from valuation defined by private negotiations between the acquirer and the target, as in SPAC deals.

While the SPAC trend went on for the whole 2020, a total 56$ billion in de-SPAC transactions took place last year and will surely continue for the foreseeable future. As a matter of facts, SPACs that cannot identify and merge with a target within their two-year deadline, will become defunct. Goldman Sachs’ analysts foresee more than $500 billions of M&As in de-SPAC transactions, increasing their initial outlook of around $300 billion. SPAC sponsors are currently looking for and competing to attract target firms, especially in high-growth sectors.

Will Asia be the next hotspot?

Asia-Pacific, where tech startups thrive on economic growth, is the place-to-be for listed SPACs in 2021.

This region, and more specifically Southeast Asia, is experiencing a growing interest because tech-focused startups view SPACs as a more efficient 'exit' option than conventional listings. Counting on many Southeast Asian unicorns willing to go public, U.S. SPAC sponsors on the hunt for targets have many options. Singaporean Grab, Indonesia food delivery unicorn Go-Jek, and e-commerce firm Bukalapak are de-SPAC targets under scrutiny. Indonesian online travel app Traveloka is reportedly considering a “SPAC listing” too.

APAC is not only regarded as the market where U.S. investors will de-SPAC, creating its own SPAC trend. Antony Leung, former Hong Kong finance secretary and Blackstone executive has been the major driver, launching his own SPAC back in 2018.

Asia-Pacific-headquartered SPACs collected $2.4 billion in 2020, significantly improving $613 million of funding raised in 2019. That number will certainly increase in 2021: as of the end of January, eight SPACs have already raised $1.71 billion.

CITIC Capital, a Chinese investment advisory firm, raised 240$ million in 2020, becoming the first Chinese state-owned firm to launch a SPAC. The firm is now on the hunt for targets in the energy efficiency, clean technology and sustainability sectors. SoftBank, the Asian investment colossus, joined the trend as well. A SoftBank-backed SPAC closed its IPO on Jan. 13, collecting proceeds for US$603.8 million.

As to facilitate Asian-backed SPACs, Singapore’s stock exchange is willing to allow SPAC listing, and it began background regulatory consultations. The Singaporean Bourse may turn to be the first Asian stock exchange to permit SPAC listings. The rationale behind this revolution for Asian stock markets is rumored to be a strife with the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, currently the leader in tech IPOs in Asia. Nevertheless, Asian startups are keen on exploiting the SPAC wave regardless the stock exchanges that will emerge as the SPAC hub in the region.

As to facilitate Asian-backed SPACs, Singapore’s stock exchange is willing to allow SPAC listing, and it began background regulatory consultations. The Singaporean Bourse may turn to be the first Asian stock exchange to permit SPAC listings. The rationale behind this revolution for Asian stock markets is rumored to be a strife with the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, currently the leader in tech IPOs in Asia. Nevertheless, Asian startups are keen on exploiting the SPAC wave regardless the stock exchanges that will emerge as the SPAC hub in the region.

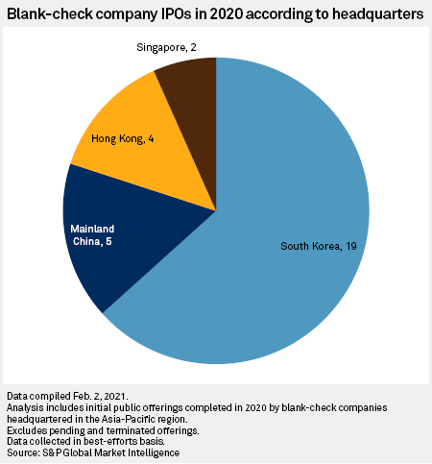

According to S&P, South Korea is well positioned, way ahead of the other Asian countries in the SPAC boom, counting 19 listings in 2020, in comparison with 5 Chinese listings, 4 in Hong Kong and 2 in Singapore.South Korea can indeed count on regulations about SPAC listing since a long time, to the extent that the first deal took place in 2010.

Even though there are still concerns around the sustainability of the global SPAC boom, South-east Asian companies are increasingly looking to this type of deal to drive their expansion. SPACs could therefore well become a key element in the region’s post-pandemic economic reinvention.

Elena Donati

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

Even though there are still concerns around the sustainability of the global SPAC boom, South-east Asian companies are increasingly looking to this type of deal to drive their expansion. SPACs could therefore well become a key element in the region’s post-pandemic economic reinvention.

Elena Donati

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.