What should we expect in the future?

According to Fumagalli (2014), SPACs as investment vehicles will not be enough to solve the chronic Italian scarcity of IPOs in regulated markets, as the reasons of this phenomenon are profoundly intrinsic to the way capitalism has evolved in our country. Nonetheless, the transactions so far described have raised the interest of many operators and it is sure that SPACs will continue to be created, even if some evolutive trends seem likely.

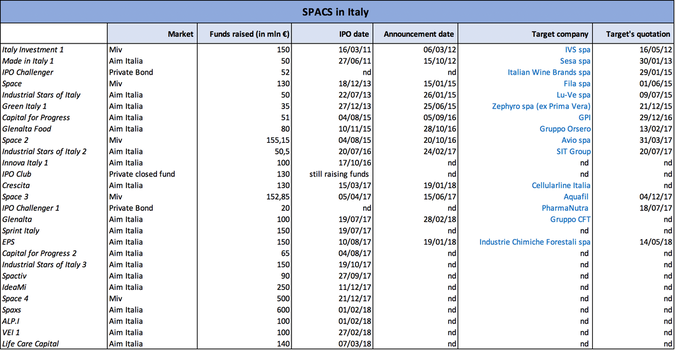

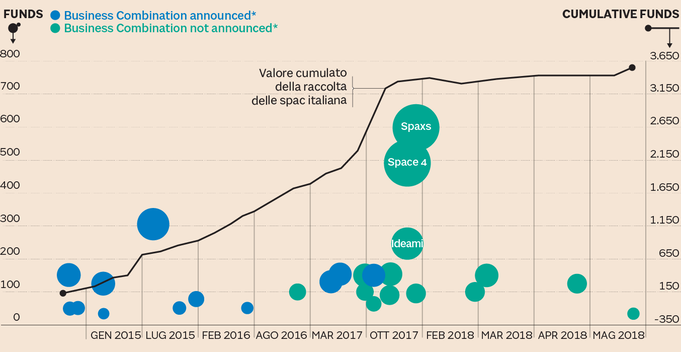

Among these, it is predictable the emergence of specialized SPACs, i.e. with the aim of finding their target in a specific industry. An example of this is represented by Glenalta food, dedicated to the food & beverage industry. This will, in turn, cause two phenomena: promoters with a more accentuated specific experience and industrial skill’s set, and bigger dimension for SPACs, with an increasing interest for targets outside national borders. Promoters coming from the industrial rather than the financial world will probably provide an higher managerial support to target companies especially in the period after business combination, but they will accentuate the non-repetitive nature of these initiatives. On the other hand, bigger SPACs require higher capital at risk for their founders. This trend is already evident today, especially for the cases of Space 4 and Spaxs. It is so possible that the resources of institutional investors with an high risk profile will take a more important role in financing these vehicles. However, the participation to the capital at risk of other subjects than the management team itself, reducing the “skin in the game” of the latter, would probably be an element not appreciated by the market.

Recurring is also the theme of creating SPACs with a longer life span than a single business combination, with the possibility of using the funds collected in subsequent trances, becoming sort of consolidators for specific industries or niches of business. Even if it seems a suggestive idea, there may be complications to its implementation (as the fact that shareholders would have to vote subsequent transactions) making it still impracticable. Another possibility is to have a SPAC executing a business combination with many target companies at the same time, but this hypothesis as well, even if attractive, seems very complex in terms of negotiation among multilateral parties.

From investors’ point of view, it is possible that in the future the pressure to initiatives more favorable to them will gradually bring to a sharing of promoters’ carried interest. As SPACs increase in number, investors will become more and more selective and the crucial competitive element will not be the percentage of funds granted to investors not approving the business combination, but the limits to promoters’ benefits. It is also reasonable to suppose a more specific nature in the types of investors of SPACs’ transactions. Indeed, international investors interested in particular sectors will have the chance to easily convey their funds in credible initiatives and balanced structures.

In these first initiatives investors have not asked an independent opinion regarding the proposed business combination. This was also due to the fact that the majority of them were institutional investors able to form their own judgement about target companies. Nonetheless, in the future, it would not be unreasonable for SPACs to give access to investors, through organized forms of coordination entrusted to independent administrators, of an independent opinion regarding the transaction, the cost of which would have to be sustained by the SPAC.

In addition, it is possible that in the future the coordination among investors will bring to negotiations with management teams in order to obtain better conditions in the context of the business combination, as it has already been observed in the US. This appears today unlikely as these actions are usually fostered by third operators (advisors, independent boutiques), which are lacking in our country.

Recurring is also the theme of creating SPACs with a longer life span than a single business combination, with the possibility of using the funds collected in subsequent trances, becoming sort of consolidators for specific industries or niches of business. Even if it seems a suggestive idea, there may be complications to its implementation (as the fact that shareholders would have to vote subsequent transactions) making it still impracticable. Another possibility is to have a SPAC executing a business combination with many target companies at the same time, but this hypothesis as well, even if attractive, seems very complex in terms of negotiation among multilateral parties.

From investors’ point of view, it is possible that in the future the pressure to initiatives more favorable to them will gradually bring to a sharing of promoters’ carried interest. As SPACs increase in number, investors will become more and more selective and the crucial competitive element will not be the percentage of funds granted to investors not approving the business combination, but the limits to promoters’ benefits. It is also reasonable to suppose a more specific nature in the types of investors of SPACs’ transactions. Indeed, international investors interested in particular sectors will have the chance to easily convey their funds in credible initiatives and balanced structures.

In these first initiatives investors have not asked an independent opinion regarding the proposed business combination. This was also due to the fact that the majority of them were institutional investors able to form their own judgement about target companies. Nonetheless, in the future, it would not be unreasonable for SPACs to give access to investors, through organized forms of coordination entrusted to independent administrators, of an independent opinion regarding the transaction, the cost of which would have to be sustained by the SPAC.

In addition, it is possible that in the future the coordination among investors will bring to negotiations with management teams in order to obtain better conditions in the context of the business combination, as it has already been observed in the US. This appears today unlikely as these actions are usually fostered by third operators (advisors, independent boutiques), which are lacking in our country.

In conclusion, the standardization of SPACs’ functioning structures is another issue of great importance. The first enterprises show an high heterogeneity especially for the accrual period of promoters’ carried interest. It could be argued that less prestigious promoters should have to offer more “investor friendly” conditions or that specialized SPACs should require particular structures. For example, think of an initiative directed to a pharma or life science target company, where the maturation of the pipeline of new products needs long periods of time: the merit of promoters would be in the identification of the potentialities of such pipelines, but in order to get the benefits of such expertise a long-time temporal horizon would have to be guaranteed.

At the current state, it is difficult to identify in the different structures adopted reasons different from the need of differentiating themselves and a certain desire of novelty typical of every marketing activity ( even those relative to financial instruments).

Daniel Sacco

At the current state, it is difficult to identify in the different structures adopted reasons different from the need of differentiating themselves and a certain desire of novelty typical of every marketing activity ( even those relative to financial instruments).

Daniel Sacco