Not oil, not China, not the Fed. But the latent issue of the student loan market. A market which has disproportionately grown over the years and whose growth might resemble that of the pre-crisis housing market.

The purpose of the article is that of drawing some parallels between what we all know as the housing bubble characterizing the GFC and what is referred to as student loan bubble. These two phenomena, as we will see in further detail throughout the article, share some common features. These similarities are scaring those who are aware of the situation and are going to surprise those who are not yet so.

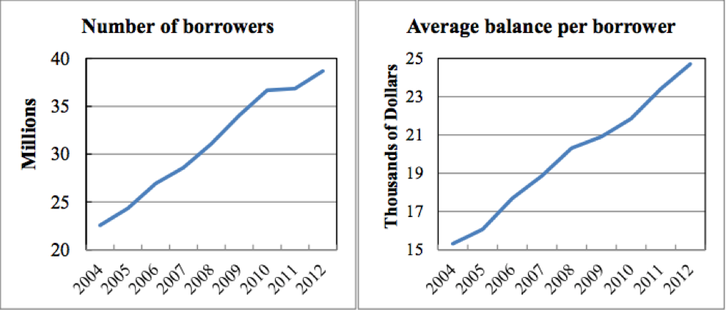

Student loan debt has doubled since 2007 and enjoyed a five-year average growth of 11 percent, compared with 12 percent of mortgage debt during the peak debt level. The current value of student loan debt outstanding in the US amounts to $1.2 trillion, with million borrowers and an average debt balance of $29,000. As shown in the graph, the magnitude of these figures is steadily growing.

Such extraordinary growth has been partly fueled by society and government that put a high value on education as an instrument to achieve life success. Here is where it lies a first similarity with the subprime mortgage market growth. Furthermore, the expansion of both industries is rooted on artificially low rates for the first years. Such rates then catch up and exponentially increase over the years. Recent studies show that interest rates on private student loans can float in the wide range of 5% to 18%.

The purpose of the article is that of drawing some parallels between what we all know as the housing bubble characterizing the GFC and what is referred to as student loan bubble. These two phenomena, as we will see in further detail throughout the article, share some common features. These similarities are scaring those who are aware of the situation and are going to surprise those who are not yet so.

Student loan debt has doubled since 2007 and enjoyed a five-year average growth of 11 percent, compared with 12 percent of mortgage debt during the peak debt level. The current value of student loan debt outstanding in the US amounts to $1.2 trillion, with million borrowers and an average debt balance of $29,000. As shown in the graph, the magnitude of these figures is steadily growing.

Such extraordinary growth has been partly fueled by society and government that put a high value on education as an instrument to achieve life success. Here is where it lies a first similarity with the subprime mortgage market growth. Furthermore, the expansion of both industries is rooted on artificially low rates for the first years. Such rates then catch up and exponentially increase over the years. Recent studies show that interest rates on private student loans can float in the wide range of 5% to 18%.

Both industries are affected by a similarly wrong system of incentives. Lenders are encouraged to lend, and borrowers are encouraged to borrow. The formers generate upfront commissions and future interests, while the latter are now able to get an education that might pay back in the future. While for mortgage lending banks were supposed to assess the creditworthiness of the borrower based on different criteria, for student loans all it is required is the passing of a ridiculously simple aptitude test.

Once again, the government guarantees for such loans. In the subprime case were Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, in the student loan case is instead the US Department of Education. To the extent the borrower does not pay in a timely manner, the government is the only one bounded to pay.

The subprime mortgage industry was all but transparent, and the same can be said for some student loans. In a report from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (a US Government agency responsible for consumer protection in the financial sector) emerges that many borrowers have recently complained about the difficulties in finding the status of their payments, about available payment options and misplaced payments. A major issue reported was also the inability to take advantage of lower interest rates due to a lack of refinancing opportunities. Contract conditions are murky and naive borrowers are lured into taking on loans they could never afford to repay, unless of course their new education would prove extremely successful!!

However, despite striking similarities between the two industries, some differences can be identified.

As of today, the student loan market remains more isolated that what the subprime mortgage industry was back in 2008 because there is essentially no derivatives market for such products. This aspect makes the student loan market less risky than the subprime mortgage one. Indeed, the student loan performance only affects the counterparty directly involved in the transaction - in this case the lending bank - and does not hit other investors.

Additionally, some provide further reasons why student loans are safer than home mortgages. While it is true that home mortgages are collateralized, it is also true that the collateral is the actual house. This means that, when the bubble burst and the value of houses falls, the collateral is likely to be worth less than the value lent out. This is what happened in 2008, when subprime borrowers were better off walking away from their houses rather than repaying back their loans as they were given the option to do so.

With student loans there is nothing to walk away from. They have no collateral and are not dischargeable in bankruptcy. For this reason the borrower is bounded to pay, sooner or later.

The bottom line is, is it really so? Are we lacking of criticism and committing the same mistake we did back in 2008? Is the market believing in something which will reveal just wrong in a couple of years from now? Has the market learnt something from the past or is it damned to repeat it?

Federico Rendina