They say time kills all deals, but after almost 3 years after their first attempt to take Telecom Italia private, KKR seems to have finally found the magic formula: a $24 billion acquisition of TIM’s phone and internet network has been agreed to by the two companies. KKR can expand its already large portfolio of telecom companies and consolidate a relatively fragmented Italian communication sector, while TIM receives some much-needed cash to invest and pay off debt. But how does this play into KKR’s European ambitions, and how do Vivendi and Open Fiber fit in the picture?

KKR: a leader in the PE landscape

While none of KKR’s founders – Jerome Kohlberg, Henry Kravis and George Roberts - were blonde, the company still has surprisingly a lot in common with the English fairy tale of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears”: First of all, much like the main character in the story, KKR’s funds have been raised by 3 bears – 3 ex-employees of Bear Stearns, where they met in early 1970s. Secondly, KKR has long had a habit of hijacking deals and inviting themselves into other companies’ homes – a procedure funnily known as “Bear Hugging”. Thirdly and most importantly, while it might take a couple tries for KKR to land the right opportunity, when they do, they do it just right.

KKR was founded 1976 by Kohlberg and the cousin pair of Kravis and Roberts and quickly rose to the top of the private equity world: their inaugural fund raised just $25 million, but that did not stop the trio from parlaying that sum into more than $500 million profit. Soon enough, every investor wanted a piece of the pie, and a decade later, KKR’s funds totaled more than $2.4 billion. Fueled later by Drexel’s junk bond frenzy, KKR has landed some of the biggest deals even in today’s standards: Beatrice Foods ($8.7 billion), Safeway Stores ($4.8 billion) and without a doubt the crown jewel, RJR Nabisco’s $31.3 billion take-private deal – though this one had more media success than financial success. For a long time now, KKR has been at the forefront of private equity and in 2008 they established their Global Infrastructure Business, which, as of June 2022 oversaw almost $50 billion, a lot of which in telecom infrastructure.

Out of all previous deals in the sector, the fund’s $24 billion acquisition of Telecom Italia’s (TIM) fixed-line phone and internet network was anything but flawless: in 2021, KKR tried to take TIM private in what would have been Europe’s largest ever private equity buyout: $12.1 billion enterprise value and, including TIM’s $24.9 billion net debt, a deal worth $37 billion. That did not materialise, however, much to the delight of Vivendi, the French enterprise that is the largest shareholder into Italy’s main telecom company. Now, in 2023, KKR tried again, submitting a binding offer that was hastily accepted by the board without a shareholder vote. Two other large stakeholders in the deal had something to say: Italy’s government, which considers the asset as crucial to welfare of the country accepted to hold onto their veto power under the condition they take a 20% stake in TIM’s landline grid. On the other hand, Vivendi threatened to take legal action against TIM’s KKR deal, which TIM’s CEO, Pietro Labriola has called a key to investing within the company as well as outside it, which is “pivotal amid the current transformation within our sector”.

Tim: how did we get to this point?

Early Foundations and Political Shifts

TIM, formerly Telecom Italia, was founded among other four territorial-based companies in 1925 as Stipel, offering services in Lombardy, Piedmont and Aosta Valley regions. In 1964 a reforming centre-left government managed to merge the five concession-holders under the name of Sip, creating the first state-owned telecommunication company covering all the Italian territory.

In 1992, the political system, shaken by scandal and the indebtedness of the public sector, was in search of ways to balance the books. Simultaneously, there was a perceived need to conclude the era of state involvement, a fundamental aspect of the power structure, particularly associated with the Christian Democrats (DC) and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI).

In the discussion over the first privatization decree, a Senate commission recommended the formation of a “stable core” of shareholders who would represent around 18% of the capital of the group. Telecom Italia's initial IPO took place on 20th of October 1997, with shares trading at 10 908 lire, and with the Treasury gaining 26 thousand billion lire from the sale of 35.26% of the capital.

Telecom Italia's Ownership Chronicle: A Story of Missteps and Debt Burdens

The origin of the failure is represented by the government's primary error of limiting the involvement of domestic capital in the stable core. A mere 6.62% of shares were sold through direct negotiations, lacking a substantial premium, to a group of investors without significant industrial influence. The "hard core" included recently privatized banks, notably Mediobanca, each holding an average share of 0.5% of the total capital. Additionally, banking foundations associated with Catholic-origin savings banks, and the traditionally left-governed Tuscan bank Monte dei Paschi di Siena, were part of this core. While the American company AT&T and the European group Unisource were intended to serve as industrial partners – with reserved board seats anticipated prior to the deal's conclusion – this collaboration did not materialize. This prevented the formation of a stable ownership structure, with many negative consequences arising in the following years.

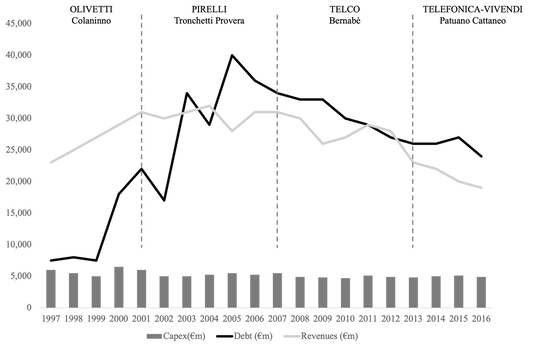

In 1999, Telecom Italia was taken over with a leveraged buyout by Bell, through which the CEO Roberto Colaninno and a group of small investors, mostly private, owned Olivetti, which in turn controlled 51% of the Italian telecommunication company.

From 2001, Marco Tronchetti Provera, with ownership in Pirelli, Edizione Holding and a combined investment of €7 billion, gained control of Telecom Italia, which, at the time, had a market capitalization of €55 billion and partially controlled TIM.

The problem with Telecom Italia’s privatization was born during Colaninno's takeover, a leveraged buyout funded by with nearly €50bn, which consequently brought part of the debt into Olivetti. The situation worsened when Pirelli and Edizione Holding's liquidity was used for control under Tronchetti Provera’s management. The reduction of the debt in both takeovers was tied to the notable capacity of Telecom Italia and TIM to generate funds, but those funds could not have been put back into Olivetti, still less others higher up the ownership structure.

Moreover, the new management of Tronchetti recognized overvalued assets acquired by the previous administration, leading to credit reduction and price renegotiation.

In 2003, a pivotal shift in corporate law legitimized the long-awaited merger between Olivetti and Telecom Italia. Despite this development, Tronchetti Provera's personal financial commitment to the cause amounted to less than 1% of Telecom's overall capital. While the restructuring facilitated the transfer of significant cash flows along the chain of his controlled companies, it permanently burdened Telecom Italia with substantial inherited debt.

The controlling group later facilitated Telecom Italia’s tender offer on TIM, aiming to unify fixed and mobile telephony after restructuring Olivetti's debt. The €14.5 billion takeover of TIM was launched and concluded in January 2005, financed with debt raised on Telecom, making it skyrocket up to €46.9 billion, further putting immense pressure on the stability of the company.

Redemption Attempts and the Rise of Vivendi

On April 28, an Italian-Spanish consortium, including Mediobanca, Generali, Intesa Sanpaolo, Sintonia, and Telefónica, made an offer to acquire Pirelli's stake, forming Telco S.p.A. to control about 23% of Telecom Italia and taking on a substantial €35.7 billion of debt burden. The offer was accepted in late April 2007 and on October 27, 2009, Telco shareholders renewed the control agreement for another three years.

Over the course of ten years, the various assembly, disassembly, and reassembly processes within the company have enriched a multitude of consultants. The cumulative cost incurred by the company for these consultancy services amounted to €4.75 billion, making it a significant consequence of the government’s failed privatization.

On September 23, 2013, following a historic low of €0.50 per share, Generali, Mediobanca, and Intesa Sanpaolo agreed to sell their Telco shares to Telefónica. This boosted the Spanish operator's stake in the holding controlling 22.4% of Telecom Italia from 46% to 66%.

During Telco's management (Telefónica, Mediobanca, Intesa, Generali) from 2007 to 2013, financial statements reflected a decrease in net debt (from €35.7 billion to €26.8 billion) and a decline in revenue (from €31.3 billion to €22.4 billion). This phase witnessed a shift in revenue composition, with a decrease in voice services (fixed and mobile) and growth in connectivity and value-added services.

From October 2015, Vivendi entered with a 20% ownership and increased board influence. This move secured three committee seats. Vivendi continued acquiring shares, reaching 24.9% on March 11, 2016, becoming the largest shareholder.

KKR: a leader in the PE landscape

While none of KKR’s founders – Jerome Kohlberg, Henry Kravis and George Roberts - were blonde, the company still has surprisingly a lot in common with the English fairy tale of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears”: First of all, much like the main character in the story, KKR’s funds have been raised by 3 bears – 3 ex-employees of Bear Stearns, where they met in early 1970s. Secondly, KKR has long had a habit of hijacking deals and inviting themselves into other companies’ homes – a procedure funnily known as “Bear Hugging”. Thirdly and most importantly, while it might take a couple tries for KKR to land the right opportunity, when they do, they do it just right.

KKR was founded 1976 by Kohlberg and the cousin pair of Kravis and Roberts and quickly rose to the top of the private equity world: their inaugural fund raised just $25 million, but that did not stop the trio from parlaying that sum into more than $500 million profit. Soon enough, every investor wanted a piece of the pie, and a decade later, KKR’s funds totaled more than $2.4 billion. Fueled later by Drexel’s junk bond frenzy, KKR has landed some of the biggest deals even in today’s standards: Beatrice Foods ($8.7 billion), Safeway Stores ($4.8 billion) and without a doubt the crown jewel, RJR Nabisco’s $31.3 billion take-private deal – though this one had more media success than financial success. For a long time now, KKR has been at the forefront of private equity and in 2008 they established their Global Infrastructure Business, which, as of June 2022 oversaw almost $50 billion, a lot of which in telecom infrastructure.

Out of all previous deals in the sector, the fund’s $24 billion acquisition of Telecom Italia’s (TIM) fixed-line phone and internet network was anything but flawless: in 2021, KKR tried to take TIM private in what would have been Europe’s largest ever private equity buyout: $12.1 billion enterprise value and, including TIM’s $24.9 billion net debt, a deal worth $37 billion. That did not materialise, however, much to the delight of Vivendi, the French enterprise that is the largest shareholder into Italy’s main telecom company. Now, in 2023, KKR tried again, submitting a binding offer that was hastily accepted by the board without a shareholder vote. Two other large stakeholders in the deal had something to say: Italy’s government, which considers the asset as crucial to welfare of the country accepted to hold onto their veto power under the condition they take a 20% stake in TIM’s landline grid. On the other hand, Vivendi threatened to take legal action against TIM’s KKR deal, which TIM’s CEO, Pietro Labriola has called a key to investing within the company as well as outside it, which is “pivotal amid the current transformation within our sector”.

Tim: how did we get to this point?

Early Foundations and Political Shifts

TIM, formerly Telecom Italia, was founded among other four territorial-based companies in 1925 as Stipel, offering services in Lombardy, Piedmont and Aosta Valley regions. In 1964 a reforming centre-left government managed to merge the five concession-holders under the name of Sip, creating the first state-owned telecommunication company covering all the Italian territory.

In 1992, the political system, shaken by scandal and the indebtedness of the public sector, was in search of ways to balance the books. Simultaneously, there was a perceived need to conclude the era of state involvement, a fundamental aspect of the power structure, particularly associated with the Christian Democrats (DC) and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI).

In the discussion over the first privatization decree, a Senate commission recommended the formation of a “stable core” of shareholders who would represent around 18% of the capital of the group. Telecom Italia's initial IPO took place on 20th of October 1997, with shares trading at 10 908 lire, and with the Treasury gaining 26 thousand billion lire from the sale of 35.26% of the capital.

Telecom Italia's Ownership Chronicle: A Story of Missteps and Debt Burdens

The origin of the failure is represented by the government's primary error of limiting the involvement of domestic capital in the stable core. A mere 6.62% of shares were sold through direct negotiations, lacking a substantial premium, to a group of investors without significant industrial influence. The "hard core" included recently privatized banks, notably Mediobanca, each holding an average share of 0.5% of the total capital. Additionally, banking foundations associated with Catholic-origin savings banks, and the traditionally left-governed Tuscan bank Monte dei Paschi di Siena, were part of this core. While the American company AT&T and the European group Unisource were intended to serve as industrial partners – with reserved board seats anticipated prior to the deal's conclusion – this collaboration did not materialize. This prevented the formation of a stable ownership structure, with many negative consequences arising in the following years.

In 1999, Telecom Italia was taken over with a leveraged buyout by Bell, through which the CEO Roberto Colaninno and a group of small investors, mostly private, owned Olivetti, which in turn controlled 51% of the Italian telecommunication company.

From 2001, Marco Tronchetti Provera, with ownership in Pirelli, Edizione Holding and a combined investment of €7 billion, gained control of Telecom Italia, which, at the time, had a market capitalization of €55 billion and partially controlled TIM.

The problem with Telecom Italia’s privatization was born during Colaninno's takeover, a leveraged buyout funded by with nearly €50bn, which consequently brought part of the debt into Olivetti. The situation worsened when Pirelli and Edizione Holding's liquidity was used for control under Tronchetti Provera’s management. The reduction of the debt in both takeovers was tied to the notable capacity of Telecom Italia and TIM to generate funds, but those funds could not have been put back into Olivetti, still less others higher up the ownership structure.

Moreover, the new management of Tronchetti recognized overvalued assets acquired by the previous administration, leading to credit reduction and price renegotiation.

In 2003, a pivotal shift in corporate law legitimized the long-awaited merger between Olivetti and Telecom Italia. Despite this development, Tronchetti Provera's personal financial commitment to the cause amounted to less than 1% of Telecom's overall capital. While the restructuring facilitated the transfer of significant cash flows along the chain of his controlled companies, it permanently burdened Telecom Italia with substantial inherited debt.

The controlling group later facilitated Telecom Italia’s tender offer on TIM, aiming to unify fixed and mobile telephony after restructuring Olivetti's debt. The €14.5 billion takeover of TIM was launched and concluded in January 2005, financed with debt raised on Telecom, making it skyrocket up to €46.9 billion, further putting immense pressure on the stability of the company.

Redemption Attempts and the Rise of Vivendi

On April 28, an Italian-Spanish consortium, including Mediobanca, Generali, Intesa Sanpaolo, Sintonia, and Telefónica, made an offer to acquire Pirelli's stake, forming Telco S.p.A. to control about 23% of Telecom Italia and taking on a substantial €35.7 billion of debt burden. The offer was accepted in late April 2007 and on October 27, 2009, Telco shareholders renewed the control agreement for another three years.

Over the course of ten years, the various assembly, disassembly, and reassembly processes within the company have enriched a multitude of consultants. The cumulative cost incurred by the company for these consultancy services amounted to €4.75 billion, making it a significant consequence of the government’s failed privatization.

On September 23, 2013, following a historic low of €0.50 per share, Generali, Mediobanca, and Intesa Sanpaolo agreed to sell their Telco shares to Telefónica. This boosted the Spanish operator's stake in the holding controlling 22.4% of Telecom Italia from 46% to 66%.

During Telco's management (Telefónica, Mediobanca, Intesa, Generali) from 2007 to 2013, financial statements reflected a decrease in net debt (from €35.7 billion to €26.8 billion) and a decline in revenue (from €31.3 billion to €22.4 billion). This phase witnessed a shift in revenue composition, with a decrease in voice services (fixed and mobile) and growth in connectivity and value-added services.

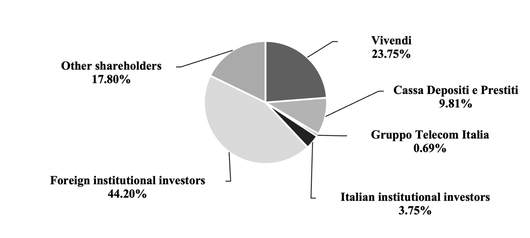

From October 2015, Vivendi entered with a 20% ownership and increased board influence. This move secured three committee seats. Vivendi continued acquiring shares, reaching 24.9% on March 11, 2016, becoming the largest shareholder.

Key financials in the period 1997-2016 (Source: TIM Group’s historicals)

In April 2018, Cassa depositi e prestiti acquired 4.3% of Telecom Italia. Another 8.9% is held by Paul Singer through the Elliott fund, which, in the May 2018 shareholders' meeting, secured 49.8% of the votes, surpassing Vivendi at 47.2%. Despite being the largest shareholder with 23.9% of the share capital at the time, Vivendi was ousted.

From 2019, Telecom Italia is rebranded in Gruppo TIM.

From 2019, Telecom Italia is rebranded in Gruppo TIM.

Ownership structure as of November 2023 (Source: TIM Group website)

Deal rationale

While TIM explored the option of a sale as early as 2013, in the meantime, things only got worse for the European giant: Net debt skyrocketed, with net-debt-to-EBITDA ratio reaching 4.4x this year, their share price is currently less than half of what it was a decade ago and their market share has constantly gone down. And with current interest rates high and TIM bonds being rated as junk, TIM was forced to make a move.

KKR, on the other hand, found a cheap, indebted company where they might improve operations and turn a significant profit. They already have experience in the sector, and they find Europe’s highly fragmented market with over 100 companies operating in telecom an attractive sector: Vantage Towers, FiberCop and Telenor Fiber all being deals closed this decade. FiberCop, a partnership between KKR, TIM and FastWeb aims to accelerate Italy’s fiber development by connecting both residential and office space with fiber optic and proves the fund’s ambition to connect Italy.

Vivendi: the excluded party

Vivendi’s opposition

The recent decision by Telecom Italia (TIM) to accept a €22bn ($24bn) bid from U.S. private equity firm KKR for its network operations has ignited tensions with its major shareholder, Vivendi, leading to potential legal challenges. The opposition centers around several key concerns and objections. One of the primary reasons behind Vivendi's objection is the perceived undervaluation of TIM's network assets. Despite the bid from KKR potentially reaching €22bn, Vivendi argues that the separation of TIM's network assets is a strategic move that should have been subjected to a higher price tag. This disagreement on valuation has been a recurring theme throughout the negotiation process, with Vivendi expressing dissatisfaction with what it considers a low price for a crucial part of TIM's infrastructure. Vivendi contends that the sale of TIM's network assets represents a significant change in the company's corporate purpose. According to Vivendi, such a change requires a rewriting of the company bylaws, a process that necessitates consultation with shareholders. The objection is rooted in the belief that TIM should have sought shareholder approval before finalizing the deal. This argument is further supported by the claim that TIM has failed to apply specific provisions on material-related party transactions. Vivendi has not merely objected to presenting alternatives. The French conglomerate has proposed an alternative plan through London-based investment firm Merlyn Advisors, which TIM's board rejected, stating it is not in line with the delayering plan presented in July 2022. This rejection has led to further disagreement, with Vivendi asserting that the proposed sale does not align with the company's long-term strategy and could potentially harm TIM's financial sustainability.

Is the opposition justified?

Vivendi's objection and threat of legal action are rooted in its substantial stake in TIM, holding 23.75% of the company and over 17% of its voting rights. As a major shareholder, Vivendi certainly has the legal standing to challenge decisions that it deems detrimental to its interests and those of other shareholders. The heart of Vivendi's legal challenge lies in its interpretation of corporate governance rules. Vivendi argues that the sale of TIM's network assets necessitates a change in corporate purpose, which, according to its view, requires a shareholder vote. If Vivendi can successfully demonstrate that governance rules have been violated, it could strengthen its legal position against the board's decision. Vivendi's concerns about specific material-related party transactions, specifically TIM's alleged failure to apply relevant provisions, underscore its focus on regulatory compliance. If Vivendi can substantiate claims of non-compliance, it could further support its case for the unlawfulness of the board's decision. Vivendi may also argue that the sale of TIM's network assets, deemed of national strategic importance by the Italian government, requires a more thorough and transparent decision-making process. This argument may bolster Vivendi's claim that the board's decision should have involved a broader stakeholder discussion, aligning with the interests of both the company and the nation. Ultimately, Vivendi's opposition to the acquisition of TIM's network assets by KKR is multifaceted, touching upon valuation disputes, concerns about corporate purpose and governance rules, and strategic considerations. As a major shareholder, Vivendi has the legal standing to challenge the decision, particularly if it can demonstrate violations of governance rules and regulatory compliance. The unfolding legal battle will likely shed light on the extent of shareholder rights and the boundaries of corporate decision-making in a complex and strategic industry.

Exploring the Creation of a National Unified Network

The ongoing discourse surrounding the creation of a national unified network in Italy has been a long-debated topic. This complex discussion involves a diverse array of stakeholders, ranging from governmental bodies and regulatory authorities to network operators and other key players in the telecommunications landscape.

Potential merger with OpenFiber

In the year 2022, Telecom Italia (TIM) forged a significant commercial alliance with OpenFiber and FiberCop. This strategic partnership aimed at facilitating the repurposing of network infrastructures in areas commonly referred to as "white areas". These zones are characterized by a lack of broadband and ultra-wideband infrastructure, primarily due to the private operators' assessment that investing in these regions would not be financially viable. As part of this collaboration, TIM committed to providing its customers in these white areas with Open Fiber's optical fiber.

Open Fiber, functioning as a key player in the infrastructure landscape, assumed the responsibilities of designing, managing, and maintaining the fiber optic network. Leveraging Fiber-to-the-Home (FTTH) technology, Open Fiber achieved remarkable levels of efficiency and reliability in deploying cutting-edge connectivity solutions. It's worth noting that Open Fiber adopts a unique business model: it does not directly sell ultra-wideband network services to individuals, businesses, and public administration. Instead, it focuses on building and upgrading the entire fiber network and then leasing its use to partner companies.

Since December 2021, Open Fiber has operated under the direction and coordination of its sole shareholder, Open Fiber Holdings S.p.A. This entity is majority-owned, with a 60% stake held by CDP Equity S.p.A., a company affiliated with the Cassa Depositi e Prestiti Group (CDP). The remaining 40% ownership lies with Fibre Networks Holdings S.a.r.l., a company associated with the Macquarie group.

A notable detail is the role of CDP, holding just under 10% of TIM's shares and a substantial 60% ownership in Open Fiber. Due to this significant influence, CDP is categorized as a related party and is consequently restricted from exercising voting rights in certain matters.

In recent years, a significant discourse has unfolded surrounding the prospect of establishing a unified national network, driven by the pooling of assets belonging to Telecom Italia (TIM) and those developed by the expanding Open Fiber. The recent sale of NetCo by TIM to KKR has reignited considerations about the creation of a singular network operator for the entire Italian territory, under the control of CDP and with the participation of foreign funds.

The contemplation of selling the network has been a focal point of discussions for Telecom since 2013. Despite resistance from its major shareholder, Vivendi, this deal is perceived as the pivotal strategy to secure the network's future. Notably, it allows the company, currently burdened with a junk rating, to substantially reduce its debt from €26 billion to €14 billion. This strategic move has garnered the attention of rating agencies Fitch, S&P, and Moody's, prompting them to place the group under review for a potential rating upgrade this week. Labriola, Chief of Telecom Italia, emphasized, "This [deal] is not just a financial operation; it will finally allow us to invest both within our company and outside, which is pivotal amid the current transformation within our sector."

From a financial perspective, the indicative prudential value of the offer for the fixed network, set to be separated from its services, is estimated at €20 billion (equity plus debt). An additional €2 billion in earn-out is contingent on the realization of the potential "unified network" with Open Fiber. However, the initiation of this deal is contingent on the network's separation from Telecom, with the operational takeover by Netco expected in the second half of the coming year.

The European Antitrust Authority Concerns

The Ministry of Economy is poised to seek assurances from the Antitrust that the agreement with the U.S. fund does not raise concerns about anti-competitive practices, especially concerning the scope of the network to be separated. In accordance with Italian regulations, the Antitrust Authority is granted the power to legally challenge administrative acts, regulations, and measures of any public administration violating competition protection norms. If the Authority were to perceive improper advantages for TIM following this transaction, there could be consequences such as a different network scope and unforeseen market regulations, all scenarios impacting the operation's economy and even the price. The prospective merger with Open Fiber will also undergo scrutiny from the EU Antitrust, given that CDP and Macquarie are shareholders in both networks. The Treasury's control over CDP, adds complexity to the situation: the Italian Minister of Economy hinted at the potential involvement of CDP in the restructuring of TIM, taking into account the constraints imposed by the Antitrust. The entire process is anticipated to unfold over several months before resolving.

Conclusion

KKR was well aware of the complexity of a deal that has been on the table for almost a decade, but nonetheless the US-based fund has now moved a concrete step towards its closing. The opposition of TIM’s largest shareholder Vivendi and the careful eyes of Antitrust Authorities on the creation of an Italian unified network are only two of the hurdles that KKR will have to face in the next years. A question now arises: will one of the leaders of the PE landscape, with a track record of stellar IRRs and successful exits, turn the ownership of TIM’s most valuable assets in a successful investment story, or add its name to the list of investors that have failed in restoring the value of one of Italy’s most iconic companies?

By Andrea Cavenago, Sofia Rubino, Dinu Cionga, Elias Emery

SOURCES

- Financial Times

- Reuters

- Il Sole 24 Ore

- Tim company disclosures

- Vivendi company disclosures