On Wednesday, October 3rd 2018, Aston Martin went public, at a share price of £19 in its initial public offering on the London Stock Exchange. Though there was an initial rise to £19.15, shares actually reversed on the London debut, falling as low as £17.75 on the first day of dealing. These results are not entirely unexpected, given the overall uncertainty in the general economy; investors not only fear US tariffs on foreign cars but also the potential disruption that Brexit might cause for supply chains and markets. Nonetheless, the CEO of Aston Martin, Andy Palmer, isn’t too concerned about the risks of the general economy, and remains confident that the IPO will increase the luxury carmakers’ investment capacity in the long-run. But, can such an ambitious growth strategy truly achieve favourable market outcomes in the long-run, or will it backfire given current execution and market risks?

Through the implementation of the “Second-Century Plan” in 2015, Aston Martin has not only experienced recent revenue growth, but also an accelerating sales volume. In fact, as a result of the popularity of the DB11 and vantage models, which led to increasing sales, revenue rose nearly 48% from £593m in 2016 to £876m in 2017. The fundamental idea behind this long-term growth plan is to launch seven car models in seven years, one car every year from 2016 through to 2022, with each model having a seven-year lifecycle in hopes of establishing long-term immovability across the firm. If successful, this turnaround strategy would make Aston Martin the first luxury car producer to deliver a product within each division of the luxury car market, providing it with a competitive advantage that could even outrun its Italian competitor Ferrari. According to Palmer, this expansive and strengthening initiative will create a necessary momentum within the firm; this will not only increase stability, but will more importantly establish governance. This is where the IPO becomes very convenient; listing encourages firms to have independent shareholders and non-executive directors, and it is precisely such governance, which will allow the initial tempo to continue over many decades. Yet, the worry still remains whether Aston Martin will be able to justify the current valuation in the coming years, through the delivery of a highly ambitious plan, something that they have never been able to deliver before.

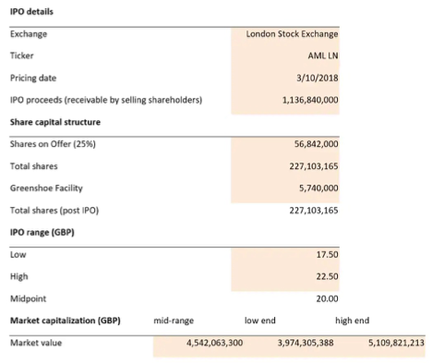

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the final listing price was actually set on the lower end of its IPO range. Thus, Aston Martin market value lies just above £4 billion, which is far lower than its initial valuation of over £5billion. Now, whilst this may be caused by the weakened London IPO market, it could also imply investor uncertainty about the perhaps overly ambitious valuation of the firm. Yet, Palmer denies these suppositions, confirming that the primary factor that pushed this price down was in fact the carmakers’ intention to obtain a high-quality book. They want investors that support Aston Martin’s long-term growth plan, and the only way they could attract such investors was by choosing a suitable share price.

Furthermore, the CEO seems convinced that the luxury firm is relatively shielded from these trade tensions and Brexit fears, given the industry that it is in. Luxury companies generally outlive these headwinds better than other firms given that their buyers are usually less price sensitive. In Palmer’s view, a possible EU tariff on British cars would mean that cars sold to Europe would become more expensive, however, other luxury cars would also become costlier in Europe and so the firm would actually become more competitive in its own market. In turn, a tariff would weaken the British pound, leading to cheaper exports and thus, higher profitability for Aston Martin. Overall, it appears as though external factors such as execution and market risks will not have a large impact on the firm’s outlook in the long-run.

This, however, reveals that the success of Aston Martin’s “Second Century Plan” relies heavily on the growing population of high net-worth individuals and their willingness to spend on luxury goods. With a compound annual growth rate of 7% of HNWI between 2010 and 2016, Aston Martin can fortunately expect promising growth prospects. In addition, the luxury cars division is also currently the fastest growing division in the luxury goods market, further suggesting that the IPO will leaven Aston Martin’s ability to achieve increased profit margins in the long-run.

Ultimately, Palmer’s optimism for the firms’ future is based on the success of its Italian rival Ferrari, which experienced a share increase of 160% since its New York IPO in 2016. Yet this is where the problem lies. Aston Martin’s image is not only weaker, but it also faces much smaller margins than Ferrari, and has a history of uneven sales and instable finances. In this way, the firm may be anticipating too large successes of its turnaround plan and the IPO, and thus, it is improbable that Aston Martin will be able to lift profitability levels similar to those that Ferrari has achieved.

Lilian Cohaus

Through the implementation of the “Second-Century Plan” in 2015, Aston Martin has not only experienced recent revenue growth, but also an accelerating sales volume. In fact, as a result of the popularity of the DB11 and vantage models, which led to increasing sales, revenue rose nearly 48% from £593m in 2016 to £876m in 2017. The fundamental idea behind this long-term growth plan is to launch seven car models in seven years, one car every year from 2016 through to 2022, with each model having a seven-year lifecycle in hopes of establishing long-term immovability across the firm. If successful, this turnaround strategy would make Aston Martin the first luxury car producer to deliver a product within each division of the luxury car market, providing it with a competitive advantage that could even outrun its Italian competitor Ferrari. According to Palmer, this expansive and strengthening initiative will create a necessary momentum within the firm; this will not only increase stability, but will more importantly establish governance. This is where the IPO becomes very convenient; listing encourages firms to have independent shareholders and non-executive directors, and it is precisely such governance, which will allow the initial tempo to continue over many decades. Yet, the worry still remains whether Aston Martin will be able to justify the current valuation in the coming years, through the delivery of a highly ambitious plan, something that they have never been able to deliver before.

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the final listing price was actually set on the lower end of its IPO range. Thus, Aston Martin market value lies just above £4 billion, which is far lower than its initial valuation of over £5billion. Now, whilst this may be caused by the weakened London IPO market, it could also imply investor uncertainty about the perhaps overly ambitious valuation of the firm. Yet, Palmer denies these suppositions, confirming that the primary factor that pushed this price down was in fact the carmakers’ intention to obtain a high-quality book. They want investors that support Aston Martin’s long-term growth plan, and the only way they could attract such investors was by choosing a suitable share price.

Furthermore, the CEO seems convinced that the luxury firm is relatively shielded from these trade tensions and Brexit fears, given the industry that it is in. Luxury companies generally outlive these headwinds better than other firms given that their buyers are usually less price sensitive. In Palmer’s view, a possible EU tariff on British cars would mean that cars sold to Europe would become more expensive, however, other luxury cars would also become costlier in Europe and so the firm would actually become more competitive in its own market. In turn, a tariff would weaken the British pound, leading to cheaper exports and thus, higher profitability for Aston Martin. Overall, it appears as though external factors such as execution and market risks will not have a large impact on the firm’s outlook in the long-run.

This, however, reveals that the success of Aston Martin’s “Second Century Plan” relies heavily on the growing population of high net-worth individuals and their willingness to spend on luxury goods. With a compound annual growth rate of 7% of HNWI between 2010 and 2016, Aston Martin can fortunately expect promising growth prospects. In addition, the luxury cars division is also currently the fastest growing division in the luxury goods market, further suggesting that the IPO will leaven Aston Martin’s ability to achieve increased profit margins in the long-run.

Ultimately, Palmer’s optimism for the firms’ future is based on the success of its Italian rival Ferrari, which experienced a share increase of 160% since its New York IPO in 2016. Yet this is where the problem lies. Aston Martin’s image is not only weaker, but it also faces much smaller margins than Ferrari, and has a history of uneven sales and instable finances. In this way, the firm may be anticipating too large successes of its turnaround plan and the IPO, and thus, it is improbable that Aston Martin will be able to lift profitability levels similar to those that Ferrari has achieved.

Lilian Cohaus