The origins of the Black Sea Grain Initiative

February 24th marks the date Russia initiated its invasion of Ukraine, a military operation that commenced as an escalation of the long-standing Russo-Ukrainian war which officially began in 2014. Among its many negative consequences, this conflict also generated a wide-spread food crisis, mainly affecting Asia and Africa. Many countries in these regions began to suffer from ‘acute hunger’, according to the UN, which estimated that an additional 47 million people could face starvation because of the war. The war accelerated an already rapid surge in world food prices, which were at record highs in February prior to the start of the war, with prices increasing more than 20% year-on-year following a disruption of the food supply chain due to COVID-19.

March showed a 40% increase in prices year-on-year, as the war compounded already existing issues with food production and distribution. This does not come as a surprise, since Russia and Ukraine are two of the world’s largest crop exporters. When the war started, Ukraine exported 10% of wheat globally, it was the largest exporter of sunflower oil and the fourth- largest exporter of corn in the world. Combined, these two nations are responsible for the production of 53% of sunflower seeds, 27% of wheat in the world and produce almost 10% of all calories traded globally. In the first few weeks of the war, Russia was quick to seize Ukraine’s most important ports, halting all its shipments into the Black Sea and aggravating an already precarious situation in world food markets.

The following months demonstrated the severity of the situation, with the head of the World Food Program warning that the crisis could escalate to levels we had never seen before. However, after months of negotiations between the UN, Russia, Ukraine and Turkey, a deal was signed to allow Ukraine to resume its grain shipments, in order to address the world food crisis. The Black Sea Grain Initiative, is a 120-day deal that guarantees safe navigation in the Black Sea of ships carrying grain, fertilizer and other foodstuffs. All the ships have to travel through predetermined corridors and cross through Istanbul, Turkey for inspection. The deal, characterized as a “Beacon of hope” by the UN secretary-general, restored prices back to pre- war levels and has allowed millions of tonnes of cargo to be shipped into Europe, Asia and Africa.

From the 3rd of August, the day the first shipment of 26,000 tonnes of Ukrainian food was allowed into the Black Sea, more than 12,000,000 tonnes of cargo have been shipped as a result of the deal. If its ports operate well, Ukraine has declared its intent to export 60mn tonnes of grains and related foodstuffs over the nine months following the approval of the initiative. Shipments mainly consist of corn (41%), wheat (29%), and oil crops such as rapeseed (7%) or sunflower (6%), and are primarily directed to Spain (1.8mn tonnes), Turkey (1.6mn tonnes) and China (1.5mn tonnes). Countries in South Asia and the Middle East have also received substantial support from the deal, with more than 1.5mn tonnes being directed to these regions.

The agreement was initially valid for 120 days and was set to expire on November 19th unless renewed. The weeks prior to the expiration date were full of uncertainty, as Russia declared on October 29th its suspension of the deal, following proclaimed Ukrainian drone attacks on Russian ships safeguarding the Black Sea safe corridor. Only 4 days later, Russia agreed to resume the deal after the UN and Turkey intervened to alleviate the conflict. There was no talk about the extension of the deal until November 17th, 2 days prior to its expiration, when the UN secretary-general announced the renewal of the deal for another 120 days. Going forward, the sustenance and extension of the deal remain unclear, as the evolution of the Russia-Ukraine war is extremely unpredictable. The following months could see a complete resolution of the conflict and a return to normality, or a full-blown food crisis as two of the world’s largest foodstuff exporters are isolated from the rest of the world.

The deal scope and the interests of Asian countries

The extension of the deal is bound to have a stabilising effect on the global economy and partially alleviate the food crisis the world is facing – indeed, after its announcement, food price indices worldwide recorded a slight drop. However, the uncertainty around its continuity revealed several vulnerabilities within certain prominent Asian economies. Speculations around the suspension of the deal suggested that it would lead to significant increases in the price of essential foodstuffs and fertilisers, particularly exacerbating the effect of inflation in Asian countries since as aforementioned Ukraine and Russia are major exporters of these products. Russia’s annual fertiliser exports total in excess of 50mn tonnes, or 13% of global values, and the majority of this sum goes to Asian countries; a suspension of the deal would have directly impaired many countries’ ability to produce food domestically at all, as crop yields immediately drop when the use of synthetic fertiliser is interrupted.

However, Russia’s rationale for accepting to renew the deal partially focused on the fact that it would be an act of service to developing countries. Since it first began, exports have been focused on addressing the food crisis in Africa, which has broader humanitarian implications. In what concerns Asia, the continent had received 40 shipments by early November, of which 21 went to China, supplying it with 990,000 tonnes of corn, sunflower meal, sunflower oil, and barley. Bangladesh received 268,000 tonnes of wheat, and India received seven sunflower oil cargoes. South Korea received 198,700 tonnes of corn shipments, Vietnam 116,00 tonnes of wheat, and Malaysia 4,000 tonnes of sunflower oil. The single largest shipment amounted to 71,500 tonnes of wheat, delivered to Indonesia. Around two-thirds of the total shipments went to developed, Western European nations; this is a point underlined by Vladimir Putin, who accuses the West of “robbing” developing nations. Analysts disagree about the relevance of this detail.Some argue that, overall, irrespective of the destination of the shipments, global food prices will fall on average. On the flip side, this could lead to broadening disparities and inequalities, as wealthy nations are cushioned from the full effects of this crisis while consumers elsewhere face growing prices. In this complex scenario, the vulnerability of Asian countries also varies depending on how reliant local economies are on the extension of the deal.

China and Japan - two major importers with significant stakes at play

Russia and China are major import-export partners. In 2021, exports to China accounted for 9.8% of Russia’s total grain exports, so we would expect it to be hit very hard. However, China and Russia have a special diplomatic relationship, which has enabled it to lift all import restrictions on wheat from Russia. Additionally, China currently holds the world’s greatest wheat stocks – 51% of total global wheat stocks that increases the sufficiency of the country and slightly limit the risks associated to a suspension of the deal. Another important player in the Asia-Pacific area that is deeply interested by the deal is Japan. The country is also very reliant on imported food from Russia, with certain provinces, such as Hokkaido, sourcing virtually all seafood from Russia – 97.4% of its sea urchin, 84.1% of its crab, 51.1% of its salmon, and 38.8% of its squid. Government estimates put Japan’s self-sufficiency rate at just around 37%, meaning that the vast majority of its consumption comes from imported products: grains and seafood alike. Russia is a major trading partner in both fields. In Japan, wheat resale prices jumped by 17% in the early days of the war. Furthermore, shortages in oil have greatly increased the demand for corn as a source of ethanol, a crude oil substitute, which only reinforces food insufficiencies. Japan is known to be one of the most imported energy reliant countries in the APAC region, and inflation in the last year has also been driven up by growing energy prices - Russia supplied 9% of Japan’s LNG, 4% of crude oil, and 13% of coal. This data highlights the importance of the deal for the Japanese economy that could resent a lot from the current geopolitical tensions.

China and Japan are not the only countries to be involved in this alarming scenario, but as shown by the data regarding the amount of supplies interested in the deal, all the Asian economies will be heavily hit by a suspension of the deal. Researchers Genevieve Donellon- May and Paul Teng make the following predictions for consumers in the Asia-Pacific: “it’s going to get worse [...] with countries impacted by higher [priced] fertilizer, fuel, and food prices, further exacerbating Covid-related disruptions to the supply chains and climate change-induced extreme weather events, which have impacted agricultural production and food security”. The already disrupted scenario mentioned by the researchers ultimately obliged Central Banks to find a solution against the high levels of inflation, with some countries that implemented stronger policies than others. In light of this, some Asian economies may face more challenges from the suspension of the deal with their Central Banks that may not be able to respond with the adequate monetary policies to counter the macroeconomic consequences of such an event.

Macroeconomic scenario and effects of a potential suspension of the deal

The risks that a possible suspension of the deal could have on Asian economies cause no small amount of concern. With Asian economies in an extremely complex situation due to the high elasticity of inflation to grain prices, the scenario demonstrates the fragility of their equilibria due to high dependency from imports. Although countries like China have a strong and credible central bank as an insurer of the economy, the recessionary environment is indirectly limiting potential inflationary pressures. On the other side of the coin, the extremely high dependency of Pakistan and Indonesia on Ukrainian and Russian grains put a serious threat to those countries’ central banks that already are in the position to adopt prohibitively restrictive monetary policies while incapable of acting on weak currencies. Within the APAC area, the deal represents a major threat particularly to China, Indonesia and Pakistan.

China – rising reliance on imports

Against a backdrop of China with an inflation rate at 2.1%, the potential easing of zero covid policy and the disbursement of significant credit stimulus to support an already reeling real estate market could lead to an exacerbation of the inflation rate for the socialist republic. With a growth in corn and wheat imports of 490% and 180% respectively compared to 2019 data, China has been increasingly dependent on countries such as Ukraine and Russia in terms of agricultural commodities. The reasons for this increase are to be found in the many supply chain issues and the zero-covid policy that Xi Jinping is pursuing.

China is the first world producer of meat with 88,156,000 tonnes per year, but the reliance of the former on Ukrainian grain imports is becoming more and more vital for its economy, with the increase in prices further reducing companies' margins, which then try to transfer the bargain of higher costs to consumers. A possible inflationary scenario in China would lead to possible monetary policy intervention by the People Bank of China, which, with interest rates already at 3.65%, may find itself forced to raise them further to avoid overheating the economy.

February 24th marks the date Russia initiated its invasion of Ukraine, a military operation that commenced as an escalation of the long-standing Russo-Ukrainian war which officially began in 2014. Among its many negative consequences, this conflict also generated a wide-spread food crisis, mainly affecting Asia and Africa. Many countries in these regions began to suffer from ‘acute hunger’, according to the UN, which estimated that an additional 47 million people could face starvation because of the war. The war accelerated an already rapid surge in world food prices, which were at record highs in February prior to the start of the war, with prices increasing more than 20% year-on-year following a disruption of the food supply chain due to COVID-19.

March showed a 40% increase in prices year-on-year, as the war compounded already existing issues with food production and distribution. This does not come as a surprise, since Russia and Ukraine are two of the world’s largest crop exporters. When the war started, Ukraine exported 10% of wheat globally, it was the largest exporter of sunflower oil and the fourth- largest exporter of corn in the world. Combined, these two nations are responsible for the production of 53% of sunflower seeds, 27% of wheat in the world and produce almost 10% of all calories traded globally. In the first few weeks of the war, Russia was quick to seize Ukraine’s most important ports, halting all its shipments into the Black Sea and aggravating an already precarious situation in world food markets.

The following months demonstrated the severity of the situation, with the head of the World Food Program warning that the crisis could escalate to levels we had never seen before. However, after months of negotiations between the UN, Russia, Ukraine and Turkey, a deal was signed to allow Ukraine to resume its grain shipments, in order to address the world food crisis. The Black Sea Grain Initiative, is a 120-day deal that guarantees safe navigation in the Black Sea of ships carrying grain, fertilizer and other foodstuffs. All the ships have to travel through predetermined corridors and cross through Istanbul, Turkey for inspection. The deal, characterized as a “Beacon of hope” by the UN secretary-general, restored prices back to pre- war levels and has allowed millions of tonnes of cargo to be shipped into Europe, Asia and Africa.

From the 3rd of August, the day the first shipment of 26,000 tonnes of Ukrainian food was allowed into the Black Sea, more than 12,000,000 tonnes of cargo have been shipped as a result of the deal. If its ports operate well, Ukraine has declared its intent to export 60mn tonnes of grains and related foodstuffs over the nine months following the approval of the initiative. Shipments mainly consist of corn (41%), wheat (29%), and oil crops such as rapeseed (7%) or sunflower (6%), and are primarily directed to Spain (1.8mn tonnes), Turkey (1.6mn tonnes) and China (1.5mn tonnes). Countries in South Asia and the Middle East have also received substantial support from the deal, with more than 1.5mn tonnes being directed to these regions.

The agreement was initially valid for 120 days and was set to expire on November 19th unless renewed. The weeks prior to the expiration date were full of uncertainty, as Russia declared on October 29th its suspension of the deal, following proclaimed Ukrainian drone attacks on Russian ships safeguarding the Black Sea safe corridor. Only 4 days later, Russia agreed to resume the deal after the UN and Turkey intervened to alleviate the conflict. There was no talk about the extension of the deal until November 17th, 2 days prior to its expiration, when the UN secretary-general announced the renewal of the deal for another 120 days. Going forward, the sustenance and extension of the deal remain unclear, as the evolution of the Russia-Ukraine war is extremely unpredictable. The following months could see a complete resolution of the conflict and a return to normality, or a full-blown food crisis as two of the world’s largest foodstuff exporters are isolated from the rest of the world.

The deal scope and the interests of Asian countries

The extension of the deal is bound to have a stabilising effect on the global economy and partially alleviate the food crisis the world is facing – indeed, after its announcement, food price indices worldwide recorded a slight drop. However, the uncertainty around its continuity revealed several vulnerabilities within certain prominent Asian economies. Speculations around the suspension of the deal suggested that it would lead to significant increases in the price of essential foodstuffs and fertilisers, particularly exacerbating the effect of inflation in Asian countries since as aforementioned Ukraine and Russia are major exporters of these products. Russia’s annual fertiliser exports total in excess of 50mn tonnes, or 13% of global values, and the majority of this sum goes to Asian countries; a suspension of the deal would have directly impaired many countries’ ability to produce food domestically at all, as crop yields immediately drop when the use of synthetic fertiliser is interrupted.

However, Russia’s rationale for accepting to renew the deal partially focused on the fact that it would be an act of service to developing countries. Since it first began, exports have been focused on addressing the food crisis in Africa, which has broader humanitarian implications. In what concerns Asia, the continent had received 40 shipments by early November, of which 21 went to China, supplying it with 990,000 tonnes of corn, sunflower meal, sunflower oil, and barley. Bangladesh received 268,000 tonnes of wheat, and India received seven sunflower oil cargoes. South Korea received 198,700 tonnes of corn shipments, Vietnam 116,00 tonnes of wheat, and Malaysia 4,000 tonnes of sunflower oil. The single largest shipment amounted to 71,500 tonnes of wheat, delivered to Indonesia. Around two-thirds of the total shipments went to developed, Western European nations; this is a point underlined by Vladimir Putin, who accuses the West of “robbing” developing nations. Analysts disagree about the relevance of this detail.Some argue that, overall, irrespective of the destination of the shipments, global food prices will fall on average. On the flip side, this could lead to broadening disparities and inequalities, as wealthy nations are cushioned from the full effects of this crisis while consumers elsewhere face growing prices. In this complex scenario, the vulnerability of Asian countries also varies depending on how reliant local economies are on the extension of the deal.

China and Japan - two major importers with significant stakes at play

Russia and China are major import-export partners. In 2021, exports to China accounted for 9.8% of Russia’s total grain exports, so we would expect it to be hit very hard. However, China and Russia have a special diplomatic relationship, which has enabled it to lift all import restrictions on wheat from Russia. Additionally, China currently holds the world’s greatest wheat stocks – 51% of total global wheat stocks that increases the sufficiency of the country and slightly limit the risks associated to a suspension of the deal. Another important player in the Asia-Pacific area that is deeply interested by the deal is Japan. The country is also very reliant on imported food from Russia, with certain provinces, such as Hokkaido, sourcing virtually all seafood from Russia – 97.4% of its sea urchin, 84.1% of its crab, 51.1% of its salmon, and 38.8% of its squid. Government estimates put Japan’s self-sufficiency rate at just around 37%, meaning that the vast majority of its consumption comes from imported products: grains and seafood alike. Russia is a major trading partner in both fields. In Japan, wheat resale prices jumped by 17% in the early days of the war. Furthermore, shortages in oil have greatly increased the demand for corn as a source of ethanol, a crude oil substitute, which only reinforces food insufficiencies. Japan is known to be one of the most imported energy reliant countries in the APAC region, and inflation in the last year has also been driven up by growing energy prices - Russia supplied 9% of Japan’s LNG, 4% of crude oil, and 13% of coal. This data highlights the importance of the deal for the Japanese economy that could resent a lot from the current geopolitical tensions.

China and Japan are not the only countries to be involved in this alarming scenario, but as shown by the data regarding the amount of supplies interested in the deal, all the Asian economies will be heavily hit by a suspension of the deal. Researchers Genevieve Donellon- May and Paul Teng make the following predictions for consumers in the Asia-Pacific: “it’s going to get worse [...] with countries impacted by higher [priced] fertilizer, fuel, and food prices, further exacerbating Covid-related disruptions to the supply chains and climate change-induced extreme weather events, which have impacted agricultural production and food security”. The already disrupted scenario mentioned by the researchers ultimately obliged Central Banks to find a solution against the high levels of inflation, with some countries that implemented stronger policies than others. In light of this, some Asian economies may face more challenges from the suspension of the deal with their Central Banks that may not be able to respond with the adequate monetary policies to counter the macroeconomic consequences of such an event.

Macroeconomic scenario and effects of a potential suspension of the deal

The risks that a possible suspension of the deal could have on Asian economies cause no small amount of concern. With Asian economies in an extremely complex situation due to the high elasticity of inflation to grain prices, the scenario demonstrates the fragility of their equilibria due to high dependency from imports. Although countries like China have a strong and credible central bank as an insurer of the economy, the recessionary environment is indirectly limiting potential inflationary pressures. On the other side of the coin, the extremely high dependency of Pakistan and Indonesia on Ukrainian and Russian grains put a serious threat to those countries’ central banks that already are in the position to adopt prohibitively restrictive monetary policies while incapable of acting on weak currencies. Within the APAC area, the deal represents a major threat particularly to China, Indonesia and Pakistan.

China – rising reliance on imports

Against a backdrop of China with an inflation rate at 2.1%, the potential easing of zero covid policy and the disbursement of significant credit stimulus to support an already reeling real estate market could lead to an exacerbation of the inflation rate for the socialist republic. With a growth in corn and wheat imports of 490% and 180% respectively compared to 2019 data, China has been increasingly dependent on countries such as Ukraine and Russia in terms of agricultural commodities. The reasons for this increase are to be found in the many supply chain issues and the zero-covid policy that Xi Jinping is pursuing.

China is the first world producer of meat with 88,156,000 tonnes per year, but the reliance of the former on Ukrainian grain imports is becoming more and more vital for its economy, with the increase in prices further reducing companies' margins, which then try to transfer the bargain of higher costs to consumers. A possible inflationary scenario in China would lead to possible monetary policy intervention by the People Bank of China, which, with interest rates already at 3.65%, may find itself forced to raise them further to avoid overheating the economy.

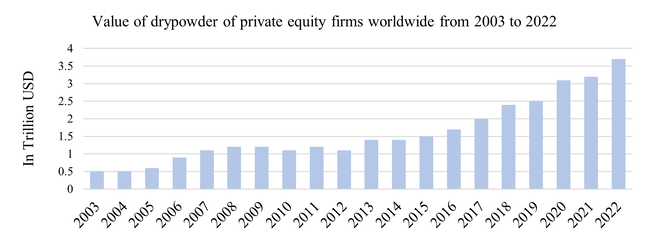

Source: Statista

Indonesia – an uncertain future ahead

One of the most potentially damaged economies by the suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative is Indonesia. With a population of 275mn, Indonesia is the 4th largest importer of grains from Ukraine with over 750mn tonnes in 2021. From an economic perspective, Indonesia’s economy expanded 5.75% from a year earlier in the third quarter (the fastest pace in over a year) and the subsequent increase of inflation rate to 5.95% pushed the Bank of Indonesia to intervene increasing the reverse-repo rates to 5.25%. By digging deep in the components of the Indonesia’s CPI it’s visible how Food and Food providers are weighted on the overall index, representing 25% and 8.7% respectively. The consequences that Black Sea Grain Initiative could have on Indonesian economy are uncertain, with a weak currency (worth mentioning that the Indonesian Rupiah equivalent of 1 dollar is 15,690.00 IDR) and a relatively credible Central Bank, Indonesia’s inflationary response could potentially be amplified and less “controllable”.

One of the most potentially damaged economies by the suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative is Indonesia. With a population of 275mn, Indonesia is the 4th largest importer of grains from Ukraine with over 750mn tonnes in 2021. From an economic perspective, Indonesia’s economy expanded 5.75% from a year earlier in the third quarter (the fastest pace in over a year) and the subsequent increase of inflation rate to 5.95% pushed the Bank of Indonesia to intervene increasing the reverse-repo rates to 5.25%. By digging deep in the components of the Indonesia’s CPI it’s visible how Food and Food providers are weighted on the overall index, representing 25% and 8.7% respectively. The consequences that Black Sea Grain Initiative could have on Indonesian economy are uncertain, with a weak currency (worth mentioning that the Indonesian Rupiah equivalent of 1 dollar is 15,690.00 IDR) and a relatively credible Central Bank, Indonesia’s inflationary response could potentially be amplified and less “controllable”.

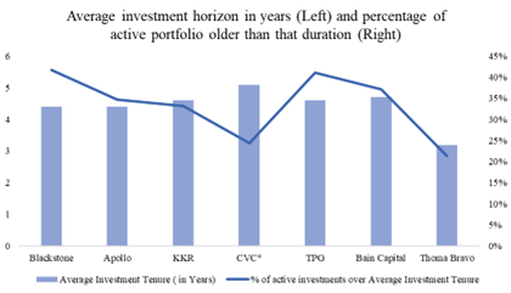

Source: Bloomberg

Pakistan – economic stability at risk

For Pakistan, the Ukraine-Russia conflicts and the subsequent increase in agricultural commodities made the situation worse again. The cause for this has to be researched in the disruptions in the supply chain given that Ukraine represents the largest wheat supplier to Pakistan, exporting over 1.2 megatonnes of wheat in 2021. Despite the Black Sea grain initiative has given agricultural commodities prices further room to decrease, however, the concerns for Pakistan remain very serious.

CPI inflation in November was 26.6% from 23.2% in the previous month, with the main pressure coming from utilities and food. The depreciation of the Rupee has led to an increase of inflation due to imported goods: the former has in fact fallen by 23% against the dollar in August 2022, further worsening the national account situation since the share of total imports represented by oil (purchased in USD) is still about 26-30%. Finally, one of the main reasons for the high inflation level is the lag effect of the large budget deficit during the previous year, this latter was in fact 9% of the national GDP in the last 12 months. But what was the reaction of the central bank to such disruptions? From a monetary perspective, Pakistan’s central bank raised its key policy rate to 16% to ensure high inflation does not get entrenched. Given the high dependency of the country on Ukrainian and Russian wheat and corn imports, the Black Sea Grain Initiative represents now more than ever a crucial factor for the economic stability of more than 225 million people in Pakistan.

Overall, the Asia Pacific region is projected to drive wheat consumption for several reasons: the consumer preferences are shifting more and more toward a grain-based diet, wheat is becoming more and more deployed in animal feed and lastly, the growth in population is pushing governments to ensure food security in the foreseeable future. Overall, China, representing the country with the highest increase in grain imports, is locked between continuous lockdowns and a significant slowdown of the economy due to a major disruption in the real estate sector, with a central bank enacting a relatively accommodative monetary policy in order to keep inflation levels at acceptable levels. On the other side, countries like Indonesia and Pakistan present very similar traits both in terms of aggregate demand of agricultural commodities and in terms of macroeconomic situation. With large shares of consumption baskets depending on food and energy prices, these countries have been seeing double digits inflation for months, which jeopardizes their economic growth outlook. Global wheat markets continue to face turbulence, with Russia’s continuous threats of retaliation against Western economies suggesting a potential suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative.

For Pakistan, the Ukraine-Russia conflicts and the subsequent increase in agricultural commodities made the situation worse again. The cause for this has to be researched in the disruptions in the supply chain given that Ukraine represents the largest wheat supplier to Pakistan, exporting over 1.2 megatonnes of wheat in 2021. Despite the Black Sea grain initiative has given agricultural commodities prices further room to decrease, however, the concerns for Pakistan remain very serious.

CPI inflation in November was 26.6% from 23.2% in the previous month, with the main pressure coming from utilities and food. The depreciation of the Rupee has led to an increase of inflation due to imported goods: the former has in fact fallen by 23% against the dollar in August 2022, further worsening the national account situation since the share of total imports represented by oil (purchased in USD) is still about 26-30%. Finally, one of the main reasons for the high inflation level is the lag effect of the large budget deficit during the previous year, this latter was in fact 9% of the national GDP in the last 12 months. But what was the reaction of the central bank to such disruptions? From a monetary perspective, Pakistan’s central bank raised its key policy rate to 16% to ensure high inflation does not get entrenched. Given the high dependency of the country on Ukrainian and Russian wheat and corn imports, the Black Sea Grain Initiative represents now more than ever a crucial factor for the economic stability of more than 225 million people in Pakistan.

Overall, the Asia Pacific region is projected to drive wheat consumption for several reasons: the consumer preferences are shifting more and more toward a grain-based diet, wheat is becoming more and more deployed in animal feed and lastly, the growth in population is pushing governments to ensure food security in the foreseeable future. Overall, China, representing the country with the highest increase in grain imports, is locked between continuous lockdowns and a significant slowdown of the economy due to a major disruption in the real estate sector, with a central bank enacting a relatively accommodative monetary policy in order to keep inflation levels at acceptable levels. On the other side, countries like Indonesia and Pakistan present very similar traits both in terms of aggregate demand of agricultural commodities and in terms of macroeconomic situation. With large shares of consumption baskets depending on food and energy prices, these countries have been seeing double digits inflation for months, which jeopardizes their economic growth outlook. Global wheat markets continue to face turbulence, with Russia’s continuous threats of retaliation against Western economies suggesting a potential suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative.

Source: Bloomberg

Potential solutions for Asian Countries to decrease their exposure to the uncertainty of the deal

Despite the numerous concerns about major increases in prices of agricultural commodities in Asia Pacific regions, there are solutions that could potentially limit those upward pressures. In what concerns Australia, because of the hole left behind in the APAC area by Russia and Ukraine, Australian wheat exports are expected to reach around $12bn in value, with this coming year recording the second-highest production level in its history. As a result, Australia issupplying most of Indonesia’s wheat needs, among others. It is also supplying 26% of global barley exports. India is also emerging as an alternative wheat market, currently making up 5% of the world’s exports, a figure that is set to grow as rising import costs force countries to look inward. In this sense, Asian countries are taking measures to increase food security and internalize agricultural production. In Thailand, South Korea, and the Philippines, buy tenders for feed wheat were issued, aiming to increase the transparency, the security for sellers, and to support the purchase of wheat domestically. The Chinese and Japanese governments have adopted or are in the process of adopting resolutions to strengthen domestic production. Malaysia is imposing price controls and issuing grants to consumers to slow down price growth. For instance, the price of poultry has been capped at the equivalent of $2.10/kg. An $80mn subsidy has been set aside by the government to enable this. India is taking a different approach, choosing instead to remove the customs duty on edible oils and imposing export bans for similar essential food products.

However, if on the one side the hopes for China to reach an auto sufficiency target in terms of grain production are ambitious, on the other it demonstrated not to be able to sustain such a goal. With a recessionary environment due to the recent real estate crisis and the significant slowdown in the supply chain, China had been forced to outsource larger and larger amounts of grains with a stunning 65.5mn metric tonnes of cereal grains and flower imported compared to 17.5 in 2019, part of which was used to increase the strategic reserves in order for the socialist republic to face further potential pandemic outbreaks.

While Pakistan had set a goal of producing 27mn tonnes of wheat domestically in 2022, due to a number of reasons, including water scarcity and the redevelopment of agricultural land, scientists were already predicting its harvests would be slashed by 15 percent forcing the country to further increase its imports of grains. In an already deteriorated social and economic environment and with further inflationary pressure, in the case of a suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, could potentially lead to mass starvation of 225mn Pakistani people, finally forcing the government to an intervention that would inevitably damage the national balance of payments.

Conclusion

The uncertainty around the extension of the deal pushes Asian countries to steer their economies towards domestic production. Although they are currently screening potential solutions to decrease their reliance on Ukraine and Russia, their efforts may likely not bring a tangible solution in the foreseeable future. This implies that, at the current state of affairs, a suspension would heavily affect the Asian economies leading to a response of Central Banks that, however, are already applying strict monetary policies to contrast inflation.

Although it is uncertain how the situation will evolve and whether the deal will cause tangible problems, it is worth highlighting its importance and its capacity to further disrupt struggling economies.

While we do our reflections on the possible dynamics that the cancellation of the Black Sea Grain Initiative would bring, could we possibly be facing a major shift in the medium-run economic cycle of the Asian economies?

By Deivi Harmzaraj, Giorgio Gusella, and Georgia-Alesia Mirica

Sources:

Despite the numerous concerns about major increases in prices of agricultural commodities in Asia Pacific regions, there are solutions that could potentially limit those upward pressures. In what concerns Australia, because of the hole left behind in the APAC area by Russia and Ukraine, Australian wheat exports are expected to reach around $12bn in value, with this coming year recording the second-highest production level in its history. As a result, Australia issupplying most of Indonesia’s wheat needs, among others. It is also supplying 26% of global barley exports. India is also emerging as an alternative wheat market, currently making up 5% of the world’s exports, a figure that is set to grow as rising import costs force countries to look inward. In this sense, Asian countries are taking measures to increase food security and internalize agricultural production. In Thailand, South Korea, and the Philippines, buy tenders for feed wheat were issued, aiming to increase the transparency, the security for sellers, and to support the purchase of wheat domestically. The Chinese and Japanese governments have adopted or are in the process of adopting resolutions to strengthen domestic production. Malaysia is imposing price controls and issuing grants to consumers to slow down price growth. For instance, the price of poultry has been capped at the equivalent of $2.10/kg. An $80mn subsidy has been set aside by the government to enable this. India is taking a different approach, choosing instead to remove the customs duty on edible oils and imposing export bans for similar essential food products.

However, if on the one side the hopes for China to reach an auto sufficiency target in terms of grain production are ambitious, on the other it demonstrated not to be able to sustain such a goal. With a recessionary environment due to the recent real estate crisis and the significant slowdown in the supply chain, China had been forced to outsource larger and larger amounts of grains with a stunning 65.5mn metric tonnes of cereal grains and flower imported compared to 17.5 in 2019, part of which was used to increase the strategic reserves in order for the socialist republic to face further potential pandemic outbreaks.

While Pakistan had set a goal of producing 27mn tonnes of wheat domestically in 2022, due to a number of reasons, including water scarcity and the redevelopment of agricultural land, scientists were already predicting its harvests would be slashed by 15 percent forcing the country to further increase its imports of grains. In an already deteriorated social and economic environment and with further inflationary pressure, in the case of a suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, could potentially lead to mass starvation of 225mn Pakistani people, finally forcing the government to an intervention that would inevitably damage the national balance of payments.

Conclusion

The uncertainty around the extension of the deal pushes Asian countries to steer their economies towards domestic production. Although they are currently screening potential solutions to decrease their reliance on Ukraine and Russia, their efforts may likely not bring a tangible solution in the foreseeable future. This implies that, at the current state of affairs, a suspension would heavily affect the Asian economies leading to a response of Central Banks that, however, are already applying strict monetary policies to contrast inflation.

Although it is uncertain how the situation will evolve and whether the deal will cause tangible problems, it is worth highlighting its importance and its capacity to further disrupt struggling economies.

While we do our reflections on the possible dynamics that the cancellation of the Black Sea Grain Initiative would bring, could we possibly be facing a major shift in the medium-run economic cycle of the Asian economies?

By Deivi Harmzaraj, Giorgio Gusella, and Georgia-Alesia Mirica

Sources:

- Bloomberg

- Reuters

- Financial Times

- New York Times

- Asia Times

- TechWire Asia

- CSIS

- CNBC