What is a SPAC?

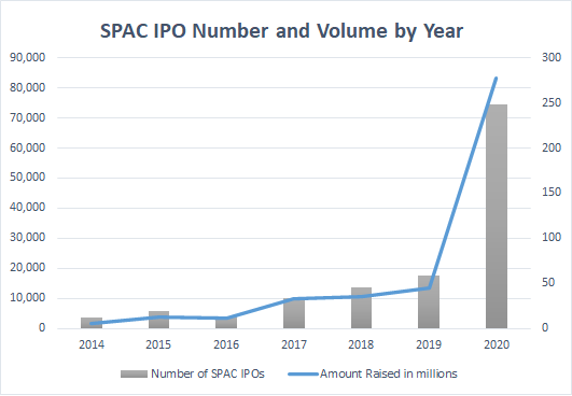

Special-Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) were created in 1993 but did not become significant until recently. In 2019 there were 59 SPAC IPOs, raising over $12 billion. However, in 2020 there were more than four times as many SPAC IPOs, raising over $75 billion. A SPAC is an alternative to an IPO, or a reverse takeover (less common) and it is essentially a new route to access the capital markets. It is set up by a sponsor, who is responsible for raising a blank check from investors. The structure of a SPAC is such that it democratizes public offerings by allowing non accredited investors to invest alongside the sponsors, thus providing investors with opportunities they might otherwise have missed. For instance, in one of the highest profile IPOs in 2020, Airbnb stock opened the first day of trading at a price that was two times greater than the price set at the IPO. However, had the company gone public through a SPAC, it would have given the public the opportunity to buy at a small premium to the acquisition price.

At the same time, the SPAC may also be beneficial to the company going public, since it provides with superior price discovery, given that the price is not set by the projections of the bankers, but rather by competing sponsors. A SPAC transaction is usually less cumbersome for the company, to the extent that they are prepared for a public offering. There is much less scrutiny by auditors, or regulating bodies such as the SEC, therefore a SPAC transaction may allow the company to go public months before it would if they were doing an IPO. Furthermore, the management would be allowed (and encouraged) to focus on running the business, since this would be in the best interests of the sponsors. The company also has the added benefit of receiving an approval stamp from respected long-term investors. Despite having similar underwriting fees, SPACs are also cheaper for the company due to lower direct expenses and indirect costs. The company management is also commonly allured by higher liquidity, since there is no lock-up period in a SPAC transaction.

In 2020, some of the best-known investors in the world raised or invested in SPACs, such as Apollo, Third Point, Pershing Square, or Coatue. Sponsoring a SPAC is particularly enticing to investors, since they typically retain 20% of the shares in the newly formed company. Thus, it is reasonable to project that, barring a stock market crash, SPACs should continue increasing in volume. To put it in perspective, even top investors such as Bill Ackman have stopped charging a 2 and 20 fee in their funds. Here, instead, a sponsor that makes a 10-billion-dollar acquisition could immediately receive $2 billion in revenues. However, that dilution comes at a cost to those investing alongside sponsors, since they must believe that the sponsor can turn every 1 dollar into 2.5 over a period of 7 years (assuming a 10% hurdle rate). Thus, investors should look for SPACs where the sponsor’s incentives are aligned with their own, as opposed to asset gatherers. Furthermore, investors must beware that there might not be a sufficient supply of high-quality companies given the growing number of SPACs seeking a target.

The rise of SPACs

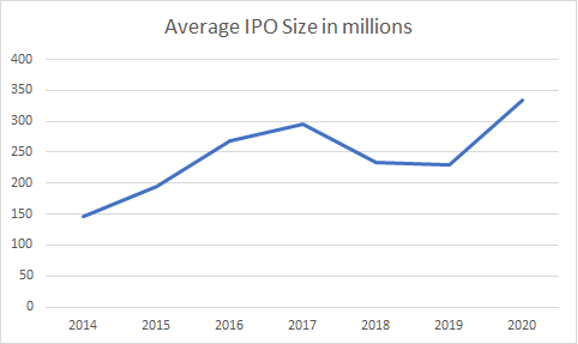

In the early 1990s, SPACs only played a small role within niche industries such as tech and commodities, as they provided private companies with the necessary growth capital at a faster pace during economic downturns. Blank check companies, however, were widely mistrusted by institutional and retail investors alike due to a combination of inadequate SEC regulation, in addition to unconstrained practices in the 1980s. These resulted in less prepared private companies joining the public market and displaying a weak track record in comparison to larger companies that would undergo a traditional IPO, thus damaging the reputation of their respective SPAC. As a result, the average SPAC would raise no more than $100 million, in comparison to today’s average of almost $400 million.

With the growth of private equity funds in the early 2000s and the proceeding legitimisation of SPACs by investment banks, their popularity began to rise. What followed were a series of SEC measures undertaken to protect investors, which increased transparency and removed listing fees in relation to the issuance of additional shares. During the 2008 financial crisis, distrust of markets became the norm, so the sole US SPAC IPO only raised a mere $36 million. By 2017, however, this distrust had slowly dissipated, and the first SPAC was listed in the NYSE. Now, the exchange reported over 50 individual SPACs in less than 5 years, which are responsible for the NYSE’s top listing volume in 2020. Due to the smaller size of early SPACs, most avoided large stock exchanges considering high transaction fees, but the increased visibility to recent investors now became an attractive feature to SPAC managers. Additionally, bulge bracket banks such as Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse have lifted restrictions against SPACs over the past 5 years and have consequently started their own.

Another key cause of the increase in popularity of SPACs over the past decade was the improvement in the calibre of companies choosing this method over a traditional IPO. Some critics argued that early-stage companies with less funding possibilities harmed the overall reputation of SPACs, as they would often underperform in the long-run. Virgin Galactic’s SPAC IPO in 2019, for example, raised questions regarding how appropriate it is to take a company public, if it is unprepared to meet cost obligations and delivery deadlines. The company, however, spent over $1 billion in R&D, and would not have been able to receive funding in time through the traditional IPO route. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic complicated the execution of roadshows, which were conducted through a series of in-person events between a company and its investors, that are now required to be fully online. This slowed down the process of IPOs even further, which became another incentive for companies to choose the SPAC route. Also, finance figures have further added credibility to the investment instrument, including Bill Ackman through Pershing Square Tontine Holdings, which raised $4 billion in the largest SPAC IPO in July 2020, in addition to Michael Klein with Churchill Capital and Chamath Palihapitiya with Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings.

Special-Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) were created in 1993 but did not become significant until recently. In 2019 there were 59 SPAC IPOs, raising over $12 billion. However, in 2020 there were more than four times as many SPAC IPOs, raising over $75 billion. A SPAC is an alternative to an IPO, or a reverse takeover (less common) and it is essentially a new route to access the capital markets. It is set up by a sponsor, who is responsible for raising a blank check from investors. The structure of a SPAC is such that it democratizes public offerings by allowing non accredited investors to invest alongside the sponsors, thus providing investors with opportunities they might otherwise have missed. For instance, in one of the highest profile IPOs in 2020, Airbnb stock opened the first day of trading at a price that was two times greater than the price set at the IPO. However, had the company gone public through a SPAC, it would have given the public the opportunity to buy at a small premium to the acquisition price.

At the same time, the SPAC may also be beneficial to the company going public, since it provides with superior price discovery, given that the price is not set by the projections of the bankers, but rather by competing sponsors. A SPAC transaction is usually less cumbersome for the company, to the extent that they are prepared for a public offering. There is much less scrutiny by auditors, or regulating bodies such as the SEC, therefore a SPAC transaction may allow the company to go public months before it would if they were doing an IPO. Furthermore, the management would be allowed (and encouraged) to focus on running the business, since this would be in the best interests of the sponsors. The company also has the added benefit of receiving an approval stamp from respected long-term investors. Despite having similar underwriting fees, SPACs are also cheaper for the company due to lower direct expenses and indirect costs. The company management is also commonly allured by higher liquidity, since there is no lock-up period in a SPAC transaction.

In 2020, some of the best-known investors in the world raised or invested in SPACs, such as Apollo, Third Point, Pershing Square, or Coatue. Sponsoring a SPAC is particularly enticing to investors, since they typically retain 20% of the shares in the newly formed company. Thus, it is reasonable to project that, barring a stock market crash, SPACs should continue increasing in volume. To put it in perspective, even top investors such as Bill Ackman have stopped charging a 2 and 20 fee in their funds. Here, instead, a sponsor that makes a 10-billion-dollar acquisition could immediately receive $2 billion in revenues. However, that dilution comes at a cost to those investing alongside sponsors, since they must believe that the sponsor can turn every 1 dollar into 2.5 over a period of 7 years (assuming a 10% hurdle rate). Thus, investors should look for SPACs where the sponsor’s incentives are aligned with their own, as opposed to asset gatherers. Furthermore, investors must beware that there might not be a sufficient supply of high-quality companies given the growing number of SPACs seeking a target.

The rise of SPACs

In the early 1990s, SPACs only played a small role within niche industries such as tech and commodities, as they provided private companies with the necessary growth capital at a faster pace during economic downturns. Blank check companies, however, were widely mistrusted by institutional and retail investors alike due to a combination of inadequate SEC regulation, in addition to unconstrained practices in the 1980s. These resulted in less prepared private companies joining the public market and displaying a weak track record in comparison to larger companies that would undergo a traditional IPO, thus damaging the reputation of their respective SPAC. As a result, the average SPAC would raise no more than $100 million, in comparison to today’s average of almost $400 million.

With the growth of private equity funds in the early 2000s and the proceeding legitimisation of SPACs by investment banks, their popularity began to rise. What followed were a series of SEC measures undertaken to protect investors, which increased transparency and removed listing fees in relation to the issuance of additional shares. During the 2008 financial crisis, distrust of markets became the norm, so the sole US SPAC IPO only raised a mere $36 million. By 2017, however, this distrust had slowly dissipated, and the first SPAC was listed in the NYSE. Now, the exchange reported over 50 individual SPACs in less than 5 years, which are responsible for the NYSE’s top listing volume in 2020. Due to the smaller size of early SPACs, most avoided large stock exchanges considering high transaction fees, but the increased visibility to recent investors now became an attractive feature to SPAC managers. Additionally, bulge bracket banks such as Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse have lifted restrictions against SPACs over the past 5 years and have consequently started their own.

Another key cause of the increase in popularity of SPACs over the past decade was the improvement in the calibre of companies choosing this method over a traditional IPO. Some critics argued that early-stage companies with less funding possibilities harmed the overall reputation of SPACs, as they would often underperform in the long-run. Virgin Galactic’s SPAC IPO in 2019, for example, raised questions regarding how appropriate it is to take a company public, if it is unprepared to meet cost obligations and delivery deadlines. The company, however, spent over $1 billion in R&D, and would not have been able to receive funding in time through the traditional IPO route. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic complicated the execution of roadshows, which were conducted through a series of in-person events between a company and its investors, that are now required to be fully online. This slowed down the process of IPOs even further, which became another incentive for companies to choose the SPAC route. Also, finance figures have further added credibility to the investment instrument, including Bill Ackman through Pershing Square Tontine Holdings, which raised $4 billion in the largest SPAC IPO in July 2020, in addition to Michael Klein with Churchill Capital and Chamath Palihapitiya with Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings.

The recent rise of SPACs in Europe

“Europe needs more growth capital to support companies and the SPAC can be the missing instrument between a traditional IPO and private equity financing” .

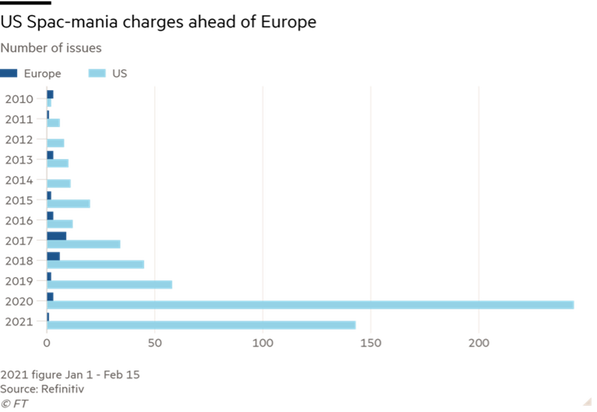

SPACs have gained interest over the last year to become Wall Street’s most popular corporate story. Last year, despite the economic recession caused by the coronavirus pandemic, has been the most intense year for SPAC issuances ever. Since the start of 2020, 421 such companies have gone public globally, raising $127 billion; of these, 405 were listed in the US, raising $125 billion. The US is today by far the most active market for this kind of product, however, the surge in popularity of this new type of investment is transmitting to the entire world and to Europe too. From the first graph, it is possible to observe how Europe has lagged the US in the last decade. 2010 has been the only year in which Europe issued more SPACs than the US. However, from that year the number of issues in Wall Street marked an exponential growth that, with only a small drop in 2016, in 2020 reached its peak. On the other side, after 2010, Europe has always been behind and in the last years the gap has widened ever more.

“Europe needs more growth capital to support companies and the SPAC can be the missing instrument between a traditional IPO and private equity financing” .

SPACs have gained interest over the last year to become Wall Street’s most popular corporate story. Last year, despite the economic recession caused by the coronavirus pandemic, has been the most intense year for SPAC issuances ever. Since the start of 2020, 421 such companies have gone public globally, raising $127 billion; of these, 405 were listed in the US, raising $125 billion. The US is today by far the most active market for this kind of product, however, the surge in popularity of this new type of investment is transmitting to the entire world and to Europe too. From the first graph, it is possible to observe how Europe has lagged the US in the last decade. 2010 has been the only year in which Europe issued more SPACs than the US. However, from that year the number of issues in Wall Street marked an exponential growth that, with only a small drop in 2016, in 2020 reached its peak. On the other side, after 2010, Europe has always been behind and in the last years the gap has widened ever more.

Poor track record

The last and only blank-cheque European listing this year has been ESG Core Investments and has been just the fourth since the start of 2020. This issuance raised $250 million, and its focus is an investment opportunity in the European region within industries that have strong Environmental, Social and Governance profiles. Some bankers in recent interviews have declared that the SPAC phenomenon is seriously taking place in Europe and a growing list of issuers is piling over their desks, ready to go on stage with the most hyped corporate story at the moment. Most of the listings are focused on healthcare, technology and consumer sector and exchanges in France, the Netherlands and Southern Europe are going to become the most active of the region.

Indeed, the Dutch capital, for instance, has developed knowledge and expertise in SPAC listing and is likely to become the region’s main listing exchange. Amsterdam is where Pegasus, the special purpose vehicle shortly announced by Bernard Arnault and Jean Pier Mustier, will be launched. The LVMH founder and the former UniCredit chief will join the long list of renowned managers and entrepreneurs who want to sponsor their own SPAC. They created a vehicle to raise hundreds of millions of dollars and to invest in European financial companies. The reason behind their SPAC is that European financial services, in particular asset management, insurance and fintech, are in search for consolidation due to the incredibly low interest rates, new regulations and technological developments that have disrupted their business models.

Why is Europe behind?

The European activity regarding SPAC is increasing, but not competing to the US at the moment.

The possible reasons that can be contemplated to illustrate the lag of the development of this product in Europe are mainly two: structural reasons and investors’ appetite. On the one hand, the first reason concerns the technical challenges that the exchanges face and the need for a change in regulation: indeed, the most appealing center in Europe is Amsterdam that is a place with a flexible and international jurisdiction. While the first reason can be easily fixed, on the other hand there is a question that the European SPAC sponsors ask to themselves before launching it: is investor demand going to be there?

Bruno Badolato

Ana Leticia Raposo

Edoardo Zanetta

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

The last and only blank-cheque European listing this year has been ESG Core Investments and has been just the fourth since the start of 2020. This issuance raised $250 million, and its focus is an investment opportunity in the European region within industries that have strong Environmental, Social and Governance profiles. Some bankers in recent interviews have declared that the SPAC phenomenon is seriously taking place in Europe and a growing list of issuers is piling over their desks, ready to go on stage with the most hyped corporate story at the moment. Most of the listings are focused on healthcare, technology and consumer sector and exchanges in France, the Netherlands and Southern Europe are going to become the most active of the region.

Indeed, the Dutch capital, for instance, has developed knowledge and expertise in SPAC listing and is likely to become the region’s main listing exchange. Amsterdam is where Pegasus, the special purpose vehicle shortly announced by Bernard Arnault and Jean Pier Mustier, will be launched. The LVMH founder and the former UniCredit chief will join the long list of renowned managers and entrepreneurs who want to sponsor their own SPAC. They created a vehicle to raise hundreds of millions of dollars and to invest in European financial companies. The reason behind their SPAC is that European financial services, in particular asset management, insurance and fintech, are in search for consolidation due to the incredibly low interest rates, new regulations and technological developments that have disrupted their business models.

Why is Europe behind?

The European activity regarding SPAC is increasing, but not competing to the US at the moment.

The possible reasons that can be contemplated to illustrate the lag of the development of this product in Europe are mainly two: structural reasons and investors’ appetite. On the one hand, the first reason concerns the technical challenges that the exchanges face and the need for a change in regulation: indeed, the most appealing center in Europe is Amsterdam that is a place with a flexible and international jurisdiction. While the first reason can be easily fixed, on the other hand there is a question that the European SPAC sponsors ask to themselves before launching it: is investor demand going to be there?

Bruno Badolato

Ana Leticia Raposo

Edoardo Zanetta

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.