U.S. President Donald Trump and his administration have repeatedly expressed their intention to raise tariffs and introduce border taxes penalising imports, claiming that doing so will reduce trade deficits and stimulate the US economy. Does it make sense?

The US administration argues that the country’s numerous trade deficits prove the US economy is open to trade. However, trade deficits depend on the relationship between expenses/investments and savings, and they are not an indicator of trade openness. Martin Wolf, editor of the FT, shows that you can combine indices of ‘trade freedom’ with current account balances to evaluate the relationship between trade deficits and trade freedom. But, it turns out, no significant relationship exists.

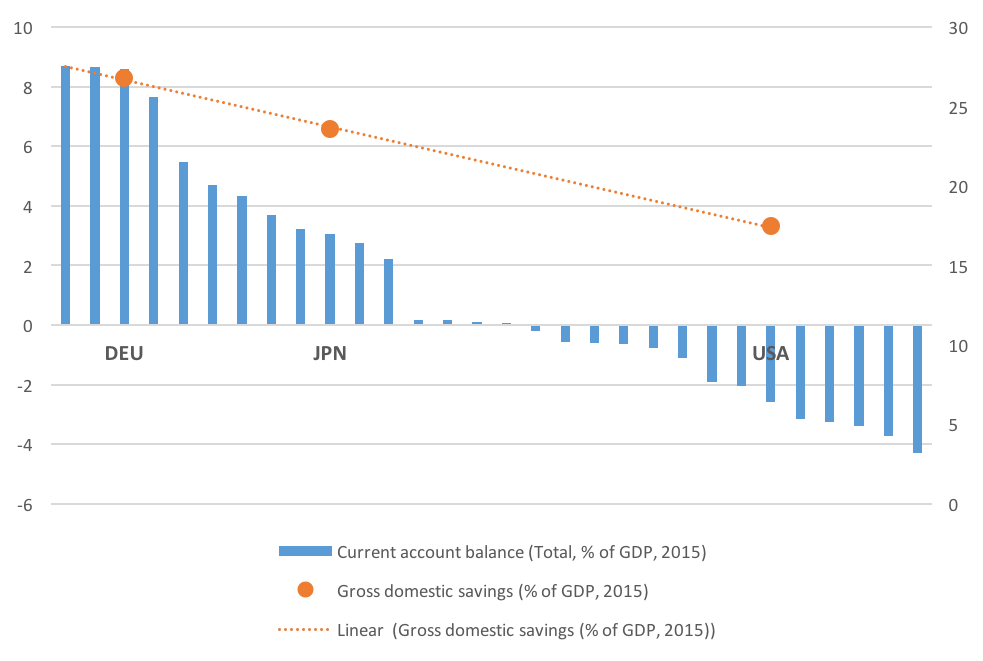

Instead, evidence shows that countries low or negative current account balances (where the current account balance is defined as the sum of the balance of trade – goods and services exports minus imports, net income from abroad and net current transfers) tend to show lower levels of trade freedom. Additionally, low savings are significantly related to low or negative current account balances. In a nutshell, it is reasonable (and correct) to expect a negative current account balance, that is, a trade deficit, for an economy like the US, characterized by a relatively low level of gross national savings (about 19% of the GDP in 2015 against the 28% realised by Germany and the 27% realised by Japan in the same year).

The US administration argues that the country’s numerous trade deficits prove the US economy is open to trade. However, trade deficits depend on the relationship between expenses/investments and savings, and they are not an indicator of trade openness. Martin Wolf, editor of the FT, shows that you can combine indices of ‘trade freedom’ with current account balances to evaluate the relationship between trade deficits and trade freedom. But, it turns out, no significant relationship exists.

Instead, evidence shows that countries low or negative current account balances (where the current account balance is defined as the sum of the balance of trade – goods and services exports minus imports, net income from abroad and net current transfers) tend to show lower levels of trade freedom. Additionally, low savings are significantly related to low or negative current account balances. In a nutshell, it is reasonable (and correct) to expect a negative current account balance, that is, a trade deficit, for an economy like the US, characterized by a relatively low level of gross national savings (about 19% of the GDP in 2015 against the 28% realised by Germany and the 27% realised by Japan in the same year).

Data Source: OECD, The World Bank

So, what will be the consequences of protectionism if the policy proposals of President Trump are successful?

Mr. Wolf argues that taxing imports would also reduce exports. The idea is that lower imports reduce the incentive to produce exports: in the US, we should expect taxes and tariffs to reduce the demand for imports, which, as basic macroeconomic theory teaches us, would result in a rise in the dollar (since the demand for domestic products would be relatively higher). Following a rise in the dollar, however, we would also see a decrease in exports, as these would become more expensive for foreigners. To sum up, lower exports would be a consequence of lower imports if protectionism was successfully executed. Eventually, this would mean that the volume of trade would be lower, without necessarily reducing US trade deficits. Critics to this approach highlight the fact that currency values depend on the exchange rate policies of other countries, which have, indeed, increased their holdings of dollar assets, thereby putting upward pressure on the dollar.

The possible solutions to the trade deficit problem lie, according to Mr. Wolf, in the relationship between savings and investments (which should be clear at this point). If you want to reduce your trade deficit, you must either raise savings or reduce investments. This (almost) leads us to the end of Mr. Wolf’s analysis: since nobody wants to decrease investments, one must necessarily increase savings; to do this, taxes are have to be raised.

Therefore, were the US administration raised taxes, it would likely be able to solve part of its trade deficit problems. Trade deficits are, properly, a worrying topic, since they have contributed to financial instability and weaker national demand in the US.

Yet, one the main promises of the US President during his electoral campaign was to lower taxes. If we learnt something by now, we should know that the effect of a tax reduction would be a further decay of the US current account balances.

It appears the US administration should adjust its conflicting policy objectives.

Gianluca Dimartino

Mr. Wolf argues that taxing imports would also reduce exports. The idea is that lower imports reduce the incentive to produce exports: in the US, we should expect taxes and tariffs to reduce the demand for imports, which, as basic macroeconomic theory teaches us, would result in a rise in the dollar (since the demand for domestic products would be relatively higher). Following a rise in the dollar, however, we would also see a decrease in exports, as these would become more expensive for foreigners. To sum up, lower exports would be a consequence of lower imports if protectionism was successfully executed. Eventually, this would mean that the volume of trade would be lower, without necessarily reducing US trade deficits. Critics to this approach highlight the fact that currency values depend on the exchange rate policies of other countries, which have, indeed, increased their holdings of dollar assets, thereby putting upward pressure on the dollar.

The possible solutions to the trade deficit problem lie, according to Mr. Wolf, in the relationship between savings and investments (which should be clear at this point). If you want to reduce your trade deficit, you must either raise savings or reduce investments. This (almost) leads us to the end of Mr. Wolf’s analysis: since nobody wants to decrease investments, one must necessarily increase savings; to do this, taxes are have to be raised.

Therefore, were the US administration raised taxes, it would likely be able to solve part of its trade deficit problems. Trade deficits are, properly, a worrying topic, since they have contributed to financial instability and weaker national demand in the US.

Yet, one the main promises of the US President during his electoral campaign was to lower taxes. If we learnt something by now, we should know that the effect of a tax reduction would be a further decay of the US current account balances.

It appears the US administration should adjust its conflicting policy objectives.

Gianluca Dimartino