The Euribor uncertainty

The EURIBOR -Euro Interbank Offer Rate- and the LIBOR -London Interbank Offered Rate- are two benchmark rates for short-term transactions, which mirror the cost of unsecured borrowing and include a premium accounting for the creditworthiness of the borrowing institution.

Both rates have been the subject of major rigging scandals in the recent past. Indeed, in 2015 US and UK regulatory authorities fined global banks and traders for a total of $9 billions. Among the busted institutions there were six of the biggest banks worldwide for a total amount of nearly $6 billions: Barclays, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, Royal Bank of Scotland, UBS and Bank of America all paid their ticket for having manipulated the LIBOR interest rate with very noticeable returns stemming from the illegal operation.

Most recent scandals, with regards to the EURIBOR this time, include the Deutsche Bank’s top-player trader Mr Bittar, who pledge guilty against the accuse of having rigged the Brussels interbank rate. Mr Bittar seemed to be recompensed by Deutsche Bank through a system of bonuses at least very generous.

Having stated how easy it is to manipulate the system, European authorities have started to look for a more robust benchmark rate for short-term transactions, which should become active from 2020. However, so far the search has brought little to no results. A possible replacement rate was the Eonia -Euro Overnight Index Average-,which however has been marked off the list of possible future benchmark rates, as it does not match the tough standards decided by the European Authorities.

In the meantime, the financial sector is worried about the availability itself of the Euribor: the number of banks contributing to the data used for publishing the benchmark rate has been considerably slimming down, going from 44 in 2012 to 20 in 2018.

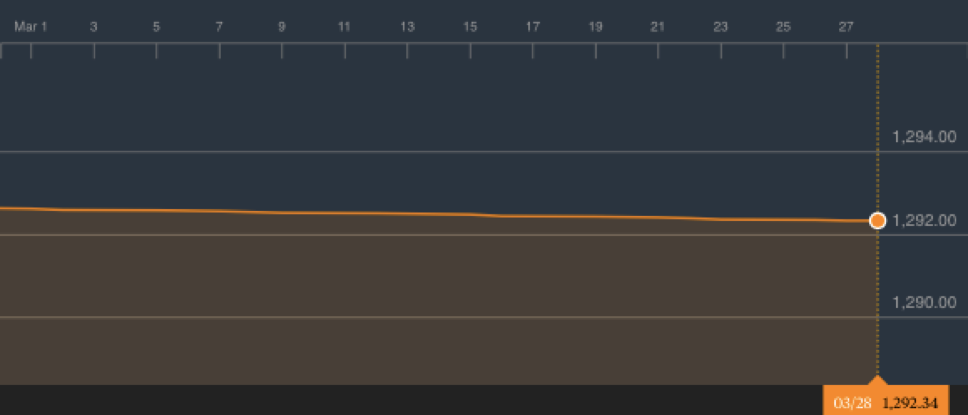

Euribor 3 months

Both rates have been the subject of major rigging scandals in the recent past. Indeed, in 2015 US and UK regulatory authorities fined global banks and traders for a total of $9 billions. Among the busted institutions there were six of the biggest banks worldwide for a total amount of nearly $6 billions: Barclays, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, Royal Bank of Scotland, UBS and Bank of America all paid their ticket for having manipulated the LIBOR interest rate with very noticeable returns stemming from the illegal operation.

Most recent scandals, with regards to the EURIBOR this time, include the Deutsche Bank’s top-player trader Mr Bittar, who pledge guilty against the accuse of having rigged the Brussels interbank rate. Mr Bittar seemed to be recompensed by Deutsche Bank through a system of bonuses at least very generous.

Having stated how easy it is to manipulate the system, European authorities have started to look for a more robust benchmark rate for short-term transactions, which should become active from 2020. However, so far the search has brought little to no results. A possible replacement rate was the Eonia -Euro Overnight Index Average-,which however has been marked off the list of possible future benchmark rates, as it does not match the tough standards decided by the European Authorities.

In the meantime, the financial sector is worried about the availability itself of the Euribor: the number of banks contributing to the data used for publishing the benchmark rate has been considerably slimming down, going from 44 in 2012 to 20 in 2018.

Euribor 3 months

Source: Bloomberg

Another issue is represented by the variable interest financial instruments tied to the EURIBOR: if the latter is to disappear by 2020, instruments linked to it and with maturities longer than the remaining time from now till 2020 are bound to become fixed-rate instruments with interest rate equal to the last value of Euribor published.

A special note must then be added for Italy, whose capital tied to the Euribor rate is the highest among the Eurozone Countries: almost €150 billions of Euribor-linked instruments accounting for around 10% of the overall national debt. The reason behind the shift from a domestic to a European benchmark stood in the international investors’ preference of the latter and the willingness of the Italian government of attracting this category of investors. Behind Italy, Ireland and Portugal may be considered as Countries with noticeable exposures -if we don’t compare them to the Italian record- with €15 bn and €7.2 Euribor-linked debt respectively.

Indeed, Countries with considerable borrowed capital in the form of floating interest rates instruments depending on the Euribor -usually taking the Euribor rate at a specific maturity and adding to it a spread- are especially exposed to the uncertainty coming from abandoning the Euribor standard.

However, in order to actually evaluate what this uncertainty will lead to, we have at least to wait for European regulatory authorities to make their move and formalize their decision on the replacement benchmark.

Adriana Messina – 13/04/18

Another issue is represented by the variable interest financial instruments tied to the EURIBOR: if the latter is to disappear by 2020, instruments linked to it and with maturities longer than the remaining time from now till 2020 are bound to become fixed-rate instruments with interest rate equal to the last value of Euribor published.

A special note must then be added for Italy, whose capital tied to the Euribor rate is the highest among the Eurozone Countries: almost €150 billions of Euribor-linked instruments accounting for around 10% of the overall national debt. The reason behind the shift from a domestic to a European benchmark stood in the international investors’ preference of the latter and the willingness of the Italian government of attracting this category of investors. Behind Italy, Ireland and Portugal may be considered as Countries with noticeable exposures -if we don’t compare them to the Italian record- with €15 bn and €7.2 Euribor-linked debt respectively.

Indeed, Countries with considerable borrowed capital in the form of floating interest rates instruments depending on the Euribor -usually taking the Euribor rate at a specific maturity and adding to it a spread- are especially exposed to the uncertainty coming from abandoning the Euribor standard.

However, in order to actually evaluate what this uncertainty will lead to, we have at least to wait for European regulatory authorities to make their move and formalize their decision on the replacement benchmark.

Adriana Messina – 13/04/18