Introduction

What is wealthtech?

In recent years, the wealthtech sector has experienced exponential growth. At its core, wealthtech represents the intersection of technology and accessibility. Driven by an increasingly digitized world, traditional investment institutions as well as various startups have sought to leverage newer technologies to improve their businesses and product lines. This, in conjunction with investors’ desire to be more autonomous in how they invest, has led to the emergence of the wealthtech sector, a subsector of the fintech industry.

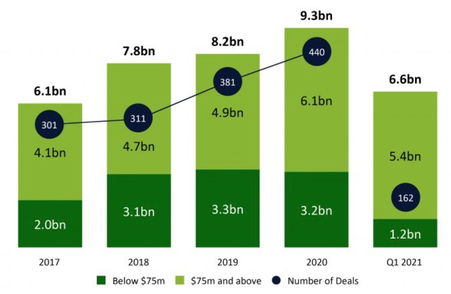

Wealthtech itself is not necessarily new, as aspects of wealth management technology can be seen as early as 2008. However, since that point, interest and user growth in the industry have skyrocketed. In the first quarter of 2021 alone, wealthtech companies raised $6.6bn across 162 transactions and total funding grew at a CAGR of 15.1% - increasing from $6.1bn to nearly $9.3bn at the end of last year.

What is wealthtech?

In recent years, the wealthtech sector has experienced exponential growth. At its core, wealthtech represents the intersection of technology and accessibility. Driven by an increasingly digitized world, traditional investment institutions as well as various startups have sought to leverage newer technologies to improve their businesses and product lines. This, in conjunction with investors’ desire to be more autonomous in how they invest, has led to the emergence of the wealthtech sector, a subsector of the fintech industry.

Wealthtech itself is not necessarily new, as aspects of wealth management technology can be seen as early as 2008. However, since that point, interest and user growth in the industry have skyrocketed. In the first quarter of 2021 alone, wealthtech companies raised $6.6bn across 162 transactions and total funding grew at a CAGR of 15.1% - increasing from $6.1bn to nearly $9.3bn at the end of last year.

Global WealthTech Investment 2017 - Q1 2021. Source: Fintech Global

Aside from the industry’s consistently upward trend, Facet Wealth, a Maryland-based firm in the U.S. speculated on last year’s unprecedented growth. One of its executives Shruti Joshi cited the pandemic environment as a significant motivating factor for consumers to reflect on their lives and how their finances contribute to their long-term goals, which inevitably, led many to seek digital solutions and products in the wealthtech space. This reasoning aligns well with what other wealthtech executives have said about the excitement surrounding the industry. eToro (an Israeli social trading company) former UK CEO Iqbal Gandhi has hinted that wealthtech companies could transform what used to be an "old boys' club" into a much more accessible enterprise. Thus, wealthtech is certainly an expanding industry. But to best understand it and its future potential, it is important to note the different types of technologies that wealthtech captures.

Wealthtech Technologies

One of the most prominent technologies used in wealth management is AI (artificial intelligence). By using machine learning software, companies such as Wealthfront and Betterment in the U.S, Nutmeg in the UK, Wealthsimple in Canada, and Stockspot in Australia have built their businesses on robo-advisors. These systems allow for more evolved market analysis that can account for factors such as the level of a consumer’s risk aversion and their demographics. There are even some robo-advisors that specialize in retirement savings specifically. So, these technologies can provide a much more customized experience.

Furthermore, wealthtech also includes micro-investment firms. Such companies reverse the idea that to invest one needs a larger sum of money. Instead, consumers can invest as little as a few cents per day, and consequently, are more empowered just a little bit each day to take charge of their personal finances.

Perhaps the most widely known form of wealthtech technology is digital brokers. These platforms maintain the spirit of investing ease and accessibility for the average consumer but also incorporate the idea of social trading. Popular digital brokers include eToro, Wellbull, Coinbase, and Robinhood. In addition to trading traditional assets, many of these platforms also allow consumers to trade cryptocurrencies as well.

Finally, other forms of wealthtech include services that make financial news and information more digestible and easily understood.

Moreover, B2C wealthtech technologies aim to make investing easy and palatable, which also means that regardless of the platform’s purpose, there is a growing emphasis on usable interfaces as well as personalized digital spaces for consumers to interact with – this is more of an underlying facet of wealthtech, albeit arguably just as notable.

Finally, there are also wealthtech companies having the purpose of developing technologies to be used by traditional wealth managers, so creating a B2B platform. In line with this, it is widely known that especially in the recent years many financial institutions and asset managers went on "shopping-sprees" of WealthTech companies in order to acquire the technologies, capabilities and data, with the latest one being JP Morgan buying Nutmeg in July 2021 resulting in a valuation of around $900mn. Worth-mentioning also Morgan Stanley buying discount brokerage firm E-Trade in 2020 in a $13bn deal.

Industry Regulation

While it's quite obvious that the wealthtech industry prioritizes the consumer and investing accessibility, an increasingly popular and difficult question to answer is: how will the industry be regulated?

For one, the industry’s high-level involvement of the everyday consumer poses interesting concerns regarding how to best protect the consumer. And given the consumer’s level of autonomy in their own investing strategy, what does this protection look like? Additionally, many wealthtech firms serve clients all across the globe, making industry regulations and regulations much harder to maintain and

streamline. In line with this, there are many debates about how to best regulate this environment, as the RobinHood case showed the world that inexperienced and - in most of the cases - uneducated retail investors have the power to disrupt financial markets, the same financial market where institutional investors, pension funds and mutual funds put their money.

Regulators have long called for increased scrutiny of online brokers, arguing that the near-to-zero and zero commission plans are made to attract retail investors to online trading. The issue here is that whilst these companies make financial markets accessible to everyone, they also allow individuals to risk even significant amounts of money. Particularly, the discussion is centered around the use of leverage and as a result of funds' use of derivatives. For this reason, in July 2018 the ESMA officially ruled on limiting Contracts For Difference (CFDs) and Binary Options, specifically in the promotion and marketing of said products. More specifically, the constraints stand on leverage limits on open positions, negative balance protection, and a margin close-out rule on a per-account basis.

In terms of leverage, the new ruling states that leverage limits are to be set ranging from 30:1 for major currency pairs to 2:1 for cryptocurrencies, as well as a standardized risk warning including the percentage of losses on a CFD provider’s retail investor account.

Furthermore, there is much contention with regard to the crypto industry, and because of the evolving intersection between wealthtech (particularly social trading platforms) and crypto, this uncertainty warrants discussion. Presently, it is unclear how the industry will be regulated as it continues to grow. For example, in the U.S., Former CFTC (Commodity Futures Trading Commission) chairman J. Christopher Giancarlo advised that "we not apply 90-year-old laws -- which is effectively what we have for the Commodities Exchange Act and the Securities Exchange Act -- against a new innovation [crypto] that was never contemplated in the 1930s when those rules were written." However, current CFTC chairman, Rostin Behnam, called on Congress on Wednesday (October 27, 2021) to consider expanding his authority to police cryptocurrency markets.

Regardless, the complexity surrounding compliance and regulation for wealthtech firms has been identified as a significant challenge and potentially alarming hindrance to firms' ability to expand internationally and succeed in the industry – as failure to comply and adapt could mean large fees and legal action. Accordingly, the relatively nascent wealthtech industry and its undetermined regulatory policies have given rise to a complementary industry to help combat these uncertainties, the Regtech industry. Regtech firms have evolved to help meet firms' needs during this time. In fact, earlier this month, FrankieOne, an Australian Regtech firm, raised $20 million in series A funding.

Nevertheless, the first steps towards regulating the industry were recently taken. Effectively, the SEC extended its power over crypto regulation, blocking CoinBase from offering its customers the option of earning interest on their crypto assets. Moreover, SEC Chair Gensler while publicly standing against cryptocurrencies, keeps calling for more regulation on this area, so it wouldn't be surprising if it arrives soon.

The Robinhood Case

2020 was a wildly dynamic year that brought dramatic changes across all walks of life – changes felt by everybody from retail workers to corporate office staff. With offices around the world sitting deserted as companies' workers found themselves behind computer screens at home and over 6 million Americans finding themselves unemployed, people began to question and reflect on the

stability of their livelihoods. What was the solution to this newfound income instability? For many, it was retail trading made possible through apps like Robinhood, Fidelity, or Interactive brokers.

Robinhood was founded in 2013. The name alludes to a legendary fairytale character who took from the rich and redistributed wealth to the poor, suggesting the app was designed to be used by anybody, regardless of their income bracket. In fact, Robinhood allows its 13 million subscribers to buy fractional shares, sometimes with values as low as $1. This is reflected in the size of Robinhood’s average trading account, which was said to be just $5,000 in February, compared to its competitor ETrade’s average of $130,000.

The increased popularity of Robinhood can also be attributed to its offering of crypto-currencies, which accounted for approximately $230 million of its revenues in Q2 2021, up from roughly $10 million in the same quarter of 2020. However, these revenues largely hinge on the performance of the cryptocurrency market, as seen by crypto-related revenues falling to just $50 million in Q3 2021, which corresponded with a drop in Bitcoin’s price from a high of $65,000 in April, to just $30,000 in July (Bitcoin is currently priced at $60,660 as of 31/10/2021 at 19:00 CET).

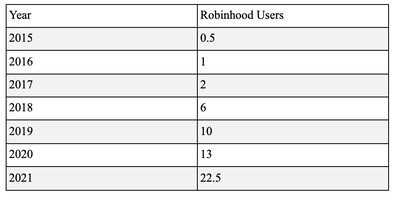

Source: Business of Apps

However, despite Robinhood's significant user growth in recent years, the firm has faced mounting criticism, stemming from allegations of market manipulation, data farming, and exposing unknowledgeable and uneducated clients to the risks of options trading.

Robinhood’s video-game-like user interface has made trading easier and more accessible than ever before, but it must be remembered that successful day-trading and options trading requires extensive experience and knowledge. In February 2021, Robinhood was sued by the parents of 20-year-old Alex Kearns for "unfair business practices" as well as "wrongful death," after it was found that the student had committed suicide after falsely believing that he owed over $730k to Robinhood. Despite sending multiple emails, Kearns was unable to receive any meaningful support from the broker and was only informed after his death that his margin call had been met. Some critics point to features such as confetti animations after completing a trade as the "gamification" of trading, which distracts the user from the fact that they are trading with real money and take a very real amount of risk.

William Galvin, the chief financial regulator for the state of Massachusetts, accuses Robinhood of empowering those who have insufficient knowledge and experience trading to trade. A study of the app’s users in Massachusetts alone found over 600 users who were not adequately knowledgeable or qualified to trade options, even when held to Robinhood’s lax standards (stating you have “not much'' investment experience during the sign-up questionnaire was sufficient to be allowed to trade options). In his suicide note, Alex asked the question: "How is a 20-year-old with no income able to get nearly $1 million worth of leverage?".

The firm has since revised its requirements for options trading, but questions remain as to how this should be regulated across the industry. According to Barron, 90% of traders lose money on options contracts, so is it reasonable to allow retail traders to undertake such extreme gambles? Certain companies, such as the leading cryptocurrency exchange Coinbase, have introduced initiatives to educate retail investors on the commodities they are trading, such as giving cryptocurrencies as rewards for completing brief lessons. Robinhood has also faced scrutiny and criticism for engaging in a practice known as “pay for order flow”, wherein it sold order book information data to HFTs such as Citadel, earning them over $150m in revenue in 2020. The practice has again raised the question of whether the app really works to “democratize finance for all”, as written in its mission statement when PFOF is a practice that results in big market players capitalizing off retail investors’ moves.

Conclusion

In conclusion, one can certainly expect to see increased regulation and heightened scrutiny over the coming period in addition to existing regulations becoming more stringent. However, it is still too early to forecast what direction regulators will pursue with regard to crypto. Nevertheless, the huge rise that the wealthtech industry saw in the past few years did not come unnoticed, with partnerships with financial institutions and ecosystems rapidly arising. If it is true that these companies were born with the purpose of democratizing wealth management, retirement funds, and financial markets, one can not help but wonder: Will “new” wealth management coexist with traditional wealth managers? Will we see more partnerships and M&A in the industry, or will eventually one of the two cannibalize the other? There is no crystal ball to see where this is going, but it is safe to say that the direction regulation will take will be key to answering this question.

Chiara Benedetta Allievi

Matthew Gleeson

Ava Trahan