General Electric (GE) is a worldwide operating US-American high-tech industrial company headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. The company serves customers in different regions of the world, with a focus on its home country: 44.35% of GE’s revenues in 2020 came from the United States, around 20.37% from Asia, and 19.76% from Europe. The Middle East and Africa (9.62%) and the Americas (5.90%) only contributed to a smaller portion of revenue. GE was formed in 1892 as a merger of the two electric companies Thomsom-Houston Electric Company and Edison General Electric Company. Throughout its almost 130 years of history, GE relied on various acquisitions to expand, and it operated in numerous different business segments, such as radio, television, power generation, and computing. The acquisitions eventually made GE America´s best-known industrial conglomerate. As a result of various disposals and divestments, GE nowadays retains significant market share in Aviation (around 20%), Energy Infrastructure (around 32%), Healthcare (around 26%), and Energy (around 41%). Now this giant conglomerate will soon come to an end: from 2023 onwards GE will be divided into three different companies focused on renewable energy, aviation and healthcare. However, before analysing the key elements of the deal we must understand what exacly is a conglomerate and how it developed.

A conglomerate is a firm composed of independent entities engaging in activities typically different from one another, but which still have to refer to the parent company. The main rationale behind conglomerates is that they allow firms to differentiate by operating in different markets. In this case a firm can be more protected from the economic cycles of certain industries thanks to the fact that it is supported by the profitability of other industries. Further benefits derive from the fact that conglomerates can benefit from economies of scale in production, technological expertise and research synergies.

The trend to form conglomerates started to develop in the 1920’s as firms started integrating vertically and horizontally with the objective of benefiting from economies of scale and scope. An example of this trend is the incorporation of General Motors Company in 1908 to unite different motorcar companies such as Cadillac and Marquette. Successively in 1918 it merged with Delco Products (producer of radios and electronics for cars) and Fisher Body corporation (producer of the closed body coupe). These entities were controlled by the principal firm in a multidivisional form, in which each division was responsible for its operations and profit, while the main corporation’s management decided the overall strategy and monitored the divisions. This trend was interrupted in 1950 with the passing of the “Celler-Kefauver Act”, sometimes referred to as the anti-merger act. This act implied that mergers and acquisitions of outstanding shares by companies would be scrutinized in order to prevent the accumulation of excessive market power through vertical and horizontal mergers. While the market power gained by horizontally acquiring competitors was already checked, the act introduced greater controls on vertical mergers, which can be especially harmful to competition if a firm buys its competitors’ suppliers. The implications of this act was that firms wishing to expand through acquisition could only do so by diversifying into different industries, supporting the “firm as portfolio” model. What followed was a massive increase in conglomerate mergers in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

In the 1990’s however there was a process of deconglomerization arising from a series of changes in the regulatory market and corporate practices. The antitrust controls that had been introduced in 1950 over horizontal and vertical mergers were relaxed, making it possible for firms to improve their efficiency and market power within their production chain. Also, it was realized that the stock market undervalued conglomerates compared to the value attributed to the separate business entities, a condition named conglomerate discount. In addition to this, the Reagan-era regulatory policy supported “bust up” takeovers, in which profits were generated by acquiring conglomerates such that they could be sold in separate parts. The often-inadequate reasons why firms were acquired, such as managers' self-interest or in response to the general trend of diversification, sometimes lead to acquisitions of firms that did not leverage on the principal firms’ core competencies, preventing synergies to be created. Due to this reason, firm performances often declined after the acquisition, causing many managers in the 1990’s to sell the previously acquired unrelated divisions to focus on their core competencies. Studies from 2013 have revealed however that conglomerates are extremely prevalent in developing markets, such as India where over 95% of Indian businesses belong to conglomerates. This can be attributed to the advantage they hold compared to smaller firms with regards to access to capital markets, to developing internal talented labour markets and to interacting with the local government.

A conglomerate is a firm composed of independent entities engaging in activities typically different from one another, but which still have to refer to the parent company. The main rationale behind conglomerates is that they allow firms to differentiate by operating in different markets. In this case a firm can be more protected from the economic cycles of certain industries thanks to the fact that it is supported by the profitability of other industries. Further benefits derive from the fact that conglomerates can benefit from economies of scale in production, technological expertise and research synergies.

The trend to form conglomerates started to develop in the 1920’s as firms started integrating vertically and horizontally with the objective of benefiting from economies of scale and scope. An example of this trend is the incorporation of General Motors Company in 1908 to unite different motorcar companies such as Cadillac and Marquette. Successively in 1918 it merged with Delco Products (producer of radios and electronics for cars) and Fisher Body corporation (producer of the closed body coupe). These entities were controlled by the principal firm in a multidivisional form, in which each division was responsible for its operations and profit, while the main corporation’s management decided the overall strategy and monitored the divisions. This trend was interrupted in 1950 with the passing of the “Celler-Kefauver Act”, sometimes referred to as the anti-merger act. This act implied that mergers and acquisitions of outstanding shares by companies would be scrutinized in order to prevent the accumulation of excessive market power through vertical and horizontal mergers. While the market power gained by horizontally acquiring competitors was already checked, the act introduced greater controls on vertical mergers, which can be especially harmful to competition if a firm buys its competitors’ suppliers. The implications of this act was that firms wishing to expand through acquisition could only do so by diversifying into different industries, supporting the “firm as portfolio” model. What followed was a massive increase in conglomerate mergers in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

In the 1990’s however there was a process of deconglomerization arising from a series of changes in the regulatory market and corporate practices. The antitrust controls that had been introduced in 1950 over horizontal and vertical mergers were relaxed, making it possible for firms to improve their efficiency and market power within their production chain. Also, it was realized that the stock market undervalued conglomerates compared to the value attributed to the separate business entities, a condition named conglomerate discount. In addition to this, the Reagan-era regulatory policy supported “bust up” takeovers, in which profits were generated by acquiring conglomerates such that they could be sold in separate parts. The often-inadequate reasons why firms were acquired, such as managers' self-interest or in response to the general trend of diversification, sometimes lead to acquisitions of firms that did not leverage on the principal firms’ core competencies, preventing synergies to be created. Due to this reason, firm performances often declined after the acquisition, causing many managers in the 1990’s to sell the previously acquired unrelated divisions to focus on their core competencies. Studies from 2013 have revealed however that conglomerates are extremely prevalent in developing markets, such as India where over 95% of Indian businesses belong to conglomerates. This can be attributed to the advantage they hold compared to smaller firms with regards to access to capital markets, to developing internal talented labour markets and to interacting with the local government.

The General Electric Case

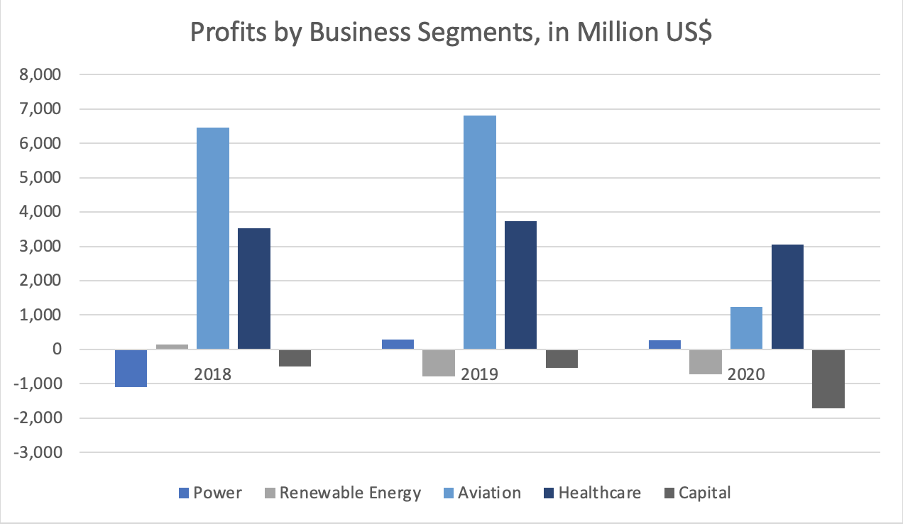

At the end of 2020, GE only operated and reported revenues and profits in five main business segments: Power, Renewable Energy, Aviation, Healthcare, and Capital. As can be seen in the chart below, all business segments of General Electric were adversely impacted by factors relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. The negative effect was especially strong for the Aviation segment and GE Capital’s aircraft leasing business: Global flight schedules were reduced during the pandemic, resulting in lower utilization of aircrafts and lower demand for the products offered by GE.

At the end of 2020, GE only operated and reported revenues and profits in five main business segments: Power, Renewable Energy, Aviation, Healthcare, and Capital. As can be seen in the chart below, all business segments of General Electric were adversely impacted by factors relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. The negative effect was especially strong for the Aviation segment and GE Capital’s aircraft leasing business: Global flight schedules were reduced during the pandemic, resulting in lower utilization of aircrafts and lower demand for the products offered by GE.

Source: GE Annual Report 2020

In its Power business segment, the company offers services and products related to energy production for industrials, governments, and other clients. It is further divided into gas power (such as gas turbines) and a power portfolio (such as steam power technology for fossil and nuclear applications). The Renewable Energy segment is, in contrast, responsible for all of GE´s end-to-end solutions for renewable energy, including offshore wind, hydro, storage, solar, and grid solutions. GE´s most profitable business segment, Aviation, is designing and producing commercial and military aircraft engines as well as aftermarket serviced to support the products. The healthcare unit is offering technologies for medical imaging, digital solutions, patient monitoring and diagnostics, as well as drug discovery and performance improvement solutions. In contrast to the other four business segments, GE also provides financial services and products to its client through the Capital business segment. GE Capital was founded in 1932 and served as the cash cow to GE for a significant amount of time. However, it also proved to be a major liability to GE in the 2008 financial crisis and required a bailout of Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway to stay afloat. For years, GE has sought to exit the risky business of GE capital and sold the bulk of it. The business segment was further split into GE Capital Aviation Services (GECAS) and Energy Financial Services (EFS). In spring of 2021, GE announced that it had agreed to combine GECAS, which offered airplane leasing solutions, with AerCap Holdings N.V., essentially creating a leading franchise in the aviation sector. This is in line with GE´s strategy to turn the company into “a more focused, simpler, stronger company” as CEO Larry Culp appointed. It also allowed GE to generate more than $30bn in proceeds ($24bn in cash, $6bn in ownership of the new company) which is being used to repay its heavy debt burden, for which the company has been criticized for years.

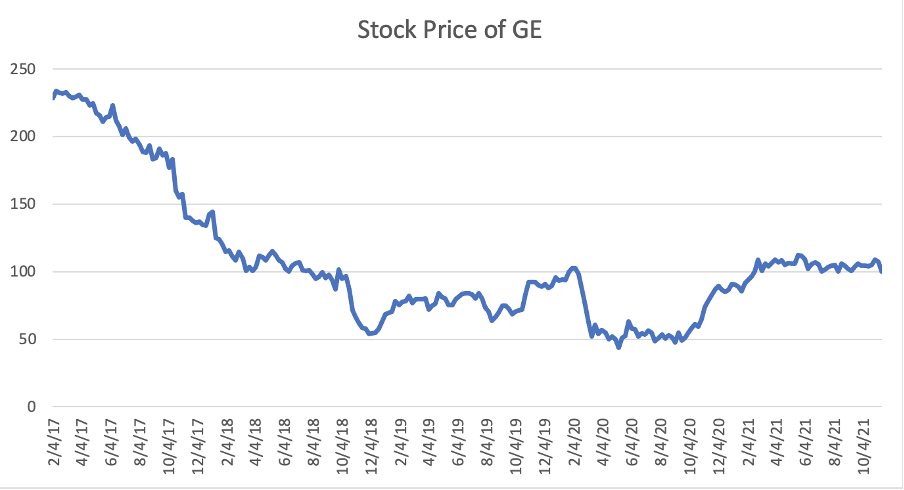

General Electric common stock is listed on the New York Stock Exchange (ticker symbol “GE”) as well as the London Stock Exchange, Euronext Paris, SIX Swiss Exchange, and the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. In 1896, GE was one of the original 12 companies listed on the newly formed Dow Jones Industrial Average. Since then, it remained as one of the 30 components of the Dow Jones from 1907 to 2018 but got replaced by Walgreens Boots Alliance. Before its replacement, GE´s stocks had struggled and underperformed the Dow Jones for more than ten years. Indeed, in the last five years GE has lost around 51%, while the S&P 500 has soared 117%. The historic performance of the stock price can be seen in the graph below.

General Electric common stock is listed on the New York Stock Exchange (ticker symbol “GE”) as well as the London Stock Exchange, Euronext Paris, SIX Swiss Exchange, and the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. In 1896, GE was one of the original 12 companies listed on the newly formed Dow Jones Industrial Average. Since then, it remained as one of the 30 components of the Dow Jones from 1907 to 2018 but got replaced by Walgreens Boots Alliance. Before its replacement, GE´s stocks had struggled and underperformed the Dow Jones for more than ten years. Indeed, in the last five years GE has lost around 51%, while the S&P 500 has soared 117%. The historic performance of the stock price can be seen in the graph below.

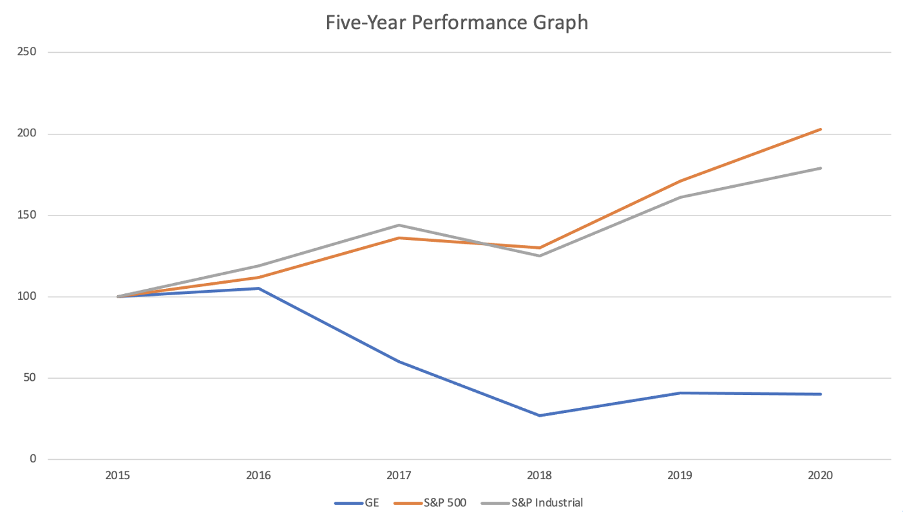

Comparing the performance of GE to both the S&P 500 and the S&P Industrial shows GE’s underperformance: If one invested $100 in GE in 2015, the price at the end of 2020 would have been only $40 in 2020, compared to $203 (S&P 500) and $179 (S&P Industrial).

As GE finds itself to look more and more like a proof of the old academic criticisms of conglomerates: lack of focus and capital misallocation, a GE breakup begins to look plausible. Francesco Cammarota, a Finance Manager at GE, told us “Many conglomerates are struggling, and are generally listed at a discount compared to more specialised companies.”

Outlook

Understanding a conglomerate discount is crucial to recognise the rationale for such a decision. A conglomerate discount occurs from the sum-of-parts valuation, which values conglomerates at a discount versus companies that are more focused on their core products and services. Historically, such a valuation tends to be greater than the value of the conglomerate's stock by anywhere between 13% and 15%. Conglomerates can grow so large and diversified that they become difficult to manage effectively. As a result, some conglomerates may spin off or disinvest subsidiary holdings to reduce the strain on upper management. Such is the current trend for the conglomerate industry, reaching as far as Toshiba in Japan, as well as other firms like Johnson&Johnson which detailed plans to separate its consumer products business from its pharmaceutical and medical device operations.

Some conglomerates like Berkshire Hathaway have managed to escape the market’s inclination to discount over-diversified companies. Conversely, shares of General Electric have tumbled for the past five years from management's inability to focus the company and find meaningful value from each division.

GE has always taken immense pride in its purpose of building a “world that works.” By creating three industry-leading, global public companies, each can benefit from greater focus, tailored capital allocation, and strategic flexibility to drive long-term growth and value for customers, investors, and employees. According to General Electric’s Press Release, their three separate offerings would follow this plan:

The transactions are also subject to a number of other considerations: the satisfaction of customary conditions, including final approvals by GE’s Board of Directors, private letter rulings from the Internal Revenue Service and/or tax opinions from counsel, the filing and effectiveness of Form 10 registration statements with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, necessary to register a class of securities for potential trading on US exchanges, and satisfactory completion of financing.

Deal rationale

The rationale for such a decision would not only be a growth in shareholder value as a result of the removal of the conglomerate discount, but also greater prospects for long-term growth. Such a split would provide deeper operational focus, accountability, and agility to meet customer needs; as well as tailored capital allocation decisions in line with distinct strategies and industry-specific dynamics. Such strategic and financial flexibility to pursue growth opportunities would allow for dedicated boards of directors with deep domain expertise business and industry-oriented career opportunities and incentives for employees and distinct and compelling investment profiles appealing to broader, deeper investor bases. In other words, a complete turnaround of the many inefficiencies GE, as well as many other conglomerates, has been criticised for in recent years.

Stronger financial position

A planned split could build on the meaningful momentum that GE has built in recent years, progressing towards a stronger financial position from which it can afford to undergo such a massive and risky restructuring.

Funding such a drastic restructuring could require very little debt financing given strategic portfolio actions including the recent GECAS transaction, which reduced debt by about $30 billion using transaction proceeds and existing cash sources. GE is expected to achieve a greater than $75 billion reduction in debt as a result of various divestments it has made from 2018 to 2021, which, in combination with the discontinuation of a majority of its factoring programmes, starting as early as the beginning of 2019, will strengthen liquidity and improve cash management, bringing significant change in its management of the timing of incoming cash.

Stronger Business and Operating Performance

Shifting away from a matrix structure towards something that more closely resembles a divisional structure cultivates a platform for clearer leadership and governance. Implementing a decentralized operating model by moving the “centre of gravity” closer to customers would enable stronger customer relationships and operational improvements owed in part to ‘board refreshment’.

Although a product-based structure will inevitably lead to greater duplication of resources as each division will require its own basic functional areas, this should not hinder GE’s ability to achieve economies of scale given that the company spinoffs by themselves will remain industry-leaders. Nevertheless, it may impede synergies across divisions and product lines. In other words, economies of learning may be reduced as the silos of knowledge prove harder to reach those outside your division.

The spinoffs could also improve GE’s operating performance driven by consistent, sustainable free cashflow (FCF), something that Stephen Tusa, a famously GE-perma-bearish analyst, has been particularly critical of until now, which would be largely achieved through a reduction in future repayment of debt – having already reduced it by $75 billion.

Although Tusa remains bearish, it is no longer as a result of the lack of FCF, rather what he believes to be an overly optimistic outlook for GE’s defense business, saying the segment has been “consistently missing targets.” Nevertheless, once GE becomes an aviation-focused company, it should become easier to hit its targets. Furthermore, one must keep in mind that FCF is not everything management should worry about as it frontloads the recognition of investment costs in the first year, which punishes current performance and, at the same time, makes the investment appear free in later periods. Managers whose incentives are linked to FCF, then, are being encouraged to turn down value-creating investments that decrease FCF in the short term. And this can lead to systemic underinvestment over the long term.

Greater financial flexibility could result particularly favourable emerging from COVID-19 headwinds, with low costs of borrowing which GE could take advantage of following what is expected to be an even greater reduction in debt as a result of the spin-offs.

Market Reaction

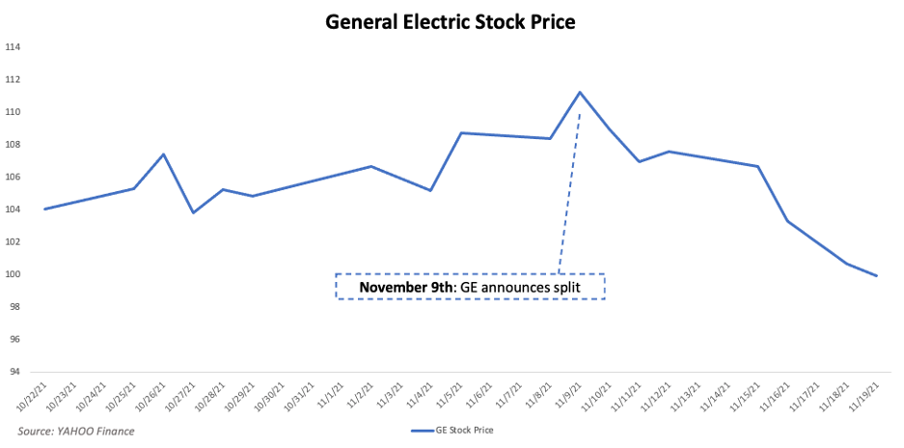

Following the announcement of the split on November 9th, 2021, General Electric’s stock price closed at $111.29, up 2.65% from its previous day’s closing price, suggesting shareholders’ approval of the strategic choice. During the day, the stock was up by as much as 17%. Indeed, some analysts had a favorable view on the split and said it presented a significant upside to GE’s share price. However, in the days following the announcement, General Electric’s shares essentially gave up gains: GE’s closing price of $99.96 on November 19th implied a decline of 7.8% compared to its pre-announcement price of $108.42 on November 8th, as can be seen in the chart below. The sudden decline of General Electric´s share price comes amidst different expectations on its future performance. As a matter of fact, while analysts of Wells Fargo and Deutsche Bank see a potential upside, targeting the share at $120 and $131, some analysts remain rather bearish: in particular, JP Morgan reduced their price targets to only $55 per share, as they believe that both the GE Capital and the GE Renewables business unit are heavily overvalued by other analysts.

Outlook

Understanding a conglomerate discount is crucial to recognise the rationale for such a decision. A conglomerate discount occurs from the sum-of-parts valuation, which values conglomerates at a discount versus companies that are more focused on their core products and services. Historically, such a valuation tends to be greater than the value of the conglomerate's stock by anywhere between 13% and 15%. Conglomerates can grow so large and diversified that they become difficult to manage effectively. As a result, some conglomerates may spin off or disinvest subsidiary holdings to reduce the strain on upper management. Such is the current trend for the conglomerate industry, reaching as far as Toshiba in Japan, as well as other firms like Johnson&Johnson which detailed plans to separate its consumer products business from its pharmaceutical and medical device operations.

Some conglomerates like Berkshire Hathaway have managed to escape the market’s inclination to discount over-diversified companies. Conversely, shares of General Electric have tumbled for the past five years from management's inability to focus the company and find meaningful value from each division.

GE has always taken immense pride in its purpose of building a “world that works.” By creating three industry-leading, global public companies, each can benefit from greater focus, tailored capital allocation, and strategic flexibility to drive long-term growth and value for customers, investors, and employees. According to General Electric’s Press Release, their three separate offerings would follow this plan:

- GE will pursue a tax-free spin-off of GE Healthcare, creating a pure-play company at the centre of precision health in early 2023, in which GE expects to retain a stake of 19.9%. GE also intends that Healthcare will issue debt securities, the proceeds of which will be used to pay down outstanding GE debt, which will not be subject to bondholder consent.

- GE will combine GE Renewable Energy, GE Power, and GE Digital into one business, positioned to lead the energy transition, and then pursuing a tax-free spin-off of this business in early 2024

- Following these transactions, GE will be an aviation-focused company shaping the future of flight.

The transactions are also subject to a number of other considerations: the satisfaction of customary conditions, including final approvals by GE’s Board of Directors, private letter rulings from the Internal Revenue Service and/or tax opinions from counsel, the filing and effectiveness of Form 10 registration statements with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, necessary to register a class of securities for potential trading on US exchanges, and satisfactory completion of financing.

Deal rationale

The rationale for such a decision would not only be a growth in shareholder value as a result of the removal of the conglomerate discount, but also greater prospects for long-term growth. Such a split would provide deeper operational focus, accountability, and agility to meet customer needs; as well as tailored capital allocation decisions in line with distinct strategies and industry-specific dynamics. Such strategic and financial flexibility to pursue growth opportunities would allow for dedicated boards of directors with deep domain expertise business and industry-oriented career opportunities and incentives for employees and distinct and compelling investment profiles appealing to broader, deeper investor bases. In other words, a complete turnaround of the many inefficiencies GE, as well as many other conglomerates, has been criticised for in recent years.

Stronger financial position

A planned split could build on the meaningful momentum that GE has built in recent years, progressing towards a stronger financial position from which it can afford to undergo such a massive and risky restructuring.

Funding such a drastic restructuring could require very little debt financing given strategic portfolio actions including the recent GECAS transaction, which reduced debt by about $30 billion using transaction proceeds and existing cash sources. GE is expected to achieve a greater than $75 billion reduction in debt as a result of various divestments it has made from 2018 to 2021, which, in combination with the discontinuation of a majority of its factoring programmes, starting as early as the beginning of 2019, will strengthen liquidity and improve cash management, bringing significant change in its management of the timing of incoming cash.

Stronger Business and Operating Performance

Shifting away from a matrix structure towards something that more closely resembles a divisional structure cultivates a platform for clearer leadership and governance. Implementing a decentralized operating model by moving the “centre of gravity” closer to customers would enable stronger customer relationships and operational improvements owed in part to ‘board refreshment’.

Although a product-based structure will inevitably lead to greater duplication of resources as each division will require its own basic functional areas, this should not hinder GE’s ability to achieve economies of scale given that the company spinoffs by themselves will remain industry-leaders. Nevertheless, it may impede synergies across divisions and product lines. In other words, economies of learning may be reduced as the silos of knowledge prove harder to reach those outside your division.

The spinoffs could also improve GE’s operating performance driven by consistent, sustainable free cashflow (FCF), something that Stephen Tusa, a famously GE-perma-bearish analyst, has been particularly critical of until now, which would be largely achieved through a reduction in future repayment of debt – having already reduced it by $75 billion.

Although Tusa remains bearish, it is no longer as a result of the lack of FCF, rather what he believes to be an overly optimistic outlook for GE’s defense business, saying the segment has been “consistently missing targets.” Nevertheless, once GE becomes an aviation-focused company, it should become easier to hit its targets. Furthermore, one must keep in mind that FCF is not everything management should worry about as it frontloads the recognition of investment costs in the first year, which punishes current performance and, at the same time, makes the investment appear free in later periods. Managers whose incentives are linked to FCF, then, are being encouraged to turn down value-creating investments that decrease FCF in the short term. And this can lead to systemic underinvestment over the long term.

Greater financial flexibility could result particularly favourable emerging from COVID-19 headwinds, with low costs of borrowing which GE could take advantage of following what is expected to be an even greater reduction in debt as a result of the spin-offs.

Market Reaction

Following the announcement of the split on November 9th, 2021, General Electric’s stock price closed at $111.29, up 2.65% from its previous day’s closing price, suggesting shareholders’ approval of the strategic choice. During the day, the stock was up by as much as 17%. Indeed, some analysts had a favorable view on the split and said it presented a significant upside to GE’s share price. However, in the days following the announcement, General Electric’s shares essentially gave up gains: GE’s closing price of $99.96 on November 19th implied a decline of 7.8% compared to its pre-announcement price of $108.42 on November 8th, as can be seen in the chart below. The sudden decline of General Electric´s share price comes amidst different expectations on its future performance. As a matter of fact, while analysts of Wells Fargo and Deutsche Bank see a potential upside, targeting the share at $120 and $131, some analysts remain rather bearish: in particular, JP Morgan reduced their price targets to only $55 per share, as they believe that both the GE Capital and the GE Renewables business unit are heavily overvalued by other analysts.

Concluding the above, it can be said that GE, the prime example of a conglomerate, is attempting to reawaken its growth through a split into GE Healthcare, GE Renewable Energy, and GE Power, which will be concluded at different times in the near future. Through the split, GE aims to increase shareholder value and improve both its financial condition and operating performance. Even though the stock market’s first reaction was enthusiastic, excitement soon calmed down and GE’s share price has dropped even further. The upcoming months and years will show whether or not GE will be able to overcome its underperformance. In any case, the split demonstrates that even the conglomerates leveraging the most on common expertise, factors of production and economies of scale, are no longer considered more profitable than a simple structure, capable of being rapidly responsive to market demands. While the first wave of conglomerates dismantling in the 1990’s was due to the realisation that acquiring unrelated businesses entailed inefficiencies, a second wave, initiated by GE, could demonstrate that even economies of scale and scope may not be sufficient to balance the organisational issues of conglomerates. The consequence of GE’s decision may therefore be a final deathblow to the existence of conglomerate structures in the western world.

Sources:

● Financial Times

● Ge.com

● Investopedia

● Wall Street Journal

● Bloomberg

Filippo Beni, Sofia Frasson, Jorvis Marxsen

Sources:

● Financial Times

● Ge.com

● Investopedia

● Wall Street Journal

● Bloomberg

Filippo Beni, Sofia Frasson, Jorvis Marxsen