“The period of high growth in the German economy is over for now. But given the strong domestic economy there is no reason to expect a recession,” said Christoph Schmidt, the president of the RWI - Leibniz Institute for Economic Research and chairman of the German Council of Economic Experts.

What makes Germany particularly complex is the fact that its economic expertise is distributed all over the country rather than concentrated in a dominant capital city. This is a consequence of postwar divisions and strong federal states. As a matter of fact, decentralized structure risks tensions on many fronts. Europe’s largest economy is facing a very tough economic period. The German Council of Economic Experts for Economic Research slashed its gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecast for 2019 from 1.5 per cent, which was expected in November, to 0.8 per cent. The decline of the growth forecast has been linked to a downturn especially in the chemical and auto sectors. Given that Germany is home to Volkswagen, Porsche, Mercedes-Benz, Audi and BMW, it’s hard to underestimate a drop of the car production by 9.2 percent in January, as reported by the Economy Ministry. There are other risk factors that could also impact German economy, including a slowdown in Chinese economy and Brexit uncertainty, which was considered as a golden opportunity for Frankfurt to become the new Europe’s top financial centre. Timo Wollmershäuser, head of Ifo Institute for Economic Research business cycle analysis and forecasts, said that “The current production difficulties in German manufacturing are likely to be overcome only gradually […] the industry will largely fail to act as an economic engine in 2019”.

According to Eurostat, Germany’s job vacancy rate has reached its highest ratio since 2009 as well as the highest ratio among the largest economies. The unemployment rate rose to 3.4 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2018, up from 2.8 per cent over the same quarter in the previous year. As a matter of fact, Germany is struggling to recruit workers, particularly in the services sector. The quarterly rate in construction and industry has reached its highest since 2006, attaining 2.9 per cent. Also, the ratio of unfilled positions to the number of jobs filled and unfilled is more than 4 per cent in communication and information, accommodation and food services.

What makes Germany particularly complex is the fact that its economic expertise is distributed all over the country rather than concentrated in a dominant capital city. This is a consequence of postwar divisions and strong federal states. As a matter of fact, decentralized structure risks tensions on many fronts. Europe’s largest economy is facing a very tough economic period. The German Council of Economic Experts for Economic Research slashed its gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecast for 2019 from 1.5 per cent, which was expected in November, to 0.8 per cent. The decline of the growth forecast has been linked to a downturn especially in the chemical and auto sectors. Given that Germany is home to Volkswagen, Porsche, Mercedes-Benz, Audi and BMW, it’s hard to underestimate a drop of the car production by 9.2 percent in January, as reported by the Economy Ministry. There are other risk factors that could also impact German economy, including a slowdown in Chinese economy and Brexit uncertainty, which was considered as a golden opportunity for Frankfurt to become the new Europe’s top financial centre. Timo Wollmershäuser, head of Ifo Institute for Economic Research business cycle analysis and forecasts, said that “The current production difficulties in German manufacturing are likely to be overcome only gradually […] the industry will largely fail to act as an economic engine in 2019”.

According to Eurostat, Germany’s job vacancy rate has reached its highest ratio since 2009 as well as the highest ratio among the largest economies. The unemployment rate rose to 3.4 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2018, up from 2.8 per cent over the same quarter in the previous year. As a matter of fact, Germany is struggling to recruit workers, particularly in the services sector. The quarterly rate in construction and industry has reached its highest since 2006, attaining 2.9 per cent. Also, the ratio of unfilled positions to the number of jobs filled and unfilled is more than 4 per cent in communication and information, accommodation and food services.

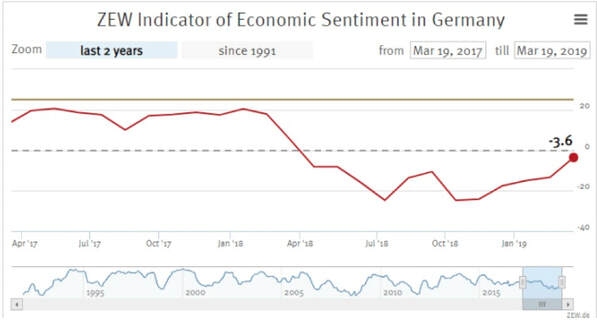

Nevertheless, expectations for Germany’s medium term economic developments are less pessimistic that they were months ago. As stated by Achim Wambach, president of the Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW), progress made in the negotiations between China and the US regarding the trade war, as well as the possible delay in the Brexit process, have contributed. As a consequence, the Zew survey’s indicator of economic sentiment raised from minus 13.4 in January to a level of minus 3.6 points, which is still below the long-term average of 22.2. The Zew indicator is based on the six-months expectations of up to 300 experts from banks, insurance companies and financial departments of selected corporations concerning the economy, inflation rates, interest rates, stock markets and exchange rates in the Eurozone, Germany, Japan, United States, United Kingdom, France and Italy as well as their expectations concerning the oil price.

To conclude, Chancellor Angela Merkel, has avoided to alarm Germans. In an address to the Bundestag, she said that she foresees “times of growth” ahead, while the outlook for the European Union has become “somewhat clouded.”

Ilaria Pagliara

Ilaria Pagliara