The dynamic interplay of mounting interest rates, tax policies, and regulatory changes is currently reshaping European banks. Central banks’ high rates have led to a surge in banks’ profitability. This has prompted diverse responses by governments, including Italy's implementation of a windfall tax and the UK's emphasis on modernising regulations. These varying approaches have tangible impacts on profitability and market valuations, underscoring the challenge of balancing financial stability and public debt servicing in uncertain times

Understanding the Surge in Banks’ Net Interest Income

With inflation rates soaring across the EU and the UK, interest rates have been a key tool for central banks and the restrictive monetary policy adopted seems to be here to stay. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England are dedicated to prioritising inflation targets and have both recently announced that the existing high interest rates will persist. These policies, in turn, affect the actual borrowing and lending rates paid and charged by commercial banks, thus having a tangible effect on European consumers and businesses.

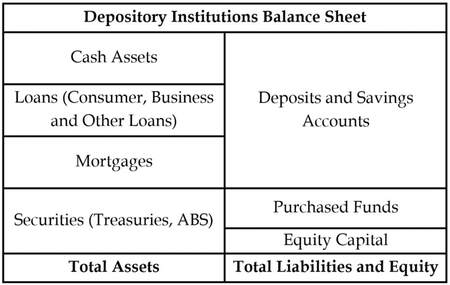

The impact of an interest rate change on commercial banks’ income statement is twofold, affecting both the interest collected on assets and the one charged on the liabilities of a bank. The difference between the revenues generated on a bank’s interest-bearing assets and the interest expense on interest-bearing liabilities is called the Net Interest Income (NII), and can be considered one of the main factors affecting the pricing of a commercial bank’s stock on the market.

The NII changes as assets and liabilities have different characteristics, with rates on deposits, which are liabilities on the bank’s balance sheet, often being much ‘stickier’ than the ones on loans and mortgages, which are assets for the bank. In this context, stickiness refers to the resistance to a quick adjustment in the interest experienced by customers related to the ones set by the central bank. This is partly because many deposits in fixed-term accounts have predefined rates that are fixed until the term of the deposit expires. Therefore, the interest rate paid on deposits increases less than the one received on loans, with NII increasing along with interest rates.

Understanding the Surge in Banks’ Net Interest Income

With inflation rates soaring across the EU and the UK, interest rates have been a key tool for central banks and the restrictive monetary policy adopted seems to be here to stay. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England are dedicated to prioritising inflation targets and have both recently announced that the existing high interest rates will persist. These policies, in turn, affect the actual borrowing and lending rates paid and charged by commercial banks, thus having a tangible effect on European consumers and businesses.

The impact of an interest rate change on commercial banks’ income statement is twofold, affecting both the interest collected on assets and the one charged on the liabilities of a bank. The difference between the revenues generated on a bank’s interest-bearing assets and the interest expense on interest-bearing liabilities is called the Net Interest Income (NII), and can be considered one of the main factors affecting the pricing of a commercial bank’s stock on the market.

The NII changes as assets and liabilities have different characteristics, with rates on deposits, which are liabilities on the bank’s balance sheet, often being much ‘stickier’ than the ones on loans and mortgages, which are assets for the bank. In this context, stickiness refers to the resistance to a quick adjustment in the interest experienced by customers related to the ones set by the central bank. This is partly because many deposits in fixed-term accounts have predefined rates that are fixed until the term of the deposit expires. Therefore, the interest rate paid on deposits increases less than the one received on loans, with NII increasing along with interest rates.

Representation of a typical commercial bank's balance sheet

For completeness, as can be observed above, the interest-bearing liabilities also include purchased funds, which are traded in the interbank market and repriced based on interest rates more dynamically than deposits. However, the effect is marginal as the lion’s share of the right-hand side of the bank’s balance sheet is comprised by the demand deposits and savings accounts, amounting to around three quarters of the total asset value.

The change in NII has been reflected in the income statement of commercial banks over the past years. In the first half of 2023, the six largest Italian banks increased their profits by 60% compared to the same period the previous year. On aggregate, 88% of the increase in total revenues since the first half of 2021 has been due to higher interest income. These “excess profits”, stemming from high interest rates, and not attributable to strategies implemented by the banks, have caught the eye of regulatory entities and governments.

Windfall Taxes and their Effect on Continental European Banks: The Italian Case

Various governments have decided to implement measures to address the excess profits, with manoeuvres differing in approach and substance. Some countries have not been actively charging the banks for these extra profits, some imposing windfall taxes, and others increasing the transparency and communication over the deposit rates.

One of the first nations to address this concern was Spain, where one year ago the Senate granted its ultimate approval for a windfall tax aimed at banks and major energy companies. This tax imposes a 4.8% levy on banks' NII and net commissions exceeding a threshold of €800 million. Similar charges have been imposed in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Lithuania, with the respective rationales being deficit reduction objectives, alleviating the energy crisis, and funding the military sector.

Analogously, on the 7th of August 2023, the Italian Council of Ministers, announced a one-time windfall tax, setting Italy among the latest European countries to intervene. The tax calculation consists of a 40% rate applied to the greatest value between the difference in NII between 2022 and 2021, beyond a 5% increase, and the difference in NII between 2023 and 2021, beyond a 10% increase.

The ECB had warned the Italian government that such move risked making banks more vulnerable in case of a downturn. In fact, taxing an item of bank revenue generates distortive effects on the balance sheet of credit institutions, with negative consequences for their solvency and, in turn, for the economic system. Moreover, taxes on the NII would shift the bank’s incentives away from saving and lending, leading it to focus more on other sources of revenue generation such as fees and trading. Furthermore, the tax may have more drastic effects on smaller local banks subject to less diversification of revenue-producing activities, causing a significant reduction in the amount of loans granted to small and medium-sized enterprises. In addition, altering the credit delivery system creates distortions in the transmission mechanism of monetary policy between member countries, especially with regards to the functioning of the money market.

Following the ECB’s guidance and to facilitate small banks, a further revision of the rule was introduced, providing that credit institutions may choose not to pay the tax, allocating an amount equal to 2.5 times the value of the tax to non-distributable reserves, strengthening the banks’ capital. This modification has not been spared from criticism, as it results in further strengthening of already robust financial institutions. In addition, the upper limit for the levy, has been changed from 0.1% of total assets to 0.26% of risk-weighted assets, excluding government securities.

After the amendments introduced by the government, which provided financial institutions with an alternative to meeting the tax obligation, UniCredit, Italy’s second largest bank, decided to set aside €1.1bn to non-distributable reserves rather than pay €400m in one-off windfall tax, in a move that may set a trend for other lenders. The bank reached a record profit of €6.7bn in the first nine months of 2023, marking an increase of 67.7% YoY.

After UniCredit, Intesa Sanpaolo, the largest Italian banking group, also decided not to pay the extra profit tax. Indeed, the Board of Directors opted for setting aside about €2.01bn to the reserve. Other banks are also likely to choose capital strengthening, thus opting for a lower profit distribution to shareholders.

UniCredit and Intesa Sanpaolo were initially expected to be the main contributors. The events resulting from the windfall tax’s new structure, highlight a significant discrepancy between the expected tax revenue, initially estimated by the government to be around €3bn, and the actual collection, which is lower than anticipated.

From the government’s standpoint, this outcome is unfortunate considering Italy’s debt position, which worsened substantially because of the Covid-19 crisis. As of April 2022, the Italian Government’s debt as a percentage of GDP stood at 145%, a substantial increase from the 134% estimated at the end of 2019. Partly to address the increasing debt issue, European Governments have been broadly imposing revenue-oriented fiscal policies, including windfall taxes on well-performing sectors. The windfall tax applied to banks is indeed not a standalone measure. For example, 24 of the EU countries have implemented a windfall tax on energy companies, justified by the growing energy prices of 2022. Other countries have gone even further, with Croatia and Bulgaria having set economy-wide levies on all thriving businesses.

The Italian case underscores the complex challenge of striking a balance between balancing the books without hampering banks' profitability and solvency. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom (UK), have approached the issue at its foundation, attempting to reduce the gap between the lending rate and the deposit rate, set by commercial banks.

Windfall Taxes and their Effect on Continental European Banks: The Italian Case

Various governments have decided to implement measures to address the excess profits, with manoeuvres differing in approach and substance. Some countries have not been actively charging the banks for these extra profits, some imposing windfall taxes, and others increasing the transparency and communication over the deposit rates.

One of the first nations to address this concern was Spain, where one year ago the Senate granted its ultimate approval for a windfall tax aimed at banks and major energy companies. This tax imposes a 4.8% levy on banks' NII and net commissions exceeding a threshold of €800 million. Similar charges have been imposed in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Lithuania, with the respective rationales being deficit reduction objectives, alleviating the energy crisis, and funding the military sector.

Analogously, on the 7th of August 2023, the Italian Council of Ministers, announced a one-time windfall tax, setting Italy among the latest European countries to intervene. The tax calculation consists of a 40% rate applied to the greatest value between the difference in NII between 2022 and 2021, beyond a 5% increase, and the difference in NII between 2023 and 2021, beyond a 10% increase.

The ECB had warned the Italian government that such move risked making banks more vulnerable in case of a downturn. In fact, taxing an item of bank revenue generates distortive effects on the balance sheet of credit institutions, with negative consequences for their solvency and, in turn, for the economic system. Moreover, taxes on the NII would shift the bank’s incentives away from saving and lending, leading it to focus more on other sources of revenue generation such as fees and trading. Furthermore, the tax may have more drastic effects on smaller local banks subject to less diversification of revenue-producing activities, causing a significant reduction in the amount of loans granted to small and medium-sized enterprises. In addition, altering the credit delivery system creates distortions in the transmission mechanism of monetary policy between member countries, especially with regards to the functioning of the money market.

Following the ECB’s guidance and to facilitate small banks, a further revision of the rule was introduced, providing that credit institutions may choose not to pay the tax, allocating an amount equal to 2.5 times the value of the tax to non-distributable reserves, strengthening the banks’ capital. This modification has not been spared from criticism, as it results in further strengthening of already robust financial institutions. In addition, the upper limit for the levy, has been changed from 0.1% of total assets to 0.26% of risk-weighted assets, excluding government securities.

After the amendments introduced by the government, which provided financial institutions with an alternative to meeting the tax obligation, UniCredit, Italy’s second largest bank, decided to set aside €1.1bn to non-distributable reserves rather than pay €400m in one-off windfall tax, in a move that may set a trend for other lenders. The bank reached a record profit of €6.7bn in the first nine months of 2023, marking an increase of 67.7% YoY.

After UniCredit, Intesa Sanpaolo, the largest Italian banking group, also decided not to pay the extra profit tax. Indeed, the Board of Directors opted for setting aside about €2.01bn to the reserve. Other banks are also likely to choose capital strengthening, thus opting for a lower profit distribution to shareholders.

UniCredit and Intesa Sanpaolo were initially expected to be the main contributors. The events resulting from the windfall tax’s new structure, highlight a significant discrepancy between the expected tax revenue, initially estimated by the government to be around €3bn, and the actual collection, which is lower than anticipated.

From the government’s standpoint, this outcome is unfortunate considering Italy’s debt position, which worsened substantially because of the Covid-19 crisis. As of April 2022, the Italian Government’s debt as a percentage of GDP stood at 145%, a substantial increase from the 134% estimated at the end of 2019. Partly to address the increasing debt issue, European Governments have been broadly imposing revenue-oriented fiscal policies, including windfall taxes on well-performing sectors. The windfall tax applied to banks is indeed not a standalone measure. For example, 24 of the EU countries have implemented a windfall tax on energy companies, justified by the growing energy prices of 2022. Other countries have gone even further, with Croatia and Bulgaria having set economy-wide levies on all thriving businesses.

The Italian case underscores the complex challenge of striking a balance between balancing the books without hampering banks' profitability and solvency. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom (UK), have approached the issue at its foundation, attempting to reduce the gap between the lending rate and the deposit rate, set by commercial banks.

The UK’s Alternative Approach: Effectively Passing Rates on to Depositors

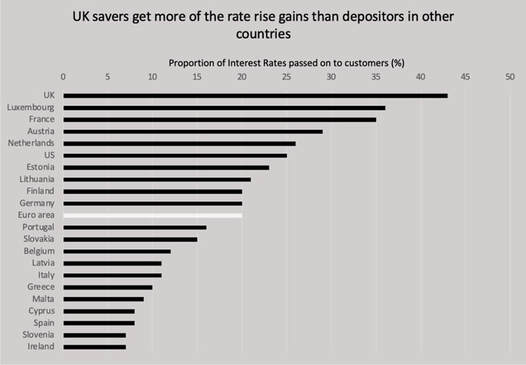

The current unfolding of events in many countries, of which Italy and Spain, points to the banks’ failure at effectively passing on interest rate benefits to their customers. In contrast to these countries, the UK offers an alternative model that focuses on pressuring banks to raise interest rates on savings products, thus ensuring that savers receive more attractive returns. In the UK, consumers collectively hold approximately £1.5 trillion in savings accounts. However, the average rate on a two-year fixed mortgage is significantly higher than the returns on savings accounts (6.52%, compared with just 2.49%), with banks passing on only 43% of the base rate to customers. Larger institutions tend to offer even lower rates, which only exacerbates the issue.

The UK’s Alternative Approach: Effectively Passing Rates on to Depositors

The current unfolding of events in many countries, of which Italy and Spain, points to the banks’ failure at effectively passing on interest rate benefits to their customers. In contrast to these countries, the UK offers an alternative model that focuses on pressuring banks to raise interest rates on savings products, thus ensuring that savers receive more attractive returns. In the UK, consumers collectively hold approximately £1.5 trillion in savings accounts. However, the average rate on a two-year fixed mortgage is significantly higher than the returns on savings accounts (6.52%, compared with just 2.49%), with banks passing on only 43% of the base rate to customers. Larger institutions tend to offer even lower rates, which only exacerbates the issue.

Source: Financial Times, S&P Global Ratings

Unlike countries that resort to heavy taxation, the UK employs regulatory action to influence banks. While the tax on banks recently slightly increased from 27 to 28 percent, the pivotal role in this framework remains the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The FCA has developed 14 points aimed at pressuring banks to raise interest rates on savings products effectively. The UK’s regulatory action emphasizes transparency and fairness. It forces banks to provide fair value assessments and benchmarks for their savings products. Additionally, the FCA publishes rankings of firms' savings rates every six months, reviews the time taken for interest rates to pass on to savings products, and assesses the effectiveness of banks' communications.

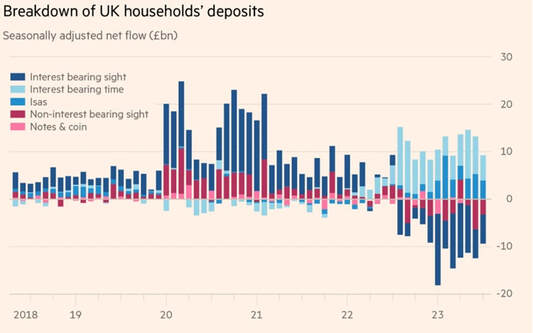

The new economic environment and regulatory actions taken by the FCA have brought a shift in the types of savings accounts people are using, reflecting changing financial behaviours. As depicted in the below graph, the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 saw a surge in deposits into instant access and current accounts (interest bearing and non-interest-bearing sight in the graph), driven by economic uncertainty. However, starting in late 2022, fixed-term savings accounts (interest bearing time and individual savings accounts ISAs in the graph) began to dominate as beneficiaries. For instance, NatWest reported that 15% of its deposits were in term accounts in the third quarter of 2023, up from 11% in June. This trend is part of a broader shift where savers are willing to lock their money away for longer maturities due to the rising interest rate cycle. In the UK, approximately 14 million people now consider savings to be an essential expense, alongside necessities like fuel and bills. Digital challenger banks, such as Monzo, Starling, and Chase UK, have capitalized on this trend, offering higher interest rates compared to traditional banks. While challenger banks have gained ground, traditional banks still dominate the market, increasing their savings market share from 48.3% to 49.7% between January 2022 and March 2023.

Source: Financial Times, Bank of England

The UK's approach fosters a closer relationship between regulators and banks, emphasizing communication. This method is a more long-term process with no guarantee that banks will comply. Success depends on the FCA’s credibility and ability to impose sanctions if banks do not follow the 14 points.

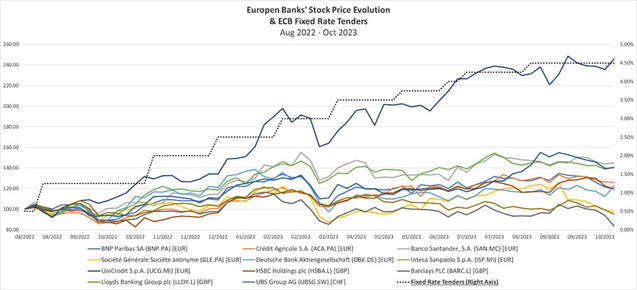

One of the main differences between the two approaches is that the UK one is more gradual and structured, while the windfall tax is singular and, more importantly, unexpected. Consequently, it has a significant impact on the financial markets, leading to a noteworthy reduction in market capitalization for the financial sector upon its announcement. Upon the announcement of the levy, UniCredit's stock fell 5.94%, while Intesa lost 8.67%. Nevertheless, this event occurred within a more favourable context of rising bank prices.

Banking Valuations in a Dynamic Landscape: Trends and Insights

Since the initiation of the ECB’s rate hikes in July 2022, the financial landscape for major banks has undergone substantial changes. Notably, one compelling trend that has emerged during this period is the transformation in the stock prices of European banks. Of the 11 major banks analysed, 8 have seen their stock prices increase by the end of October 2023 compared to August 2022, as depicted in the graph below. This underscores a significant shift in investor sentiment, as they have responded positively to the rising interest rate environment. With the MSCI Europe Financials’ YoY increase of over 40% being a good indicator of the financial sector’s notable performance.

Banking Valuations in a Dynamic Landscape: Trends and Insights

Since the initiation of the ECB’s rate hikes in July 2022, the financial landscape for major banks has undergone substantial changes. Notably, one compelling trend that has emerged during this period is the transformation in the stock prices of European banks. Of the 11 major banks analysed, 8 have seen their stock prices increase by the end of October 2023 compared to August 2022, as depicted in the graph below. This underscores a significant shift in investor sentiment, as they have responded positively to the rising interest rate environment. With the MSCI Europe Financials’ YoY increase of over 40% being a good indicator of the financial sector’s notable performance.

Source: Yahoo Finance, ECB

Even if most European banks have seen an uptick in their stock values, signifying a departure from the historical lows witnessed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, they have yet to reach the pinnacle achieved in 2007. For instance, consider UniCredit: as of the close of trading in October 2023, its stock price was approximately 8.5 times below its peak recorded back in April 2007. This narrative of stock values on the rebound, but still a long way from their historical peaks, holds true across multiple banks. In the case of Deutsche Bank, the contrast is even more striking, with the April 2007 peak towering at 13 times the current stock price. This stems from the heightened capital requirements mandated by the Basel regulations, which have consequently led to a decrease in returns on equity.

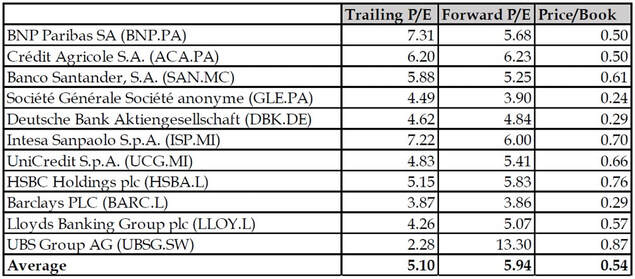

Despite this positive recent evolution, European banks' shares are trading at high book-to-value ratios, with an average price-to-book ratio of 0.54. Similarly, the Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratios show an average of 5.10 for the trailing and 5.94 for the forward P/E. This data underscores the overall trend of modest valuations in the European banking sector.

Source: Yahoo Finance

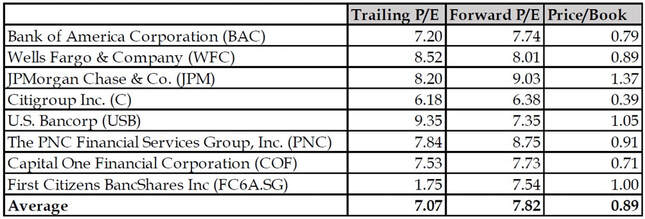

When comparing these metrics to those observed in American banks, it is evident that European ones face more significant discounts. The American banks have an average Price/Book ratio of 0.87, with the Trailing P/E for American banks being approximately 7.83, and the Forward P/E being around 7.86.

Source: Yahoo Finance

The difference in the pricing of European and American Banks might be related to US banks’ heavier focus on secondary activities to commercial banking, such as investment banking and trading. This is true as the valuation of banks is not solely a reflection of their NII driven by interest rate movements. Bank stocks are influenced by a range of factors, including the performance of other divisions within these institutions. For instance, despite its corporate and investment banking division posting a 3% increase in revenues, BNP Paribas share prices dropped by 4% during the early trading hours on October 24th as they reported a significant decline in its Fixed Income, Currencies, and Commodities (FICC) trading division in Q3 2023.

Nonetheless, when a bank's primary source of revenue remains in the commercial side of deposit-taking and lending, its valuation is heavily swayed by NII, as is the case for most European banks. In fact, Santander, the largest Spanish bank, reported a 20% increase in net profit in Q3 2023, driven by a 16% rise in NII. This impacted the stock’s value positively, with the bank’s shares being up 18% YTD, overperforming the overall European banking sector over the same period. This stellar performance is despite having paid hundreds of millions in levies due to windfall extra-profit taxation.

In contrast, the approach set by the UK’s government has had ambiguous effects. On the one hand, one exception in the current earnings season was Barclays, which reported a 16% decrease in profits, leading its share price to fall in October. This decline reflects the notably higher proportion of interest rates passed on to depositors in Britain, as mentioned above. On the other hand, Lloyds surpassed expectations with its third-quarter profits, indicating a lesser impact from the pass-through to depositors compared to Barclays, scoring a 10% increase in NII YoY. Nonetheless, the bank has also cautioned that these benefits are starting to diminish as the interest rates normalise. Similarly, while UniCredit slightly raised its 2023 revenue outlook, primarily due to increased NII, the bank has chosen to keep its profit and investor reward goals unchanged. This decision reflects the bank's cautious approach, as it acknowledges the need for careful deliberation on how best to utilize the "exceptional" growth in earnings.

These cautious predictions could provide some explanation for the lower trading multiples observed in the European banking sector, indicating concerns about their future performance and their impact on valuations.

Conclusion

The current market environment is permeated by uncertainty, with numerous challenges to be faced by banks. A key one is the potential weakening of the boost from higher interest rates, particularly as central banks begin to adopt more accommodative policies. Another aspect to consider is the impact on loan defaults and volumes caused by a potential recession in the Eurozone. Loan volumes have remained stagnant and are even declining in some economies, with provisions for loan losses sharply increasing due to deteriorating credit conditions. This uncertainty is exacerbated by the unknown ripple effects of the policies implemented by the various governments. Only time will tell the long-term effects of the fiscal policies implemented by the continental Europe's governments compared with the British regulatory framework.

By Livio Casali, Maya Doyle, Sofia Rubino, Maxime Vallot

SOURCES

- Financial Times

- Reuters

- ECB

- Yahoo Finance

- CNBC

- EY

- Il Sole 24 Ore

- Deutsche Bank Research

- UniCredit

- Barclays

- Santander