Following the Federal Reserve’s announcement to begin the tapering of its asset purchasing program, a heated debate is taking place among all banks on what investment strategy they should adopt in order to maximize their chances of success in such turbulent and dubious times.

Despite the fact that the largest US lenders could still think of this year in positive terms since they were capable of reporting higher profits with respect to last year due to lower credit costs and strength in fee-based businesses such as trading and investment banking, almost all have struggled to increase revenue because of low interest rates and a slowdown in borrowing.

Taking the latter aspect into consideration, banks are certainly willing to increase their profits, but are actually struggling to use all the deposits piled up on their balance sheets due to the low interest rate environment and the uncertain outlook.

Despite the fact that the largest US lenders could still think of this year in positive terms since they were capable of reporting higher profits with respect to last year due to lower credit costs and strength in fee-based businesses such as trading and investment banking, almost all have struggled to increase revenue because of low interest rates and a slowdown in borrowing.

Taking the latter aspect into consideration, banks are certainly willing to increase their profits, but are actually struggling to use all the deposits piled up on their balance sheets due to the low interest rate environment and the uncertain outlook.

Lending out the money would be the preferred option. However, the fact that companies have found ample liquidity in the bond market and consumers have paid down debts on their credit cards, is resulting in still sluggish loan growth. As reported by CNBC, a credit card debt study by personal-finance site WalletHub affirms that Americans repaid almost $83 billion in credit card debt during 2020, a record.

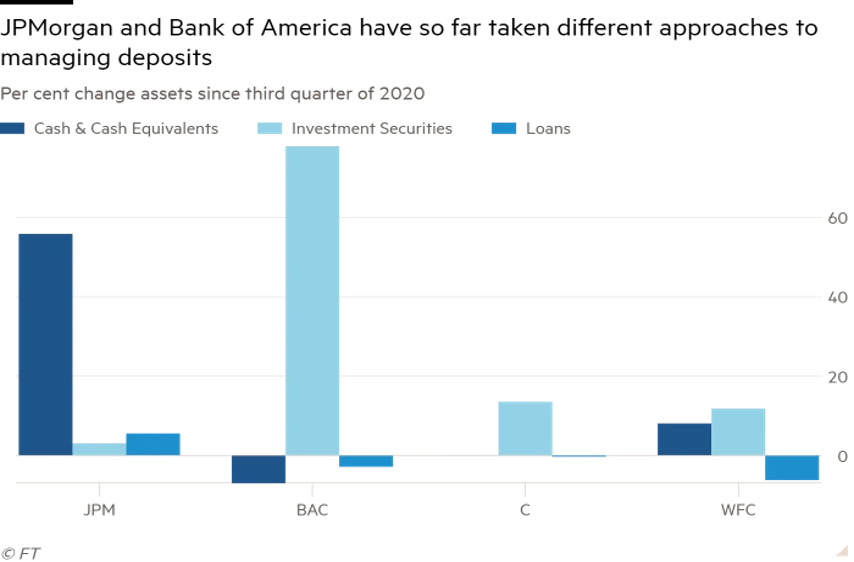

Hence, America’s largest banks have decided to pursue drastically divergent strategies for what concerns redeploying their trillions of dollars of deposit in the government debt markets.

For instance, some banks have begun using the funds to buy Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities in search of yield.

“Right now we have more liquidity sources-cash Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities- than we have loans,” said Paul Donofrio, Bank of America CFO. “That’s a phenomenal statistic.”

As a matter of fact, Bank of America, the second largest lender by assets in the United States, increased its liquidity by purchasing a large amount of debt securities, $470 billion of them over the past year.

Thanks to what can be considered a very aggressive strategy, Bank of America outperformed its megabanks peers, by reporting a 10 per cent increase in net interest income during the third quarter, despite a three percent drop in average loan balances.

Overall the bank’s revenue surged by 12 per cent YOY and topped expectations: an excellent result compared to other institutions such as Wells Fargo and Citigroup that respectively reported declines in revenue of 2 per cent and 1 per cent.

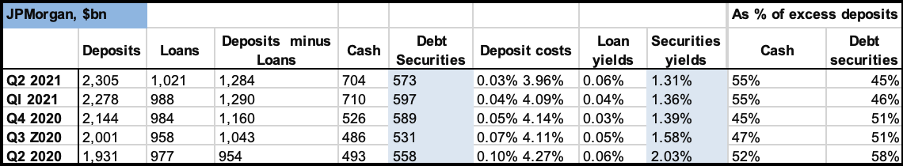

On the other hand, JP Morgan, as precedently mentioned, decided to adopt a different strategy. America’s largest bank kicked off the third quarter earnings season by easily beating analysts’ estimates, with a profit higher than last year. A downturn in bond trading was compensated by strong investment banking income and the release of more than $2 billion in loan-loss reserves. Overall, the return on equity was a remarkable 18 percent. Still, we could say that loan growth remains a thorny issue for the company.

During the quarter, total loans increased by 6 per cent. Nonetheless, if we get behind the headline statistic, it's evident that the bank's asset and wealth management section was the driving force behind this expansion. Indeed, consumer and business borrowing growth remains elusive, and in fact the bank has reported that loans decreased by 2 per cent and 5 per cent YOY, respectively.

However, JP Morgan executives have decided that the money that hadn’t been handed out in lending should be not redeployed in investments at the moment.

Hence, America’s largest banks have decided to pursue drastically divergent strategies for what concerns redeploying their trillions of dollars of deposit in the government debt markets.

For instance, some banks have begun using the funds to buy Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities in search of yield.

“Right now we have more liquidity sources-cash Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities- than we have loans,” said Paul Donofrio, Bank of America CFO. “That’s a phenomenal statistic.”

As a matter of fact, Bank of America, the second largest lender by assets in the United States, increased its liquidity by purchasing a large amount of debt securities, $470 billion of them over the past year.

Thanks to what can be considered a very aggressive strategy, Bank of America outperformed its megabanks peers, by reporting a 10 per cent increase in net interest income during the third quarter, despite a three percent drop in average loan balances.

Overall the bank’s revenue surged by 12 per cent YOY and topped expectations: an excellent result compared to other institutions such as Wells Fargo and Citigroup that respectively reported declines in revenue of 2 per cent and 1 per cent.

On the other hand, JP Morgan, as precedently mentioned, decided to adopt a different strategy. America’s largest bank kicked off the third quarter earnings season by easily beating analysts’ estimates, with a profit higher than last year. A downturn in bond trading was compensated by strong investment banking income and the release of more than $2 billion in loan-loss reserves. Overall, the return on equity was a remarkable 18 percent. Still, we could say that loan growth remains a thorny issue for the company.

During the quarter, total loans increased by 6 per cent. Nonetheless, if we get behind the headline statistic, it's evident that the bank's asset and wealth management section was the driving force behind this expansion. Indeed, consumer and business borrowing growth remains elusive, and in fact the bank has reported that loans decreased by 2 per cent and 5 per cent YOY, respectively.

However, JP Morgan executives have decided that the money that hadn’t been handed out in lending should be not redeployed in investments at the moment.

Jeremy Barnum, JP Morgan’s chief financial officer, affirmed that he was still “happy to be patient” with the firm’s excess deposits while waiting for higher interest rates. In fact, JP Morgan increased by only 3 per cent its security debt portfolio. The rationale for it was made clear by Jamie Dimon, the bank’s CEO, who fears that Treasury prices could fall. As he asserted in a letter to shareholders “It’s hard to justify the price of US debt”, and also a few months earlier he said he “wouldn’t touch (ed. Treasuries) with a 10-foot pole”.

According to Jason Goldberg, analyst at Barclays, in the short run such caution has been costly. If JP Morgan had invested their extra cash at 1.5 per cent it could have increased its pre-provision earnings by 7 per cent from what it was reported in the quarter.

However, if rates move higher, treasuries could fall out of favour with the banks, creating a negative feedback loop in the market.

In order to understand the different choices of the two banks, it is essential to notice what has happened in the last year and a half to the banking sector.

According to Jason Goldberg, analyst at Barclays, in the short run such caution has been costly. If JP Morgan had invested their extra cash at 1.5 per cent it could have increased its pre-provision earnings by 7 per cent from what it was reported in the quarter.

However, if rates move higher, treasuries could fall out of favour with the banks, creating a negative feedback loop in the market.

In order to understand the different choices of the two banks, it is essential to notice what has happened in the last year and a half to the banking sector.

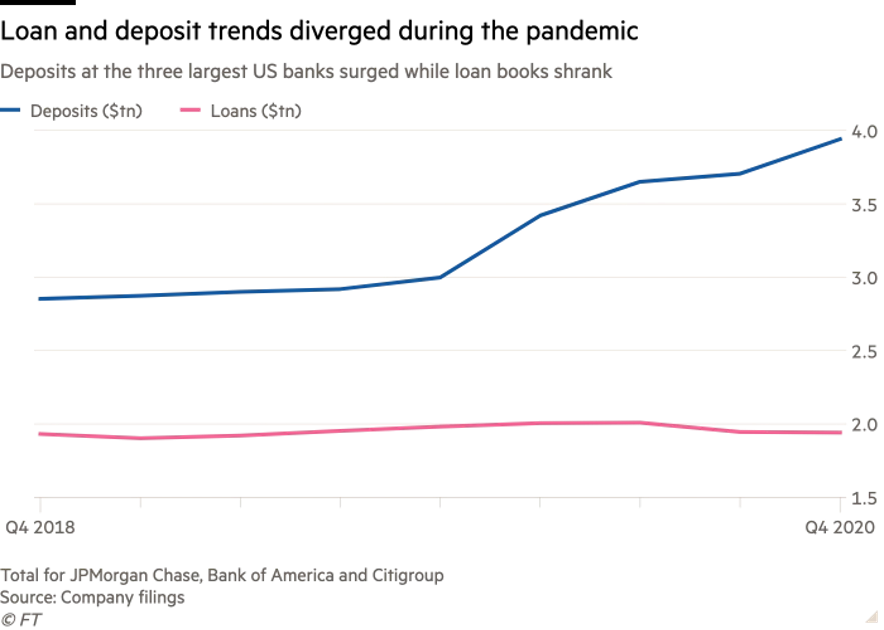

Source: Financial Times

In the first place, the pandemic affected demand, namely, it decreased loan book as a consequence of a drop in customer loans. Specifically, customers could not access physical branches of banks and as the economic activity was temporarily halted they also lacked profitable investment opportunities, which induced them to stop borrowing. However, central banks, afraid that such an economic environment would have drastically affected employment, promptly reacted. The Federal Reserve enacted an expansionary monetary policy and increased the money supply by resuming quantitative easing operations and decreasing the fed fund rate, which is the rate at which banks borrow money overnight. At the same time, as customers lacked opportunities to spend their income, saving hiked by about half a trillion. Concurrently, deposit costs dropped, almost reaching the zero bound but yields on loans, securities, and cash dropped even more. At the moment all banks face the same situations: deposits are increasing for the above-mentioned reasons, but they lack profitable opportunities to invest the excess liquidity.

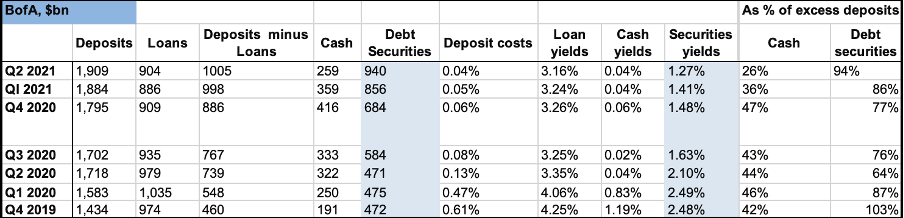

In the spring of 2021, rates started to increase and Bank of America decided to invest its excess liquidity buying $470bn in debt securities, bringing its total near the $1tn threshold and average maturity to four years. To put it in perspective, the Federal Reserve bought $480bn of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in the past year while BofA $360bn. Moreover, there might be some procyclicality relating cash held by the bank and its acquisition of mortgage-backed securities. As a matter of fact, the acquisition of MBS distributed cash to citizens, whose only choice was to put such liquidity in deposits as they lacked the possibility to spend it in the real economy. The increase in deposits automatically increased banks’ excess liquidity. BofA’s decision to invest extra cash is not surprising as it is trying to increase income in a rather unprofitable environment. The gain deriving from such investments in securities amounts to $6bn and does not increase risks nor capital requirements.

Conversely, JP Morgan has not bought securities, even though Deposits exceed Loans by about $1.2 trillion. It seems that BofA believes that current rates are attractive while JP Morgan does not and is waiting to invest at better rates.

In the spring of 2021, rates started to increase and Bank of America decided to invest its excess liquidity buying $470bn in debt securities, bringing its total near the $1tn threshold and average maturity to four years. To put it in perspective, the Federal Reserve bought $480bn of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in the past year while BofA $360bn. Moreover, there might be some procyclicality relating cash held by the bank and its acquisition of mortgage-backed securities. As a matter of fact, the acquisition of MBS distributed cash to citizens, whose only choice was to put such liquidity in deposits as they lacked the possibility to spend it in the real economy. The increase in deposits automatically increased banks’ excess liquidity. BofA’s decision to invest extra cash is not surprising as it is trying to increase income in a rather unprofitable environment. The gain deriving from such investments in securities amounts to $6bn and does not increase risks nor capital requirements.

Conversely, JP Morgan has not bought securities, even though Deposits exceed Loans by about $1.2 trillion. It seems that BofA believes that current rates are attractive while JP Morgan does not and is waiting to invest at better rates.

Source: Financial Times

On the one hand, BofA CEO Brian Moynihan stated that:

“Deposits have crossed $1.9tn and the loans are $900m and change. And that difference has got to be put to work. . . we’re not timing the market or betting. We just sort of deploy it when we’re sure it’s really going to be there.”

On the other hand, JPMorgan’s CFO, Jeremy Barnum, claimed:

“Our central case from an economic perspective is for a very robust recovery, and that’s pretty much a consensus, a view between us, our research team, the Fed, et cetera. And that view is associated with higher inflation, along the lines of the Fed’s own target for higher inflation. All those things together, it’s an outlook that’s associated with higher rates, all else equal. And so, in light of all that, we do remain happy to stay patient here.”

Even though it seems that the two banks are betting on opposing trends, it might not be the case. BofA might simply have a preference to invest extra cash at the best present yield and eventually change their position afterward. Moreover, there are some reasons for which the two positions might seem less conflicting.

“Deposits have crossed $1.9tn and the loans are $900m and change. And that difference has got to be put to work. . . we’re not timing the market or betting. We just sort of deploy it when we’re sure it’s really going to be there.”

On the other hand, JPMorgan’s CFO, Jeremy Barnum, claimed:

“Our central case from an economic perspective is for a very robust recovery, and that’s pretty much a consensus, a view between us, our research team, the Fed, et cetera. And that view is associated with higher inflation, along the lines of the Fed’s own target for higher inflation. All those things together, it’s an outlook that’s associated with higher rates, all else equal. And so, in light of all that, we do remain happy to stay patient here.”

Even though it seems that the two banks are betting on opposing trends, it might not be the case. BofA might simply have a preference to invest extra cash at the best present yield and eventually change their position afterward. Moreover, there are some reasons for which the two positions might seem less conflicting.

- Bank of America is hedging around $150bn of the bond purchased with swaps paying fixed interest and receiving floating. Accounting for the cost of the swaps, the bond's yield is similar to that of cash, with a yield only a few basis points above the rate offered for deposits at the Fed.

- Bank of America has a deposit base dominated by retailers. As such, even if market conditions change, they will not experience large withdrawals. Indeed, financial institutions largely reliant on customer deposits tend not to have large withdrawals as customers tend to stick to their own bank even in periods of uncertainty. On the other hand, banks which depend on the wholesale market experience large fluctuations in periods in which the shape of the yield curve changes. The wholesale market is mainly composed of interbank markets and funds from corporations. As JP Morgan is mainly dependent on corporate clients, it is exposed to potential large withdrawals if conditions of the market contract its position. If JPMorgan invested its liquidity now and then when interest rates rise, its investors would promptly switch their funds to a bank that bet on higher rates. Thus, the choices of the two banks might be simply due to the profile of their depositors rather than on their opinion of future rates.

- JPMorgan has a little margin before failing to satisfy capital requirements ratio, while BofA is in a safer position. Namely, the latter can experience even large losses from its bond position and still satisfy the capital requirements imposed by regulators. Conversely, if the former buys bonds and accounts for them as available for sale securities the loss would directly be reflected in the net income and affect capital.

- The above-mentioned consideration might be the reason why both banks have partially reclassified their portfolio securities as held to maturity rather than available for sale so that an increase in interest rates does not affect capital. However, in order not to excessively impact capital once all the unrealized losses are realized both banks kept a few hundred billion in the AFS.

- JP Morgan is proving to be very profitable thanks to its trading and investment banking business, which brought the bank $10bn in revenue in Q2. As long as the stock market is strong, it can wait to invest in safer securities. On the other hand, BofA tends to take on fewer risks on capital markets, making barely half of the revenues of JP Morgan. Thus, it is prone to invest excess liquidity in safe assets.

The FED Red Herring

Minutes after the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) September meeting, Federal Reserve officials firmed up their plans to begin the tapering, or reduction, of the $120bn monthly asset purchasing program. Having moved closer to achieving “further substantial progress” towards their 2 percent inflation and full employment targets, the Fed could finally warrant a gradual pull back in treasury purchases by $10bn a month, and the purchase of agency mortgage-backed securities by $5bn a month.

During a press conference following their September meeting, Powell hinted that the timeline for this reduction could be as early as mid-November, ensuing a “decent” job report which he believed was more than necessary to consider the employment threshold met, and the unchanged characterization of the recent inflation surge to be merely “transitory”.

However, following the recent surge in global energy prices, investors are now betting that central bankers will back away from their insistence that inflation is transitory, and instead respond with higher interest rates much sooner than projected by the report. This may be confirmed at their next meeting on the 3rd of November. Until then, there will be no real certainty regarding the Fed’s plans. Concerns about inflationary pressures stretching beyond the sectors most sensitive to economic reopening were already expressed by some Fed officials but were not reflected in the final report.

Minutes after the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) September meeting, Federal Reserve officials firmed up their plans to begin the tapering, or reduction, of the $120bn monthly asset purchasing program. Having moved closer to achieving “further substantial progress” towards their 2 percent inflation and full employment targets, the Fed could finally warrant a gradual pull back in treasury purchases by $10bn a month, and the purchase of agency mortgage-backed securities by $5bn a month.

During a press conference following their September meeting, Powell hinted that the timeline for this reduction could be as early as mid-November, ensuing a “decent” job report which he believed was more than necessary to consider the employment threshold met, and the unchanged characterization of the recent inflation surge to be merely “transitory”.

However, following the recent surge in global energy prices, investors are now betting that central bankers will back away from their insistence that inflation is transitory, and instead respond with higher interest rates much sooner than projected by the report. This may be confirmed at their next meeting on the 3rd of November. Until then, there will be no real certainty regarding the Fed’s plans. Concerns about inflationary pressures stretching beyond the sectors most sensitive to economic reopening were already expressed by some Fed officials but were not reflected in the final report.

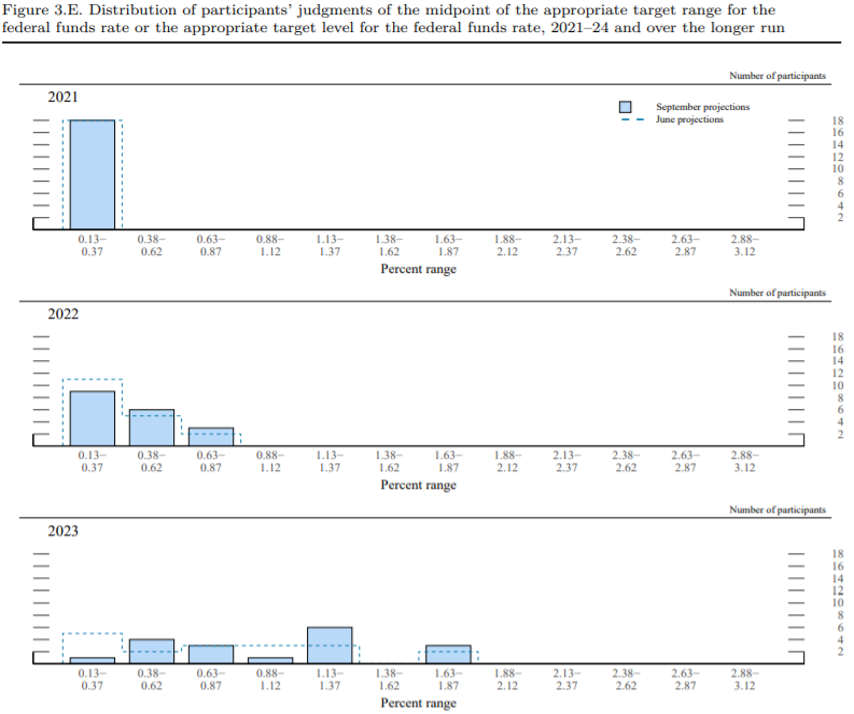

Source: Federal Reserve

As represented above, the June and September FOMC appropriate target range for the fed fund rate forecasts resemble each other quite closely, with short-term rates anchored near zero, and rate hikes only beginning to occur in 2022, with a slight majority pushing that back to 2023.

According to a post-meeting statement by the FOMC, “if progress continues broadly as expected the Committee judges that a moderation in the pace of asset purchase may soon be warranted”. In line with this, it is clear that no final decision has been reached, but a gradual tapering was likely to be appropriate. The tapering decision will be announced at their November meeting and is likely to begin in December.

This decision may not be as clear cut as one may be led to believe by the September report, however. One of the biggest threats to the global economic recovery following the covid crisis will be the possibility of stagflation. The huge mass of accommodative monetary policy by central banks and fiscal stimulus from governments may well fire more inflation. In combination with a number of constraints on the flexibility of production, stagflation is well-within the realm of possibility.

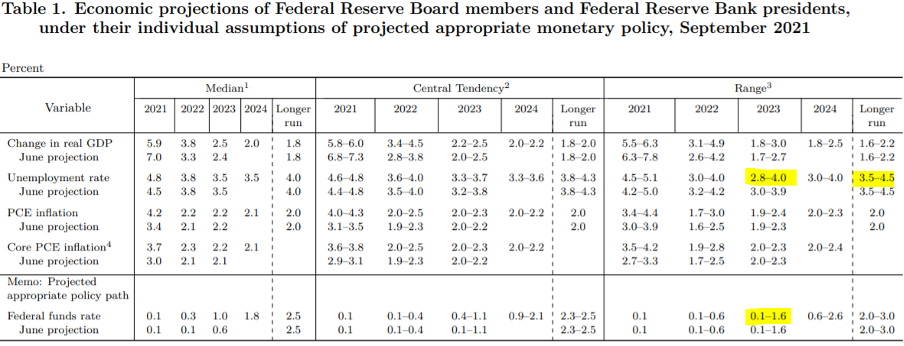

All projections for unemployment and inflation have worsened since the June forecast. Including food and energy, officials expect inflation to run at 4.2% this year, up from 3.4%. The end of year unemployment forecast is now at 4.8%, from the current 5.2%, up from the projected 4.5% in June. This certainly worsens the outlook for stagflation within the US, which has created some division regarding the direction interest rates should take. The Fed must reach a fine balance between raising interest rates to ensure price stability, but not raising them too much as to worsen the outlook for job growth.

Nevertheless, Powell believes that sufficient progress has been made towards reducing the risk of inflation, whereas “the test for substantial further progress on employment is all but met”. Unemployment figures made some officials worry about the same thing and spurred the proposal of another move to double daily market operations of the asset purchasing program to $160bn, leaving the mortgage-backed securities portion at $40bn. However, Powell then clarified he is not looking for a “knockout employment report”, so the inflationary risk that would come with increasing the size of the asset purchasing program would simply be too great and illogical to take.

According to a post-meeting statement by the FOMC, “if progress continues broadly as expected the Committee judges that a moderation in the pace of asset purchase may soon be warranted”. In line with this, it is clear that no final decision has been reached, but a gradual tapering was likely to be appropriate. The tapering decision will be announced at their November meeting and is likely to begin in December.

This decision may not be as clear cut as one may be led to believe by the September report, however. One of the biggest threats to the global economic recovery following the covid crisis will be the possibility of stagflation. The huge mass of accommodative monetary policy by central banks and fiscal stimulus from governments may well fire more inflation. In combination with a number of constraints on the flexibility of production, stagflation is well-within the realm of possibility.

All projections for unemployment and inflation have worsened since the June forecast. Including food and energy, officials expect inflation to run at 4.2% this year, up from 3.4%. The end of year unemployment forecast is now at 4.8%, from the current 5.2%, up from the projected 4.5% in June. This certainly worsens the outlook for stagflation within the US, which has created some division regarding the direction interest rates should take. The Fed must reach a fine balance between raising interest rates to ensure price stability, but not raising them too much as to worsen the outlook for job growth.

Nevertheless, Powell believes that sufficient progress has been made towards reducing the risk of inflation, whereas “the test for substantial further progress on employment is all but met”. Unemployment figures made some officials worry about the same thing and spurred the proposal of another move to double daily market operations of the asset purchasing program to $160bn, leaving the mortgage-backed securities portion at $40bn. However, Powell then clarified he is not looking for a “knockout employment report”, so the inflationary risk that would come with increasing the size of the asset purchasing program would simply be too great and illogical to take.

Source: Federal Reserve

Even within the September forecast, there appears to be great disparity within the ‘Projected appropriate policy path’ into 2023. The proposal to keep rates as low as 0.1 even after the unemployment rate has reached well within the longer run range suggests that some officials believe that low rates are necessary to ensure a smooth sustainable transition to pre-pandemic levels, not just to bring measurable metrics to target levels.

Now that inflationary pressures have strengthened, the tone has totally changed in markets. Everyone has been surprised by the upside on inflation, which triggered a massive sell-off since August all around the world. The UK’s two-year benchmark borrowing costs rose as high as 0.7 percent, up from just 0.1 percent only two months ago. Yields are rising even in the eurozone, which has a long track record of keeping inflation low. US Treasury Yields have more than doubled to 0.49 percent in less than a month as the market has fully priced in the projected rate rises.

In early 2021, central bankers were expected to tolerate accumulating inflationary pressures in order to allow the economy to come back to life, and approach pre-pandemic levels as early as possible. Now, securities markets are signaling concerns that central banks may overreact to surging prices and have to take corrective action in the future. Initially, these worries were most evident in the UK, where longer-term gauges of interest rate expectations, such as the three-year three-year forwards (the market’s best guess at where rates will be for three years, starting in three years’ time) have fallen below shorter-dated forwards for the first time since 2008. That means the market is effectively betting on a series of hikes followed by cuts as the economy slows rapidly and the BoE is forced to provide fresh stimulus, implying rapid rate rises by the BoE would be an error that might soon have to be undone.

A similar trend has now taken hold in the US bond market, as we begin to see 5-year, 5-year forwards beginning to catch up. This has generated further confusion for banks, who now do not know what to expect - and is a main driver for the diverging bets they are taking regarding the direction of interest rates.

Conclusion

As the main economic indicators suggest that the worst part of the crisis is now surpassed, the Fed is expected to announce the beginning of the tapering program this Wednesday. Such a decision will likely be followed by an increase in interest rates, which would finally allow banks to start investing their excess liquidity in the bond market. On the one hand, banks that had invested at lower rates will be hurt by a significant increase. Conversely, institutions that waited several months to invest their cash will benefit from such a decision. If the hike is substantial the former will suffer large losses as their bonds will become less attractive while the latter will gain. Only time will tell who benefited the most from the current uncertainty, those who were aggressive and took advantage of the opportunities presented by the market, or those who were more conservative in attempting to rapidly realign their strategy to the current recovery scenario.

Filippo Beni

Matteo Roberto Facta

Matteo Panizza

Sources:

Now that inflationary pressures have strengthened, the tone has totally changed in markets. Everyone has been surprised by the upside on inflation, which triggered a massive sell-off since August all around the world. The UK’s two-year benchmark borrowing costs rose as high as 0.7 percent, up from just 0.1 percent only two months ago. Yields are rising even in the eurozone, which has a long track record of keeping inflation low. US Treasury Yields have more than doubled to 0.49 percent in less than a month as the market has fully priced in the projected rate rises.

In early 2021, central bankers were expected to tolerate accumulating inflationary pressures in order to allow the economy to come back to life, and approach pre-pandemic levels as early as possible. Now, securities markets are signaling concerns that central banks may overreact to surging prices and have to take corrective action in the future. Initially, these worries were most evident in the UK, where longer-term gauges of interest rate expectations, such as the three-year three-year forwards (the market’s best guess at where rates will be for three years, starting in three years’ time) have fallen below shorter-dated forwards for the first time since 2008. That means the market is effectively betting on a series of hikes followed by cuts as the economy slows rapidly and the BoE is forced to provide fresh stimulus, implying rapid rate rises by the BoE would be an error that might soon have to be undone.

A similar trend has now taken hold in the US bond market, as we begin to see 5-year, 5-year forwards beginning to catch up. This has generated further confusion for banks, who now do not know what to expect - and is a main driver for the diverging bets they are taking regarding the direction of interest rates.

Conclusion

As the main economic indicators suggest that the worst part of the crisis is now surpassed, the Fed is expected to announce the beginning of the tapering program this Wednesday. Such a decision will likely be followed by an increase in interest rates, which would finally allow banks to start investing their excess liquidity in the bond market. On the one hand, banks that had invested at lower rates will be hurt by a significant increase. Conversely, institutions that waited several months to invest their cash will benefit from such a decision. If the hike is substantial the former will suffer large losses as their bonds will become less attractive while the latter will gain. Only time will tell who benefited the most from the current uncertainty, those who were aggressive and took advantage of the opportunities presented by the market, or those who were more conservative in attempting to rapidly realign their strategy to the current recovery scenario.

Filippo Beni

Matteo Roberto Facta

Matteo Panizza

Sources:

- FT

- Federal Reserve

- CNBC

- Kiplinger