Japan ‘s labor market could be defined as ‘chronically tight’. The life employment system is contributing to a lack of flexibility and inability to adapt to the fast-paced technological advancement that we are globally experiencing. In a job market where traditional employees systematically work extra hours and wages are not rising despite all the inflationary pressure, it is not surprising that people are becoming less risk-averse to seek higher returns. The recent development of Japan’s start-up market is the perfect opportunity in this sense: start-ups, now more than ever, are challenging the whole Japanese system, becoming a valuable employment option for young workers and threatening, even if not voluntarily, the large long-established corporations.

The Japanese labor market and the “lifetime” employee persona

Japan’s labor market’s trends and distinctive features are the direct consequence of the peculiar history and complex economic scenario of the country, delineating a unique situation in which historical, sociological and economic factors influence each other.

Since the COVID-19 period, the Japanese labor market has proven to be resilient, with limited fluctuations of the unemployment rate, which has stabilized at 2.60% in October and November after two months at 2.70%. But even with relatively stable rates, nowadays it is of common knowledge that Japan’s job market is undergoing a process of major change, among which the sharp decline in labor force is one of the most evident and discussed. Through population aging, Japan is experiencing the largest drop in number of workers among advanced economies, with projections of working-age population falling from its peak of 87 million in 1995 to about 55 million in 2050. In order to avoid a further undermining of potential growth of the economy, the government is implementing measures to simultaneously raise labor supply and productivity. The reforms focus on increasing labor participation rates for women, older people and foreigners. For example, with the introduction of the Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation and Advancement in the Workplace, since July 2022 firms with at least 301 regular employees are required to disclose gender pay gaps; while with the Act on Childcare Leave it has become possible for women (and men) to expand the maternity leave period.

Even if the working-age share of the population has been continuously decreasing, the number of people actually working has paradoxically increased: demographic decline has collided with an upswing in labor demand. This mix should have exercised high inflationary pressure on wages and on the economy in general: scarce workers usually demand higher compensation, which in turns makes firms charge higher prices to their customers. However, base salary has not increased, and this is attributable to various factors: first, the market has reacted by rising the supply of labor, rather than its price, also thanks to the above-mentioned laws in favor of minorities; second, labor unions have not fought for the cause, as it would have typically happen in other countries; finally, the growing number of part-time workers has contributed to drag down average pay gains.

Although heterogeneous, the major forces playing a role in the Japanese labor market are all symptoms of its tightness and lack of flexibility. These features are in turn embedded in the lifetime employment system, a phenomenon which has traditionally characterized Japan’s economy, under which employers refrain from firing workers and employees implicitly commit not to switch job until retirement. This approach has served the country well during the high-growth decades by facilitating the accumulation of specialized human capital and building trust between the employer and the so-called ‘salarymen’. The origins of this legendary figure, who works long hours in the office and heads back home late day after day, dedicating all their life to their job, are to be found in Japanese cultural inclination towards standardization and uniform. During the 1930s, white-collar employment dramatically accelerated in the country as a result of rapid militarization and government expansion. However, the catalyst for Japan’s modern emphasis on prioritizing working-life over private-life can be traced to the country’s need to boost the economy after the defeat in World War II, in order to be able to face the enormous burden of post-war reparations. From here the image of the salaryman as a ‘folk hero’ who serves his country by pouring all his energy into performing his corporate job.

But what about today? Who is the modern salaryman?

In the conventional sense, a salaryman is a loyal, white-collar employee of a big corporation, a middle-class office-worker engaged in traditional industries such as finance, commerce and business in general.

In Japanese culture, everyone has a role to fulfill, every person sooner or later joins one of the ‘building blocks’ of society; becoming a salaryman is seen as joining one of the most prestigious ‘blocks’. This is why parents carefully plan their children’s education, starting from preschool, so that they can be hired by traditional, big companies right after college to begin their lives as salarymen. Their routine is quite linear: wake up early in the morning, commute from their suburban neighborhoods to the city center to reach the workplace, work longer hours than they should, drink after work with their colleagues and go back home late in the night to repeat the same exact schedule the day after. The monotonous life of the ‘corporate zombies’ is just the result of three main indicative characteristics. First, group mentality: according to the Confucian idea of hierarchy, the leader is appointed as a ‘sacred’ figure, which determines lack of individualism for the employees, reluctance to change in the business and a yield to seniority. Second, high-social context: it stresses the importance of indirect communication both in the office and during the compulsory drinking sessions with the team after work (Nomikai Culture), which are seen as moments to build relationships with the sole aim of obtaining a faster promotion. Finally, working long hours with inadequate pay: from 7 to 8 official hours, most salarymen end up staying in the office for 10 to 13 hours a day, sometimes for 7 days a week, without being paid for overtime work. Labor Laws in this sense exist in Japan, they are just not enforced. One could wonder why people decide to work in these conditions for their whole lives, without exploring other opportunities. Japan’s labor productivity is the lowest amongst G-7 countries, implying that salarymen may not be motivated by a sense of ‘the greater good’ for the corporations or for their country. At the same time, statistics suggest that foreigners’ salaries in the same companies are higher on average, meaning that employers are perfectly conscious of the unusually low compensation of domestic workers. Therefore, the only plausible explanation is that, encouraged by the prestige of the role in Japanese culture, salarymen accept long working hours and low wages in exchange for job stability and future promotions in the company, with the hope of becoming executives and board members before retirement.

Nevertheless, nowadays the situation is changing. The figure of the salaryman is becoming a paradox: on one hand, traditional middle-class families, coming from at least two generations of salarymen, expect their sons to become one and those who reject this lifestyle are considered as failures; on the other hand, the expectation that salaried workers will dedicate their entire lives to their employers – even spending their free time socializing with coworkers – has inspired a series of derogatory nicknames among the youngest generations, including kigyou senshi (“corporate soldier”), and shachiku (“corporate livestock”). Gender issues have also risen to prominence in modern discussions, given that women have always been relegated to the role of ‘caretaker’ in the salarymen world.

But most importantly, thanks to the recent rise and development of the Japanese start-up market, today university students have a choice. They can increase their risk exposure, giving up the safety of lifetime employment to join a dynamic, less hierarchical reality where they have the chance to reach a key position in the company very rapidly, being able to gain a wider range of skills and make a real impact on a business where the returns, also in terms of salaries, are potentially much higher. And in a low-wage environment, after generations of scarcely paid overtime, this is a risk that most young Japanese are willing to take. Japan’s start-up ecosystem is currently able to draw top-tier talent to high-growth start-ups at a scale that was not possible fifteen years ago, determining one of the most significant developments in the Japanese economy since the end of the 1980s bubble and possibly radically changing, if not making obsolete, the salarymen culture as a whole.

Start-ups: distinguishing characteristics and how they can reshape working culture

Following the overview of the Japanese labour market, it is important to have an outlook on start-ups, their general characteristics, how they have changed working cultures, and what effects they have on productivity.

Start-ups are innovative, newly established businesses, usually with the objective to break into an industry. Their main characteristics are the following: The first and most important is the frequently used term “innovation”. Start-ups are almost always innovative in some way, whether it is about finding a gap in the market and filling it with a brand-new product, service, or business idea or coming up with something entirely new. They are also entrepreneurial, meaning that their visionary founder or founders take the initiative and try to turn their ideas into reality themselves, leading the start-up. Furthermore, the whole process of starting from only an idea and trying to establish an up-and-running business with extensive growth takes immense multiple-stage investments and involves extreme risks of failure. Most start-ups are out of business within the first five years.

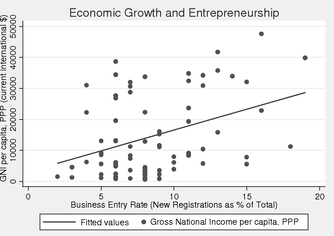

These very particular types of characteristics naturally entail a unique working culture. We all have this picture in our heads about an office with bean bags, Play Station, table football, etc. Even if it is somewhat of a stereotype, the working culture of the start-ups is really different than that of the traditional companies. The hierarchy is usually way flatter, and growth and uncertainty are constant, causing permanent change and requiring intense adaptability. Start-ups also have a two-way relationship with the economy. On one hand, the number and the role of start-ups within an economy can usually be a proxy for the development of the given economy. Ordinarily, there is a positive correlation between the proportional number of start-ups in an economy and its economic development.

On the other hand, even though start-ups usually represent a smaller proportion of companies within an economy, they have a wide range of significant effects on it. If successful, they can directly contribute to the growth of output and employment next to the probably even more important second-round effects. As mentioned earlier, they are crucial drivers of innovation, increasing the competitiveness, the productivity, and hence the growth of an economy, alongside the more minor but essential cultural effects they have on other companies.

Source: Semantic Scholar

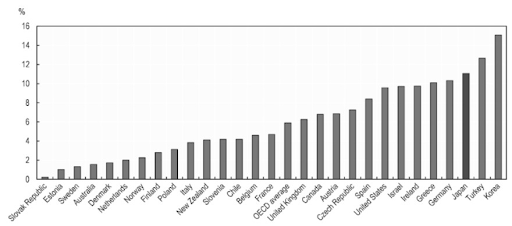

As it is shown in the graph above, the level of entrepreneurship in a given country has a significant positive effect on the level of economic growth in the same country, proving the previous statements. After discussing the Japanese labour market characteristics and general properties of the start-ups, the next step is to have a look at the start-up scene of Japan.

The rise of start-ups in Japan

Start-ups in Japan picked up slower than in many other developed or developing countries and there are a variety of reasons for that, both economic and cultural - these include the long-standing practice of lifetime employment, which leads to a lack of talent mobility, high costs associated with career changes due to tax policies, a conservative and failure-averse society, and limited avenues for start-up exits.

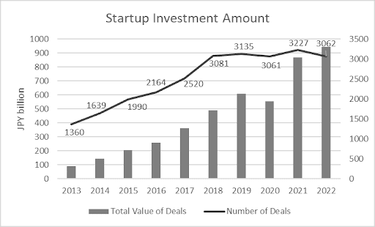

However, Japan’s start-up ecosystem seems to be gradually waking up and showing signs of increasing competitiveness. Plenty has changed in the last decade. The start-up investment amount in Japan has been growing at over 30% CAGR from 2013 to 2022. The number of deals doubled since 2013, but the investment amount grew tenfold, indicating the average amount per deal has grown approximately 5 times, providing start-ups with ample capital to tackle larger opportunities and build bigger businesses than before.

Source: Japan Startup Ecosystem Report

Unicorn start-ups: why they do not tell the correct story of the Japanese start-up phenomenon

According to CB Insights data of October 2023, with a total number of 7 unicorn start-ups, Japan has just 0.6% of the world’s 1230 start-ups of this kind. This figure has always been extremely low for Japan compared to other countries, such as the US that counts 661 unicorns or China with 172 as for October 2023. Furthermore, it is important to note that no unicorns were present in Japan until 2018. The first one of its kind was indeed Mercari, an e-commerce company that offers a marketplace for used items, which famously managed to become the first Japanese unicorn start-up in 2018. However, given the uniqueness of Japan’s market, this figure characterizing unicorns can be considered as misleading.

More specifically, it is worth noting that a newly-established company is labeled as a start-up as long as it is privately held and does not become a listed company. An exit through IPO strips off the company’s start-up and unicorn start-up status, regardless of the company’s valuation. To be considered a unicorn start-up, the company has to be privately held at the time of reaching a valuation of USD 1 billion or more.

Historically, Japanese start-ups have had a tendency to go public at relatively early stages. This is partly because the Tokyo Stock Exchange Growth Section, previously known as the Mothers Section, is more accommodating for earlier-stage IPOs compared to other stock exchanges globally. This unique aspect of the Japanese market has provided a distinctive opportunity for early liquidity, which is a notable benefit for companies. However, it has also contributed to a scarcity of unicorns and substantial private growth-stage funding rounds in Japan.

The aforementioned reasons lead to a case in which, unlike in many other countries, Japanese start-ups have more exits through an IPO than by M&A: the ratio of IPO vs. M&A exits stands indeed at around 8:2, compared to 3:7 in the US.

Between 2011 and 2021, 41 Japanese start-ups with a valuation of USD 1 billion or more experienced an exit by becoming listed on the stock market. While a valuation of that order through M&A would have given them unicorn status under different circumstances, the type of exit cannot be considered a measure of success or failure. As such, if we were to label the Japanese hidden gems of tech start-ups as unicorn start-ups, Japan would have been in the 4th place on the global unicorn standings, with 3.95% of the world’s unicorn start-ups being founded in the country.

What is bringing change to the situation of start-ups in Japan?

The government is one of the main forces driving the change of the Japanese start-up market, and therefore of the labor market as well. Japan’s Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida, views technological innovation and start-ups as the two key pillars of “new capitalism”. As such, he announced a five-year plan for Japanese start-ups in early 2022, with the goal of increasing their number and related investment amounts tenfold by 2027. Another confirmation of the government’s increasing interest in the start-up sector was given last summer, when the Cabinet created the position of start-up minister, who has the role to coordinate policies related to the matter.

In addition to its start-up-friendly policies, the Japanese government has also been deeply focused on technological innovation, particularly in the most-discussed areas of the last two years – Web3 and AI.

The stance of the government not only signals an increasing risk-taking appetite, but it is also driving a considerable increase in the number of Japanese start-ups.

As previously pointed out, Japan is traditionally known for being a very safe country. The economic growth over decades, combined with the traditional jobs-for-life employment system, seniority-based wage systems, and a strictly rules-based society, had kept uncertainties out of Japanese people’s lives to make them more risk-averse.

However, in the recent decades, a series of events has been gradually exposing the Japanese society to more uncertainties and risks. Firstly, the Lehman Brothers shock of September 2008 caused 940,000 job losses in only one year, and very soon after, the 2011 Tsunami had a similar impact on the Japanese people. While the recent COVID-19 pandemic is not a shock specific to Japan, it adds to the chain of destabilizing events.

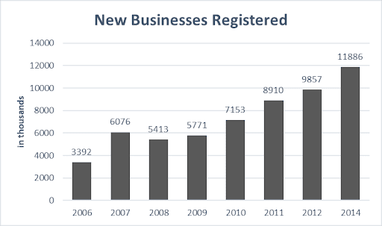

The increasing risk-taking appetite is evident in job-hopping among Japanese people, and more people are considering freelancing or even starting their own businesses. The following graph of the World Bank data indicates the trend of increase in new businesses and start-ups in Japan:

Source: EJable

Case Study: Money Forward

In order to better understand the development that the Japanese start-up environment is experiencing, the specific example of a notable start-up called Money Forward is useful to both illustrate the new dynamics of human capital mobility in Japan’s start-up ecosystem and to highlight the choices available to top university graduates who used to be funneled into large organizations’ lifetime employment arrangements.

Yosuke Tsuji, who founded Money Forward in 2012, joined Sony after graduating from Kyoto University. Tsuji was assigned to the accounting division where he found himself spending a great amount of time doing manual data entry. After three years, he had the opportunity to be seconded to Monex, a new securities company that was jointly funded by Sony and a Japanese entrepreneur, Matsumoto Oki.

Eventually, Tsuji completely transferred from Sony to Monex and a few years later, after obtaining his MBA from the Wharton School as part of the first cohort of Monex’s study abroad program, he founded the company Money Forward with Toshio Taki. Taki, a Keio University graduate, was getting his MBA from Stanford University, where he was sent by Nomura Securities, at the same time as Tsuji was at Wharton.

Tsuji’s experience highlights some significant ties between the traditional and emerging new logic of Japan’s start-up ecosystem. He joined a traditional company, Sony, and pursued a very traditional career path. However, he was seconded to a start-up, a typical practice for large Japanese firms who will “loan” their lifetime employees to subsidiaries or companies with close relations. This experience launched him into a new logic of Japan where elite, sharp, driven people were working to rapidly grow the start-up.

How the newly developed Japanese start-up phenomenon can reshape society, work culture and the nation as a whole

The changing landscape of the Japanese labor market, characterized by a significant increase in young professionals moving from large companies to start-ups, presents a multifaceted perspective for the country's work culture and economic performance. Although start-ups do not explicitly aim to challenge the existing labor market, their transformative influence, particularly in filling gaps within traditional structures, raises questions about potential disruptions and broader implications for Japan.

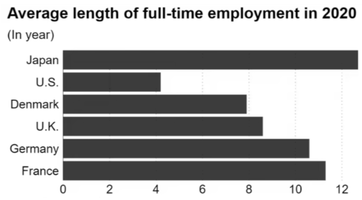

As previously discussed, the Japanese labor market was for many years characterized by a situation where people ready to work, including graduates from top universities, aimed to find a secure and stable job in which to build their career. For this reason, the country was, and still is, characterized by low turnover in companies and a much higher average duration of employment than other developed countries.

Source: Governments of countries, OECD

If the reader is wondering what are the reasons behind these data, the answer would certainly be the cultural environment, but it is worth mentioning that companies in Japan have created a system where workers are strongly incentivised to stay in their companies once having worked some years as their salary is strongly correlated with the level of seniority.

The following graph shows the expected wage growth moving from 10 to 20 years of tenure, for individuals aged 50s:

The following graph shows the expected wage growth moving from 10 to 20 years of tenure, for individuals aged 50s:

Source: OECD

However, the traditional labor market has a substantial problem: wages are not linked to productivity and the system is not expected to function well in an environment with an aging population, low productivity and slower growth.

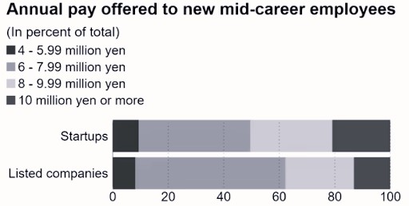

Start-ups are challenging precisely this aspect of Japanese working culture. In fact, they allow young and mid-career workers to earn higher salaries because they are more related to productivity than to seniority.

Start-ups are challenging precisely this aspect of Japanese working culture. In fact, they allow young and mid-career workers to earn higher salaries because they are more related to productivity than to seniority.

Source: En Japan

Start-ups contribute to an environment where the average duration of employment is shorter and workers are more risk-averse, as start-up jobs are generally less stable and secure than those of large companies. As previously pointed out, Japanese society is becoming less risk-averse and start-ups are certainly contributing to this process. The role of start-ups in Japan is increasing due to the changing work culture. For example, in the past, most students at top universities were willing to work at a big company, but now the situation is different. In fact, many start-up founders come from top universities, which indicates a change in the culture of graduates and employers.

For this reason, it is reasonable to think that the wave of start-ups is the consequence of a changing society, but not the source of change, although it may contribute to an acceleration of the process.

For this reason, it is reasonable to think that the wave of start-ups is the consequence of a changing society, but not the source of change, although it may contribute to an acceleration of the process.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Japanese labor market is undergoing a significant transformation which is also fostered by the rise of start-ups. The traditional image of the wage earner is being challenged as young workers seek alternatives in dynamic and innovative environments. The government's commitment to fostering the growth of start-ups reflects a broader societal shift towards the acceptance of risk and technological innovation. Although challenges persist, the evolving start-up landscape has the potential to help reshape Japan's work culture and economic performance, offering a more flexible and results-oriented alternative to traditional employment structures. The impact of startups on Japan's future is promising and could mark a crucial turning point in the country's economic and social dynamics.

By Chiara Evangelisti, Ginevra Ferraioli, Mihaly Schieszler, Emanuele Virno Lamberti

Sources

- Financial Times

- Business Insider

- Japandev

- IMF

- The Economist

- OECD

- Globis insights

- Japan Startup Ecosystem Report

- EJable

- Forbes

- Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

- Semantic Scholar

- OpenGrowth

- Carnegie

- Asia Nikkei

- ICLG