If you are not an English speaker by birth but studied the language, you probably know how easy it is to make mistakes. Pronunciation and syntax may not have been your best friends, especially under pressure, but usually small imperfections are forgivable. This is probably what the Lebanese finance minister Ali Hassan Khalil has been hoping for when he tried to ‘clarify’ one of his most unfortunate declaration.

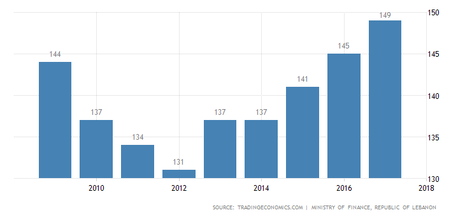

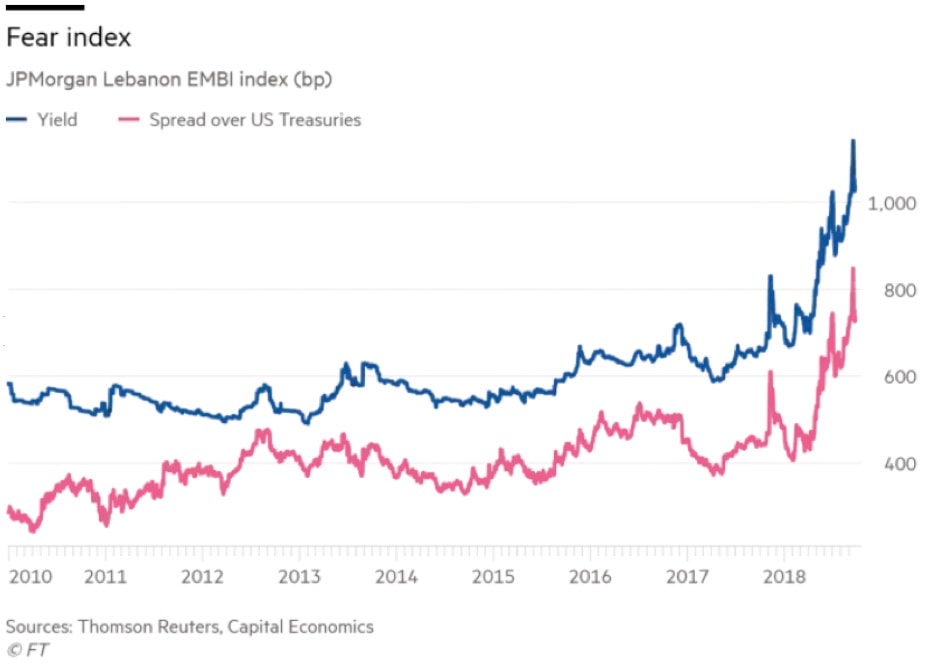

Lebanon has the fifth-highest public debt burden in the world, with a hardly sustainable 149% debt-to-GDP ratio, a figure that has been growing steadily for the last 19 years and refuses to slow down. Last month, Mr Ali told to a local newspaper that “It’s true that the ministry is preparing a plan for financial correction, including a restructuring of public debt”. But do you remember what your professor told you about the relationship between market confidence and interest rates in your undergrad economic classes? Right, poor confidence means high rates. And guess what: within one day Lebanese bonds fell to a record low. Mr Ali immediately tried to save the day clarifying that he meant “rescheduling” and not “restructuring”. After all, he also learnt English at public school.

Lebanon has the fifth-highest public debt burden in the world, with a hardly sustainable 149% debt-to-GDP ratio, a figure that has been growing steadily for the last 19 years and refuses to slow down. Last month, Mr Ali told to a local newspaper that “It’s true that the ministry is preparing a plan for financial correction, including a restructuring of public debt”. But do you remember what your professor told you about the relationship between market confidence and interest rates in your undergrad economic classes? Right, poor confidence means high rates. And guess what: within one day Lebanese bonds fell to a record low. Mr Ali immediately tried to save the day clarifying that he meant “rescheduling” and not “restructuring”. After all, he also learnt English at public school.

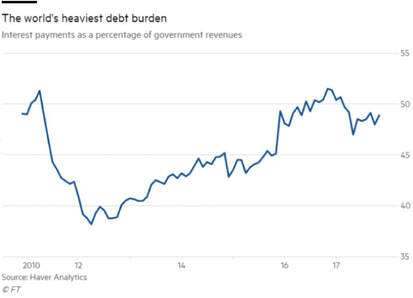

It is clear, however, that the question cannot be easily dismissed: trade deficit in Lebanon is impressive and the interest burden almost unbearable. But it is not all Mr Ali’s fault: the main problem of the country is a jammed political engine. After the last elections (held in May 6th, 2018) Lebanon does not have a government yet, and the parliament has been unable to approve a budget in twelve years (from 2005 to 2017). Many needed reforms await in political stall and the economy, without stimulus, is stagnating. A recent McKinsey report suggests that the country has its own resources to spend: the population is on average well educated and Lebanon could ‘export services or exploit tech industry’ to level off the trade deficit. Also, given the country’s strategic position, agriculture and tourism could flourish. However, none of this is going to happen unless the government builds the necessary infrastructures: Lebanon has a malfunctioning electricity web and one of the world’s worst internet connections.

Given the tragic political situation, it has been the responsibility of the national central bank to channel and drive the country’s economic policy. In order to protect the country’s peg with the dollar (which has remained fixed at 1.500 Lebanese pounds per dollar) the central bank has borrowed heavily from national commercial banks. To do so, however, the central bank has promised to pay high interests for the loans, which are now a heavy burden on taxpayers’ shoulders. It is clear that this practice must come to an end.

The future for the country’s finances is difficult to predict. The designated prime minister, Saad Hariri, is looking for new funds for Lebanon: he wants to stimulate the economy with public spending on infrastructure, much like the McKinsey report suggested. He has not secured any loans yet, but chances are good: Qatar promised to buy $500m worth of Lebanese bonds, and UAE declared that it will “support Lebanon all the way”. The prime minister has contacted China as well, which might be interested in investing in Lebanon given the fact that this latter will be key for China’s One Belt One Road project, and foreign donators pledged $11bn worth of loans during a conference in Paris. However, none of this will happen unless a government is formed.

Riccardo Ronzani