Two CEOs fired and reputations critically damaged, billions of Euros in criminal funds with connections to Russia laundered, and huge amounts of wealth destroyed. This describes the current outcome of one of the biggest money-laundering scandals in modern time.

Danske Bank is Denmark’s biggest bank, employing approximately 20000 people in its offices around Western Europe. Apart from the Nordic countries it also operates in the Baltics, Northern Ireland, and Ireland. Swedbank is a Swedish banking group, with a strong position in its home country, but also with significant operations in the Baltic countries; Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. During 2018 and 2019, both these institutions have been subject to immense pressure and great criticism after the further revelation of what has been called one of the biggest money-laundering scandals in modern time. Over €20 billion of funds stemming from criminal activity has allegedly flowed through and between the Estonian branches of Danske Bank and Swedbank, spanning the period between 20017 and 2016. Both banks have failed in the detection and termination of accounts and transactions that should raise big warning flags. It is a highly complex scheme that has been unraveled with the help of both external and internal whistleblowers, the Swedish and Danish press, law firms, and financial authorities in Denmark, Sweden and Estonia. This article aims to give an overview of how these events, step-by-step, were brought into the light.

Danske Bank

In September 2018, the Danish law firm Bruun & Hjejle publishes the results of the investigation had carried out, of leaked transaction records and account data of clients to Danske Bank’s Estonian operations. In the report they conclude that large amounts of money coming from Russian criminal sources have been siphoned through Danske’s branches in Estonia.

However, the problems started already in 2013, when an internal whistleblower from Danske Bank in Estonia sends an e-mail to the company board of directors and the internal audit division, claiming to know that the Estonian branch had failed in its money-laundering prevention and had continuing dealings with customers and accounts connected to Russian criminals and dirty money. This e-mail set in motion an internal revision, which subsequently confirmed the allegations made by the whistleblowing employee. The bank later moved to close all non-Estonian resident customer accounts in the Estonian branches.

In March 2017, the troubles continue. The Danish newspaper publishes an investigative article, claiming that Danske is involved in an international money laundering scheme, where millions of Euros from Russia have been transferred into the EU through Danske Bank and a few other institutions. The money can partially be traced back to the Putin family, the Russian FSB, and Azerbaijani government.

The Danish financial authorities conduct their own investigation, resulting in a report released in May 2018 deemed as a “horrifying read” by the press, in which they show that Danske has been covering up their problems in Estonia. The bank is also forced to increase their own capital, aimed at settling future fines. This investigation has far-reaching consequences: the Danish state prosecutor initiates an investigation, the Estonian authorities begin looking into the matter, and even the US authorities get involved since some of the suspected transactions may have been conducted in US dollars.

Thomas Borgen, Danske Bank’s CEO resigns on the 19th of September in 2018. Borgen himself was Danske’s head of the Estonian business during a major part of the period when the money laundering took place. Later, Danske Bank’s chairman also stepped down from his position.

Swedbank

During the process of bringing Danske’s shadier dealings into the light, other banks have been shown to be involved as well. One of the major players is Swedbank, the Swedish bank that also has substantial operations in the Baltics. Following a publication in the fall of 2018 by an external law firm who investigated Danske Bank’s businesses, the CEO of Swedbank, Birgitte Bonnesen, makes a public statement. She claims to be sure that Swedbank has no connection to any of the suspicious customers and transactions of Danske Bank’s Estonian branch that the law firm deems criminal. Bonnesen was between 2011 and 2014 the head of Swedbank’s Baltic operations. Even the Swedish financial authorities publicly defend Swedbank, claiming to have sufficient insight into the bank’s dealings through their task of monitoring Swedish banks’ anti-money laundering efforts.

In February 2019, the Swedish public TV channel SVT announces that they have been investigating information obtained through a leak. The leaked information consists of transaction records and account information, including transfers of funds of between accounts in the Estonian branches of Danske Bank and Swedbank.

Despite the assurances of the CEO, over 1000 customers that are prevalent in Danske Bank’s records also exist as customers of Swedbank. Funds have been moved through corporate and individual accounts, connected to companies and individuals based in tax havens about which insufficient information has been collected. Additionally, the investigation shows suspected laundering of close to €10 billion that Swedbank supposedly knew of since 2013.

Since the release of this information it has been discovered that Swedbank alerted selected shareholders of the report before it was made public, leading to the Swedish financial crime authorities initiating an investigation regarding possible insider trading matters. In March 2019 Swedbank also publishes the results of an internal follow-up investigation regarding their suspicious customers, but it is disregarded as flawed. A few days later, news break that the Swedish Financial crime authorities raided Swedbank’s headquarters, an action related to the insider trading allegations that has since developed into possible fraud as well. To further the blow, Swedbank may have lied to New York state financial authorities in 2018, when the bank denied having any customers related to another financial crime scandal, the Panama Papers. The US authorities announce that they are conducting an investigation into the matter.

On March 28th 2019, Birgitte Bonnesen is fired from her position, and on the annual general meeting the same day, shareholders deny her discharge of liability, exposing her to possible law suits.

Impact

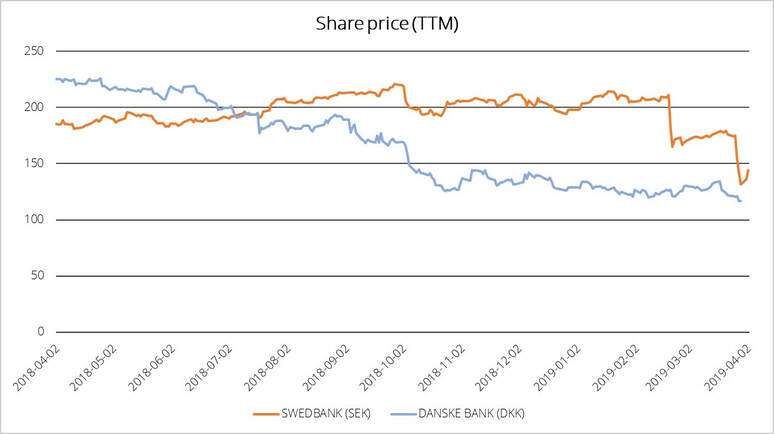

The consequences of these dealings are multi-faceted. Shareholders of both institutions has had a rough ride so far. Danske Bank’s share price has in the past year fallen from a high of 227 DKK to its current level of 124 DKK, corresponding to a 45% loss of value for shareholders. Swedbanks share has made a similar journey, albeit in a shorter time frame. Peaking at 221 SEK in September 2018, the Swedbank share is currently trading at 145 SEK, showing a decrease in value of 35%. This is a big financial blow to the shareholders, but the banks’ have also lost another thing that is valuable in the business world; reputation. There are divided opinions on whether a damaged reputation will have a long-term impact, but it does have a negative effect in the short-term.

Danske Bank is Denmark’s biggest bank, employing approximately 20000 people in its offices around Western Europe. Apart from the Nordic countries it also operates in the Baltics, Northern Ireland, and Ireland. Swedbank is a Swedish banking group, with a strong position in its home country, but also with significant operations in the Baltic countries; Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. During 2018 and 2019, both these institutions have been subject to immense pressure and great criticism after the further revelation of what has been called one of the biggest money-laundering scandals in modern time. Over €20 billion of funds stemming from criminal activity has allegedly flowed through and between the Estonian branches of Danske Bank and Swedbank, spanning the period between 20017 and 2016. Both banks have failed in the detection and termination of accounts and transactions that should raise big warning flags. It is a highly complex scheme that has been unraveled with the help of both external and internal whistleblowers, the Swedish and Danish press, law firms, and financial authorities in Denmark, Sweden and Estonia. This article aims to give an overview of how these events, step-by-step, were brought into the light.

Danske Bank

In September 2018, the Danish law firm Bruun & Hjejle publishes the results of the investigation had carried out, of leaked transaction records and account data of clients to Danske Bank’s Estonian operations. In the report they conclude that large amounts of money coming from Russian criminal sources have been siphoned through Danske’s branches in Estonia.

However, the problems started already in 2013, when an internal whistleblower from Danske Bank in Estonia sends an e-mail to the company board of directors and the internal audit division, claiming to know that the Estonian branch had failed in its money-laundering prevention and had continuing dealings with customers and accounts connected to Russian criminals and dirty money. This e-mail set in motion an internal revision, which subsequently confirmed the allegations made by the whistleblowing employee. The bank later moved to close all non-Estonian resident customer accounts in the Estonian branches.

In March 2017, the troubles continue. The Danish newspaper publishes an investigative article, claiming that Danske is involved in an international money laundering scheme, where millions of Euros from Russia have been transferred into the EU through Danske Bank and a few other institutions. The money can partially be traced back to the Putin family, the Russian FSB, and Azerbaijani government.

The Danish financial authorities conduct their own investigation, resulting in a report released in May 2018 deemed as a “horrifying read” by the press, in which they show that Danske has been covering up their problems in Estonia. The bank is also forced to increase their own capital, aimed at settling future fines. This investigation has far-reaching consequences: the Danish state prosecutor initiates an investigation, the Estonian authorities begin looking into the matter, and even the US authorities get involved since some of the suspected transactions may have been conducted in US dollars.

Thomas Borgen, Danske Bank’s CEO resigns on the 19th of September in 2018. Borgen himself was Danske’s head of the Estonian business during a major part of the period when the money laundering took place. Later, Danske Bank’s chairman also stepped down from his position.

Swedbank

During the process of bringing Danske’s shadier dealings into the light, other banks have been shown to be involved as well. One of the major players is Swedbank, the Swedish bank that also has substantial operations in the Baltics. Following a publication in the fall of 2018 by an external law firm who investigated Danske Bank’s businesses, the CEO of Swedbank, Birgitte Bonnesen, makes a public statement. She claims to be sure that Swedbank has no connection to any of the suspicious customers and transactions of Danske Bank’s Estonian branch that the law firm deems criminal. Bonnesen was between 2011 and 2014 the head of Swedbank’s Baltic operations. Even the Swedish financial authorities publicly defend Swedbank, claiming to have sufficient insight into the bank’s dealings through their task of monitoring Swedish banks’ anti-money laundering efforts.

In February 2019, the Swedish public TV channel SVT announces that they have been investigating information obtained through a leak. The leaked information consists of transaction records and account information, including transfers of funds of between accounts in the Estonian branches of Danske Bank and Swedbank.

Despite the assurances of the CEO, over 1000 customers that are prevalent in Danske Bank’s records also exist as customers of Swedbank. Funds have been moved through corporate and individual accounts, connected to companies and individuals based in tax havens about which insufficient information has been collected. Additionally, the investigation shows suspected laundering of close to €10 billion that Swedbank supposedly knew of since 2013.

Since the release of this information it has been discovered that Swedbank alerted selected shareholders of the report before it was made public, leading to the Swedish financial crime authorities initiating an investigation regarding possible insider trading matters. In March 2019 Swedbank also publishes the results of an internal follow-up investigation regarding their suspicious customers, but it is disregarded as flawed. A few days later, news break that the Swedish Financial crime authorities raided Swedbank’s headquarters, an action related to the insider trading allegations that has since developed into possible fraud as well. To further the blow, Swedbank may have lied to New York state financial authorities in 2018, when the bank denied having any customers related to another financial crime scandal, the Panama Papers. The US authorities announce that they are conducting an investigation into the matter.

On March 28th 2019, Birgitte Bonnesen is fired from her position, and on the annual general meeting the same day, shareholders deny her discharge of liability, exposing her to possible law suits.

Impact

The consequences of these dealings are multi-faceted. Shareholders of both institutions has had a rough ride so far. Danske Bank’s share price has in the past year fallen from a high of 227 DKK to its current level of 124 DKK, corresponding to a 45% loss of value for shareholders. Swedbanks share has made a similar journey, albeit in a shorter time frame. Peaking at 221 SEK in September 2018, the Swedbank share is currently trading at 145 SEK, showing a decrease in value of 35%. This is a big financial blow to the shareholders, but the banks’ have also lost another thing that is valuable in the business world; reputation. There are divided opinions on whether a damaged reputation will have a long-term impact, but it does have a negative effect in the short-term.

Another thing to consider is that the banks will not be able to put these matters behind them in the near time. There are ongoing investigations, and both Danske and Swedbank are facing potential fines from their own governments but also from the US. If the US financial authorities find that any of these transactions have been denominated in US dollars, there is a big chance that they will significantly restrict the institutions’ abilities to continue dealing in dollars which could be a critical hit.

To summarize, this scandal will continue to be held over the banks’ literal heads for the foreseeable future. The new CEO’s of both institutions will be taking over damaged ships and will have to use all their skill and perseverance to remedy the lost reputation in the eyes of shareholders and supervisors. There is also a big possibility that even more institutions will be discovered as contributors, only time will tell.

Tobias Mattsson

To summarize, this scandal will continue to be held over the banks’ literal heads for the foreseeable future. The new CEO’s of both institutions will be taking over damaged ships and will have to use all their skill and perseverance to remedy the lost reputation in the eyes of shareholders and supervisors. There is also a big possibility that even more institutions will be discovered as contributors, only time will tell.

Tobias Mattsson